Thursday, March 31, 2011

SIDELINE: MORE REVIEWS FOR 3/11

IN THEATRES...

* The Adjustment Bureau, in which Matt Damon and Emily Blunt get entangled in a mind-warped romance. My original headline was "Like The Notebook for boys...or maybe Inception for girls?" but, you know, girls like Inception.

* Jane Eyre, yeah, yeah, Jane and Rochester really love each other. I get it. Wake me when it's over...

* Monogamy, an intriguing movie about love, relationships, obsession, growing up. You know, same old thing. Starring Chris Messina and Rashida Jones.

* The Other Woman, in which Natalie Portman gets really, really sad. Really.

* Paul, the new Simon Pegg/Nick Frost comedy takes on sci-fi as the genre of choice, and though it's funny, you will miss Edgar Wright.

* Source Code, Jake Gyllenhaal goes back in time eight minutes to stop a bomb plot--over and over until he gets it right--in the new film from Moon's Duncan Jones.

ON DVD/BD...

* Around a Small Mountain, a self-important dud from Jacques Rivette, starring Jane Birkin and some Italian guy.

* I Clowns, Federico Fellini's playful early '70s documentary about...well, clowns!

* A Film Unfinished, a haunting documentary piecing together a lost Nazi propaganda film shot in the Polish ghetto.

* Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould, a wonderful documentary introduction to the fascinating pianist.

* Heartbreaker, a rom-com that reminds us that the French make crappy movies, too.

* How Do You Know, the romantic comedy in which the mighty James L. Brooks falls on his face and tries to throw Paul Rudd and Reese Witherspoon down first just to soften the landing. And to think they trusted you, James!

* Jackass 3: Unrated, this time, the winner takes all the smuggled plums.

* Our Hospitality: Ultimate Edition, a spiffy new release of the old Buster Keaton classic.

* Mad Men: Season Four: Like you need me to tell you it's any good.

* Sunday in New York, a flaccid 1960s romantic comedy with a very non-flaccid, sexy Jane Fonda.

* Teen A Go Go, a DIY documentary on 1960s Texas garage bands.

* Two in the Wave, a documentary about Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard that mostly preaches to the choir, but is still entertaining.

* William S. Burroughs: A Man Within, another excellent documentary, this time about the oddball author of Naked Lunch.

Labels:

documentary,

fellini,

godard,

James L. Brooks,

other reviews,

silent cinema,

truffaut

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

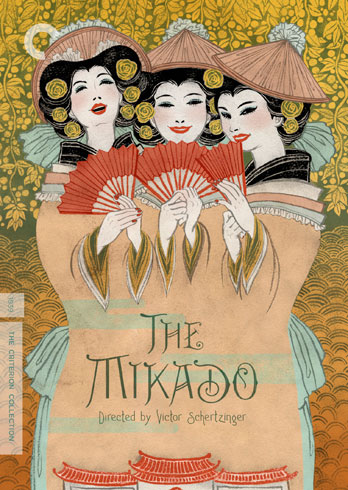

THE MIKADO (Blu-Ray) - #559

It surprises me that more Gilbert and Sullivan musicals haven't been adapted to film, but as Geoffrey O'Brien's liner notes to the new Criterion Blu-Ray of The Mikado inform us, this 1939 adaptation was the duo's first time on the silver screen, and there hasn't really been much more since. Mike Leigh's Topsy-Turvy, which is being released in conjunction with this under a separate cover [review], is the only comparable, substantial portrayal of Gilbert and Sullivan in cinema. Fittingly, Leigh's movie detailed the creation of the first-ever stage production of The Mikado and showed the backstage shenanigans at the Savoy, where the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company performed. Thus, the extended pedigree is intact: this late-'40s feature was an official production of the Opera Company, then run by Rupert D'Oyly Carte, son to Richard, the man who had commissioned The Mikado, who was one of the characters portrayed in Topsy-Turvy. This movie is part of the family business and a stepping stone between the truth and its fictional recreation. Sorting out the lineage is a plot bendy enough for Gilbert and Sullivan themselves!

This three-strip Technicolor production was directed by Victor Schertzinger, a composer who had also made a name for himself in the motion picture business (his next film was Road to Singapore

Given the strange, farcical plot of The Mikado, I think this may have been a good decision. Had the same story been undertaken using more standard film language, it would have seemed even more odd than it already does. As a Gilbert and Sullivan neophyte, I was amazed by the dark and twisted substance of the operetta's narrative. In a nutshell, the son of the Japanese Emperor is told he is going to marry an older woman of his father's court, the mustachioed Katisha (Constance Willis). Rather than submit, the boy (played by Kenny Baker) runs away. He hides out in a town called Titipu, where flirting is punishable by death. He poses as a minstrel and goes by the name Nanki-Poo and falls for the pretty Yum-Yum (Jean Colin) upon first seeing her.

