A round-up of my reviews for non-Criterion movies in the past month.

IN THEATRES...

* The Conspirator, Robert Redford has some questions about Lincoln's assassination. Asked and answered!

* Hanna, the feisty action picture starring a young female lead to see right now.

* Meek's Cutoff, Michelle Williams and fellow pioneers get lost on the Oregon Trail. So lost, they end up someplace where it's not even raining. Directed by Kelly Reichardt.

* Miral, Julian Schnabel's fascinating yet muddled look at the history of a string of Palestinian women in Israel in the latter half of the 20th Century. Starring Freida Pinto.

* Stake Land, a derivative but totally entertaining vampire-killing road trip.

* Super, in which James Gunn takes on the whole "real world crimefighter" thing, and his hero gets upstaged by a little girl.

* Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, Apichatpong Weerase-thakul's divisive meditation on death, folklore, and horny fish.

* Your Highness: Oooh! Oooh! I got one. "Puff, puff, pass--emphasis on the pass."

In addition to my regular movie reviews, check out my contribution to the Portland Mercury, in which I pick a few movies to go along with the a recent week-long booking of Full Metal Jacket. (Longer reviews of two of the movies mentioned: The Strange One and Paths of Glory.)

ON DVD/BD...

* A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Spielberg meets Kubrick, and the results are stunning.

* Arabeseque, Stanley Donen tries to recapture the magic of his previous success and fails. With Gregory Peck and Sophia Loren.

* The Incredibles, Pixar's killer superhero adventure gets the Blu-Ray treatment.

* Ingrid Bergman in Sweden, three films from the homeland, before the iconic actress went to Hollywood.

* Leaving, an absolutely ordinary, and thus boring, infidelity drama with Kristin Scott Thomas.

* No One Knows About Persian Cats, noble in its ambitions, not quite as successful in its final execution, a rock 'n' roll movie from Iran and Bahman Ghobadi.

* The Paranoids, a quirky dramedy from Argentina. An intriguing character study made all the better by its awesome lead actor.

* The Perfume of the Lady in Black, a chilly, pretty entry in the "blonde woman goes mad" genre of psychological horror. From 1974.

* Ricky, Francois Ozon's version of a family movie. Those crazy French! (Also, check out my capsule review of his most recent film, Potiche.)

* The Scent of Green Papaya, the perennial art house film from the early '90s is gorgeous on Blu-Ray. A romantic cinematic poem.

* Summer in Genoa, a movie from Michael Winterbottom, starring Colin Firth as a widower father trying to lead his family back to normalcy.

* The Vanquished, an early triptych by Michelangelo Antonioni.

Saturday, April 30, 2011

Friday, April 29, 2011

FEAR AND LOATHING IN LAS VEGAS (Blu-Ray) - #175

"Ignore the nightmare in the bathroom." - Raoul Duke (surely, if not an old proverb already, it will be eventually).

True story: half an hour after watching Terry Gilliam's 1998 adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas this morning, I was walking down my street. As I passed a house where some contractors were working on a remodel, I overheard one of the contractors explaining to the other about the "Paul is Dead" conspiracy surrounding the Abbey Road album cover. "George was dressed as a gravedigger," he said, "and Paul wasn't wearing any shoes."

Clearly something is in the ether today. The Beatles released Abbey Road, the last album they recorded, in late 1969. Within a year, they were no more, arguably closing the door on 1960s pop culture, following the zeitgeist of the decade right down the tubes. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is set in 1971. The peace-and-love generation is long gone, and chaos only exists in its place. Hunter S. Thompson's story of tumbling into a drug-fueled rabbit hole of decadence and danger was a harbinger of the decade that was to follow. Like the dust cloud at the motorcycle race he is sent to Sin City to cover, the 1970s would be a brown maelstrom of disappointment and disaster. Political activism would give way to complacency post-Nixon, and music and fashion was becoming bloated and boring. Let's face it, if it weren't for its cinema, the 1970s would be a decade best left forgotten. Torch the records, send it away!

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was long considered an "unfilmmable" book. Like William S. Burroughs' Naked Lunch, it was a tome revered for the irreverent prose style and the author's willingness to engage with all things taboo, and without the quality of the former the latter was rather difficult to capture. Conventional narratives these are not, and it would take equally unconventional filmmakers to make a movie out of them. Luckily, David Cronenberg got his mitts on Naked Lunch [review], and Terry Gilliam, the former Python turned surreal fantasist, tackled Fear and Loathing.

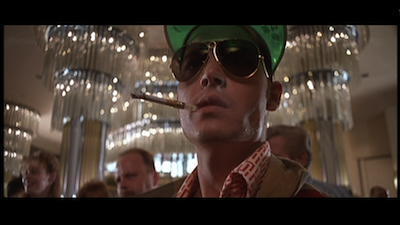

Johnny Depp stars as Hunter S. Thompson, who went to Las Vegas as a journalist, covering an epic motorcycle race in the desert under the guise of Raoul Duke. He would also stick around to report on a convention for law enforcement officers. Ironically, their chosen subject was stopping narcotics. Thompson is a notorious druggy, and he spends the entirety of this movie hopped up on some chemical concoction or another. Along for the ride is his "attorney," the larger-than-life Dr. Gonzo, played with pure animalistic chutzpah by Benicio Del Toro. The actor gives a purely physical performance, ditching actorly mannerisms for phlegm and sweat. He is perpetually clearing himself of some sort of bodily substance, and his character has a sinister bend that is truly disturbing. By juxtaposition, Thompson is a cartoon character, and Depp plays him as such. As a performance, it is definitely one extended impression of the real deal, but Depp approaches Thompson's contrived personage with the same honest intensity as, say, Robert Downey Jr. taking on Charlie Chaplin [review]. It's less an act than it is sculpture: the karate chops and whistles chip away at the artifice until it turns into something absolutely authentic.

