In addition to my Criterion reviews, here are other reviews film fans of similar tastes might find of interest from the last month:

IN THEATRES...

* Coraline, the long-awaited new effort from Nightmare Before Christmas-director Henry Selick is a pretty looking dud.

* Two Lovers, a rough and often tough-going romantic tale about the ups and downs of the heart. With Joaquin Phoenix and Gwyneth Paltrow.

Also, check out the reviews in the Portland International Film Festival section of my Confessions of a Pop Fan blog. I cover many foreign movies that will hopefully be coming to a theatre or DVD shelf near you very soon...or in some cases, hopefully not.

ON DVD...

* Cannery Row, a Steinbeck adaptation that falls short of the mark thanks to a strained and hokey stylistic nostalgia. With Nick Nolte and Debra Winger.

* Far from the Madding Crowd, John Schlesinger reteams with Julie Christie in an epic, romantic adaptation of Thomas Hardy.

* A Guide to Recognizing Your Saints, an interesting but all too familiar coming-of-age tale that asks you to believe that Shia LaBeouf will become Robert Downey Jr.

* In the Electric Mist, Bertrand Tavernier tackles a James Lee Burke novel with mixed but mostly good results. Tommy Lee Jones stars as Burke's Detective Dave Robicheaux.

* Murnau, a collection of six of F.W. Murnau's silent films from Germany, including Nosferatu, Faust, and The Last Laugh

* Natalie Wood Signature Collection, a new boxed set that is mostly full of misses from the Warners back catalogue. It does contain the new edition of Splendor in the Grass, though.

* The Sidney Poitier Collection, three good movies, including Martin Ritt's Edge of the City with John Cassavetes and Something of Value with Rock Hudson, sit next to one clunker. Three out of four, still pretty good.

Saturday, February 28, 2009

ALI: FEAR EATS THE SOUL - #198

I've been meaning to watch Ali: Fear Eats the Soul since I reviewed Magnificent Obsession last month. Rainer Werner Fassbinder was probably Douglas Sirk's most fervent and notorious student, and Ali one of the films where the German director distilled Sirk's melodrama into a more modern European landscape.

Emmi (Brigitte Mira) merely wanted to get in out of the rain when she ducked into the Asphalt Bar, but she got much more then she bargained for. Taunted by a snotty woman whose advances he had rejected, Ali (El Hedi Ben Salem) asks Emmi to dance. The fifty-something cleaning lady obliges, and a love affair begins. The Asphalt is a hangout for Arab immigrants, and it's a completely different world than the one that Emmi takes Ali back to when he walks her to her apartment. Yet, he stays overnight and never leaves. The two eventually get married, a union that brings them as much grief as it does happiness. 1970s Germany, like many places, was not a place where interracial marriages were common, and with twenty years or more separating Emmi and Ali, it's like one taboo has been grafted onto another to make a whole new taboo entirely.

The plot takes the familiar Sirkian dilemma and twists it in a new direction. Changing social mores allowed Fassbinder to get away with a political and emotional scenario the Hollywood codes of the 1950s would never have let Sirk deal with. It's a trick director Todd Haynes, who recorded a video introduction for this DVD, would borrow thirty years later for Far From Heaven

It is possible for an homage to be too much of an homage, and Fassbinder veers dangerously close to that edge. The plot of Ali: Fear East the Soul is wafer thin, and at times the writer/director piles on the heavy emotions to the point of overload. While the fantastic color scheme of the movie, utilizing solid blocks of garish color to suggest the characters are trying to dress life up in a happiness they don't really possess, calls to mind Sirk's 1950s pastels, other fumblings with the Sirk toolbox have the faint odor of postmodern irony, as if Fassbinder is slightly above the concerns he chronicles. The gossipy hens who live in Emmi's building, for instance, seem plucked right out of an old television show, and Fassbinder's own turn as the lazy German husband who hates the Turks and Arabs stealing his job just needs a beer stain on its wife-beater T-shirt to make the caricature complete. Fassbinder is just one of the many stiff actors to appear in Ali. The mechanical step-turn-look blocking is more like a Bresson-directed non-performance than the quiet operatics Sirk peddled in.