Too bad for Nanki-Poo, but Yum-Yum is engaged to Ko-Ko (Martyn Green, a D'Oyly Carte alum), who himself has been condemned to execution for flirting with his fiancée. I don't know why Nanki-Poo gets away with his flirting, because even Ko-Ko is aware of it, but he does. The tale is a tangled mess, and I suppose the convolutions of this plot are best left where they are. Ko-Ko is given a reprieve under some weird statute that makes a man his own judge and executioner, and since he can't decapitate himself, he can stick around and marry Yum-Yum. Except then the Emperor, a.k.a. the Mikado (John Barclay), gets upset that the no one's head has been cut off for a while, so he tells Ko-Ko to get chopping or lose his job. Since Ko-Ko is the only man on death row in Titipu, he's back at square one, until he discovers Nanki-Poo is so distraught over Yum-Yum that he wants to kill himself. Ko-Ko makes him a deal that if he consents to be his stand-in on the block...well, things continue to grow more gnarled from there. Life and death and love and everything after hang in the balance.

This kind of up-and-down storytelling, full of reversals and re-reversals and flips and flops, was what was referred to as the "topsy-turvy" style and, amusingly, was just what W.S. Gilbert was trying to get away from when he started out on his Japanese story. I can see why audiences liked it, however, it definitely keeps the action moving between songs, of which there are many, including famous numbers like "Three Little Maids from School." Most of the songs are jaunty and full of wordplay, a few are a little heavier, punctuating moments of romantic gravitas. Given how the story here never stops twisting, I'm a little surprised that The Mikado doesn't move faster. I can only imagine it with some kind of screwball Howard Hawks pacing; I guarantee no one watching would ever get bored if it had been run through at the same speed as His Girl Friday

Still, this presentation of The Mikado is one of those interesting historical excavations that has earned Criterion so many fans. Where else would I ever see the 1939 production of The Mikado, of all things, and where would I ever see it quite like this? The Blu-Ray package offers yet another remarkable restoration. The color image is astounding, full of beautiful texture and lovely variations of tone. There are multiple matte painting backdrops that have a soft, pastel-like hue that look just amazing in high-definition. Likewise, the mono soundtrack has been scrubbed to perfection. The music sounds perfect.

In addition to the silent film promoting the earlier D'Oyle Carte staging of The Mikado, the bonus section features scholarly interviews and a deleted scene, Ko-Ko's song "I've Got a Little List." It's theorized that it was either cut for the political jabs the number takes at recent newsworthy figures (it was updated to include Hitler, a lookalike of whom appears on screen in full Japanese costume) or a racial slur that is usually dropped in modern productions. It's interesting to note that Schertzinger takes advantage of recorded sound to make an audio joke during "List," which I assume was an invention for the cinema.

Tying this release of The Mikado to Topsy-Turvy is a new interview with Mike Leigh. Also, Criterion had New York-based artist Yuko Shimizu, perhaps best known for illustrating the covers to the literary-based comic book series The Unwritten, draw both covers. Shimizu's art definitely has a style fitting the material, and you should definitely take some time scanning the portfolio at yukoart.com. I am also including some of my favorite pieces below.

This disc was provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.

Labels:

blu-ray,

gilbert and sullivan,

hawks,

mike leigh,

music,

Victor Schertzinger

Wednesday, March 16, 2011

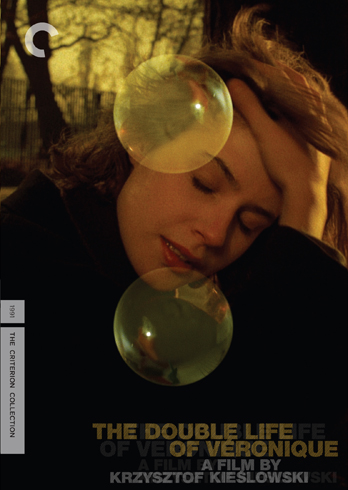

BLU REDO: THE DOUBLE LIFE OF VERONIQUE - #530

For this viewing of The Double Life of Véronique I did something I generally don't do: I read my old review. It's been over four years since the DVD of The Double Life of Véronique was first released, and so that long since I last saw it. I was curious what the me of 2006 had to say about the picture. Was I insightful? Was I way off base? Would how I thought then be a way of thinking I'd even recognize now?

These questions of intellectual identity aren't just the curiosity of a writer who sees how he writes about cinema as an ongoing process, but they are also thematically in tandem with the philosophical and metaphysical questions Krzysztof Kieślowski poses in his 1991 masterpiece. Is it possible that we are more than one person? Forget the idea of a physical double for a second. Maybe the way our thought processes evolve creates separate, parallel versions of ourselves. When we change our minds, some version of who we are splinters off and becomes its own entity.