Plot seems irrelevant in a discussion of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The movie's script went through various permutations, including a pass by Repo Man -director Alex Cox, who is one of four credited screenwriters (Gilliam is also on the list). Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas doesn't really have a narrative arc, it's more like a narrative descent. The thrust of the story is ever downward, as each over indulgence alienates Gonzo and Thompson further from real life, to a point where things get so paranoid and weird, not even the criminal underbelly of Vegas will have anything to do with them. There is a tremendous scene here in a back-alley diner, featuring a memorable cameo by Ellen Barkin. She plays a waitress who ends up on the wrong side of Gonzo's anger, and Del Toro's beastly delivery of the threats is so convincing, it's hard to tell if Barkin is acting or if she's really scared.

-director Alex Cox, who is one of four credited screenwriters (Gilliam is also on the list). Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas doesn't really have a narrative arc, it's more like a narrative descent. The thrust of the story is ever downward, as each over indulgence alienates Gonzo and Thompson further from real life, to a point where things get so paranoid and weird, not even the criminal underbelly of Vegas will have anything to do with them. There is a tremendous scene here in a back-alley diner, featuring a memorable cameo by Ellen Barkin. She plays a waitress who ends up on the wrong side of Gonzo's anger, and Del Toro's beastly delivery of the threats is so convincing, it's hard to tell if Barkin is acting or if she's really scared.

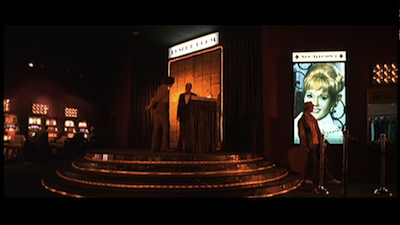

It's an interesting view of Las Vegas, taking us down its glitzy ladder rung by rung, going from its most surreal heights (a version of the kiddy casino Circus Circus) to this rundown, all-too-earthly greasy spoon. It seems to me that the key to the material is in understanding that the city itself is a trippy place, that the drugs are almost a tool for comprehending its garishness. No matter how weird the hallucinations get, Vegas can match the nightmare horror for horror. Visually, Gilliam and his team make tremendous use of the city's neon landscape. A driving montage down the strip uses rear projection and cutaways to melt and bend the surrounding signs and advertisements. Overdone hotel wallpaper and carpets come alive and swallow the patrons. Cinematographer Nicola Pecorini (The Order , The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus [review]) often sets the camera at an angle, so that the image leans to one-side, upsetting the equilibrium of the frame. It's almost as if the movie is trying to spill its protagonists out of the other side of the screen the way you or I might try to kick away a dog humping our leg.

, The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus [review]) often sets the camera at an angle, so that the image leans to one-side, upsetting the equilibrium of the frame. It's almost as if the movie is trying to spill its protagonists out of the other side of the screen the way you or I might try to kick away a dog humping our leg.

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is nearly formless in its construction, though it solidifies over each selective viewing. To carry the drug metaphor, you build a kind of tolerance, gaining an ability to maintain the more you partake. Though I wouldn't have said so when it was first released, I'd hazard to call it Terry Gilliam's most together movie. Not necessarily his best, but possibly the one where he is most in command of the elements. For all the bedlam depicted onscreen, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is meticulously choreographed. Many of the scenes of Gonzo and Thompson wandering through the casinos while going off their heads play for extended lengths without much cutting. In these, they are each performing independent actions, including interacting with crowds of extras. Sometimes it's super complicated, like the hotel bar when they first get to town, just before all the other drinkers turn into lizards; other times, it's more simple. When Gonzo argues their way into a Debbie Reynolds concert, Thompson stays by himself, doing more drugs on the sly. Gilliam keeps the shot wide and lets the actors move around the frame. You could watch either of them do their thing, they are both doing something interesting, and yet it also works perfectly in tandem.

Naturally, with an experience like Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, there is no real exit, no grand conclusion to be had. The trip ends--in both senses of the word. The vacation is over, the vacationers have to come down off of the high. Yet, Gilliam gives us a satisfying wrap-up anyway. In his way, he has contained the chaos, and so there is a relief in making our way back out of it. Rubber hits the road, and Hunter S. Thompson heads back to Los Angeles, a smile on his face, remembering all the devils in the preceding details, having survived to return to some kind of perceived normalcy. And yet, that grin also says it's never going to be completely over: the craziest diamonds always shine on.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Screen captures are from the DVD, not the Blu-Ray.

True story: half an hour after watching Terry Gilliam's 1998 adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas this morning, I was walking down my street. As I passed a house where some contractors were working on a remodel, I overheard one of the contractors explaining to the other about the "Paul is Dead" conspiracy surrounding the Abbey Road album cover. "George was dressed as a gravedigger," he said, "and Paul wasn't wearing any shoes."

Clearly something is in the ether today. The Beatles released Abbey Road, the last album they recorded, in late 1969. Within a year, they were no more, arguably closing the door on 1960s pop culture, following the zeitgeist of the decade right down the tubes. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is set in 1971. The peace-and-love generation is long gone, and chaos only exists in its place. Hunter S. Thompson's story of tumbling into a drug-fueled rabbit hole of decadence and danger was a harbinger of the decade that was to follow. Like the dust cloud at the motorcycle race he is sent to Sin City to cover, the 1970s would be a brown maelstrom of disappointment and disaster. Political activism would give way to complacency post-Nixon, and music and fashion was becoming bloated and boring. Let's face it, if it weren't for its cinema, the 1970s would be a decade best left forgotten. Torch the records, send it away!

