IN THEATRES...

* Amelia, Mira Nair's biopic of Amelia Earhart is an emotionless snoozer. Starring Hilary Swank.

* Antichrist, the new Lars von Trier philosophical shocker is one of the most unsettling movies I have ever seen. Not for the faint of heart or the quick to judge.

* Astro Boy, a cool looking movie that is stuck somewhere between the quality of the original material and a misguided desire to satisfy the kiddie market.

* Coco Before Chanel, starring Audrey Tautou as the fashion designer in her formative years.

* A Serious Man, the new Coen Bros. mind blower. I know everyone has seen the trailer, but I am including it above just because it's one of the best ever. And best of all? It tells you NOTHING!

* No Impact Man, a documentary about Colin Beavan and his family, who tried an experiment of living off only sustainable resources for a full year.

* Where the Wild Things Are will make you believe in the impossible in every way.

ON DVD...

* Actors & Sin, a slick entertainment-themed double-bill from Ben Hecht.

* British Cinema: Renown Pictures Crime & Noir (Blackout, Bond of Fear, Home To Danger, Meet Mr. Callaghan, No Trace, Recoil), collecting six films from the 1950s, none of them very good.

* Luis Bunuel's Death in the Garden, a 1950s potboiler from the surrealist director's Mexican period.

* Diary for My Children (Napio gyermekeimnek), a 1984 film from Hungarian writer/director Márta Mészáros is a personal portrait that is maybe too personal to effectively communicate its tale.

* Il Divo, a flashy Italian biopic of politician Giulio Andreotti.

* Fados, Carlos Saura's performance documentary on a particular style of songcraft from Portugal. Lots of songs, very little information.

* Lightning Strikes Twice, King Vidor's mild melodrama about women who fall for the wrong men.

* Management, in which Steve Zahn stalks Jennifer Aniston and they call it a "romantic comedy." Both terms are almost entirely wrong, though there are glimmers of quality.

* My Fair Lady, the Audrey Hepburn musical is reissued and downgraded. Keep your old DVDs, they are better.

* Whatever Works, the Woody Allen/Larry David movie comes to DVD, and I revisit my old review from its theatrical run.

Saturday, October 31, 2009

Thursday, October 29, 2009

WINGS OF DESIRE - #490

"There is no greater story than ours, that of man and woman. It will be a story of giants...invisible...transferable. A story of new ancestors."

I still remember seeing Wings of Desire the first time. I had heard about it from watching Siskel & Ebert, and knew vaguely that it was the same filmmaker who was responsible for Until the End of the World, which I had not seen either, but I obsessively listened to the soundtrack, which I had purchased for the new Depeche Mode track. Just as that CD had introduced me to a bunch of bands I didn't really know, expanding my musical horizons (Elvis Costello covering the Kinks was like a double-shot of "What's this good stuff?"), Wings of Desire would be important to my understanding of experimental narratives and cinema as art. If nothing else, it made foreign films that didn't have samurais in them a little less scary.

I only begin this way--the first two paragraphs in a movie review shouldn't really lead with a first-person pronoun--because I think Wings of Desire is a "Where were you when?" film. Where were you when you first saw it? Who showed it to you? Who were you? Up until a couple of days ago I had forgotten, for instance, that I had given the previous DVD edition to one of my best movie pals several years ago. He had never seen it before that. Wings of Desire is just that kind of film. Once you've seen it, you don't keep it to yourself. (And you certainly stop anyone you can from seeing the remake. Friends don't let friends watch City of Angels.)

Released in 1987, Wings of Desire is the brainchild of German writer/director Wim Wenders. The filmmaker was at the zenith of his creative powers in this period, with Wings being in the middle of his three best fictional films, sandwiched between Paris, Texas and the aforementioned Until the End of the World. (Seriously, when the hell are we going to get a DVD of that?!) That's some esteemed company, but even amidst those films, Wings of Desire is still the best, the uppermost tip of Wenders' artistic spear.

That's because Wings of Desire is the film that could not be made by anyone else, that could not be made at any other time. This was two years prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall, and I think that fact alone would have changed the tenor of Wenders' masterpiece. Though there is very little mention of the political situation in Berlin at the time, the separation that city felt was very much a part of the subtext. Wings of Desire is about a world divided, about the line between the spiritual and the physical, the fanciful and the practical. Between the poetry of words and thought and the true poetry of life.

Bruno Ganz stars as Damiel, one of an army of angels assigned to Berlin. In this reality, angels act not as guardians, but as witnesses. They wander through our lives, silent and invisible, observing our activities and eavesdropping on our thoughts. They might follow one person in specific, or they might roam through a crowd, sampling a little something from each. There are wonderful scenes on a plane or in the public library where the sound mixers scroll through the gathered people, moving from one inner monologue to another the way we flip through channels with our TV remote. In the library, there are almost as many angels as there are mortals, all looking for something interesting to commit to memory or maybe scribble down in one of their little notebooks.

Damiel shares just such discoveries with his best friend Cassiel (Otto Sander). After centuries of observing the human race, they are still capable of being charmed by our irrational behavior. Just reporting that he saw a woman close her umbrella and allow herself to be drenched in a downpour brings a smile to Damiel's face. What unpredictable creatures! What must they feel? How do things taste? What's it like to really hold something in your hand? The angels can take objects from us, but they are merely copies and not tangible. It's not the same.

Call it divine existentialism. Our earthly version of that philosophy ponders what it must be like to transcend the physical and join the divine; for an angel, the crisis of identity involves shedding your wings and eternity and becoming flesh. Damiel has grown tired of watching, he wants to start doing things. The final catalyst for "taking the plunge," the human idiom for what is essentially a fall from grace, is a beautiful trapeze artist, Marion (Solveig Dommartin), that the angel has become smitten with. She is his human analogue, soaring above the ground as she does, even wearing a pair of feathery wings. Marion dreams of flying, Damiel dreams of walking--opposites, prepare to attract!

The transformation from heavenly to earthly creature thankfully comes in the final third of the film. Had it come sooner, it would have made for a much cheaper experience. There is nothing wrong with the end of the film, it's actually quite perfect, and Bruno Ganz is at his most compelling as the excited new human rushing through Berlin, seeking every sensation, tasting his first cup of coffee and learning to whistle. His childlike exuberance is infectious. The romantic meeting is also splendid, with Wenders and co-writer Peter Handke avoiding the triteness of love story coincidences by properly joining the fates of Damiel and Marion early on. Though angels can't directly influence a human, they can make their presence felt, and Damiel's constant hanging around lends Marion peace while assuring that he will be familiar to her when they meet face to face. (At a Nick Cave concert no less. Some vintage footage here!)

