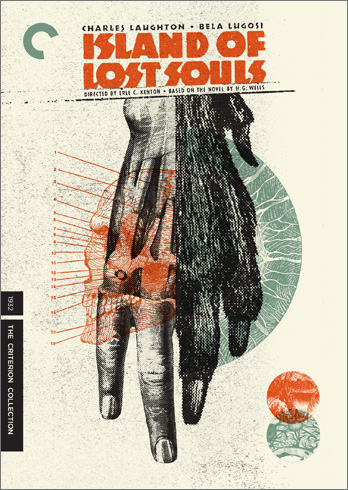

It's rather astonishing what a strange film Island of Lost Souls is. Directed by Erle C. Kenton in 1932, it's the first cinematic adaptation of H.G. Wells' The Island of Dr. Moreau. Though the story and various depictions of the titular doctor and the beasts he creates has since taken a permanent place in the pop culture lexicon--in most recent memory, the mad scientist was played by Marlon Brando

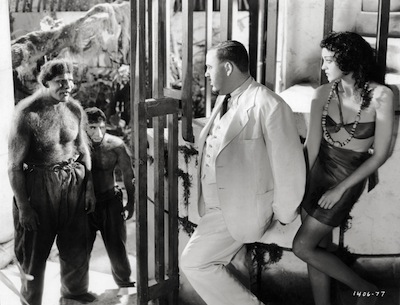

The story is pretty simple. Edward Parker (Richard Arlen) was set adrift when the ship he was sailing on sank. He is picked up by a cargo ship and cared for by Montgomery (Arthur Hohl), a disgraced doctor charged with guarding the wildlife being transported to an uncharted island. Parker runs afoul of the ship's drunken captain, and the seaman ditches him overboard with the animals when they reach their destination. This strands Parker and puts him at the mercy of Montgomery's boss, the slippery Dr. Moreau (Charles Laughton). The strange practitioner is at first concerned with what Parker might spy on his island, but then he sees an opportunity. Moreau has been creating creatures that are part human, part animal. The most perfect realization of his hybrid process is also the only female: Lota, the Panther Woman (Kathleen Burke). He doesn't trust the other aberrations around the woman, but maybe letting her mingle with Parker will reveal her true social capabilities. Can the Panther Woman love?

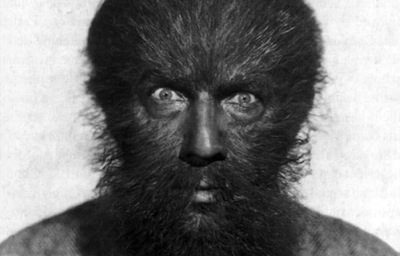

Island of Lost Souls is an impressive display of early cinematic special effects. Kenton and his team, which includes Wally Westmore on make-up and art director Hans Dreier (both of whom worked regularly with Billy Wilder and Preston Sturges), create an eerie, otherworldly environment for Moreau and his creatures. Thick foliage hides both Moreau's fancy laboratory and the village of the beast-men. They are led by the Sayer of the Law (Bela Lugosi), a bearded biped who seems slightly more evolved than his brethren, though still beholden to Moreau's strictures. The rules of the community are recited in a call and response ritual. "Are we not men?" they cry, and by way of proving it, adhere to the orders not to spill blood or to crawl on all fours like an animal. Some are closer to reverting to the old ways than others, and the least evolved are enslaved to turn the great wheel generating Moreau's power. It's a primitive fiefdom with the bad doctor as the King.

The make-up for the animal men is fantastic. They aren't just hairy beasts, different individuals represent different animals--a pig, a dog, a gorilla. Some look like Neanderthals, others look like something out of a carnival sideshow. Moreau is their ringmaster, and Laughton oozes a vile charisma. His words practically congeal into slime, and his cruel streak is satisfied through violent rule. He undergoes an almost sexual ecstasy when cracking his whip. His aptly named "House of Pain," where beast-men are taken for punishment, is like an S&M dungeon.

Parker's fate pretty much doesn't matter next to these more bizarre elements. Plus, Arlen is kind of a stiff and the character is a real heel. He makes out with the Panther Woman, something he fails to tell his fiancée (Leila Hyams) when she comes to rescue him--though she most likely suspects something when he's so eager to save the island native on their way out. By that point, their trajectory has splintered off from Moreau's, and honestly, there isn't much tension waiting to see the outcome of their flight from the madness. As with any science-gone-wrong film, the pay-off is seeing the egomaniac brought down. The implications of what might happen to Moreau in his own House of Pain are gruesome. Progress means little if you treat those around you with selfish pride, regardless if they be man or beast.

When you see a movie like Island of Lost Souls that is almost eighty years old and yet still has the power to shock, it makes you wonder why so many contemporary horror films are so ineffective at what they do. The endless parade of remakes, the plotless slasher films and torture porn--it all pales next to Erle C. Kenton's ambition and his precise storytelling. It's easy to gross someone out, it's even easier to bore them, but to elicit genuine chills, that's another talent entirely. Island of Lost Souls, like King Kong

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVD Talk.

Also, please note that the images here are promotional stills and not taken directly from the Blu-Ray.