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was long considered an "unfilmmable" book. Like William S. Burroughs' Naked Lunch, it was a tome revered for the irreverent prose style and the author's willingness to engage with all things taboo, and without the quality of the former the latter was rather difficult to capture. Conventional narratives these are not, and it would take equally unconventional filmmakers to make a movie out of them. Luckily, David Cronenberg got his mitts on Naked Lunch [review], and Terry Gilliam, the former Python turned surreal fantasist, tackled Fear and Loathing.

Johnny Depp stars as Hunter S. Thompson, who went to Las Vegas as a journalist, covering an epic motorcycle race in the desert under the guise of Raoul Duke. He would also stick around to report on a convention for law enforcement officers. Ironically, their chosen subject was stopping narcotics. Thompson is a notorious druggy, and he spends the entirety of this movie hopped up on some chemical concoction or another. Along for the ride is his "attorney," the larger-than-life Dr. Gonzo, played with pure animalistic chutzpah by Benicio Del Toro. The actor gives a purely physical performance, ditching actorly mannerisms for phlegm and sweat. He is perpetually clearing himself of some sort of bodily substance, and his character has a sinister bend that is truly disturbing. By juxtaposition, Thompson is a cartoon character, and Depp plays him as such. As a performance, it is definitely one extended impression of the real deal, but Depp approaches Thompson's contrived personage with the same honest intensity as, say, Robert Downey Jr. taking on Charlie Chaplin [review]. It's less an act than it is sculpture: the karate chops and whistles chip away at the artifice until it turns into something absolutely authentic.

Plot seems irrelevant in a discussion of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The movie's script went through various permutations, including a pass by Repo Man

It's an interesting view of Las Vegas, taking us down its glitzy ladder rung by rung, going from its most surreal heights (a version of the kiddy casino Circus Circus) to this rundown, all-too-earthly greasy spoon. It seems to me that the key to the material is in understanding that the city itself is a trippy place, that the drugs are almost a tool for comprehending its garishness. No matter how weird the hallucinations get, Vegas can match the nightmare horror for horror. Visually, Gilliam and his team make tremendous use of the city's neon landscape. A driving montage down the strip uses rear projection and cutaways to melt and bend the surrounding signs and advertisements. Overdone hotel wallpaper and carpets come alive and swallow the patrons. Cinematographer Nicola Pecorini (The Order

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is nearly formless in its construction, though it solidifies over each selective viewing. To carry the drug metaphor, you build a kind of tolerance, gaining an ability to maintain the more you partake. Though I wouldn't have said so when it was first released, I'd hazard to call it Terry Gilliam's most together movie. Not necessarily his best, but possibly the one where he is most in command of the elements. For all the bedlam depicted onscreen, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is meticulously choreographed. Many of the scenes of Gonzo and Thompson wandering through the casinos while going off their heads play for extended lengths without much cutting. In these, they are each performing independent actions, including interacting with crowds of extras. Sometimes it's super complicated, like the hotel bar when they first get to town, just before all the other drinkers turn into lizards; other times, it's more simple. When Gonzo argues their way into a Debbie Reynolds concert, Thompson stays by himself, doing more drugs on the sly. Gilliam keeps the shot wide and lets the actors move around the frame. You could watch either of them do their thing, they are both doing something interesting, and yet it also works perfectly in tandem.

Naturally, with an experience like Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, there is no real exit, no grand conclusion to be had. The trip ends--in both senses of the word. The vacation is over, the vacationers have to come down off of the high. Yet, Gilliam gives us a satisfying wrap-up anyway. In his way, he has contained the chaos, and so there is a relief in making our way back out of it. Rubber hits the road, and Hunter S. Thompson heads back to Los Angeles, a smile on his face, remembering all the devils in the preceding details, having survived to return to some kind of perceived normalcy. And yet, that grin also says it's never going to be completely over: the craziest diamonds always shine on.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Screen captures are from the DVD, not the Blu-Ray.

Thursday, April 28, 2011

CRITERION COLLECTION SALE AT AMAZON

Hey, all.

I apologize for my absence in the last couple weeks. I didn't update at all last week, I've been really behind on my work. Expect three reviews coming up in rapid succession to catch me up. I have Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, Kes, and Smiles of a Summer Night all queued up to review.

In the meantime, you should know that there is a big sale going on at Amazon, with a large number of Criterion discs being up to 52% off. It's not an officially promoted sale from what I can tell, so no idea when the deals will end, but check out the Amazon page devoted to the Collection and browse the prices.

Criterion at Amazon

I apologize for my absence in the last couple weeks. I didn't update at all last week, I've been really behind on my work. Expect three reviews coming up in rapid succession to catch me up. I have Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, Kes, and Smiles of a Summer Night all queued up to review.

In the meantime, you should know that there is a big sale going on at Amazon, with a large number of Criterion discs being up to 52% off. It's not an officially promoted sale from what I can tell, so no idea when the deals will end, but check out the Amazon page devoted to the Collection and browse the prices.

Criterion at Amazon

Tuesday, April 12, 2011

LE CERCLE ROUGE (Blu-Ray) - #218

"Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, drew a circle with a piece of red chalk and said: 'When men, even unknowingly, are to meet one day, whatever may befall each, whatever the diverging paths, on the said day, they will inevitably come together in the red circle.'"

