I think it best that I make it official up front: I am not really a fan of Nicolas Roeg. This has altogether been confirmed upon my second viewing of The Man Who Fell to Earth, which is easily my least favorite of the handful of movies I've seen from the director. I first watched it eight or more years ago when I had the Anchor Bay DVD, and I recall not caring for it much, but I thought enough time had passed to give it another shot. Plus, this time I'd be seeing it in a theater, and being a different time and a different environment, you never know. Maybe I could get into The Man Who Fell to Earth. Changing one's place in the temporal and physical universe is certainly in keeping with the nature of Roeg's work, regardless.

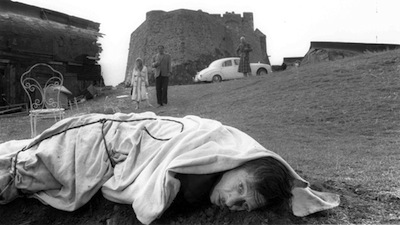

Suffice to say, things did not go as planned. Being trapped in my seat for 139 minutes just made The Man Who Fell to Earth all the more excruciating. The story itself covers 40 or 50 years, which is how long it felt like while I was viewing it. Funny, though, as much as the characters age, the world doesn't change. Is The Man Who Fell to Earth a science fiction movie or a horror flick where the 1970s never end?

The main appeal of The Man Who Fell to Earth for me, then and now, is David Bowie. I am a fan, and this film seemed like the perfect vehicle for the rock legend. In fact, Roeg is banking on and toying with the singer's image in the movie. This story of a displaced genius from outer space--written by Paul Mayersberg from a novel by Walter Tevis--has parallels with Bowie's own rise, the resulting problems, and the eventual experimentation and reinvention. His flaming hair is the same shade of orange he famously wore as Ziggy Stardust, the stage persona he invented in the early 1970s. He is the star brought low--by his fame, his addictions, and a public that both adores and misunderstands what he is offering.

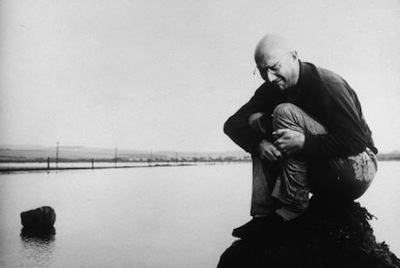

In the movie, Bowie plays Thomas Jerome Newton, a.k.a. Mr. Sussex, an inventor and entrepreneur whose globe-spanning corporation World Enterprises revolutionizes the modern world and how it interacts with technology and art. Or so we can surmise. Roeg is not concerned with such fussy details, the business end of things is more of a devise to establish Newton's primary mission. He is not a British ex-pat as his passport suggests, but an alien from another planet come to Earth in search of water. His homeworld is suffering a terrible drought. Only, now he is stranded, and he is using World Enterprises--abbreviated as WE, because, you know, he is us--as a platform to build a spaceship to get him back to his wife and kids.

Newton amasses his fortune, aided by an opportunistic patent lawyer (Buck Henry in ludicrously thick glasses) and eventually a chemist (Rip Torn) who feels drawn to Newton's work despite of, or perhaps because of, its being cloaked in secrecy. As the years pass, however, Newton gets sucked into life on Earth. He moves to New Mexico and experiences America the Surreal, an antiquated landscape of dilapidated carnivals, rundown motels, and shit-kicking cops. He watches television to soak up knowledge, test drives religion, and eventually tries on domesticity, settling into a long-term relationship with alcoholic hotel maid Mary Lou (Candy Clark). She gets him hooked on gin, and when he drinks, Newton has visions of home and can peer through time to see the original frontiersmen. Who can also see him. So how is that a hallucination exactly?

It may be silly to question the logic of a psychedelic free-for-all such as this, but I'd submit that's exactly the false apology that has allowed The Man Who Fell to Earth to garner its revered reputation. Nicolas Roeg's films suffer from the dual sins of "anything goes" and "good enough." No left turn is too sharp for him to take over the course of a narrative, yet he is also not patient enough to follow these impulses through. Many of the scenes in The Man Who Fell to Earth don't connect well with the scenes that surround them, and the film overall is visually sloppy. Roeg strikes me as a petulant adolescent who refuses to shave, much less comb his hair, because this is the style, man. The Man Who Fell to Earth presents an ugly, slapdash future, one that is as regressive as it is forward thinking. This may be part of the point--how else do you explain Rip Torn going to a record shop and buying vinyl even after David Bowie has introduced sound crystals to the world?--but Roeg never really sews any of it together. The clarity of his montage is regularly interrupted by indulgent auditions for future David Bowie album covers. Well, congratulations, sir, you managed to score two. (Low

Sadly, good performers flounder under Roeg's direction. Buck Henry and Rip Torn are both okay, but they have both also done better. Sometimes a take is so clumsy, one might almost guess it's just the first one where the actors managed to finish without flubbing their lines. Bowie seems lost through most of it, and his clothes from sequence to sequence appear to match whatever phase he was going through at the time. (Mainly, the Thin White Duke alias adopted for Young Americans

The only one who comes through looking her best is Candy Clark. Her motor-mouthed plain jane is right on the money, capturing the sort of shallow American figure that is more than willing to latch on to the empty dreams of others. The Mary Lou character is more complex than that, though, she seems less interested in what Newton can offer her than she is in taking care of him. Theirs is ultimately a co-dependent relationship, neither being good for the other, yet refusing to break it off. Even laboring under bad old-person make-up, Clark is able to inspire pity for Mary Lou. She is a well-meaning girl who is beyond her depth.

To be fair, there is much in The Man Who Fell to Earth's underlying political message that is extremely prescient. Media saturation, corporate dominance, a dangerous mistrust of new ideas--these are all issues that would become increasingly important since the movie's release in 1976. There is even a scene later in the film where a worker in the control room for a space launch ponders the needless expense laid out for space travel. Why spend money on exploring the cosmos, who cares? The only element of The Man Who Fell to Earth that seems politically regressive is Roeg's casting African American-actor Bernie Casey as the big-business government thug who takes Newton down. While putting a black man in a position of power, and making him the husband in a bi-racial marriage, was likely a daring move back then, Roeg's staging of Casey's scenes has caused this aspect of the film to age poorly. Instead of seeming progressive or even just normal, it comes off now as white fear that the black man is coming for his money and his women. Again, not Roeg's intention, but contexts change as decades pass.

I am sure my opinions about The Man Who Fell to Earth are going to be unpopular; my previous disappointment in Nicolas Roeg movies has usually garnered many clucking tongues and even harsher replies, no matter how open I've tried to be to the experience. (The one Roeg film I genuinely like is Performance; you can read my review here.) That's fine enough, I see Roeg as a provocateur who would likely relish such healthy debate. I also get that many delight in the head trip that midnight movies of this kind offer--though, if I want to see the David Bowie story turned into parable and fairy tale, I much prefer Todd Haynes' Velvet Goldmine

For those who might still be down for such an experience, it's worth noting that both the standard edition and the Criterion Blu-ray