There is certainly that kind of magical thinking within Kieślowski's screenplay. One could interpret a variety of different reasons for why there is a Polish Weronika and a French Véronique (both played with a fragile intensity by Irène Jacob). Both versions wake up startled from dreams at different times, so maybe one is dreaming the other. Both fixate on an image of one version of themselves during sex, possibly creating a dissociative fantasy. Maybe they are a manifestation of the puppeteer (Philippe Volter) and the fictions he creates. His seduction of Véronique follows the outline of one of his books, and he does create two marionettes in the women's image. Or maybe the external force is the filmmaker, as it is his fiction after all, and there is no more explanation needed here than there is for the sudden change of actresses in Luis Buñuel's That Obscure Object of Desire. It is what it is, the question answers itself. For some reason, I was also reminded of Abbas Kiarostami's Certified Copy [review], particularly in the way Alexandre, the puppeteer, chased Véronique through the street; maybe we could interpret, as one could with Kiarostami's couple, that the game they are playing stops being play and becomes real.

Because up until that point, Alexandre is playing a game with Véronique. He remodels courtship as a kind of scavenger hunt, but one where the disparate pieces of the puzzle are sent to her instead of Véronique having to seek them. It's a love letter delivered as code, and like the riddle of the Sphinx, if you crack it, something remarkable awaits. When she surrenders, all kinds of things begin to happen. Exactly what...ah, well, that's still part of the mystery.

It's amazing how much one can forget about a movie in the years between viewings, and it's also amazing how much more you can notice once you have a basic idea of what you are in for. On one hand, there was so much in The Double Life of Véronique that felt new to me, I almost questioned whether I had seen it at all. Specific scenes and turns of the plot had been lost to my fading brain power. For instance, had I ever seen the Polish woman who had come to Paris, who spies Véronique and recognizes Weronika in her, thus connecting the doppelgangers? I'm not sure.

At the same time, it's interesting to note how much takes on deeper significance precisely because of what you do remember. It's like watching a murder mystery when you know who the killer is. All of that person's actions take on added meaning. Right from the start of The Double Life of Véronique, I was acutely aware of different visual cues, of small gestures or indicators, and of the surreal aura Kieślowski cloaks everything in. The storytelling here is almost episodic, even disjointed, yet one must assume everything is placed where it is for a specific purpose. For instance, the statue of a communist leader that Weronika sees being hauled away at the start of the movie could have a variety of meanings. On one hand, there is the political interpretation. In the early 1990s, European communism was failing. Symbolically, the man immortalized in stone is now the one being tied down and hauled off. He is taken away, and in his place is freedom.

Yet, if we know that later there will also be life in miniature, that the puppets will also be carved imitators of life that require their own string, then the statue is foreshadowing. Going from one to the other is going from large to small, from a universal symbol to an individual one. Our heroine complains of a feeling of not being alone in the world, and that feeling could just as easy be her connection to her fellow man. None of us are alone, we're all in this together.

It's an unknowable feeling, immutable. Like the light that lingers in Véronique's apartment even though the reflective surface is withdrawn, or the reoccurring chord that binds the women together though its origins are unknown. Or maybe it's not so unknowable, maybe it's simple. Like the removal of the dictator gives the Polish people freedom, so too does Weronika's fate make way for Véronique's blossoming. Alexandre's puppet show portrays a ballerina who breaks her leg, and yet despite the crippling injury, she wants to keep dancing. Her will is so strong, she transforms into a butterfly and flies away. Weronika is the ballerina, and Véronique the colorful insect who takes flight.

Before I wrap up, special mention should be made of the fact that this viewing was also my first time watching The Double Life of Véronique on Blu-Ray. Kieślowski's movie looks astounding in high-definition. The Double Life of Véronique is a film that is intricately designed, with specially tuned color palettes and a meticulous attention to every corner of the image frame. The light in this new digital version is warm and full of undulations, and the tiniest detail is given equal due. Take a look at the scene where Irène Jacob is bouncing the rubber ball and she dislodges dust from the ceiling. Minute particles rain down on her, and on Blu-Ray, each one is its own individual sparkle, a glittery cloud of fairy dust.

In terms of supplements, the new edition is an exact copy of the DVD release. The only thing that has changed is the packaging...which kind of sucks by comparison. I can appreciate the compact nature of the small Blu-Ray case, but I prefer the handsome box and book version, which was more like its own art object, a physical treasure chest to unfold, than it was merely functional. For that alone, I'll likely be hanging on to both versions of The Double Life of Véronique even though I'm only likely to actually watch the Blu.