Fate plays an important role in Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1970 crime movie, Le cercle rouge. Though, I am not sure “fate” is the right word. In this hardboiled world, it’s more like the cynicism of happenstance, or an absence of faith in the human animal. Mankind will always make the wrong choice, and the wrong choice inevitably leads to only one outcome.

There are two storylines that form Melville’s red circle. One involves an escaped convict and the policeman he got away from. Vogel (Gian Maria Volonté) was being transported by train to his trial. His escort was Captain Mattei (André Bourvil), an older, no-nonsense police detective. When Vogel slips his shackles and jumps from the train, Mattei starts a manhunt that will last the length of the picture. He must bring the crook back in order to save face.

At the same time, another thief is being released from prison. Corey, played by French matinee idol and Melville regular Alain Delon, has his jail sentence cut short on the promise that he will pull a jewel heist for the guard arranging his release. The guard has inside info on the security system at a jewelry shop, and his cut when Corey cleans the place out will allow him to retire. Corey doesn’t really want the gig, he doesn’t want to get out of the clink to go right back in, but what choice does he have? Not that much is waiting for Corey on the outside. His girl has left him for Rico (André Ekyan), the gangster who betrayed him when he was sent up the river. Corey’s first order of business is getting some walking-around money from Rico; it’s also his first mistake.

Once both Vogel and Corey are on their path, circumstances immediately go into motion to bring them together. Cleverly, Melville creates a literal circle around the two men, one that will close in around them. Mattei traces the ring on a map, indicating the locations of the road blocks meant to capture Vogel. They fail, and Vogel becomes Corey’s partner in the jewel heist. He also brings in the third man, an ex-cop by the name of Jansen (legendary French actor Yves Montand). Though a drunk with the DTs, Jansen is an ace marksman, which the guys will need. He’s also a security expert, and so he cases out the target to make sure the intel is correct.

Le cercle rouge is famous for its 25-minute heist sequence, in which no dialogue is spoken. It immediately brings to mind the similar silent robbery in Jules Dassin’s Rififi [review], though reportedly Melville was planning his rip-off several years prior to the Dassin picture and actually postponed Le cercle rouge as a result. Though much is made of the quietness of this astounding section of film, the entire picture has a resounding silence throughout. Little is said in Le cercle rouge, there are no wasted words. These are men who all have a job to do, regardless of what side of the law they are on, and they will do it with a kind of religious devotion. Activity replaces spirituality in Melville’s world. Occupation is more important than vocation. The appropriation of Oriental philosophy for this kind of existential code of conduct is similar to Melville’s portrayal of the stoic gun thug in Le samourai. He, too, was played by Delon, and both films share lookalike nightclub settings.

The nightclub here is owned by Santi (François Périer), a stand-up guy and a friend of Vogel. Mattei is convinced Santi will be the key to finding the fugitive, but the club owner has the most clear statement of existential intent in the film when he insists that he cannot inform on his friend and never can be persuaded to do so because, fundamentally and deep down, he is not an informer, it is not his nature, simple as that. Mattei will challenge this self-perception and offer Santi a difficult choice, one that will violate his code and force him to weigh the consequences of not doing so. It’s an ethical conundrum worthy of Sartre, and the policeman is employing his own harsh philosophy: “All men are guilty. They're born innocent, but it doesn't last.” There is only one possible outcome to all of this as far as Mattei is concerned; after all, he is the one drawing the circle. Other visual metaphors reinforce the sameness in all beings, from the prevalence of beige raincoats to the dance routines at Santi’s club, featuring a troupe of gals all dressed alike, all moving alike, all exactly the same.

Le cercle rouge is shot with a meticulous rigor by Henri Decaë, and then edited with precision by Marie-Sophie Dubus, with Melville sitting by her side. The movie is pieced together with a clear attention to detail and an obvious devotion to narrative integrity. Melville employs few tricks, but the ones he does use add an efficiency to what is technically a long movie--though one that never shows its length. Zooming in on key points around the jewelry store, the fades in the montage when Jansen makes his bullets (almost like flipping pages in a book), or the choppy hallucinations when the marksman is drying out all enhance the corresponding activity without overdoing it. There are also nice touches in the art direction, such as Jansen’s vertically lined wallpaper and the doorway that disappears into the pattern, that add to the mood without overpowering their specific scenes. I’m also quite found of the subtle character details given to Mattei: the framed photos of an absent wife and the apartment full of Siamese cats suggest a man who is lonely, and yet at peace.

Melville prefers long takes to quick cuts, particularly as the robbery is planned and executed. We witness each step, each careful action. Most of the time, he is content to sit and watch, but there is also plenty of camera movement. Actually, one of Le cercle rouge’s first shots is an astonishing pull back from Mattei and Vogel’s train window, starting on the police detective as viewed through the glass, and then soaring off into the air, the window becoming smaller in the distance, the length of the train becoming more evident. It’s almost as if Melville intended to show how tiny the individual person is within the world, just one small passenger on the journey of life, subject to wherever that journey will take him or her.

It’s also a scene that looks phenomenal on Blu-Ray. Image quality is of utmost importance in a film like this, where so much relies on the audience seeing every minute detail clearly. Many of the scenes take place in darkness, and even in the daytime the skies are gray and cloudy, but the picture is rendered well enough that everything is visible, even within the intended shadows. The film stock has a lovely grain to it, adding to the grittiness of the montage. I originally saw Le cercle rouge seven years ago on a theatrical tour, and it only impresses me more each time I see it in a new, updated format. The new edition mirrors and carries over all the extras from the old edition, but cinema obsessive’s will still want it for the improved picture and sound.

