This may sound strange or even reductionist, but I think Japanese director Koreyoshi Kurahara's style is most easily summed up via his credits sequences. The films in the boxed set

The Warped World of Koreyoshi Kurahara, the 28th entry in Criterion's Eclipse series, come from different genres and have varied tones and styles, but the filmmaker's approach to the titles, with one exception, remains consistent. After an introductory scene, Kurahara carefully chooses a moment to freeze the image, introducing the name of the picture on top of this still, capturing his characters in flux. Sometimes it's serious and shocking, sometimes it's hilarious and humiliating. Then the rest of the credits roll with the image stopping and starting, the text juxtaposed with the isolated moments, working with the music to indicate the emotional weather patterns inside the atmosphere we are now entering. These sequences are always stylish and never dull, and Kurahara often closes his films in a similar matter, reminding us at the outset and at the finish that this is cinema, it is artifice, even as he asks us to step into a realm that is entirely his own.

Kurahara was a contract worker at Nikkatsu studios starting in the late 1950s; he continued making films well into his later life, though regularly altering his style in unpredictable ways.

Warped World picks up in 1960 as the director experienced an artistic sea change, coming into his own through standard genre pictures, eventually exploring his personal vision using popular stars in vehicles that look familiar when taken at face value but turn out to be stranger and more unique than they initially appeared. Kurahara's films tend to follow characters who have become trapped and are desperate for a way out. Some of them are reserved and calculating, others are agitated and rebellious. Not all of the quintet represented here hit with the same accuracy, but part of the point of the collection is to illustrate how versatile Kurahara was. The scattershot approach means there likely won't be a bull's-eye every time, but generally, he gets close enough.

The Warped World of Koreyoshi Kurahara kicks off with a bang.

Intimidation (1960; 65 minutes) is a tight crime thriller, a story of blackmail and double-crosses that is sometimes called the first Japanese film noir. (As always, the use of the tag is debatable; I think Hitchcock's

Rope

, or

his TV show

, is a more apropos reference point.) Bank manager Takita (Nobuo Kaneko) is heading to a promotion at the main branch--coincidentally, run by his father-in-law--when a local gangster (Kojiro Kusanagi) threatens to expose some bad loans he extended himself unless Takita pays him 3 million yen. He suggests Takita rob his own bank, since no one will ever suspect the boss of thieving. Seeing no way out, Takita tries to pull of a late-night heist. Despite his best efforts to keep him out of it, Takita's assistant Nakaike (Akira Nishimura,

The Bad Sleep Well [

review]) gets tangled in the burgling. Nakaike has been under Takita's thumb his whole life. The other man jilted Nakaike's sister, Umeha (Mari Shiraki), to marry Kumiko (Yoko Kozono), who was Nakaike's girlfriend at the time. Had Nakaike married her, he'd be in Takita's professional position; instead, he warms the man's sake. Insult to injury, Takita is still having an affair with Umeha. We see a predatory chain running through this community: Takita may be intimidated by a crook, but he has been intimidating Nakaike in one way or another their entire lives.

When you think about it, that's a lot of backstory for a movie that barely crests an hour in length, but Kurahara has wound these things so tight, you'd barely notice. The screenplay is by Osamu Kawase, from a story by Kyo Takigawa, and Kurahara stages their material with precision. What at first appears to be mannered social drama quickly gives way to pulpy twists and turns, with the actual bank robbery staged in nail-biting silence, like a more direct take on Dassin's safecracking in

Rififi [

review]. From that point on, the change-ups come pretty quick. Pardon the referential joke, but it's all downhill from there. Kurahara and cinematographer Yoshihiro Yamazaki compose elegant shots, arranging the actors throughout the scene to emphasize their hidden relationships, while using tight close-ups to underline their anxiety.

Intimidation is a sophisticated genre exercise that will keep you guessing right up until the memorable final moments. It's a movie where no one gets what they want, where all selfish intentions yield empty results, and innocence is as ephemeral as a flame from a lighter.

The same year that Kurahara made

Intimidation, he also made the juvenile delinquent picture

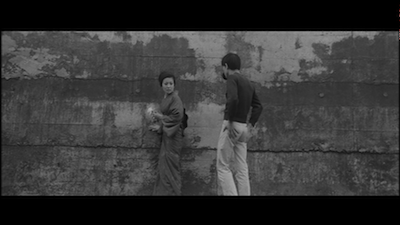

The Warped Ones (1960; 75 minutes). Part of the "Sun Tribe" subgenre chronicling the frustrations of post-War Japanese youth,

The Warped Ones is a semi-formless picture, its verité style mirroring the aimless day-to-day of its criminal subjects, bookended by those energetic freeze frames to emphasize the feeling that these are stolen moments, snapshots arrested in time.