I guess I can't really say I know what 1970s Germany was actually like, but much of the racism struck me as overwrought and even a tad cartoony. Emmi is ostracized, given the most scowly dirty scowls, and her friends are more than open with their polemics and urban legends about the habits of black men. Yet, race also provides some of the more interesting elements of the larger story. Emmi herself is rather cavalier about mentioning having belonged to the Nazi party or taking Ali to one of Hitler's favorite restaurants for dinner after their marriage ceremony. She carries within herself an underlying racism that Fassbinder saw in Germany, a hypocrisy of a supposedly enlightened present that has not really eradicated the sins of the past, just repositioned them. Emmi has never had to confront her own feelings about race, and loneliness is not a convenient enough excuse to fully erase deeper prejudice.

The movie actually improves in its third act when Emmi's friends, family, and neighbors adjust to her new husband. Now that Emmi doesn't have to deal with their scorn, she begins to objectify Ali and show him off. There was always a kind of motherly element to their relationship that sometimes garners some unintentional laughs, as if Fassbinder had accidentally spliced a little Harold and Maude

The phrase "fear eats the soul" is a Moroccan saying that Ali teaches Emmi, and it describes the overall problem the two face. They let the worries of the outside world distract them from the interior and private life that nourishes them. Fassbinder also plays it a little on the nose by giving Ali a physical ailment that is literally eating away at his insides, but that seems more shoehorned in for an enhanced dramatic finale than an embedded part of the movie. It does, however, allow him to make it just about Ali and Emmi again, which is where the film should end up anyway. In spite of this, in his last distortion of the Sirk approach, Fassbinder unleashes a cynicism that is inherent in his work and is probably the source for some of those writing problems I complained about earlier. Rather than a great romantic surge to close out the picture, Fassbinder sticks to something more bittersweet. The lovers may be reunited, but the problems that divided them are incurable and cyclical. The fear can never be fully done away with, and it's always hungry.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder may be in love with the great romantic artistry of Douglas Sirk, but that doesn't mean love is something he can believe in himself. I guess that's the difference between wanting to be Douglas Sirk and actually being him.

Sunday, February 15, 2009

REVANCHE

A slight break from the norm here. Götz Spielmann's film Revanche is being released via Janus Films and Criterion as a first-run theatrical feature (info here). In honor of its Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film (the award is being handed out this coming Sunday) and the recent showings of the movie at the Portland International Film Festival, I thought it might be opportune to review Revanche for this blog.

The tagline for the U.S. release of the Austrian film Revanche (which translates as "revenge") is "Whose fault is it if life doesn't go your way?" For a marketing line, it's a fairly savvy, if somewhat simplistic, distillation of the existential quandary that the various characters in Götz Spielmann's movie find themselves in. At some point, they all want to blame someone else for what has happened, but no one can ever go through with it. The choices they made were their own, and how that affected their lives as well as the lives around them is their own burden to carry.

Revanche begins by showing two seemingly divergent but ultimately connected storylines. On one end of things, we have the troubles of a young couple in the Vienna underworld. Alex (Johannes Krisch) is a hired hand in a brothel, secretly dating the owner's favorite girl (Irina Potapenko). The boss calls her Angel, but her real name is Tamara, and she's an immigrant who has turned to prostitution due to her accumulated debt. Alex is an ex-con with dreams of buying into a bar in Ibiza. If he could get enough money for that, he could get enough to buy out Tamara's debt, as well.

Elsewhere, a young police officer, Robert (Andreas Lust), is trying to climb the ranks of the force that patrols the small village where he lives with his wife, Susanne (Ursula Strauss). They are also trying to start a family, but Susanne's first pregnancy ended in miscarriage, something to which their already finished nursery serves as a painful reminder. The fault isn't with Susanne, though, their problems getting pregnant stem from Robert, who is stressed out at his job. It's performance issues all around for Robert, who is, ironically enough, quick with the trigger on the firing range and also a bit of a coward. Father material? Not really.

Connecting these two couples is Alex's grandfather (Hannes Thanheiser). The old man lives on a farm on property adjoining the country home of Robert and Susanne. It's upon visiting his grandfather and seeing the town he lives near that Alex works out a plan for robbing the small bank there. Tamara is against the idea, she doesn't want Alex going back to jail, but when the crime boss starts putting pressure on her to go full-time as a kept woman for his special clients, it forces Alex's hand. He pulls the job, but it brings the crooks in contact with Robert--and that's when things start to get dicey.