Then again, La cercle rouge would continue to impress even without new technological innovations. It is a movie where the barebones construction and near-monastic avoidance of excess masks its hidden depths. The further you peer into it, the more gears you see turning in the background. It takes a lot of complicated work for a movie to appear this clear-cut, and when it comes to the mechanics of motion pictures, Jean-Pierre Melville was a master.

This disc was provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.

Screen captures are from the DVD, not the Blu-Ray.

Fate plays an important role in Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1970 crime movie, Le cercle rouge. Though, I am not sure “fate” is the right word. In this hardboiled world, it’s more like the cynicism of happenstance, or an absence of faith in the human animal. Mankind will always make the wrong choice, and the wrong choice inevitably leads to only one outcome.

There are two storylines that form Melville’s red circle. One involves an escaped convict and the policeman he got away from. Vogel (Gian Maria Volonté) was being transported by train to his trial. His escort was Captain Mattei (André Bourvil), an older, no-nonsense police detective. When Vogel slips his shackles and jumps from the train, Mattei starts a manhunt that will last the length of the picture. He must bring the crook back in order to save face.

At the same time, another thief is being released from prison. Corey, played by French matinee idol and Melville regular Alain Delon, has his jail sentence cut short on the promise that he will pull a jewel heist for the guard arranging his release. The guard has inside info on the security system at a jewelry shop, and his cut when Corey cleans the place out will allow him to retire. Corey doesn’t really want the gig, he doesn’t want to get out of the clink to go right back in, but what choice does he have? Not that much is waiting for Corey on the outside. His girl has left him for Rico (André Ekyan), the gangster who betrayed him when he was sent up the river. Corey’s first order of business is getting some walking-around money from Rico; it’s also his first mistake.

Once both Vogel and Corey are on their path, circumstances immediately go into motion to bring them together. Cleverly, Melville creates a literal circle around the two men, one that will close in around them. Mattei traces the ring on a map, indicating the locations of the road blocks meant to capture Vogel. They fail, and Vogel becomes Corey’s partner in the jewel heist. He also brings in the third man, an ex-cop by the name of Jansen (legendary French actor Yves Montand). Though a drunk with the DTs, Jansen is an ace marksman, which the guys will need. He’s also a security expert, and so he cases out the target to make sure the intel is correct.

Le cercle rouge is famous for its 25-minute heist sequence, in which no dialogue is spoken. It immediately brings to mind the similar silent robbery in Jules Dassin’s Rififi [review], though reportedly Melville was planning his rip-off several years prior to the Dassin picture and actually postponed Le cercle rouge as a result. Though much is made of the quietness of this astounding section of film, the entire picture has a resounding silence throughout. Little is said in Le cercle rouge, there are no wasted words. These are men who all have a job to do, regardless of what side of the law they are on, and they will do it with a kind of religious devotion. Activity replaces spirituality in Melville’s world. Occupation is more important than vocation. The appropriation of Oriental philosophy for this kind of existential code of conduct is similar to Melville’s portrayal of the stoic gun thug in Le samourai. He, too, was played by Delon, and both films share lookalike nightclub settings.

The nightclub here is owned by Santi (François Périer), a stand-up guy and a friend of Vogel. Mattei is convinced Santi will be the key to finding the fugitive, but the club owner has the most clear statement of existential intent in the film when he insists that he cannot inform on his friend and never can be persuaded to do so because, fundamentally and deep down, he is not an informer, it is not his nature, simple as that. Mattei will challenge this self-perception and offer Santi a difficult choice, one that will violate his code and force him to weigh the consequences of not doing so. It’s an ethical conundrum worthy of Sartre, and the policeman is employing his own harsh philosophy: “All men are guilty. They're born innocent, but it doesn't last.” There is only one possible outcome to all of this as far as Mattei is concerned; after all, he is the one drawing the circle. Other visual metaphors reinforce the sameness in all beings, from the prevalence of beige raincoats to the dance routines at Santi’s club, featuring a troupe of gals all dressed alike, all moving alike, all exactly the same.

Le cercle rouge is shot with a meticulous rigor by Henri Decaë, and then edited with precision by Marie-Sophie Dubus, with Melville sitting by her side. The movie is pieced together with a clear attention to detail and an obvious devotion to narrative integrity. Melville employs few tricks, but the ones he does use add an efficiency to what is technically a long movie--though one that never shows its length. Zooming in on key points around the jewelry store, the fades in the montage when Jansen makes his bullets (almost like flipping pages in a book), or the choppy hallucinations when the marksman is drying out all enhance the corresponding activity without overdoing it. There are also nice touches in the art direction, such as Jansen’s vertically lined wallpaper and the doorway that disappears into the pattern, that add to the mood without overpowering their specific scenes. I’m also quite found of the subtle character details given to Mattei: the framed photos of an absent wife and the apartment full of Siamese cats suggest a man who is lonely, and yet at peace.

Melville prefers long takes to quick cuts, particularly as the robbery is planned and executed. We witness each step, each careful action. Most of the time, he is content to sit and watch, but there is also plenty of camera movement. Actually, one of Le cercle rouge’s first shots is an astonishing pull back from Mattei and Vogel’s train window, starting on the police detective as viewed through the glass, and then soaring off into the air, the window becoming smaller in the distance, the length of the train becoming more evident. It’s almost as if Melville intended to show how tiny the individual person is within the world, just one small passenger on the journey of life, subject to wherever that journey will take him or her.