Tamio Kawachi, a regular participant in Seijun Suzuki films, stars in

The Warped Ones as Akira, a petty thug and pickpocket. Akira appears to be in a state of constant agitation. He is always overheated, always squirming; he looks like he would claw off his own skin if he could. He hangs around with a prostitute named Yuki (Yuko Chishiro), and the pair of them gets arrested when a straight-laced newspaper reporter (Hiroyuki Nagato) helps the cops pull a sting on them in the jazz club. When Akira gets out of prison a month later, he has a new friend, another crook named Masaru (Eiji Go).

While joyriding in a stolen car, the trio run across the snitch and his girlfriend, an abstract painter named Fumiko (Noriko Matsumoto). They kidnap Fumiko, and Akira rapes her. Telling her where the police station is after he is done is the closest the jerk gets to compassion, and it suggests that maybe she has gotten under his skin in some way. When she tracks him down weeks later to tell him she has gotten pregnant, he rejects her, but then shortly after, he seeks her out. It's an emotionally harrowing push-and-pull. He doesn't want to be with her, but he won't stay away from her. Things get even more complicated when Fumiko encourages Yuki to seduce the reporter so that he'll feel the same shame she feels; her intention that if he is also sexually abused, they will be equal again, but that backfires. (Men are dogs, y'all.)

The Warped Ones' jumpy narrative leapfrogs over customary transitions, cutting from scene to scene without much caution for how it all connects together. Time is elastic. This could be one long day, or it could be several months. On one side of the social register, the characters don't express themselves, they don't know how, but the way Kurahara and screenwriter Nobuo Yamada show Fumiko's pretentious art friends behaving, the filmmakers don't have much respect for the hoity toity, either. It's one of the best scenes of the movie. Akira wanders into Fumiko's party and is immediately humiliated by her friends, who view him as a living art exhibit, an example of a primitive man wandering the modern streets. (You know, like Kramer in that one episode of

Seinfeld.) They laugh at him with the same cruel abandon that he and his pals laugh at the misfortune of their victims. In fact, despite the harsh twists of fate that follow, that laughter keeps going, building to a maniacal pitch (alongside their increased disregard for human life) in the film's final shot. It's framed from a god's eye point of view (a stylistic trademark of Kurahara's), as if to say life is absurd, it will always be absurd, and Akira can toss as many guffaws to the heavens as he can muster, but the heavens will never answer.

[Note: The credits and liner notes on the Warped Ones box suggest that the artist character is Yuki and the prostitute is Fumiko. Indeed, all articles on the film, including the IMDB and Wikipedia entries, say the same thing. The dialogue and onscreen text in the actual film has the names switched, however, so I have followed what I saw and heard, and have decided that the actresses attached are correct for each name based on Yuko Chishiro's return to the role of Yuki in the later film Black Sun.

The 1964 film

I Hate But Love (105 mins.) seems as far away from

The Warped Ones as you can get, but though the romantic comedy appears on the surface to follow a standard line, it's actually extremely off-model in terms of genre expectations.

It begins like any number of 1960s love stories, with two career-minded lovers juggling work and romance and failing to find a balance. Daisaku Kita, played by matinee idol Yujiro Ishihara, is a popular media personality who hosts a TV show that finds the true stories behind the most intriguing classified ads of the day; his manager, Noriko (Ruriko Asaoka), builds him a packed schedule day in and day out, but never fails to book time for their personal engagements, just the two of them. The business partners have been dating for exactly two years--or as Noriko counts it, 730 days--but their passion is waning, largely because they have been denying it. Wooing is fine, but hands off, buster!

Like I said, this all plays like a glossy Hollywood love story. Even the zippy music by Toshiro Mayuzumi (

Reflections In A Golden Eye

) would fit right in on the MGM lot, soundtracking the latest coupling of Doris Day and Rock Hudson.

I Hate But Love takes a strange turn, however, when the frustrated Kita impulsively agrees to go on a cross-country road trip to fulfill the wish of one of his news subjects. A long-distance love affair between an average woman (Izumi Ashikawa) and a country doctor is about to bear fruit in an unusual way: the woman has saved up to buy the doctor a jeep so he can help more sick people who might not have access to health care otherwise, all she needs is someone to volunteer to drive the vehicle to the mountain village he calls home. Eager to prove that love is real and affirm his own humanity in the process, Kita jumps behind the wheel. Seeing it as career suicide, Noriko chases after him. What follows is a cross-country journey on which the philosophical implications are only outweighed by the media circus that erupts around it. The farther Kita goes, the more fraught his journey becomes; as he grows more determined, Noriko gets more frazzled. It all builds to an oversized climax that has ironic consequences and surprisingly affirmative results.