Despite its criminal setting, Revanche isn't really a nail-biter like your average crime thriller; it is, however, that most unique of human dramas, the kind of interpersonal story that moves like a crime picture. By that I mean that it is full of twists and turns that are impossible to predict, especially since Spielmann, who both wrote and directed Revanche, is so good at avoiding telegraphing what choices his subjects will make next. How Robert will react to the bank robbery and how Alex will become intertwined with Susanne are just a couple of the surprising and wholly unexpected story developments. These are characters who make decisions based on the situation at hand, as opposed to following some pre-determined script outline. Thus, Revanche keeps the viewer on the edge of his or her seat regardless of the level of danger in the plot.

Revanche was shot entirely on location, and there is grainy, underlit realism to Martin Gschlacht's cinematography that is both alluring and haunting. In terms of style, Revanche calls to mind other Eastern European movies of recent memory, most specifically 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days . They inhabit the same cold, unforgiving space where each individual is left to survive by whatever means available. Only tough choices are available because it's a tough world.

. They inhabit the same cold, unforgiving space where each individual is left to survive by whatever means available. Only tough choices are available because it's a tough world.

All of the acting in Revanche is of excellent quality, but Johannes Krisch most distinguishes himself with his largely interior, fiery turn as Alex. A criminal by circumstance rather than natural demeanor, he has a false tough guy exterior that careful observers see is outweighed by a stronger moral code. The head of the bordello sees his weakness, and an impulsive act of chivalry on Tamara's behalf is what ultimately proves to make their situation in Vienna untenable. He may be willing to rob a bank, but he does so with an empty pistol, lest someone get hurt; likewise, there may be friction between him and his grandfather, but Alex's extended stay brings out a familial love that both men are reluctant to express, suggesting that playing one's emotional cards close to the vest is a family trait. Susanne even asks Alex what happened to him to make him so hardened, a question to which he has no answer.

In the end, all of the players in this drama will have to come to terms with what they have done or else they will never move forward. Robert stands as the lone holdout, refusing to accept his role in unfortunate circumstances, choosing instead to try to make himself the victim of those same circumstances. As a result, he is the most tortured, whereas the others come to grips with the fact that they are agents of fate in their own lives. Decisions made are decisions that one must stand by, regardless of how harsh the consequences. Everyone has their secrets, too, and shared knowledge cancels them out. What you know about another is only valuable when that other doesn't know anything about you. Maintaining one's own peace is often as simple as living and letting live--and, as is often said, that is the best revenge.

The tagline for the U.S. release of the Austrian film Revanche (which translates as "revenge") is "Whose fault is it if life doesn't go your way?" For a marketing line, it's a fairly savvy, if somewhat simplistic, distillation of the existential quandary that the various characters in Götz Spielmann's movie find themselves in. At some point, they all want to blame someone else for what has happened, but no one can ever go through with it. The choices they made were their own, and how that affected their lives as well as the lives around them is their own burden to carry.

Revanche begins by showing two seemingly divergent but ultimately connected storylines. On one end of things, we have the troubles of a young couple in the Vienna underworld. Alex (Johannes Krisch) is a hired hand in a brothel, secretly dating the owner's favorite girl (Irina Potapenko). The boss calls her Angel, but her real name is Tamara, and she's an immigrant who has turned to prostitution due to her accumulated debt. Alex is an ex-con with dreams of buying into a bar in Ibiza. If he could get enough money for that, he could get enough to buy out Tamara's debt, as well.

Elsewhere, a young police officer, Robert (Andreas Lust), is trying to climb the ranks of the force that patrols the small village where he lives with his wife, Susanne (Ursula Strauss). They are also trying to start a family, but Susanne's first pregnancy ended in miscarriage, something to which their already finished nursery serves as a painful reminder. The fault isn't with Susanne, though, their problems getting pregnant stem from Robert, who is stressed out at his job. It's performance issues all around for Robert, who is, ironically enough, quick with the trigger on the firing range and also a bit of a coward. Father material? Not really.