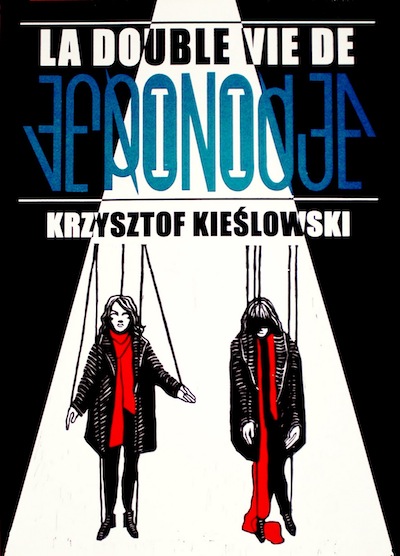

This cool poster by artist Joanna Lisowiec is something I stumbled across doing a search for, well, Double Life of Veronique posters. She made it for a contest. I hope it wins!

This disc was provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.

Tuesday, March 15, 2011

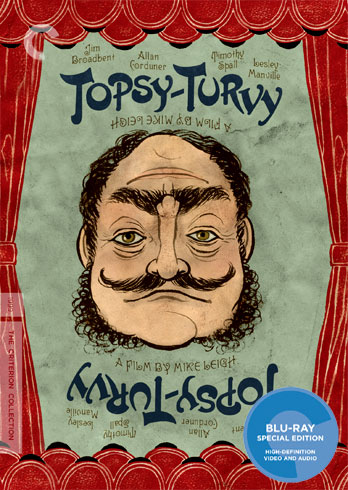

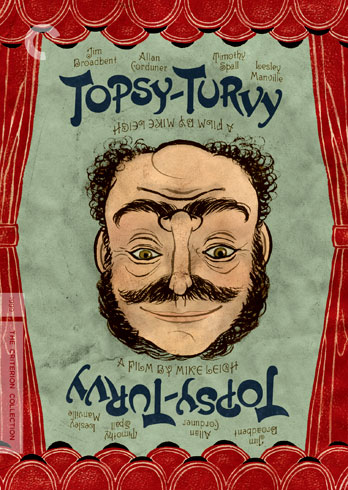

TOPSY-TURVY (Blu-Ray) - #558

In 1885, the writing team of Gilbert and Sullivan were at the peak of success. Even their admittedly mediocre show, Princess Ida, which had just premiered at the Savoy Theatre in London, was predicted to be a smash, despite chafing reviews that called the pair on the proverbial carpet for the repetition in both Gilbert's comical lyrics and Sullivan's orchestral melodies. As a pair, they could seemingly do no wrong.

Mike Leigh's 1999 film Topsy-Turvy peeks in on the famous theatrical legends just as Ida is taking its creative toll on the duo. Arthur Sullivan, played by Allan Corduner, is overworked and unsatisfied, and for the sake of his health, he leaves for the South of France. Upon returning, he rejects his partner's new libretto, instead swearing to write his own grand opera where his music will not be outdone by the singing. Taken aback, W.S. Gilbert, portrayed with panache by Jim Broadbent, can't help but take it personally. He has been laboring on a musical in which a magical potion transforms the citizens of a European mountain town into whatever they wish to be. Sullivan's rejection of this fanciful notion seems little more than a rejection of him personally.

The comedic switch-up in this lost idea was an old stand-by for Gilbert and Sullivan, and it is a perfect example of their "topsy-turvy" style. In their musicals, everything gets turned upside down. Expectations are raised, and then flipped, to the point that the flipping had become what was expected. This is what Sullivan wants taken out of their future work. He wants to portray human drama rather than stick to formula. This doesn't just worry his writing partner, but also the owners of the Savoy (Ron Cook and Wendy Nottingham), who have the team under contract. Art and commerce, the eternal struggle! Could Sullivan turning his own artistic endeavors topsy-turvy spell the end of everything?

As it turns out, no, it doesn't, and the result is the major thrust of Leigh's movie. Topsy-Turvy is the story of the creation of The Mikado [an early film version of the play is also coming from Criterion this month, read my review here]. When Sullivan's wife, Kitty (Leslie Manville, so good in Leigh's most recent film Another Year [review]), drags him to a Japanese exhibition, the lyricist is inspired by the things he sees. He starts writing a new comic opera about a Japanese executioner, and suddenly a whole new ball is rolling. Leigh's film, which he both wrote and directed, chronicles all the backstage planning, all the bruised egos and the hard work and the dangerous peccadilloes, that keep a theatre company running. Topsy-Turvy is an elegantly crafted ensemble piece, with enough side plots to give each important performer their due and allow the actors to establish believable and complete characters, but never so much that any one can derail the main story. It's an often-brittle tale, examining the insecurities of performing life. The very need for acceptance and validation is pretty much its own guarantee that there will never be enough of either, not even when you're on top of the world. That, in its own way, is topsy-turvy, as well.

Mike Leigh and his production team meticulously re-create the Savoy and its lavish stage productions. In addition to songs from The Mikado, which are sprinkled throughout the narrative at key moments, we also get glimpses of Princess Ida and The Sorcerer, both to show the Gilbert and Sullivan style and also, in the case of the latter, to show the magic they created, both as acts of fiction and in the act of creating that fiction. Though Leigh is often known for his far more serious human comedies, the kind of thing that Sullivan could have probably appreciated and Gilbert might have dubbed boring, Topsy-Turvy is more expansive and fancy than his modern kitchen-sink style. Dick Pope's photography has a sophisticated sweep that frees it from the theatre's proscenium arch and transforms stage craft into cinema craft. We are never stuck on the boards, we are with the audience and the crew and the performers all at the same time.