The romance is sort of the cherry on top, and the rest of the movie is the true sundae. It's the build-up, the gathering together and the exploration of this world. Wenders takes us on a tour through the city, showing us people from all walks of life. Under his gaze, living is a lyrical happening. One of Cassiel's favorite people, an old poet named Homer (Curt Bois, who had acted in his first movie eighty years before Wings), asks why no epic ballads have ever been written in tribute to peace the way they have been about war. This would seem to be a personal challenge that Wenders has made to himself and buried within the movie proper. What Cassiel and Damiel observe is like a visual song celebrating an everyday peace. It's not all happy--there is suicide, bills to pay, drug addiction--but there is a nobility to forging ahead, to making your own personal story even if no author is ever going to write it down. It's easy for the angels, they pass through everything unharmed; humans have the ability to touch and be touched in turn. Divinity has its purpose, but as Peter Falk, playing himself as a former angel, informs Damiel, there is nothing to compare to the sensations of the finite.

Falk's role also connects the film to history. He's come to Berlin to make a movie about a private detective in WWII, and extras stand around on the set wearing Nazi uniforms and clothes marked with the Star of David. The past is alive and well within the city, and old newsreel footage is cut into Wings of Desire, seen from car windows, the ghost of memory. It's another division between realms, one of many in the movie. Wim Wenders and cinematographer Henri Alekan (Topkapi), along with assistant director Claire Denis, create a vivid visual division between the heavenly and the earthly. The angels and what they see are shot in crisp, cool black-and-white (restored here to a more silvery hue rather than the gold of previous DVDs) while the mortal experience is shown to us in full color, rich in tone and often garish. Humanity experiences the full spectrum, whereas the angels' vision is limited. For all of their peeping in on our brains, the angels are confined. They can't do anything else. This is the core of existentialism: choice is what makes us free. Our imperfections define us. The brightest light burns half as long.

For all these happenings, Wings of Desire actually ends on a downbeat. Though Damiel has found love and joy with Marion, Cassiel is now alone in the heavenly realm, watching his friend's new life without anyone to talk about it with. His divine plight is one of loneliness, but as the final words of Homer and the "to be continued" card that precedes the credits tell us, this is only the beginning of the story. Like an acorn falling from a tree, Damiel is only the first. The sequel, Faraway, So Close! , was several years off, and I don't recall it having the same impact. Maybe it was best to leave well enough alone. Somehow the suggestion that maybe Cassiel will follow Damiel's example is more effective than him actually doing so. It's probably because it allows us all to be Cassiel, looking to a more hopeful future all our own. The follow-up story itself ends up being too specific, and thus not satisfying.

, was several years off, and I don't recall it having the same impact. Maybe it was best to leave well enough alone. Somehow the suggestion that maybe Cassiel will follow Damiel's example is more effective than him actually doing so. It's probably because it allows us all to be Cassiel, looking to a more hopeful future all our own. The follow-up story itself ends up being too specific, and thus not satisfying.

I don't recall movies from the same period being nearly as hopeful as Wings of Desire. Not without resorting to treacle. Wim Wenders manages to avoid the schmaltz. Wings of Desire is the work of an artist who can see a better world on the horizon and is using his art to reach out for it, to pull it closer. His message remains in the abstract, but it's no less effective for not being spelled out. That angelic power of observance, the god's eye view afforded by the camera, equalizes all life in our vision, let's us find ourselves within it, and forever changes how we see things in the process. Or at least that's how it was for me. How about you?

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

I still remember seeing Wings of Desire the first time. I had heard about it from watching Siskel & Ebert, and knew vaguely that it was the same filmmaker who was responsible for Until the End of the World, which I had not seen either, but I obsessively listened to the soundtrack, which I had purchased for the new Depeche Mode track. Just as that CD had introduced me to a bunch of bands I didn't really know, expanding my musical horizons (Elvis Costello covering the Kinks was like a double-shot of "What's this good stuff?"), Wings of Desire would be important to my understanding of experimental narratives and cinema as art. If nothing else, it made foreign films that didn't have samurais in them a little less scary.

I only begin this way--the first two paragraphs in a movie review shouldn't really lead with a first-person pronoun--because I think Wings of Desire is a "Where were you when?" film. Where were you when you first saw it? Who showed it to you? Who were you? Up until a couple of days ago I had forgotten, for instance, that I had given the previous DVD edition to one of my best movie pals several years ago. He had never seen it before that. Wings of Desire is just that kind of film. Once you've seen it, you don't keep it to yourself. (And you certainly stop anyone you can from seeing the remake. Friends don't let friends watch City of Angels.)

Released in 1987, Wings of Desire is the brainchild of German writer/director Wim Wenders. The filmmaker was at the zenith of his creative powers in this period, with Wings being in the middle of his three best fictional films, sandwiched between Paris, Texas and the aforementioned Until the End of the World. (Seriously, when the hell are we going to get a DVD of that?!) That's some esteemed company, but even amidst those films, Wings of Desire is still the best, the uppermost tip of Wenders' artistic spear.

That's because Wings of Desire is the film that could not be made by anyone else, that could not be made at any other time. This was two years prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall, and I think that fact alone would have changed the tenor of Wenders' masterpiece. Though there is very little mention of the political situation in Berlin at the time, the separation that city felt was very much a part of the subtext. Wings of Desire is about a world divided, about the line between the spiritual and the physical, the fanciful and the practical. Between the poetry of words and thought and the true poetry of life.

Bruno Ganz stars as Damiel, one of an army of angels assigned to Berlin. In this reality, angels act not as guardians, but as witnesses. They wander through our lives, silent and invisible, observing our activities and eavesdropping on our thoughts. They might follow one person in specific, or they might roam through a crowd, sampling a little something from each. There are wonderful scenes on a plane or in the public library where the sound mixers scroll through the gathered people, moving from one inner monologue to another the way we flip through channels with our TV remote. In the library, there are almost as many angels as there are mortals, all looking for something interesting to commit to memory or maybe scribble down in one of their little notebooks.

Damiel shares just such discoveries with his best friend Cassiel (Otto Sander). After centuries of observing the human race, they are still capable of being charmed by our irrational behavior. Just reporting that he saw a woman close her umbrella and allow herself to be drenched in a downpour brings a smile to Damiel's face. What unpredictable creatures! What must they feel? How do things taste? What's it like to really hold something in your hand? The angels can take objects from us, but they are merely copies and not tangible. It's not the same.