It’s also a scene that looks phenomenal on Blu-Ray. Image quality is of utmost importance in a film like this, where so much relies on the audience seeing every minute detail clearly. Many of the scenes take place in darkness, and even in the daytime the skies are gray and cloudy, but the picture is rendered well enough that everything is visible, even within the intended shadows. The film stock has a lovely grain to it, adding to the grittiness of the montage. I originally saw Le cercle rouge seven years ago on a theatrical tour, and it only impresses me more each time I see it in a new, updated format. The new edition mirrors and carries over all the extras from the old edition, but cinema obsessive’s will still want it for the improved picture and sound.

Then again, La cercle rouge would continue to impress even without new technological innovations. It is a movie where the barebones construction and near-monastic avoidance of excess masks its hidden depths. The further you peer into it, the more gears you see turning in the background. It takes a lot of complicated work for a movie to appear this clear-cut, and when it comes to the mechanics of motion pictures, Jean-Pierre Melville was a master.

This disc was provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.

Screen captures are from the DVD, not the Blu-Ray.

Friday, April 8, 2011

WHITE MATERIAL (Blu-Ray) - #560

White Material, the latest film from French director Claire Denis, is an elusive, yet intriguing drama about social privilege, personal passion, and the delusions and myopia born out of each. The script, co-written by Denis and Marie NDiaye, uses real-world locations and timely political problems to create an otherworldly narrative, one that takes what is familiar and holds it close even as it smuggles these elements into a place totally separate from any logic we may recognize.

The great Isabelle Huppert stars as Maria Vial, a French citizen living in Africa. She and her husband have been running a coffee plantation for several years, and they have apparently lived on the continent for longer. It's harvest time for their struggling business, but a civil war has caused all of their workers to run off scared. The French government is also pulling out of the region and is encouraging its citizens to do the same. Maria's husband, André (Christopher Lambert), would rather cut his losses and go, even going so far as trying to strike a deal with the local "mayor," Chérif (William Nadylam), to take the land off his hands. Chérif is forming a militia to fight the incoming rebels. This ragtag bunch seems no more or less thuggish than the government soldiers. It's hard to tell which side is which.

Maria sticks to her belief that she can get through this, and much of White Material is about her resisting all urgings to stop and finding other workers to replace the ones who left. She is stubborn to any argument that doesn't jibe with her own belief of how things are going, a character flaw she extends to her son, Manuel (Nicolas Duvauchelle). Everyone sees that the teenager is a deadbeat--he spends the first half of the movie locked in his bedroom, refusing to come out--but Maria refuses to hear a negative word said about him. This is a mother's prerogative, I suppose; by extension, she is also mother of the coffee she has been growing, the matriarch of this homestead. She won't give up on her children no matter what.

Not even when the rebellion has come through her front gate. The most notorious rebel figure is an enforcer (Isaach de Bankolé) talked about in hushed whispers, either out of fear or awe depending on who you're with. They call him the Boxer, and his wanted posters are large murals painted on the sides of buildings. He is depicted with a belt of machine gun bullets draped over his chest and posed as readying to throw a punch. The image we get of him is different: he is wounded and nearly incapacitated, seemingly only carrying on via an ice-cold determination to not be beaten. He levels no threats at Maria--he doesn't have to.

White Material unfolds according to its own internal rationale. Though not exactly plotless, it does not conform to any textbook screenplay outline. Its main drive is for its characters to beat the amorphous deadline that hangs over the war-torn region. Maria must harvest her coffee before the government army comes sweeping through the town, before the Boxer rises up with his rebel soldiers--many of whom are children--to battle for dominance. Denis cuts her film to the flow of dark, ambient rhythms. The music for White Material was composed by the Tindersticks, whose morose melodies have become a staple of her work*. These sinister soundscapes trade airtime with revolutionary-themed reggae music, records spun by a local radio DJ between coded messages to citizens and freedom fighters. He joins a tradition of cinematic AM/FM instigators that includes Super Soul in Vanishing Point [Blu-ray]

The more desperate the situation becomes, the more determined Maria is to finish the job. She hides threats sent to her by unseen enemies and lies to her new workforce. In direct relation to this, Manuel goes further off the deep end, though his intentions aren't clear at first and his true motives are surprising. Essentially, you can't beat them all, so you have to join somebody. The less that Maria can get others to do, the more control wrested from her hands, the harder she pushes back. It takes a tremendous emotional toll on her, and Huppert tip toes around this woman's psychosis so as not to make her seem overly crazy or even all that unreasonable. While she does possess a manic energy, there is a calmness to her single-minded mission that gives her balance. At times, we think that maybe she really can pull this off.

But, alas, good intentions disappear in the miasma. As White Material moves toward its climax, the mis-en-scene becomes more choppy, the storytelling more intentionally muddled. The whole region is losing its mind and collapsing in on itself, and so we aren't supposed to know exactly who is doing what to whom. To preserve her isolation, Maria has given over to the savagery that she has been rejecting, and there is no telling what is next for her. A fog doesn't literally roll in, but smoke from a burning fire does add a visual facet to the cloudy metaphor. The conclusion of White Material has an element of the unknowable. Denis is more concerned with the impression it will leave than your literal translation of what you have seen. The haze may not clear, and that may be exactly the point: you can flee these kinds of crises, but they will still be there, never going away.

* For those interested, a full boxed set of the Tindersticks music from Calire Denis' films is coming soon. Details here.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Friday, April 1, 2011

SILENT NARUSE - ECLIPSE SERIES 26

It's sad to read in the liner notes for the new Eclipse set, Silent Naruse, that of the twenty-four films that the Japanese writer/director Mikio Naruse made in his first years of filmmaking, only the five contained here still exist. An early cinematic pioneer whose career spanned nearly half a century, he made eighty-nine films in total, and only about half of them have survived the decades since. In an age when film seems so permanent, and even the worst box office dud gets preserved in high-definition for future generations to suffer through, we can't forget that, once upon a time, the art of movies was mutable.