I guess in a way we could also call the film's extravagant style "topsy-turvy" in that it does turn our expectations of a Mike Leigh movie on their heads--and with rather successful results. The attention to detail that Leigh takes is essential to his story. In his own subtle switch-up, once The Mikado is underway, the roles reverse, and while Sullivan contentedly trucks along with the new material, Gilbert gets serious about creating something authentic. While the music and even the lyrics are very British, Gilbert wants everything else to be true to the source. He rejects choreographed kitsch and tries to mimic what he sees in kabuki theatre and real Japanese life (albeit the lives of the immigrants visiting his country). Costumes are all based on traditional sketches, and even slimming undergarments are banned because it would change the natural shape of a kimono. As Broadbent plays him, Gilbert goes from the typical humorous blowhard to an artist of great intensity. My favorite moments are when the writer comes off the cuff with a clever joke and chuckles to himself about it: the self-satisfaction of one's own humor.

The whole approach of Topsy-Turvy is subtle and generally light as air. The intricacies of the story structure aren't immediately obvious. Leigh's anecdotal technique keeps an even pace, letting each backstage story play out, hitting the punchlines (which are uniformly funny), and then moving on. This makes it a little surprising when the film springs a heavy denouement on the audience. Despite all the laughs that Leigh has gathered along the way, he has also slowly exposed the darker sacrifice of artistic obsession. In their pursuit of acclaim and adulation, the troupe not only demands a lot of themselves, but also the people around them. Both Gilbert and Sullivan have chosen the ephemeral muse over the permanence of family, and what that means for the women in their lives comes out in different, yet equally heartbreaking ways. Manville gets a powerful scene where she describes her own surreal version of a Gilbert and Sullivan production, while Shirley Henderson, playing an actress who longs for Gilbert's approval, gets one last monologue and the movie's final song. She sings "The Sun Whose Rays Are All Ablaze," a solo ballad from The Mikado that, though quiet and plaintive, rings out as an insistent declaration of her determination to tell her own story.

Tomorrow, she will sing the song again. And there will be another production to follow. Even Kitty asks Gilbert what comes next, though The Mikado has only just premiered. The quest for originality demands its own repetition. Topsy one day, turvy the next.

The new Criterion Blu-Ray of Topsy-Turvy packs an incredible level of detail into its 1.78:1 transfer. Dick Pope stages many intricate shots of the theatrical production within the film, shooting from the theatre balcony, or sometimes right in the thick of the chorus, and in either case the image goes deep and the individual flourishes all get their proper clarity. Colors are rich and vibrant, with excellent skin tones that become all the more apparent as the stage actors wash away their make-up and we see the difference between artifice and naturalism up close. There are no hints of digital noise reduction, nor are there any other tell-tale signs of technological manipulation. The image is clean and vibrant throughout.

Criterion has packed a bunch of extras onto this new release, starting with their usual booklet, which features photos, credits, and an essay by Amy Taubin. There is also an explanation of the artistic technique that Yuko Shimizu used in creating the cover; interesting to note that, judging by the Criterion website, the Blu-Ray cover is printed with the image oriented one way and the standard DVD has it printed the other way. Chapter listings are printed on the inside front cover of the case.

Other extras include an audio commentary, deleted scenes, and a conversation between Leigh and his musical director. The Blu-Ray has them on one disc, the standard DVD on two.

Perhaps most pleasing of all of these is a the short film, A Sense of History (1992; 26 minutes; presented in HD), written by and starring Jim Broadbent, directed by Mike Leigh. Broadbent stars as the Earl of Leete. Mostly a one-man show, it features the Earl leading a camera crew around his family's opulent estate, which has been in the clan for over 900 years. As he conducts the tour, talk turns wistful and nostalgic, and soon the family history turns dark and the personal history gets darker. It's all told with the same matter-of-fact, upper-crust sense of self. There is no real reflection, no remorse: just the facts of privilege. It's an excellent piece of work, smartly and subtly packing a lot into a very short time span.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Thursday, March 3, 2011