Connecting these two couples is Alex's grandfather (Hannes Thanheiser). The old man lives on a farm on property adjoining the country home of Robert and Susanne. It's upon visiting his grandfather and seeing the town he lives near that Alex works out a plan for robbing the small bank there. Tamara is against the idea, she doesn't want Alex going back to jail, but when the crime boss starts putting pressure on her to go full-time as a kept woman for his special clients, it forces Alex's hand. He pulls the job, but it brings the crooks in contact with Robert--and that's when things start to get dicey.

Despite its criminal setting, Revanche isn't really a nail-biter like your average crime thriller; it is, however, that most unique of human dramas, the kind of interpersonal story that moves like a crime picture. By that I mean that it is full of twists and turns that are impossible to predict, especially since Spielmann, who both wrote and directed Revanche, is so good at avoiding telegraphing what choices his subjects will make next. How Robert will react to the bank robbery and how Alex will become intertwined with Susanne are just a couple of the surprising and wholly unexpected story developments. These are characters who make decisions based on the situation at hand, as opposed to following some pre-determined script outline. Thus, Revanche keeps the viewer on the edge of his or her seat regardless of the level of danger in the plot.

Revanche was shot entirely on location, and there is grainy, underlit realism to Martin Gschlacht's cinematography that is both alluring and haunting. In terms of style, Revanche calls to mind other Eastern European movies of recent memory, most specifically 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days

All of the acting in Revanche is of excellent quality, but Johannes Krisch most distinguishes himself with his largely interior, fiery turn as Alex. A criminal by circumstance rather than natural demeanor, he has a false tough guy exterior that careful observers see is outweighed by a stronger moral code. The head of the bordello sees his weakness, and an impulsive act of chivalry on Tamara's behalf is what ultimately proves to make their situation in Vienna untenable. He may be willing to rob a bank, but he does so with an empty pistol, lest someone get hurt; likewise, there may be friction between him and his grandfather, but Alex's extended stay brings out a familial love that both men are reluctant to express, suggesting that playing one's emotional cards close to the vest is a family trait. Susanne even asks Alex what happened to him to make him so hardened, a question to which he has no answer.

In the end, all of the players in this drama will have to come to terms with what they have done or else they will never move forward. Robert stands as the lone holdout, refusing to accept his role in unfortunate circumstances, choosing instead to try to make himself the victim of those same circumstances. As a result, he is the most tortured, whereas the others come to grips with the fact that they are agents of fate in their own lives. Decisions made are decisions that one must stand by, regardless of how harsh the consequences. Everyone has their secrets, too, and shared knowledge cancels them out. What you know about another is only valuable when that other doesn't know anything about you. Maintaining one's own peace is often as simple as living and letting live--and, as is often said, that is the best revenge.

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

HOBSON'S CHOICE - #461

Given that David Lean's career is largely characterized by epics like Lawrence of Arabia

Such is the case with his 1954 comedy, Hobson's Choice, a clever tale set in the middle streets of 19th-century Manchester, somewhere between the slums and the commercial center of town. The Hobson of the title is Henry Hobson, a widower father of three and owner of a shoe shop, and played by the legendary actor Charles Laughton. The story--filmed from a screenplay by Lean, Norman Spencer, and Wynyard Browne and based on a stage production by Harold Brighouse--joins Hobson later in life. His business is moderately successful, enough so that he can leave its running to his three daughters while he spends most of the day in his cups down at the Moonraker Pub. The younger daughters (Daphne Anderson and Prunella Scales) have sweethearts and are looking to get married, but their cheapskate father doesn't want to pay the dowry it would require. He also doesn't want his older daughter, Maggie (Brenda De Banzie), to find a husband because then he'd lose the free labor. Though she’s only aged 30, Hobson has already cast Maggie as the old maid, blind to the fact that the responsibility he has put on her all these years has prepared her for life far better than he could have hoped for.