Call it divine existentialism. Our earthly version of that philosophy ponders what it must be like to transcend the physical and join the divine; for an angel, the crisis of identity involves shedding your wings and eternity and becoming flesh. Damiel has grown tired of watching, he wants to start doing things. The final catalyst for "taking the plunge," the human idiom for what is essentially a fall from grace, is a beautiful trapeze artist, Marion (Solveig Dommartin), that the angel has become smitten with. She is his human analogue, soaring above the ground as she does, even wearing a pair of feathery wings. Marion dreams of flying, Damiel dreams of walking--opposites, prepare to attract!

The transformation from heavenly to earthly creature thankfully comes in the final third of the film. Had it come sooner, it would have made for a much cheaper experience. There is nothing wrong with the end of the film, it's actually quite perfect, and Bruno Ganz is at his most compelling as the excited new human rushing through Berlin, seeking every sensation, tasting his first cup of coffee and learning to whistle. His childlike exuberance is infectious. The romantic meeting is also splendid, with Wenders and co-writer Peter Handke avoiding the triteness of love story coincidences by properly joining the fates of Damiel and Marion early on. Though angels can't directly influence a human, they can make their presence felt, and Damiel's constant hanging around lends Marion peace while assuring that he will be familiar to her when they meet face to face. (At a Nick Cave concert no less. Some vintage footage here!)

The romance is sort of the cherry on top, and the rest of the movie is the true sundae. It's the build-up, the gathering together and the exploration of this world. Wenders takes us on a tour through the city, showing us people from all walks of life. Under his gaze, living is a lyrical happening. One of Cassiel's favorite people, an old poet named Homer (Curt Bois, who had acted in his first movie eighty years before Wings), asks why no epic ballads have ever been written in tribute to peace the way they have been about war. This would seem to be a personal challenge that Wenders has made to himself and buried within the movie proper. What Cassiel and Damiel observe is like a visual song celebrating an everyday peace. It's not all happy--there is suicide, bills to pay, drug addiction--but there is a nobility to forging ahead, to making your own personal story even if no author is ever going to write it down. It's easy for the angels, they pass through everything unharmed; humans have the ability to touch and be touched in turn. Divinity has its purpose, but as Peter Falk, playing himself as a former angel, informs Damiel, there is nothing to compare to the sensations of the finite.

Wim Wenders and Peter Falk

Falk's role also connects the film to history. He's come to Berlin to make a movie about a private detective in WWII, and extras stand around on the set wearing Nazi uniforms and clothes marked with the Star of David. The past is alive and well within the city, and old newsreel footage is cut into Wings of Desire, seen from car windows, the ghost of memory. It's another division between realms, one of many in the movie. Wim Wenders and cinematographer Henri Alekan (Topkapi), along with assistant director Claire Denis, create a vivid visual division between the heavenly and the earthly. The angels and what they see are shot in crisp, cool black-and-white (restored here to a more silvery hue rather than the gold of previous DVDs) while the mortal experience is shown to us in full color, rich in tone and often garish. Humanity experiences the full spectrum, whereas the angels' vision is limited. For all of their peeping in on our brains, the angels are confined. They can't do anything else. This is the core of existentialism: choice is what makes us free. Our imperfections define us. The brightest light burns half as long.

For all these happenings, Wings of Desire actually ends on a downbeat. Though Damiel has found love and joy with Marion, Cassiel is now alone in the heavenly realm, watching his friend's new life without anyone to talk about it with. His divine plight is one of loneliness, but as the final words of Homer and the "to be continued" card that precedes the credits tell us, this is only the beginning of the story. Like an acorn falling from a tree, Damiel is only the first. The sequel, Faraway, So Close!

I don't recall movies from the same period being nearly as hopeful as Wings of Desire. Not without resorting to treacle. Wim Wenders manages to avoid the schmaltz. Wings of Desire is the work of an artist who can see a better world on the horizon and is using his art to reach out for it, to pull it closer. His message remains in the abstract, but it's no less effective for not being spelled out. That angelic power of observance, the god's eye view afforded by the camera, equalizes all life in our vision, let's us find ourselves within it, and forever changes how we see things in the process. Or at least that's how it was for me. How about you?

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

Saturday, October 24, 2009

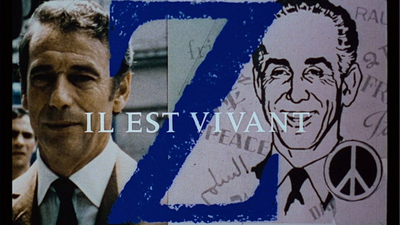

Z - #491

In the 1990s, when the original Rodney King trial went the wrong way despite what to most people was pretty compelling evidence, arguments were made about what we think we see versus what we actually saw. A video of a man being beaten, we were told, was not clear-cut. You see that club there? It's not actually connecting. And it's only one vantage point. You weren't there. How could you know?

Last year, there was a Hollywood movie actually called Vantage Point

While that's not really the point of Costa-Gavras' 1969 political thriller Z, I was struck by how ahead of the curve he was in predicting how placing cameras in different places could show us the same event in different ways. Z is shot a lot like a documentary, an investigative procedural that has aesthetics in common with the Nouvelle Vague and the films of Francesco Rosi, and would in turn inspire Alan J. Pakula, David Fincher, and Steven Soderbergh. Z could almost be seen as a stylistic fulcrum on which the two sides of that equation balance, the link between Salvatore Giuliano and All the President's Men

Written by Costa-Gavras alongside Jorge Semprun and based on a book by Vassilis Vassilikos

The rally is far from peaceful. As the police stand by and watch, there are multiple skirmishes and attacks, the last of which leaves the deputy bleeding in the road. The culprits, Vago and Yago (Marcel Bozzufi and Renato Salvatori), are arrested and their story about being harmless drunk drivers perpetrating an unfortunate hit-and-run is accepted as fact whereas any counter theories are dismissed as Commie propaganda. Only after the deputy dies does an autopsy reveal that his skull fracture is more consistent with a clubbing than with an auto collision. A diligent prosecutor (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and a gutsy reporter (Jacques Perrin) start digging further, and pretty quickly, more inconsistencies in the story begin to show. Connections between Vago and Yago and a right-wing religious group further reveals connections between that group and the chief of police (Pierre Dux) and his right-hand thug (Julien Guiomar). Further attacks on witnesses only fuel the prosecution, as does government opposition.

