Jean-Luc Godard was one of the most prolific filmmakers of the early 1960s, producing a string of exciting, creative films that, as Susan Sontag once wrote, work as one long piece of cinema, an evolving, ever-expanding movie from a singular artistic source. Of those early movies, one of the least talked about seems to be Une Femme Mariée (A Married Woman), his 1964 study of one woman's emotional dilemma. Perhaps it's just that the movie fell between the more popular Band of Outsiders [review] and the sci-fi detective film Alphaville [review], and so the less flashy feature got lost behind the spotlight. Regardless, it's an unfair development. A Married Woman is a worthy companion piece to Godard's divisive 1963 masterpiece, Contempt [review], exploring many of the same themes of infidelity, changing affections, and performance, but this time more sympathetic to the female side of the story.

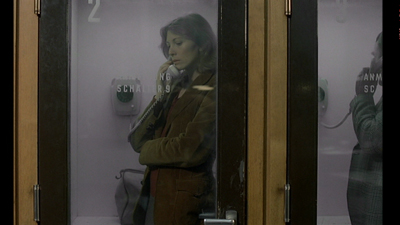

Macha Méril stars as Charlotte, a young wife married to Pierre (Philippe Leroy), an older man whose previous marriage ended after two months, leaving him a cuckold with a young son. Despite going through the motions of wife and lover, Charlotte has grown tired of the arrangement, and she has sought extramarital passions in the arms of a handsome actor, Robert (Bernard Noël). Robert wants her to leave Pierre and be with him, and Charlotte has agreed to get a divorce so they can make that happen. Yet, pulling the trigger is not so easy.

A Married Woman is told in a series of distinct chapters, opening with a rendezvous with Robert, transitioning into Charlotte's return to family and time with Pierre, then a little girl talk, and finally back to Robert. Far from a conventional narrative, A Married Woman is composed of Godard's usual aesthetic, like a series of cut-up snapshots rearranged and pasted together. The final product is a little like a parlor-room drama given a modern remix. Continuing his groundbreaking experiments with music, advertising, and slogans, Godard splices conversations with movie posters (as well as his usual self-reflexive references to the same), ads for brassieres, and the sights of Paris, including the Eiffel Tower and a Jean Cocteau window display. Instead of the usual talking heads, he presents conversations as one-sided, having each character look directly into the camera and state their business, with their partner sometimes posing questions off-screen. Thus, discussions are more like filmed interrogations than an exchange of information, each lover demanding to know if they are loved and how much. Just what are you prepared to do for me?

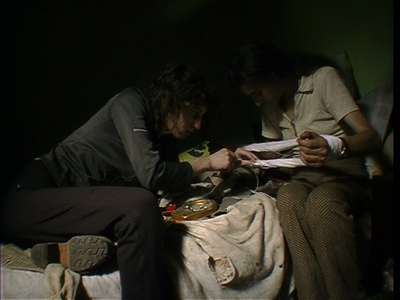

Ever the trickster, Godard plays fast and loose with the idea of the male gaze in A Married Woman. The lovemaking scenes are staged using strictly framed shots, focusing on different parts of Charlotte--the back of her neck, her bellybutton, her legs. It is both reverential and objectifying, loving and lustful, a dichotomy Godard is acknowledging as existing in both of Charlotte's male partners. As she will figure out, they want to possess the parts, but not necessarily the whole. She wonders why both of them don't want to see her in her complete nakedness, Robert even imploring her to put on a shirt as she wanders their shared boudoir in panties and nothing more--though even in her exhibitionism, she hides a little, covering her breasts with her arm. Then again, if Robert would express his desire to see them, she'd reveal all. Interesting, too, that both the husband and boyfriend end sexual encounters with talk of pregnancy, of each wanting to give Charlotte a baby. Her nervous reluctance is refreshing. Not all modern women want to be mothers, after all, and the implication is that the men see this as a final stamp of ownership, the way to shackle her. The men are frighteningly interchangeable, especially the way Godard regularly shoots only the backs of their heads or leaves them off camera entirely.

Marriage didn't go so well for Pierre the first time, something that comes to bear in his new relationship, and Godard is sharply aware of the double-standards that come to play in a male/female relationship, especially in regard to sexual freedom. Charlotte says as much when Pierre questions her past history, and she knows he doesn't trust her because of his own history. As a pilot, Pierre is often gone, and in his absence, he once had a private detective follow Charlotte, catching her in her early flirtation with "that actor." As she tells him, even if his suspicions are correct, it doesn't give him the right to have her tailed.

Godard is smart to have Charlotte be such a conflicted character and not altogether wholesome. She is often childish, fighting over whether she can play some records or worrying about her bust size. The auteur is fascinated by the division between youth and age as much as he is the division of gender. There are ongoing discussions of memory vs. action, past vs. present. Pierre is hopelessly stuck in the past, whereas Charlotte only cares about right now. In one of his usual extreme juxtapositions, Godard introduces us to Pierre just as he is returning from having been to Auschwitz to watch the trials of Nazi war criminals, all of whom profess to not being able to remember the atrocities. Is Charlotte's disinterest evidence of a flighty personality, or is Pierre merely an intellectual poser? In the middle is Pierre's guest (director Roger Leenhardt playing himself), an even older man who is more in tune with where these things intersect. Intelligence, as he says, is the ability to compromise, to be able to assess all factors and proceed accordingly.

Ultimately, this is what Charlotte must do, particularly after a mid-point twist where she realizes she is pregnant and has no idea which of the two possible candidates is the father. Macha Méril is wonderful to watch in the movie, making Charlotte more than an empty vessel for Godard's philosophy--even if her discussions of acting with Robert bring to mind some of the theories of Robert Bresson, who saw actors as models to be posed. (A brilliantly choreographed meeting between the lovers, showing the lengths they'll go to cover their tracks, also reminded me of Bresson. Specifically, the scenes of thievery in Pickpocket.) As an actress, Méril is always aware of both her surroundings and the internal debate that Charlotte is having. She always appears to be thinking, she is never blank. Her performance serves Godard's subversion of the male gaze quite well, actually, and Raoul Coutard's gorgeous photography practically dares you to get lost in her beauty and forget that there is a brain in her head. Good luck, because Méril makes it pretty much impossible.

The tragedy of A Married Woman, then, is that for as much as Charlotte may want to weigh her options, what she discovers in her final tryst with Robert is that the choice is ultimately out of her hands. Any relationship lives or dies on the vagaries of its participants, and so as much as Pierre's mistrust of her is a self-fulfilling prophecy, so too is Robert's status as an actor and his role as the other man going to make him a capricious lover, someone for whom permanence is not truly viable. As in life, the end of the film is abrupt, coming before Charlotte--or the viewer--is ready, and thus hitting all the harder.