Thus, Mikio Naruse is a director that more of us probably know by name rather than by his work. He was an artist whose specialty was what was termed the "woman's picture." Like Douglas Sirk in the U.S., Naruse made movies that, for the most part, focused on family drama with a female center. Many of his films were emotional tales that explored the unique struggle of women in Japanese society--particularly those who lived on the fringe, either economically or socially, or sometimes both, one dictating the other. This peek into his earliest work confirms that these were issues he was concerned with from pretty much the get-go, though the core ideas would be ones that would develop over time, along with his style.

The 1931 short Flunky, Work Hard (28 minutes) is the oldest surviving film from Naruse. It's a blend of comedy and drama, centered around the family of a meek insurance salesman (Isamu Yamaguchi) struggling to make ends meet--so a rare entry where the main character is actually a man. If he can just seal the deal with a large neighbor family, he thinks things will be all right, but his son (Seiichi Kato) keeps getting into fights and the salesman fears it will cause him to lose the account to his competitor. (In one funny scene, the salesman lets the family's kids play leap frog over him so they'll like him better than the other guy). The movie has broad humor, including little boys hitting each other on the head with their shoes and similar physical gags, but it also takes a turn for the dramatic. The final scenes have an O. Henry element, with events growing bittersweet and ironic.

Most striking, though, is Naruse's impressionistic experiments, using double exposures and mirror images and other camera tricks to mimic his hero's anxiety. Though rudimentary by today's standards, and possibly even by Hollywood's special effects level at the time, it is admirable to see a filmmaker employing every trick at his disposal to enhance what is essentially a fluffy one-off.

There are no such effects in No Blood Relation (79 mins.), released the following year. In fact, it's like Naruse only has one card to play: he just discovered the emphatic zoom. There is a lot of quick pushes as characters react to one another in this middling drama from screenwriter Koga Noda, Ozu's regular writer. The story revolves around a young girl (Hisako Kojima) who was abandoned by her mother, Tamae (Yoshiko Okada), when she went off to be an actress in America. Tamae returns with fame and fortune in hand, and she and her brother, a two-bit hood, try to get the girl back from her ex-husband (Shinyo Nara). He is on his way to debtor's prison, having run his business into the ground, and so it opens up a door for Tamae, even though the girl sees Masako (Yukiko Tsukuba) as her real mother. She's never known Tamae and rejects her.

No Blood Relation is based on a play by Shunyo Yanagawa, and it is primarily a depiction of the push and pull between the two mothers--though Masako is a good person and so not nearly as forceful as her rival. Plus, the concerns over money mean she has to work and worry about paying rent, whereas Tamae has unlimited resources. There's not much more to it than that, and to be honest, No Blood Relation can be a little slow going. There is some occasional comic relief from Tamae's brother and his purse-snatching cohort, but that tends to be pretty mild also. It's not that No Blood Relation is bad, it just didn't strike me as having much to distinguish it from any other average melodrama of the period. By its predictable happy ending, I was ready to move on.

Within the next year, Naruse's technique would grow more sophisticated. His agility with film language would become more apparent, and he would also transition into some of the thematic elements that would define his career, foreshadowing even his most well-known film, the 1960 feature When a Woman Ascends the Stairs [review].

1933's Apart From You (60 mins.) displays a surprising confidence and a more natural flow than No Blood Relation. Naruse takes over screenplay duties again, as he did in Flunky, to tell the story of two geisha of differing ages. Kikue (Mitsuko Yoshikawa) is older and starting to lose her beauty and her motivation, and Terugiko (Sumiko Mizukubo) is the younger woman whom she has taken under her wing. Kikue's homelife has turned difficult, her son (Akio Isono) doesn't respect her and resents her career choice. As he falls in with a bad crowd, it's up to Terugiko to help keep him from throwing his mother's good efforts away. Terugiko has only became a working girl to support her family, and her own sacrifices illuminate the struggles Kikue has endured to give her child a better life.

Apart from You is a good example of how traditional stories and even heavy melodrama can, despite their familiarity, be effective in the right hands. For the most part, Naruse drops the heavy zooms and develops a more elegant mis-en-scene. At just an hour, the story never lingers too long, and he relies more on suggestion than overwrought dramaturgy. In particular, the director's focus on smaller details, on the individual components of everyday life, create a more effective portrait of what are essentially average people. The focus on the holes in the son's socks, and the humorous solution that Terugiko's little brother comes up with bring these characters to life by exposing their most minor concerns. If our day-to-day is the accumulation of the small stuff, then maybe the big stuff can be seen as small, too. The editing style, favoring more individual shots and cutaways than was popular during this period, emphasize Naruse's mosaic approach, the bigger picture emerging as he arranges more and more of the smaller ones.

Sumiko Mizukubo is a surprising screen presence. Her performance has an effortless charm that, through considered gestures and expression, creates an immediate intimacy with the audience. Though we are told that society judges girls who become geisha harshly, Mizukubo makes Terugiko human, and so she draws our sympathy rather than our condemnation. The actress only made 18 films in her career, including one with Hiroshi Shimizu in the same year as Apart from You; alas, none of the others seem to be readily available.

