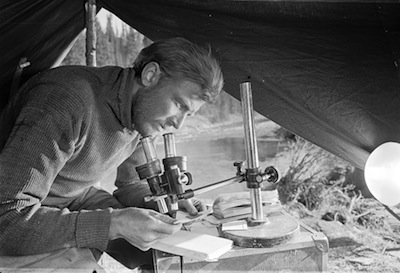

An expedition of four enters the Siberian wilderness. Scientific tests of the soil in the area have shown a possibility for diamond deposits. The group consists of three geologists and their guide, all veterans of similar hunts, though yet to experience success. The mission to find the diamonds could bring them great glory; if they are successful, the treasure will fund new Soviet endeavors. If they fail, it's uncertain if they will get another chance or if new explorers will be sent in their stead.

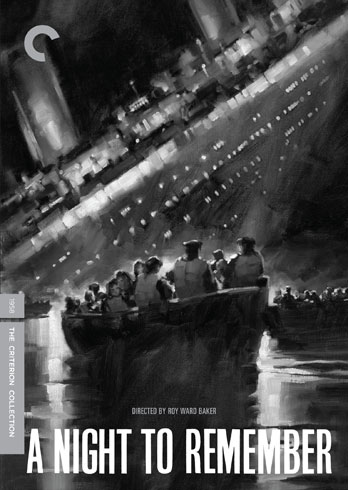

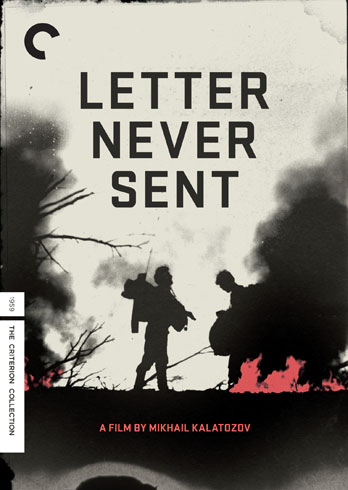

This is the premise for

Letter Never Sent, Russian filmmaker Mikhail Kalatozov's 1959 backwoods drama. It's a man vs. nature tale worthy of Werner Herzog, one with hubris, misplaced ambition, and even a touch of romance.

Letter Never Sent is both human and elemental.

Sabinin (Innokenti Smoktunovsky) leads the search party. He is a level-headed man, and his ongoing missive to his wife (Galina Kozhakina) gives the film its title. He began the letter on the plane, but instead of sending it back with the flight crew, he hangs onto it, turning it into a record of their endeavors. The pair of geologists on his team is in a relationship. Andrei (Vasili Livanov) is smart and affectionate, and he and Tanya (Tatyana Samoilova, also in Kalatozov's

The Cranes are Flying [

review]) share a common pursuit. The guide for the trip, Sergei (Yevgeny Urbansky), also has feelings for Tanya. He is physical and earthy. He is not necessarily Andrei's better, but he is the man's opposite. One is analytical, the other instinctual.

This set-up creates a strong dynamic. All the players have their function, and they serve them. Tanya is aware of Sergei's intentions, as is Sabinin, who acts as a calming influence. Whether Andrei has any clue is up to interpretation. He and Sergei have an altercation that ends ambiguously. It may be telling, however, that Tanya discovers the evidence they have been seeking after dismissing Sergei, and its Andrei that she first celebrates with. Yet, each man has a redemptive moment on the horizon, a chance to take action and make a sacrifice.

It's after Tanya's finding that the real movie begins, and

Letter Never Sent turns into a story of survival rather than one of discovery. The morning after she digs up the diamond, the team awakens to a forest ablaze. It's as if Mother Earth is rising up to stop them. She can't simply let these men tear into her soil and take her prize. The hunting party must grab what they can and make a run for safety. Before they find it, they will contend with not just fire, but rain and snow, as well. The terrain is unforgiving, and the weather unrelenting.

Letter Never Sent is a wondrous thing to witness unfold. Mikhail Kalatozov, who is perhaps best known for his innovative travelogue

I Am Cuba [

review], has a remarkable sense of framing and a masterful photographic eye. He and his regular cinematographer Sergei Urusevsky possess an uncanny grasp of black-and-white dynamics. The nature photography in

Letter Never Sent is beautiful, with the camera acting as a vibrant observer. Kalatozov moves with and around the actors, dodging tree branches, going underneath and above the performers, and often acting in concert with them. Though a cold observer, the camera additionally serves as a unifying tool, connecting what the geologists are doing with the environment they are doing it in. In the early scenes, Kalatozov employs montage to show their tireless hunt while laying flickering flames over the top of their activities. As it is occurring, it appears the fire is meant to symbolize the passion with which they undertake their duties; as we get deeper in, these conflagrations are revealed to have been foreshadowing.

Kalatozov's direction manages to be both poetic and realistic, striking an intentional balance between artistic expression and the truth of his scenario, the virtuosity of the invented visuals and the actual beauty of the Siberian forests. This illustrates the disparity between man's dreams of glory and the harsh reality of the natural world. The obvious flourishes of

Letter Never Sent's first act disappear once the fire comes for real. From there, the only fantasies Kalatozov indulges are Sabinin's delusions. He converses with his wife, and he sees the industry he believes their findings will make possible. Yet, neither is really happening.

Which isn't to say that all the beauty vanishes once the trees start to burn. Nature has the same capacity to nourish as it does to destroy. The cleansing rain creates salvation, and Kalatozov and Urusevsky capture the relief in a way that resembles religious ecstasy. Tanya leans against a tree and lets the water pour over her, and her expression is serene and joyous. The irony, of course, is that the same rain will turn to ice and become their next deadly obstacle. Time and space become immaterial, with seasons seemingly passing overnight and civilization appearing no nearer.

Letter Never Sent is a test of wills: do these explorers have what it takes to get home? Can Sabinin deliver his message, or is failure and hopelessness all that really waits for those who dare challenge that which is bigger than all of us?

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVD Talk.

Please Note: The images used here are from promotional materials, not from the Blu-Ray.