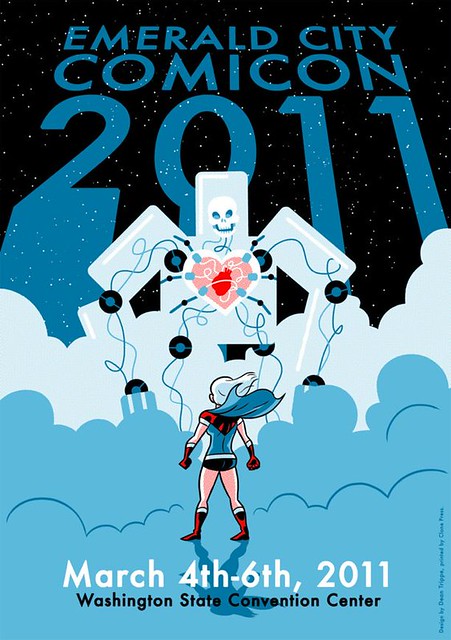

READER MEET AUTHOR: EMERALD CITY COMIC CON (Seattle, WA)

I am heading off today for Seattle for three days of hawking my wares and indulging in pop culture. Come to Emerald City Comic Con this weekend and visit myself and Joëlle Jones at Artist Alley table M-29. We will have all of our books, and Joëlle is bringing her daily doodles and other art for sale. Stuff like this. You can even get a commission from her if you like, or have us sign copies of our publications that you already own. We're agreeable people!

Wednesday, March 2, 2011

YI YI (Blu-Ray) - #339

Fatty: “Life is a mixture of sad and happy things. Movies are so lifelike, that’s why we love them.”

Ting-Ting: “Then who needs movies? Just stay home and live life!”

The Taiwanese film Yi Yi is, in fact, about life, but it also reminds of us why we actually like movies, too. Edward Yang’s 2000 feature has an epic length, but a most human scope. Clocking in at nearly three hours, this family drama takes its time looking around in the lives of the Jian clan. It begins with a wedding and it ends with a funeral, and Yi Yi covers all the ups and downs in between--though really, rather than being pointed peaks and valleys, the graph of this narrative would be more like a wavy line. True life isn’t that sharply defined.

A lot happens in Yang’s opening sequence. The basic relationships are laid out and the various emotional conflicts indicated. A-Di (Xisheng Chen) is marrying Xiao Yan (Shushen Xiao), who is in an advanced state of pregnancy. Apparently, A-Di jilted his long-term sweetheart Yun-Yun (Xinyi Zeng) to have his affair with Xiao Yan, and his mother (Ruyun Tang) has not forgiven him and goes home before the reception. She lives with her daughter Min-Min (Elaine Jin) and her husband NJ (Nianzhen Wu), and the old woman has a stroke while everyone is partying, an event that her granddaughter, Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee), blames herself for. Grandma collapsed taking out the trash, which was Ting-Ting’s job. She fears her bad behavior is why the old woman is in a coma, and if she can be good long enough to earn her forgiveness, Grandma will wake up.

Meanwhile, the Jian men are having women trouble, it’s not just A-Di. NJ runs into his high school sweetheart, Sherry (Suyun Ke), in the lobby of the hotel where the reception is being held. She is visiting from America, where she moved after NJ broke her heart without explanation. Maybe the father’s sins have been passed on to the son, then, and it’s karmic retribution that is causing little Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang) to always get picked on by girls. Yang-Yang is an interesting character, as he mostly stands apart from the rest. His dramas with other kids and the dean at his school are his own thing, and his exploration of new experiences is different than the rest of his family, who are mostly dealing with what they already know. The grandmother’s poor health, for instance, puts her daughter on a spiritual quest and makes Yang-Yang’s sister question her moral health, but Yang-Yang is asking philosophical and scientific questions. He is trying to figure out how it is we look at the world the way we do.

Which, when you think about it, isn’t all that different than what all the others are trying to figure out. How did I get to be this way, and why doesn’t it make me happy? Long after she ponders the pointlessness of cinema, Ting-Ting asks, “Why is the world so different from what we thought it was?” In Edward Yang’s fictional reality, it’s not really an either/or proposition, everything is of one piece. It’s why he named the movie Yi Yi, which literally translates as “One One,” but it’s also meant to be like a band leader counting off before a song. “A One and a Two...” is kind of the official translation, or more like a subtitle. As Yang explains in his press notes, life is about ones and twos. It’s all the same, and all separate, both apart and joined all at the same time. Each new moment can also be a potential new start.

Thus, a spiritual journey can easily run alongside a more logical examination and mother and son can end up in the same place. Or, in one of Yi Yi’s most touching sequences, Ting-Ting goes on her first date ever at the same time her father goes on what is the first date of his second chance. Both nights out are remarkably similar, and they end with heartbreak and confusion. Yet, for all of these coincidences and shared experiences, life itself is seemingly random. Why else, then, would the screw-up brother A-Di stumble into good fortune despite squandering so much, and Ting-Ting have such trouble despite her attempts to be good? Amidst all these criss-crossed romances and bruised feelings, there are no real checks and balances. Things go one way or they go the other. A one or a two.