Costa-Gavras takes us through the investigation step by step. He lines up each piece in their natural order, only taking minor detours into extraneous character stuff (Vago's sexual predilections; the deputy's heartbroken wife, played with stalwart grace by Irene Papas, and even glimpses of their marital strife). Working with renowned cinematographer Raoul Coutard, who shot the bulk of Godard's 1960s films (and who also shows up on the other side of the camera as a British surgeon), he shoots most of the action as if it were a documentary. Coutard's camera is rarely nailed down, but often moving with the flow of activity, acting more as a cold witness than an active part of the story. The fact that we can be everywhere at once creates a kind of hyper-naturalism. Z looks real, but it's not bound by time or space. Flashbacks are common, quick glimpses of memory, and even moments of minor comedy.

When the deputy is struck down, we see it clearly. The truck drives by, Vago leans out and hits the man, and the crowd parts to let them leave. Or is that what happened at all? I don't think that Costa-Gavras means us to really doubt what we saw the first time, but as we see the event as it is described by others, we see how the story of the drunk driving could appear plausible from their field of vision. It also keeps us on our toes, we're never quite sure of who knows what. Even one of the deputy's own people isn't positive the man got clubbed, and when he tells the story, we don't see the fatal blow. We do see the cruel hysteria of the crowd, snippets of the onlookers and enemies circling the victim playing backwards and forwards like we're flipping through snapshots. Costa-Gavras also drops out most of the audio, leaving only the elements the witness relates. It's cinema as point of view, as unreliable and incomplete as that can be. Watching Z, you can start to understand how one can argue about the veracity of a length of videotape.

As Z moves forward, it builds up a head of steam, and the investigation gathers its own momentum. Though the prosecutor doesn't make any grand speeches, he emerges as a heroic figure, committed to fairness and the truth. He is as distrusting of any one side as he is another. Trintignant plays him without any affectation. He's as straight a straight shooter as you're likely to get. On the other hand, there is nothing selfless about the reporter's pursuit of the story, the way he always secretly takes photos even when instructed not to and is aware of the monetary value of the information he's gathering. Perrin is loose limbed and energetic, jumping around and sometimes quite literally chasing the story. These guys are like the European version of Redford and Hoffman.

Interestingly enough, despite the successful exposure of the conspiracy, Z does not end on a hopeful note. Costa-Gavras gives the film a coda where things get worse instead of better. A news broadcast by Perrin informs us of the fate many of the players suffered, and a voiceover and text scroll details a government crackdown that follows, shifting Z out of amped-up Neorealism and into Orwellian sci-fi. It's a far more cynical way to close the movie than, say, Nixon being taken down (to continue the All the President's Men comparison). In this, too, Costa-Gavras is ahead of the game. In the decades that followed Nixon's souring of the American political system, we've often seen those members of his party who succeeded him use unsavory methods to take back the respect Tricky Dick lost them. It's much easier than earning it, and much more effective in demoralizing the public so they won't question the government's methods again. The ending of Z isn't science fiction at all; it's clairvoyant.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

Costa-Gavras

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

MONSOON WEDDING - #489

The first words that appear as Monsoon Wedding goes into the final credits are "For my Family." As far as movie punctuation goes, it couldn't be more perfect. It makes more sense than, say, "The End." Mira Nair's light-hearted drama is about nothing if not about family. It's the sort of work of art that could not be made without knowing all the love, anger, and frustrations that come with the most common of bonds. Sabrina Dhawan's script casts a wide net, pulling in all the distant strands of the Verma clan, with relatives coming in from America, Dubai, Australia and probably all points in between. This is a gathering that reflects the new global culture, and not in some falsified sense of politically correct diversity a la Jonathan Demme's Rachel Getting Married (which, in retrospect, owes a ton to Monsoon Wedding; get me an intellectual property lawyer, stat!). Consider the Verma backyard as the starting point, the paradise where man began, and they've now gone forth and multiplied.

The occasion of the family reunion is an arranged marriage. Aditi Verma (Vasundhara Das), the daughter of Lalit (Naseeruddin Shah) and Pimmi (Lillete Dubey), is to be married to Hemant Rai (Parvis Dabas). The Rais currently call Houston, Texas, their home, and they have returned to India for the grand celebration of a traditional wedding. Lalit is a successful merchant, but he's going into debt up to his eyeballs preparing a lavish four-day festival for his daughter. The wedding planner is a slick hustler named P.K. Dubey (Vijay Raaz), who before the ceremony is over will have found love himself, gaining the hand of one of the servants at the Verma house, Alice (Tillotama Shome). Her anglicized name is a symbol of the Westernization that was occurring all across India, as is the tattoo on the shoulder of one of Aditi's cousins (Neha Dubey) and the way everyone talks in an indistinguishable mix of English and Hindi. Not to mention all the cell phones--though, this is 2001, so they're twice as big as our phones now and just as crappy.

I wasn't all that impressed with Monsoon Wedding the first time I saw it. It seemed silly and cliché, the convenient arrangement of comedy and family drama being too...well, too convenient. Even on second viewing, I still felt much the same way through the first half hour or so. Dhawan's script relies heavily on soap opera. For instance, the bride is having an affair with a talk show host (Sameer Arya), and she has only agreed to the marriage with Hemant because she's convinced her lover will never leave his wife. Her confidant is her older cousin Ria (Shefali Shetty), who has been in Lalit's care since her father died but who has not yet found a husband herself. This is common romance movie stuff.

Except what Mira Nair and Sabrina Dhawan do with this set-up is so much more than that. The matters of the heart that they are going to explore are not confined just to the bride and the groom, nor is it a simple matter of who loves who and who doesn't and why or why not. Amidst all of this chaos are conflicts of old traditions and new, questions of responsibility, family secrets, and even an upstairs/downstairs division between servant and employer. The courtship of Dubey and Alice is one of the more understated and effective aspects of the movie. Dubey turns out to be sweet and intensely romantic, and the contrast between the ostentatious display he designs for the Vermas and the much smaller, much more intimate one he creates just for Alice is beautifully rendered.