Also from 1933, Every-Night Dreams (65 mins.) is an obvious companion to Apart from You. Based on a story by Naruse, and with a screenplay by Tadao Ikeda, it has a heavier tone than the other films. This somber silent tells the story of Omitsu (Sumiko Kurishima), a single mother who works as a geisha in a seamy portside bar to support her son (Teruko Kojima). Her existence is a dour one, but she carries on valiantly out of love for her boy. When her husband (Tatsuo Saito) returns three years after he abandoned them, it threatens to disrupt the balance that Omitsu created. He swears he's changed, and he does try to get a job, but things don't go so well--particularly after the husband loses his cool when a client that loaned Omitsu money tries to collect in non-monetary ways.

Naruse uses a plot device similar to one in Flunky in Every-Night Dreams: their son getting hit by a car forces the parents to reassess what they are doing. It's more O. Henry irony, with the desperate measures of desperate times yielding disastrous results. This one ends on a downbeat, and once again, Naruse has cast his lead well. Sumiko Kurishima is a ghostly beauty whose serious manner lends a stony weight to how she moves and acts. There is much gravitas here, and Naruse and cinematographer Suketaro Inokai, who shot every movie in Silent Naruse except Flunky, continue to dial back the dramatic camera work and instead work simply, using the seaside setting to capture the realism of Omitsu's squalid existence. Some of the writing still goes for the big emotion, but the way the actors downplay what could be weepy and overdone lends the story machinations credibility that in turn inspires the audience to have faith in the integrity of the montage.

The final movie in the Eclipse set was also the last silent film Mikio Naruse made, and his final at Shochiku. 1934's Street Without End (88 mins.) was based on a popular novel by Komatsu Kitamura, and the screenplay was adapted by Tomizo Ikeda. Like the film that preceded it, Street Without End also relies on the plot device of an automobile accident, though this time coming early in the movie to set up where the rest of the story will go. Setsuko Shinobu stars as Sugiko, a waitress in a diner who, at the time she is hit by the car, is trying to decide between marrying her boyfriend (Ichiro Yuki), who will be going against his family to be with her, or to take an offer to become a film actress. Her head is in the clouds of these possible scenarios when Yamanouchi's car careens into her. The handsome, moneyed bachelor (Hikaru Yamanouchi) quickly spirits her away, leading to her losing both the marriage and job offers, but replacing it with something else.

Street Without End, in a way, is a rags-to-riches-to-rags tale for the bulk of its characters. Sugiko's marriage to Yamanouchi isn't a good one: he also is going against his family, and his busybody mother and sister (Fumiko Katsuragi and Nobuko Wakaba) refuse to be pleasant about his "selfishness." At the same time, one of Sugiko's friends (Chiyoko Katori) takes the opportunity her pal missed, and she takes along her own boyfriend (Shinichi Himori), a painter, getting him a job in the movie studio art department after she signs on as an actress. These choices bring consequences, too. Nothing overly terrible, but things were easier, more comfortable, back at the tea shop. Naruse is probing his characters, pushing them to ask themselves what it is they want versus what it is they have. He is also critiquing the strict adherence to tradition and how it leads to disappointment and class resentment.

Naruse has all but removed the overtly demonstrative camera moves by the time of Street Without End, settling into a far more considered approach for how he puts his scenes together. Watching Silent Naruse front to back, you can see his style become more and more grounded. The events themselves pack enough punch, to bang the audience over the head with visual histrionics would only undermine the truth and humanity at the heart of the script. The actors show restraint, as well, preferring a quiet manner and subtle gesture to the big expressions that most people (unfairly) think of when they think of silent cinema.

Admittedly, the closing film isn't all that electric, and even patient viewers might find that Street Without End drags from time to time, but the final scenes offer an uneasy balance between empowerment and disillusionment; the last fadeout has tremendous impact. Sugiko's stillness leaves the next move up to the audience. What lies ahead is probably only more struggle, but the valiance of her resolve is clear, even if her satisfaction is not.

The Silent Naruse Eclipse set brings together five movies on three discs. The first two discs have two movies apiece--Flunky, Work Hard and No Blood Relation on one, Apart From You and Every-Night Dreams on the other. The longest movie in the set, Street Without End, gets the last DVD to itself.

All five films are full frame, and the discs were struck from the best sources available, and so it can be a take-it-as-it-comes affair. The older the film, the more the damage, with regular scratches and noise on the black-and-white image. Luckily, the damage is not persistent and never so pronounced as to obscure the image. Every-Night Dreams has the softest picture, and it's more bleached and white than the others. The boxed set doesn't boast a full-scale clean-up, but the digital authoring is good, so it's clear Criterion took the best care with putting the product together as they could. Given how much of a miracle it apparently is that these movie exist at all, we should just thank our lucky stars that they are now preserved in a format that will last.

Apart from You

The movies are all presented as either completely silent or you have the option of playing new scores by Robin Holcomb and Wayne Horvitz. These need to be turned on at the main menu. The pair provide solid musical accompaniment, laying a foundation for the movies without overshadowing the events onscreen. The scores are piano and violin mostly, with some percussion and other instruments used sparingly, and my only complaint is that, occasionally, like in No Blood Relation and Apart From You, they added passages that got a little jazzy for my taste.

The Eclipse boxed set Silent Naruse is a wonderful time capsule, the only remaining snippet of the great Japanese director's early career. Collecting his five surviving films from the silent era--and indeed, the earliest he has available--it shows how he honed his craft, going from family comedy to full-blown melodrama, elevating the low-end "women's picture" to high art. The sailing is not all smooth, some of these films can be slow going, but the pairing of Apart from You and Every-Night Dreams in particular has a sincerity that allows the material to transcend the rough patches.

Every-Night Dreams

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)