Working in Hobson's shop is one William Mossop (John Mills), a meek cobbler with a special knack for molding leather. Seeing her opportunity after a rich patron (Helen Haye) praises Will's work, Maggie bullies him through a courtship and into business and marriage. They set up a rival shop, wounding poor Hobson's pride and enflaming his bluster. Maggie's scheming extends further, and she arranges her sisters' marriages, turns Will into a man, and brings it all back around to her pop in seemingly short order. The comedy is sweet and never mean-spirited, meaning Maggie's plans work out for everyone, even Henry Hobson gets to save face and retain a little ego. The structure and the presentation have a classical feel, keeping the same basic set-up as was likely found in Brighouse's play, with the various story points coming out of character behavior as much as they are there to service the plot.

In truth, Henry Hobson is a little like a bumbling King Lear, lost in the dementia of drink and unable to see which daughter truly cares for his well-being. Though the story as much belongs to Will and Maggie on paper, on celluloid, Charles Laughton takes full command of the scene. He tears up the screen whenever Hobson goes off on one of his many puffed-up rants, and the actor is skilled enough to convey the force of the tirade while also maintaining the impotence that lays the foundation for Henry's overcompensation. One of the best scenes is when a clearly bruised Hobson, being ribbed by his friends, drunkenly retaliates with bitter insults, exposing an awareness that his position as the patriarch has been undermined. Until Maggie's revolt, he had at least been able to keep up the image of being in charge when sat in the barstool, but now all of that is gone. This scene then makes way for the best bit of comedy in the movie: Charles Laughton, soaked through and through with whiskey, chasing the moon through rain puddles. I've seen a lot of comic drunks in my time (and even been one myself more times than I can count), and this performance is up there with the best. It's utterly convincing, both hysterical and heartbreaking, and laying the groundwork for the sympathy the character will require in the film's final act.

In addition to the charm of the story, Hobson's Choice has the bonus value of being full of wonderful set pieces and impressive location shooting. From the stone streets outside of Hobson's shop to the open parks and the lovers' view of the River Tame, David Lean expertly uses a combination of real environments and detailed sets to recreate a vibrant Victorian city (IMDB indicates that the film was shot both in the Salford suburb of Manchester and in Shepperton Studios). There is no obvious delineation between what may be authentic and what may have been built by a movie crew. The interiors are just as convincing and lively as the exteriors. The art direction of Wilfred Shingleton (Tunes of Glory) is lit with a smart eye for light and shade by regular Lean cameraman Jack Hildyard, creating an inclusive world that fully immerses the viewer in the filmic illusion.

This commitment to realism when combined with the quality of acting gives Hobson's Choice an unexpected air of truth even when the generally smart writing delivers some of its most contrived narrative twists. As with any great family comedy, the audience feels that they are part of the Hobson clan by the end, and thus when just about everyone comes together and gets what is best for them in the finish, it has an added punch of joyfulness. Through the rough stuff (Hobson's morning-after DTs), through the romantic stuff (Maggie and Will's patient acquiescence blossoming into love), and even through the subtle suggestions of class issues (Will's upward mobility, the family's snobbery in his direction), Lean delivers a message that it's both the good and the bad that binds family together, and faith tempered with obstinacy and even a little self-sufficiency will make any obstacle surmountable. Of the many choices that Hobson must make, it's the most important one: to let family do for him what may be best for all rather than simply what he thinks is best for numero uno. It's a quiet transformation, made partially under protest and through gritted teeth, but when it comes to Henry Hobson, one couldn't imagine it going any other way.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

Tuesday, February 3, 2009

SIMON OF THE DESERT - #460

Luis Bunuel's 1965 short film Simon of the Desert may be one of the master surrealist's more straightforward efforts--or, at least, it should be straightforward enough to anyone raised with regular doses of Sunday School. The church I grew up in didn't believe in saints, but the temptations that Bunuel's Simon, whom he based on the story of Saint Simeon Stylites, will look familiar to anyone who has heard the

tale of Jesus being tempted by Satan in the desert.

Simon (Claudio Brook) is a Christian ascetic who has been living atop a literal pedestal of religion for six years, six months, and six days. This life of denial and penitence, undertaken in the middle of a scorched desert, will prove his devotion to God and bring him closer to Heaven. Believers flock around him, other holy men revere him, and Simon shares the lessons he's learned with them all. As the film opens, a grateful patron is moving Simon from his simple pedestal to a fancier, taller tower that has been erected in his honor--an earthly reward for his persistent pursuit of divinity.