Mira Nair is a filmmaker who has always had an eye for lush compositions that she then contrasts with the real world. She likes trying to erect a little perfection within an imperfect setting. Look at her adaptation of Vanity Fair

If Monsoon Wedding were merely a pretty movie, it would be pretty enough to keep watching even without a good script. Luckily, as much attention is paid to the complexities of the characters as it is to the environment they inhabit. Each character gets his or her own story line, and each story line is fully fleshed out so that it is satisfying and contributes to the overall effect. Aditi's struggles with fidelity, Ria's hidden demons, even the tattooed cousin getting her Australian in-law to embrace his Indian heritage, which serves as counterpoint to Aditi moving on to America--all of these intriguing parts form an impressive whole. Again, on paper, this may read like something you've seen before, but Monsoon Wedding is written and performed with such honesty, it proves it's not how original the story but the quality of the execution. The familiarity of the clothes could make you miss how well they are worn the first time you watch the film, the way it did with me, but try it again, you'll start to get it the second time around.

Monsoon Wedding may be overrun with women, but the most memorable character in the movie is the father, Lalit Verma. A proud man, Lalit understands tradition and has hopes for how things should go. Naseeruddin Shah plays him at the edge of nervousness, like at any moment he could collapse from the burden of it all. He is a man of many contradictions, encouraging Ria to go to America and become a writer, a fairly progressive move, but he's rigid when it comes to his son, who likes dancing and cooking and may need to step through a closet door in the near future. Shah has many powerful scenes. He is fierce and noble when declaring his intention to protect his girls, but shockingly brittle when that determination is put to the test--and it's all the more admirable that he stands up given the doubt he must overcome. The scene that really sticks with me, though, is the morning after a startling revelation, when the father figure wakes up crying. Very few words are exchanged, but his wife pulls him into her arms, and we see the true strength at the heart of the Verma family. It's neither one nor the other, mother nor father, husband nor wife, but the two of them together.

With all of these primal emotions swirling around, it's no wonder that the filmmakers would turn to a symbol as primal as the weather to represent them. In the days leading up to the wedding, the weather is as scorching as the drama. By the time the titular monsoon comes to drench the wedding party, it's not a tempestuous explosion a la the madness storm in King Lear but a full-on release. Ironically, Lalit tried to protect his girls from just this kind of downpour, paying Dubey extra for waterproofing. That's how much the man's head had gotten turned in the wrong direction. This rain is exactly what the Vermas needed. Dodging the showers first cause them to huddle together, and then to let loose, to dance without any worry, to forget what might separate them. Even Dubey and Alice are welcomed into the circle. A rainstorm can, yes, be overwhelming and even deadly, but as Monsoon Wedding reminds us, it also cleans, refreshes, and rejuvenates. Wash away the old to make way for the new.

The Monsoon Wedding - Criterion Collection DVD is a 2-disc special edition. The discs are housed in a foldable cardboard book with plastic trays, and it fits in a marigold-colored outer slipcover. The artwork from the opening credits is used to illustrate the box and accompanying booklet, linking the packaging to the movie in a smart, classy manner. The book has lovely photographs, an essay by author Pico Iyer, credits, chapter listing, a glimpse at a special piece of production art, and a guide to the bonus films on DVD 2.

For some reason, one of the listed Seven Short Films that is supposed to appear on the second disc is on the first disc instead--a fact that is likely to confuse you, as it did me, if you decide to go ahead and watch the extra movies before you dig into the Monsoon Wedding supplements. You might find yourself nosing around on DVD 2 looking for a movie that isn't there. Possibly because it had a strong influence on the filming of Monsoon Wedding, The Laughing Club of India is attached to the main feature's bonus material. It's a 2000 documentary, just over 35 minutes in length, that looks at the rather puzzling concept of "laughing clubs." These were a popular occurrence in Bombay, a gathering of folks to get together and...laugh. In its way, it fits in with Nair's other work in that it looks at the lengths people will go to get by and alternative choices that may seem strange to outsiders but that work for the individual. The laughing clubs are an attempt to create something positive in a world that may seem overwhelmingly negative, a celebration of life for the sake of it. A monsoon can come as rain, or it can come as a giggle fit.

Mira Nair

These themes come up again and again in the Seven Short Films collective. The other six of these are featured on DVD 2, and they are a real treat. These are all rare pieces helmed by Mira Nair, spanning three decades, from 1982 all the way up to 2008, three documentaries and four fiction films, some as short as eight minutes, some as long as an hour. Each movie is preceded by an optional video introduction by Nair where she discusses at length her inspiration and some of the details of each production.

The lead documentary, and Nair's first real cinematic endeavor, 1982's So Far From India should be of particular interest to fans of Monsoon Wedding. Nair and photographer Mike Epstein follow an Indian immigrant from his new home in New York back to his old village in India. There he is reunited with his wife and a child he has never really met. Their marriage was arranged just before the man left for the U.S., partially to keep him from getting involved with any Western women. The movie explores the concept behind this arrangement, as well as the economic practicalities of a family relocating across the world. As in many Nair films, her characters are displaced, caught between two cultures, searching for a new personal niche.

India Cabaret (1985) is the second documentary. It's a character study of several Indian strippers, made as a kind of social experiment to examine what makes one woman "bad' and another "good." Frank conversations with the girls are intercut with their performances, and Nair even follows one of their regular clients home and talks to his wife, juxtaposing her feelings about a woman's role in a man's life with the strippers' feelings about having taken their destiny in their own hands. The film can be quite funny, but also quite sad, especially as it follows one of the girls back to her home village and shows how her family now shuns her, despite her being the most successful among them. India Cabaret ends on a positive note, however, letting us see how the most outspoken dancer, Rehka, manages to make her plan for a new life come to fruition.

The four fiction films that follow the documentaries were all made for politically motivated anthologies, and they focus on themes of social change and personal identity. The 1993 piece The Day the Mercedes Became a Hat follows a white family leaving South Africa as the power balance is shifting all around them, while Nair's 2002 segment of 11'09"101 - September 11 shows how another family must fight to maintain their ground in the country they've chosen for themselves. Scripted by Monsoon Wedding-scribe Sabrina Dhawan, the 9/11 story is based on the actual plight of the Hamdani family, whose son Salman disappeared on 9/11. It's a true mystery, since Salman had no connection to the Twin Towers, he should have been on his way to work when they fell. Upon being reported missing, he was initially branded a terrorist despite there being no evidence to suggest that was true. When his body was found at Ground Zero, it was discovered that Salman had died a hero. He had been trained as an EMT and had rushed to the attack site to help people.

Salman Hamdani's mother never gave up on her son, nor does she give up on the country that he died in aid to, despite them getting it so wrong about him. Nair is sympathetic to these kinds of patriots, whether they are on the right side of justice or not. The white family who, like so many others at the time, flees from South Africa in The Day the Mercedes Became a Hat also draws empathy from the filmmaker, who as a resident of South Africa herself, realized that there were whole generations of Caucasian immigrants who knew no other home.