There are many modern movies one could compare Yi Yi to. In some ways, the dissatisfaction and the potential dangers of the different personal quests remind one of Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm [review]; in how the family works as a unit partially because of how badly the pieces sometimes fit together brings to mind Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Still Walking [review]. Edward Yang approaches his material with more patience and editorial distance than either of those. His work is less stylized than Lee’s and more open than Kore-eda’s. He uses multiple points of view to get at the truth--peering around corners, looking across corridors, and examining reflections to search out what might otherwise not be seen. Young Yang-Yang has a theory that we can only know half of what is real because we can only see what is in front of us. So, he goes around photographing the backs of other people’s heads so they can see themselves as only others can (the DVD cover makes even more sense once you see the film). In this way, the writer/director also seeks out the answers his characters may never find.

Which isn’t to say that Yi Yi is without mystery either. There are some things that Yang isn’t going to put too fine a point on--Sherry’s lonely decision and the origin of the paper butterfly, to name two. Like I said, life is not that sharply defined. The important thing is that the filmmaker doesn’t forget the individuals who stand in this sea of questions, and in so doing, doesn’t allow them to forget themselves.

There is a beautiful realism to how Yi Yi is put together that supports these intentions. Weihan Yang’s photography has a delicate beauty, draping light in thin layers over the scenes so that even though everything looks real, it has just the right polish. Loneliness, both public and private, is often given a wide frame. More than once, we spy a shared moment from outside a café window. Only at important times will we get closer so that the camera may regard the quiet hurt. It’s always a gentle intrusion, and the creative Yang duo often lets the characters hide in the shadows at those moments--NJ in his hotel room, Sherry in hers, Min-Min looking at her face in the window glass. It’s not voyeuristic so much as it is respectful.

The cast also deserves special note. It’s hard to regard most of these people as actors, as these aren’t performances where you can really point to technique or mannerism. Only the more comical subplot with A-Di and his two women seems put-on, something Yang intentionally underlines when A-Di relates his ludicrously embellished story of how he got his money back. The young actors in particular avoid any of the usual tricks and foibles of their age. Kelly Lee manages to give Ting-Ting private, silent aches without resorting to emo whining, and Jonathan Chang’s Yang-Yang is charming without ever being precocious. His eyes drink in the world, but he never vomits it out the way so many child actors are so often called upon to do.

Yi Yi is stitched together with such elegance, the careful structuring is nearly imperceptible. It’s a story with deep resonance, its themes and its situations traversing culture and touching on universal meaning. There is much to rewatch here, reasons to revisit, ponder, and explore. There are no platitudes extended at its end, no epiphanies or even reconciliations, yet the viewer is left with something far more substantial than they might find in a film where the connective tissue is more pronounced. It sweeps by like a breeze, easy and calm, but if you take a look around, Yi Yi has left plenty behind. It’s the unique pleasure of cinema, how seemingly quickly it comes and goes, but how long it really lasts. It’s why we watch movies, why we now let them into our homes. The visceral pageantry makes it feel like we are seeing our own lives reflected in the glass.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Please Note: The screengrabs used here are from the original Criterion standard-definition DVD of Yi Yi, not from the Blu-Ray.

Ting-Ting: “Then who needs movies? Just stay home and live life!”

The Taiwanese film Yi Yi is, in fact, about life, but it also reminds of us why we actually like movies, too. Edward Yang’s 2000 feature has an epic length, but a most human scope. Clocking in at nearly three hours, this family drama takes its time looking around in the lives of the Jian clan. It begins with a wedding and it ends with a funeral, and Yi Yi covers all the ups and downs in between--though really, rather than being pointed peaks and valleys, the graph of this narrative would be more like a wavy line. True life isn’t that sharply defined.

A lot happens in Yang’s opening sequence. The basic relationships are laid out and the various emotional conflicts indicated. A-Di (Xisheng Chen) is marrying Xiao Yan (Shushen Xiao), who is in an advanced state of pregnancy. Apparently, A-Di jilted his long-term sweetheart Yun-Yun (Xinyi Zeng) to have his affair with Xiao Yan, and his mother (Ruyun Tang) has not forgiven him and goes home before the reception. She lives with her daughter Min-Min (Elaine Jin) and her husband NJ (Nianzhen Wu), and the old woman has a stroke while everyone is partying, an event that her granddaughter, Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee), blames herself for. Grandma collapsed taking out the trash, which was Ting-Ting’s job. She fears her bad behavior is why the old woman is in a coma, and if she can be good long enough to earn her forgiveness, Grandma will wake up.

Meanwhile, the Jian men are having women trouble, it’s not just A-Di. NJ runs into his high school sweetheart, Sherry (Suyun Ke), in the lobby of the hotel where the reception is being held. She is visiting from America, where she moved after NJ broke her heart without explanation. Maybe the father’s sins have been passed on to the son, then, and it’s karmic retribution that is causing little Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang) to always get picked on by girls. Yang-Yang is an interesting character, as he mostly stands apart from the rest. His dramas with other kids and the dean at his school are his own thing, and his exploration of new experiences is different than the rest of his family, who are mostly dealing with what they already know. The grandmother’s poor health, for instance, puts her daughter on a spiritual quest and makes Yang-Yang’s sister question her moral health, but Yang-Yang is asking philosophical and scientific questions. He is trying to figure out how it is we look at the world the way we do.