I Hate But Love is well done, with solid performances from the leads and an assured directorial vision. It's the one movie in

The Warped World of Koreyoshi Kurahara to be shot in color. Yoshio Mamiya, who also was DP on

The Warped Ones, is behind the camera again, and he makes the best of both real locations and rickety rear-projection to give life to this absurd road trip.

I Hate But Love not only reteams him with Kurahara, but it also puts the director back together with Ishida and Asaoka; they made the wildly successful

Ginza Love Story that same year.

I Hate But Love would prove a big hit.

Yet, I have to admit, I didn't enjoy it all that much. The comic tone at the start of the picture seemed contrived and outdated, while the more serious middle portion struck me as disjointed and straining credibility. That said, the outlandish mountaintop finish kind of makes it all worth it. Though you can likely guess what happens to the central couple, there are several unexpected twists in the final few minutes that definitely prove

I Hate But Love to be a rom com of a different stripe.

Tamio Kawachi, star of

The Warped Ones, returns for

Black Sun (1964; 95 mins.), and so does the anarchic tone. It's a sequel of sorts, featuring analogues of the characters if not the exact same individuals. Whereas the earlier film ended in howls of laughter, however,

Black Sun closes with a primal yowl, a sound that mixes both the exhilaration of freedom and despair at its cost.

Kawachi is still a jazz lover and a car thief, but he's not nearly as restless or angry as his younger version. Now he goes by the name Mei and squats in the condemned husk of a Catholic church. Its owners keep threatening to tear it down, and he has replaced the religions icons with photos of great jazz musicians. When Mei isn't stealing cars, he's digging up salvage to buy records. The opening of

Black Sun shows him exploring a junkyard. The bombed-out post-War wasteland could just as easily double as a post-apocalyptic landscape, a parallel that is likely intentional. Kurahara's film, including its evocative title, has a doomsday aura around it. Nuclear power plants are visible in the distance. It's both of its time and slightly outside of it. The ruined buildings serve as a constant reminder of the tragic end of World War II, as do the occupying American soldiers that patrol the streets. It's a bit ironic, then, that Mei has embraced one of the popular art forms of the occupiers. Entertainment and junk culture is the greatest weapon of modern colonialism.

Then again, African American musical traditions, be it jazz or rock-and-roll or hip hop, have always had greater political and social significance, something that Kurahara, working again with a script by Nobuyo Yamada, is putting to use in his story. It's rebel music, the anthems of outcasts, and one of those outcasts will change Mei's life. Chico Roland plays Gill, a black soldier who is accused of having gunned down a white serviceman. We don't know if he's guilty, he insists he's not and that the greater "they" are out to kill him. He shows up at Mei's squat with a machine gun and a wounded leg. Mei is excited to meet a real black American, but the language barrier and Gill's desperation put the two at odds. Gill bullies his hostage until the tables turn; Mei gets the gun, and in a bizarre sequence, paints the American's face white and his own face black. Disguised, they leave their hiding place and go to Mei's favorite jazz club, where he shows off Gill as his "slave."

This topsy-turvy relationship is a distorted foreigner's version of

The Defiant Ones

. The scenario not only speaks to race relations in the 1960s, but also to the tension between Japanese citizens and the Americans, who are squatting in Mei's ruined country just as much as he is living in one of their abandoned churches (a harsh symbol when you consider all the implications). When Gill and Mei hit the road and realize that there is no turning back, the military police have identified both of them and their car, the two men begin to come together, finding that their common bond is that they are being abused by the same white institutions. This all leads to yet another of Kurahara's surprising conclusions. I don't want to give away what causes that scream I referenced earlier. I guarantee, you won't see it coming.

Kawachi is once again very good, though his performance in

Black Sun is not nearly as hyperactive as in

The Warped Ones. Despite his habit of racial profiling, Mei is essentially a good guy with a genuine enthusiasm for jazz and black culture. He has a greater range of emotions than Akira had: sarcastic, playful, angry, distraught. Unfortunately, Chico Roland is a terrible actor, and his unconvincing performance is hampered by some of the worst ADR this side of an Italian spaghetti western. For as much as his onscreen actions are exaggerated, his vocal performance cranks it up several notches still.