Sexual politics take center stage in the final two films. 2007's Migration was made in India as part of an AIDS awareness project that Nair produced, and 2008's How Can It Be? was part of a film that was meant to express different facets of the global community. The former is a none-too-subtle melodrama that moves up and down class lines as infidelity and deceit opens the way for HIV to spread; the latter is a story of a religious woman, played by Konkona Sen Sharma, who decides to leave her home and family and pursue a different passion. Both offer tough choices with equally tough consequences, though How Can It Be? is about the sacrifice asked of women who want to affect positive personal change and Migration is about how poor choices affect us all. Watch for Wedding's Vijay Raaz in Migration, this time playing the role of on-the-street condom pitchman.

Some of the fictional shorts are a little obtuse, but they are all intriguing. They are also quite lovely, shot with Nair's usual eye for detail and sometimes sporting more experimental framing than in her more conventional narrative pictures. The documentaries also shed some light on Nair's creative origins and how she used nonfiction to develop her incredible powers of observation. These are like the missing links in the cracks of a filmmaker's evolution.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

Sunday, October 18, 2009

DUSAN MAKAVEJEV: FREE RADICAL - ECLIPSE SERIES 18

My first exposure to Serbian director Dušan Makavejev was reviewing his experimental 1971 feature WR: Mysteries of the Organism when Criterion released it on DVD a couple of years ago. As is immediately obvious from reading that piece, I was not altogether won over by Makavejev's style. WR was both too all over the place and too on the nose for me. Though his filmmaking was playful, it was also too heavy in its intentions. To say I wasn't all that excited when this new boxed set came around would be to put it mildly.

Well, I was wrong. I should have been excited. Dušan Makavejev: Free Radical - Eclipse Series 18 strikes me as having everything I felt WR was lacking. The three films here, representing Makavejev's earliest full-length work, are as stylistically inventive as anything out of the French New Wave and rooted enough in traditional storytelling to keep them from showing their age. If what was radical yesterday was content on being merely radical and nothing more, it can appear predictable or mundane today; if it has a solid foundation to give the experiment something firm to stand on, the material can sustain its freshness and speak to audiences regardless of the era. Such is the case here.

Dušan Makavejev: Free Radical showcases work the writer/director made in the former Yugoslavia over a four-year span, from 1965 to 1968. It kicks off with Man is Not a Bird, a romance wrapped up in the politics of everyday struggle. Set in a mining town near the Bulgarian border, it involves the arrival of a revered construction foreman named Jan Rudinski (Janez Vrhovec). Rudinski has been charged with updating the copper mill to be compliant with safer, more efficient modern standards. He meets Rajka (Milena Dravić, the sexy star of WR), an attractive young hairdresser who is used to turning heads in her sleepy 'burg and just as used to putting those heads back where they belong. She sets Rudinski up with a room in her parents' house, and she and the older man eventually have an affair. Perhaps it's the appeal of the new and the different, or maybe it's the attraction of the temporary that brings them together. Maybe it's the fact that they can have an intelligent conversation, or even his indifference. It's hard to say how the fires of passion are stoked, but Rajka also ends up with a local truck driver, the rapscallion Bosko (Boris Dvornik), whom she beds on the night Rudinski is honored for his good work.

Perhaps Rakja is punishing Rudinski for valuing his job over her. That would actually make it ironic that she ends up having sex with Bosko in his truck, his mobile workplace. There are a couple of thematic threads that run through Man is Not a Bird that suggest valuing one's work over one's personal relationships is not a good thing. Running parallel to this story is the tale of Barbulović (Stole Arandelovic), a boozer whose antics keep getting him in trouble. He is stepping out on his wife (Eva Ras), who makes no bones about confronting the other woman and raising a stink about how Barbulović is always moaning about having to work at the factory but then blows his money on harlots. Our introduction to the cad actually comes at the beginning of the film when he is arrested for a nightclub brawl he claims to have had no involvement in. The violence ended with the stabbing of the performing chanteuse, whose cautionary tale about the roving eye of love could have saved all of these folks a lot of trouble had they heeded her warning. The film is bookended with a more grandiose orchestral concert, the one given in Rudinski's honor. There is a subtle commentary here, of the low-culture performance for the workers vs. the high-culture performance for the boss. Both musical interludes indicate some form of betrayal.

These two music numbers are interwoven into the narrative in their complete form, shot as if part of a documentary. Makavejev also shoots the factory scenes with a similar style, showing the effort of the workers in all its dirty detail, sharply contrasted against the more staged cutaways to the factory owner far away in his office. He is portrayed as corrupt and clearly in control of the communist party, dictating their policies like some kind of mobster lobbyist. There is no question where Makavejev's sympathy lies, and he clearly has affection for the working class. He doesn't believe they are perfect, but he does appear to enjoy showing them slacking off and doing whatever else it takes to get back a little of their own from those who would exploit them. Their foibles are shown with humor, whereas the higher-ups are far more sinister.

Not that it's so black-and-white. The director also has a sympathetic interest in Rudinski's predicament. He is a man who is neither one side nor the other, a sort of industrial mercenary who gets the job done when required. Makavejev shoots his encounters with Rakja in an expressionistic manner, capturing their lovemaking in tightly framed abstractions. Even in this early film, Makavejev is exhibiting a penchant for a freeform style, refusing to be locked down to any particular narrative aesthetic. The story takes many detours, seemingly going off track, but then coming back around to sew each added element into the main fabric. The most notable of these sidelines is the hypnotist (Roko Cirkovic) who provides an evening's entertainment by goading his volunteers into doing all manner of crazy things, like thinking they are birds and then watching them flail around on stage, unable to take to the air. Barbulović's wife directly references this stage act by telling her husband's lover how she believes that hypnotism is Barbulović's true talent, that all men lead women into a trance to get what they want. Man is Not a Bird extends this theory to include all social constructs. The need to work, political ideology, romance--these are all a form of social hypnosis, a great con to make us believe we are happy and that we can escape the mundane. Rakja seeks escape from love, for instance, only to have neither lover take her out of this tiny town. This is why man is not akin to birds, because man can't truly fly free.