Which, when you think about it, isn’t all that different than what all the others are trying to figure out. How did I get to be this way, and why doesn’t it make me happy? Long after she ponders the pointlessness of cinema, Ting-Ting asks, “Why is the world so different from what we thought it was?” In Edward Yang’s fictional reality, it’s not really an either/or proposition, everything is of one piece. It’s why he named the movie Yi Yi, which literally translates as “One One,” but it’s also meant to be like a band leader counting off before a song. “A One and a Two...” is kind of the official translation, or more like a subtitle. As Yang explains in his press notes, life is about ones and twos. It’s all the same, and all separate, both apart and joined all at the same time. Each new moment can also be a potential new start.

Thus, a spiritual journey can easily run alongside a more logical examination and mother and son can end up in the same place. Or, in one of Yi Yi’s most touching sequences, Ting-Ting goes on her first date ever at the same time her father goes on what is the first date of his second chance. Both nights out are remarkably similar, and they end with heartbreak and confusion. Yet, for all of these coincidences and shared experiences, life itself is seemingly random. Why else, then, would the screw-up brother A-Di stumble into good fortune despite squandering so much, and Ting-Ting have such trouble despite her attempts to be good? Amidst all these criss-crossed romances and bruised feelings, there are no real checks and balances. Things go one way or they go the other. A one or a two.

There are many modern movies one could compare Yi Yi to. In some ways, the dissatisfaction and the potential dangers of the different personal quests remind one of Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm [review]; in how the family works as a unit partially because of how badly the pieces sometimes fit together brings to mind Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Still Walking [review]. Edward Yang approaches his material with more patience and editorial distance than either of those. His work is less stylized than Lee’s and more open than Kore-eda’s. He uses multiple points of view to get at the truth--peering around corners, looking across corridors, and examining reflections to search out what might otherwise not be seen. Young Yang-Yang has a theory that we can only know half of what is real because we can only see what is in front of us. So, he goes around photographing the backs of other people’s heads so they can see themselves as only others can (the DVD cover makes even more sense once you see the film). In this way, the writer/director also seeks out the answers his characters may never find.

Which isn’t to say that Yi Yi is without mystery either. There are some things that Yang isn’t going to put too fine a point on--Sherry’s lonely decision and the origin of the paper butterfly, to name two. Like I said, life is not that sharply defined. The important thing is that the filmmaker doesn’t forget the individuals who stand in this sea of questions, and in so doing, doesn’t allow them to forget themselves.

There is a beautiful realism to how Yi Yi is put together that supports these intentions. Weihan Yang’s photography has a delicate beauty, draping light in thin layers over the scenes so that even though everything looks real, it has just the right polish. Loneliness, both public and private, is often given a wide frame. More than once, we spy a shared moment from outside a café window. Only at important times will we get closer so that the camera may regard the quiet hurt. It’s always a gentle intrusion, and the creative Yang duo often lets the characters hide in the shadows at those moments--NJ in his hotel room, Sherry in hers, Min-Min looking at her face in the window glass. It’s not voyeuristic so much as it is respectful.

The cast also deserves special note. It’s hard to regard most of these people as actors, as these aren’t performances where you can really point to technique or mannerism. Only the more comical subplot with A-Di and his two women seems put-on, something Yang intentionally underlines when A-Di relates his ludicrously embellished story of how he got his money back. The young actors in particular avoid any of the usual tricks and foibles of their age. Kelly Lee manages to give Ting-Ting private, silent aches without resorting to emo whining, and Jonathan Chang’s Yang-Yang is charming without ever being precocious. His eyes drink in the world, but he never vomits it out the way so many child actors are so often called upon to do.

Yi Yi is stitched together with such elegance, the careful structuring is nearly imperceptible. It’s a story with deep resonance, its themes and its situations traversing culture and touching on universal meaning. There is much to rewatch here, reasons to revisit, ponder, and explore. There are no platitudes extended at its end, no epiphanies or even reconciliations, yet the viewer is left with something far more substantial than they might find in a film where the connective tissue is more pronounced. It sweeps by like a breeze, easy and calm, but if you take a look around, Yi Yi has left plenty behind. It’s the unique pleasure of cinema, how seemingly quickly it comes and goes, but how long it really lasts. It’s why we watch movies, why we now let them into our homes. The visceral pageantry makes it feel like we are seeing our own lives reflected in the glass.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Please Note: The screengrabs used here are from the original Criterion standard-definition DVD of Yi Yi, not from the Blu-Ray.

Labels:

ang lee,

blu-ray,

Edward Yang,

Hirokazu Kore-eda

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)