Perhaps it is the acceptance of this gift, or perhaps it's the auspicious and evil number inlaid in the duration of Simon's meditation, but the devil has now come to the desert to try to lure Simon down from his place of worship. The trickster appears as a woman (Silvia Pinal), first as a naughty schoolgirl and then in the guise of Jesus Himself. Satan also takes possession of a jealous priest to try to shake the people's belief in Simon through lies. These efforts fail, only giving the target more strength: Simon makes his vigil tougher, swearing to stand on only one leg.

For a notorious prankster who often had a laugh at the expense of organized faith, Bunuel portrays Simon's spiritual mission with the utmost respect. He still can't resist having a go at the false worshippers and dishonest holy men, however, showing how the gathered take advantage of Simon's miracles and how many priests are only coming to give tribute for the sake of appearances. In Bunuel's philosophy, the phony far outnumber the authentic.

And we do see that Simon is authentic because we see his temptations and his renunciation of the same. This doesn't just include the ones brought forth by Satan--though those are brought to life with showmanship and rather good special effects--but also the ones that creep into Simon's mind via normal trains of thought. Like Scorsese's portrait of Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ, Simon sees himself in more normal surroundings, accepting love and family as his own, but he banishes such thoughts from his mind in affirmation of his faith.

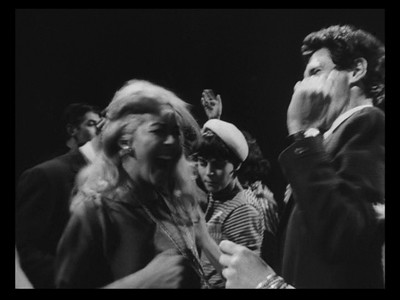

There is only one thing that Simon cannot stand up against, and it is Satan's final gambit. Arguably, the sin of pride could also be Simon's downfall, with how zealously he challenges the devil to unload the full arsenal, but this is what the fallen one is relying on. In a Twilight Zone-worthy twist, the Devil transports Simon to a future city. Looking now like an existentially weary beatnik, Simon sits with the beautiful arc angel at a table in a rock 'n' roll club. When Simon finds nothing of interest in the bawdy decadence and demands to be returned home to his pedestal, Satan tells him that it is too late, that he has already been replaced--the implication being that he has not been replaced by another ascetic, but by modern life, by a society that rejects the oppressiveness of religion for the freedom of music and technology. Satan joins in the dance, laughing, leaving Simon alone in his 20th-century despair.

Ah, there's the rub! Here is where Bunuel lies in wait to needle the religious rank and file. In the closing sequence of Simon of the Desert, which spends a long time amongst the kids dancing before moving over to the bored looking Simon, thus letting us know how fun it is on the dancefloor, Bunuel is getting the last laugh, fulfilled for him in the bright and lovely smile of Silvia Pinal. “You may have been right,” he seems to say to Simon, “but what good has it done you? The other side won anyway.”

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

Sunday, February 1, 2009

SIDELINE: MORE REVIEWS FOR 01/09

In addition to my Criterion reviews, here are other reviews film fans of similar tastes might find of interest from the last month:

IN THEATRES...

* Ciao, a lo-fi drama about love and grief

* The Class, fact and fiction collide in this French film about an inner-city school.

ON DVD...

* Being There: Deluxe Edition, the classic comedic fable from Jerzy Kosinski, Hal Ashby, and Peter Sellers. Delightful!

* Funny Face - The Centennial Collection, a new release of an old Audrey Hepburn favorite. Goes well with Audrey Hepburn Remembered

* Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, a meticulous look at the sex scandal that caused the revered director to flee the U.S. Very fascinating stuff.

IN THEATRES...

* Ciao, a lo-fi drama about love and grief

* The Class, fact and fiction collide in this French film about an inner-city school.

ON DVD...

* Being There: Deluxe Edition, the classic comedic fable from Jerzy Kosinski, Hal Ashby, and Peter Sellers. Delightful!

* Funny Face - The Centennial Collection, a new release of an old Audrey Hepburn favorite. Goes well with Audrey Hepburn Remembered

* Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, a meticulous look at the sex scandal that caused the revered director to flee the U.S. Very fascinating stuff.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)