Sex, crime, science, art, nationalist politics--these all return in some form in Makavejev's 1967 feature, Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator. Once again working with a mish-mash of documentary footage and fictional narrative, Makavejev establishes an alternating formalist structure for the film. It opens with a real-life sexologist, Dr. Aleksandar Kostić, lecturing about man's fundamental needs before introducing us to Izabela (Eva Ras) and her friend (Ruzica Sokić), two switchboard operators out on the prowl for a good time. They meet a Turkish man named Ahmed (Slobodan Aligrudić), a sanitation expert, who takes Izabela home. So begins a long, loving relationship, both tender and sensual, which plays out while trading off with more educational interludes, all of which connect to the main narrative in some way. Izabela playing patriotic music is followed by footage of a real political rally, or a scene of her baking leads to a lecture about the physiology of chicken eggs. (The close-ups of Eva Ras breaking an egg into flour are later echoed in WR.)

We also get a glimpse of Ahmed's job in newsreel-like footage about Yugoslavia's rat problem. He is part of the crew of exterminators who are trying to rid the country of gray rats, which themselves were allowed to enter the land so that they would get rid of the black rats. It's the nasty cycle of power, one political party coming in to oppress another. It's also meant to make us distrust Ahmed, as he is a suspect in Izabela's homicide. As if flipping the switch between fiction and documentary weren't enough, Makavejev has also worked a little murder mystery into the script. Structured like a true police drama where we know there has been a killing before we know how or why, the second interlude shows Izabela's body being retrieved from a well while we hear a criminologist, Dr. Zivojin Aleksić, explain the process of cleaning and identifying a corpse. It's a harsh, clinical lecture, and it makes us feel uneasy even though our connection to Izabela is not all that strong as of yet.

Love Affair connects back to Man is Not a Bird in that some of the tragedy is born out of infidelity. Izabela is constantly being hit on by the postman (Miodrag Andric) who delivers to her work, and she eventually relents. In a scene reminiscent of Godard, Izabela breaks the fourth wall to address the audience directly, to confess that she is weak and, as she puts it, not made of wood. It's a reasonable appeal. Makavejev seems to be saying that our social structures, our fear of sex and our subsuming our individual desires to the greater need of the State leads to unnatural reactions. Unhappy people act in unhappy ways, and once we finally see the death occur, we realize that Ahmed is not simply some cold-blooded killer. This is not a grandiose revelation, Makavejev doesn't underscore it with an ironic orchestral swell the way he does the sexual ruining of Rajka in Man is Not a Bird, but rather shows it in a very plain fashion. It's sad enough as it is. The scene perfectly illustrates the ease with which the filmmaker moves between styles. The cuts between the fact and fiction are seamless; in fact, in Love Affair, he really blurs the lines between the two. The naturalistic staging of the drama makes it almost indistinguishable from the documentary footage. It's like meta-Neorealism.

1968's Innocence Unprotected gives Dušan Makavejev a remarkable opportunity to obliterate the lines between fictional filmmaking and documentary storytelling. In this movie, Makavejev repurposes an old film that had long gone out of circulation despite being Yugoslavia's first sound picture. It was made during WWII by Dragoljub Aleksić, an acrobat and strongman. Though it was shot entirely on the sly, it was later misconstrued as a film made in collaboration with the Nazi occupiers and not just banned from being shown, but also removed from the history books.

Makavejev takes this bizarre melodrama and recontextualizes it. Having tracked down the living actors and crew members, including Aleksić, Makavejev creates a non-fiction frame around the old footage, moving back and forth between the original production and people's memories of the same. The tale is pretty fantastic, including performers hiding in a soundstage darkroom while the German propagandists shot their own footage outside. Aleksić made Innocence Unprotected in the hopes of making money, and in its original form, it's mostly a self-aggrandizing excuse to show off his freakish stunts. Breaking and bending iron with his teeth, making his muscles dance, dangling from an airplane by holding a leather bit in his mouth--Aleksić is the kind of sideshow performer that Makavejev loves (see also the circus scenes in Man is Not a Bird). He's a true original, an individual who lives his life as he wishes, and one that also ran afoul of a bureaucracy that refused to let such characters roam free.

In Makavejev's hands, Innocence Unprotected becomes both propaganda for the common man's power to resist oppressive governance, but also a parody of the propaganda. I actually started watching the movie believing it to be a pitch-perfect mockumentary, right down to the bad acting in the "found" film; only midway through did I stop and read the liner notes and realize this was entirely real. An incisive social critic, Makavejev has found a greater meaning in a particular piece of art by examining its historical context. He uses newsreel footage of German atrocities and maps illustrating the warmongers' advances on his country's border to embolden Aleksić's ridiculous fictional romance with greater meaning. A wicked stepmother (Vera Jovanovic-Segvić) selling out her orphaned stepdaughter (Ana Milosavljević) to a wealthy scoundrel (Bratoljub Gligorijević), only to have her rescued by the unflappable hero makes for a wonderfully blunt allegory (complete with twist ending: Aleksić pretty much ran off with whatever money was made before the film was banned, leaving his comrades out in the cold). It illuminates the struggles of the Serbian people, first under the Nazis and then under the Socialists, as well as the personal struggles Dušan Makavejev must have gone through in order to make movies under the censoring eye of the government. Not unlike Aleksić, Makavejev would eventually be persecuted for his art. After his next film, he would be exiled from his homeland for nearly two decades.

Seen as a whole, the three films collected in Dušan Makavejev: Free Radical - Eclipse Series 18 show the emergence of a new cinematic voice, a singular artist who would go on to further challenge his audience and often alienating people--including this particular stuffy critic. This trio is playful, creative, culturally rich, and full of insightful commentary on the human condition, particularly the way our personal lives become entangled with society's imposed restrictions. Dušan Makavejev proves himself to be every bit as inventive as his European contemporaries, and as full of cinematic whimsy and film knowledge as anyone who wrote for Cahiers du Cinema. This boxed set is a true treasure.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

DELAYED DEVOTION

My apologies to my readers for missing an update last week. I hate not hitting my deadlines, even self-imposed ones. I got caught up in a variety of things, including computer troubles, several other freelance commitments, and I think the general sludge of autumn emerging. Everything these past couple of weeks has taken longer than expected. This is only the second or third time in two years that I have missed my weekly post on this blog, so I suppose I have an okay track record. Like always, I'll make up for it by upping the output here in the next two weeks, staring with Dušan Makavejev: Free Radical later today, and then working my way through the next three Criterion releases: Monsoon Wedding, Z, and Wings of Desire.

Never fear, I may have stumbled, but I don't stay down for long. Thanks for your patience, and while you wait, please enjoy this hold music...

Never fear, I may have stumbled, but I don't stay down for long. Thanks for your patience, and while you wait, please enjoy this hold music...

Saturday, October 3, 2009

THE FRIENDS OF EDDIE COYLE - #475

Things aren't so good for Eddie Coyle right now. Old age is not the best place for a hood to find himself, and now that he's cresting 50, Eddie can't face the consequences of his life. A smuggling job gone wrong has a prison sentence hanging over his head, and if Eddie gets locked up, he knows that will be the end for him and his family. His kids barely know him as it is. Eddie knows the score in all things, and he fears that it will end up as a running tally of misfortune rather than a jackpot. Other crooks retire to Florida, he just wants his stake on the beach, not this spot in limbo. Eddie is working small-time jobs on the side, mainly procuring guns for bigger heists. His brain is sharp, but his body is limited. His pals have given him the cruel nickname of "Fingers." It's because one time Eddie screwed up and landed the wrong person in jail, and so the organization exacted their own punishment for the mistake: Eddie's hand was stuck in a drawer and it was slammed shut on him, making it so his digits will never be right again.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle is a 1973 crime movie directed by Peter Yates (Bullitt

Eddie's friends are the usual collection of bad guys and black marketeers, and their classification as allies is questionable at best. Among them is Artie Van (Joe Santos) and Scalise (Alex Rocco), the go-between and the bank robber whom Eddie is buying guns for. Yates shows us several of Scalise's bank jobs, though largely keeping us in the dark as to his identity and the inner workings of his gang until midway in the picture when we finally see him and Eddie together. Just like everything else in The Friends of Eddie Coyle, the robberies are filmed in a stark, meticulous manner, placing faith in the audience's ability to submerge themselves fully into this underworld and go along with a minimum of explanation. Scalise's crew begin each heist by going to the home of one of the bank executives, and they take the man's family hostage until the robbery is done. All of them wear identical masks so no single thief distinguishes himself. They are careful and exacting, no screw-ups. Nobody moves, nobody gets hurt.

Eddie trusts Scalise, and he wants to be in good with him because if he can keep out of jail, Scalise is likely where his big retirement score would come from. To get the pistols Scalise requires, Eddie deals with Jackie Brown (Steven Keats), an arms dealer who represents a totally different era than the one Eddie has come out of. Driving a lime green hot rod, wearing his hair long, getting excited over his illegal booty, Jackie comes off as someone who is just playing around. Eddie takes a kind of fatherly role with him, schooling him on the consequences of his actions. There are extended scenes of Mitchum explaining to this kid just what could happen to him if he wises up. It seems to work, as Jackie develops a healthy paranoia when working with the people who want to buy and sell the rifles.

Another of Eddie's friends is Dillon (Peter Boyle), the bar owner who hired Eddie for the job that got him busted. Eddie is a stand-up guy and isn't selling Dillon out, but a weary tension still exists between them. Eddie can say he will forgive and forget, but until his jacket is clear, not really. Dillon's bar is a bit of a criminal hub, and this makes Dillon a pretty important informant for the police. He has regular contact with Dave Foley (Richard Jordan), a cop who feeds him $20 bills in exchange for info. Their encounters are strange. They stroll the city engaging more in philosophical abstracts than they do with illegal specifics. If Eddie is in limbo, these guys own the keys to the kingdom. The way the one-eyed man is the king of the blind, these guys are the timekeepers in the waiting room of eternity. They are content to wait this out.

Paul Monash, a veteran of television and of other crime-oriented pictures, is himself content to leave out the unnecessary, and he revels in the jargon and the speech patterns of his bad guys (as well as a little Bostonian lilt thrown in, reflecting the city where the movie is set). Unlike a lot of modern writers, who are afraid that if they don't footnote every piece of slang the audience will get scared and leave, Monash has faith in the words to carry their own meaning. Context and performance can create the space for an unfamiliar turn of phrase to make sense. If the audience believes what they are watching, they aren't going to get hung up on the particulars. This trust goes both ways, too. For having faith in the viewer's intelligence, the viewer gives that faith back and trusts Yates and Monash when the filmmakers purposely leave things vague. How all the pieces are going to fit together is never readily apparent in The Friends of Eddie Coyle. I suppose on paper this movie could be charted as a fairly standard outline, but if the filmmakers ever made one, it's like they removed every third item, creating blanks they would only fill in by suggestion later.

Eventually Eddie sees a way out. The cop Foley could vouch for him with the prosecutor if Eddie turns snitch. It's the one value left in Eddie's criminal code that he's hung on to. In fact, he's still not ready to give up the other guys in the smuggling operation, but maybe he'd sell out Jackie. The problem is, working with the police isn't that different than working with the crooks: once you're in, you're never getting out. They always want more.

I had heard a lot of praise for The Friends of Eddie Coyle, and I had been interested in seeing it ever since I read an essay about the flick in the back of Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips' comic book series Criminal

This makes the brutally ironic ending all the more harrowing. I've written about that killer noir ending in many of my other reviews of crime movies, the sort of final moment where the plan falls apart, it's all for naught, crime doesn't pay. Usually, that means losing the money, walking away empty handed. For Eddie Coyle, it's the whole shebang. Stitched up and framed, stuck on the wrong end of poetic justice, he pays the big price. It's an existential conundrum, the consequences we can't outrun, the very fate we tried to steer away looping around to bite us on the ass. And yet, the game is still being played. Those kings of limbo? The cop and the informant? They are nothing less than God and the devil, playing at both sides and meeting in the middle, bemused by the cruelty of human life.

Included with the Criterion DVD of The Friends of Eddie Coyle is a reprint of a 1973 Rolling Stone article writer Grover Lewis put together after a visit to the movie's set. It's fascinating how Robert Mitchum talks to Lewis. He pontificates on a variety of subjects, largely unprompted, and he sounds a lot like Eddie schooling Jackie. He is full of old wisdom and he can't understand how said wisdom is not more common. Is his performance in Eddie Coyle an actor so dominating a role that it becomes him, or did Mitchum choose to be in the film because it matched who he was? It's impossible to say, but reading how he knew Eugene O'Neill and Dylan Thomas, or about his visit to Vietnam, or why he acts simply because he doesn't want to do harder work, it really seems like we're getting to know an actor who we think would otherwise be closed off and protective of his true identity. I expected someone more like Cary Grant, who was careful of his brand and left himself back at home. Not so with Robert Mitchum, he is what he is, and what he is ended up on the screen.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)