The true MVP of

Black Sun is the music. Toshiro Mayuzumi, who so effectively mimicked Hollywood's most ebullient orchestration in

I Hate But Love does just as well here crafting a jazz score. Granted, he is helped by having the Max Roach Quartet to record the tunes. (In the credits sequence, Mei goes into a record shop and orders the soundtrack by name.) The bebop not only adds bounce to the more energetic scenes, but in the final act, creates an emotional mood, conveying the sadness and fear of

Black Sun's doomed fugitives.

Kurahara shifts gears again for the last film of the series,

Thirst for Love (1967; 99 mins.), which also happens to be his final effort as a Nikkatsu regular. This somber, erotically charged film is an adaptation of a novel by infamous Japanese author

Yukio Mishima, and it stars

I Hate But Love's Ruriko Asaoka as Etsuko, a young woman trapped in a bizarre family after her husband's unexpected death. Some time has passed, and Etsuko's new role in the clan is as her father-in-law's live-in mistress. Her sleeping with the old man (Nobuo Nakamura) might be out of place in another family, but the whole set-up is dysfunctional. Etsuko's brother-in-law (Akira Yamauchi) lives at home with his wife (Yuko Kusunoki), sponging off his father and proud of it. He is sterile, and so has no kids, and he clearly has a thing for Etsuko.

She, on the other hand, is obsessed with their underage handyman, Saburo (Tetsuo Ishidate). She is flattered when she catches him staring at her from outsider her room, angry when he doesn't wear socks she bought special for him. The sexual tension is loin deep, and everyone must wade through it as they would a swamp. The weight of all this desire becomes too much to bear when Saburo impregnates another servant (Chitose Kurenai) and the family meddles in the affair, making plans for their hired hands with little regard for what they may actually want for themselves. The class divide being what it is, they mostly get away with it, too, resenting any resistance. Money is the only weapon either side has: giving it, taking it,

extorting it.

Ruriko Asaoka is an alluring screen presence. She has an austere beauty and an uncanny ability to express hidden desire covertly.

Thirst for Love smolders like an

E.M. Forster or

Edith Wharton adaptation. The inexpressible is always on the verge of coming to the surface, the act of denial is more charged than any succumbing to impulse. Kurahara molds his style to the material. This is his quietest film, and though the aesthetic choices aren't as gonzo as previously, they are no less bold. The director, who co-wrote the script, creates an authorial persona, maintaining a certain distance from the material while also trading on the interior lives of his protagonists. Voiceover duties are swapped between different characters, and sometimes the narration appears to be spoken by the director himself (a god's eye view of a different sort). Kurahara and Mamiya often abstract the visuals from the spoken word, showing landscapes at a distance or bodies close up, almost as if divorced from what is being said aloud. Other times, onscreen text relates what can't be shown.

In

Thirst for Love, instead of using freeze frame images for the opening credits, Kurahara lingers on Asaoka's naked body, isolating different portions--her stomach, her neck, her shoulder--with a fetishistic eye. Still images appear elsewhere, but in this film, they are the province of memory. Our only glimpses of Etsuko's life with her late husband come via a series of photographs put together in a style reminiscent of

Chris Marker. Kurahara also uses this device for present moments of extreme passion, restraining his mis-en-scene as if to make up for Etsuko's lack of the same. He also injects color, using bright red screens to show how hot her lust burns inside of her.

In keeping with Mishima's literary themes, Etsuko's denial of the self is wished for nearly as much as she considers it a torment. She inflicts physical punishment on herself, and also maneuvers to have the situation with Saburo blow up in her face. It may seem like a bizarre route to take, but it ultimately liberates her from the grip of her married family. This is something she has in common with all of Kurahara's protagonists, they all have some kind of arduous metamorphosis prompted by an untenable living situation. Be it the overlooked clerk in

Intimidation or Akira/Mei limited by his squalor, or even Daisaku Kita in

I Hate But Love being hedged in by fame and exiled from his love by his regrettable arrangement with Noriko, the journeys of struggle that comprises their narratives have a real destination. Whether what they find there is good or bad is debatable in some cases, but all of these characters have moved or changed position in some manner. In Etsuko's case, she literally moves on, stepping at last out of the black-and-white and into the color. Her world has indeed warped, and now it's something completely new.

The Warped World of Koreyoshi Kurahara - Eclipse Series 28 lives up to its title. The five movies here really do show a self-contained image, like a Bizarro World inside a cinematic bell jar. Kurahara's vision of post-War Japan is one where an occupied people struggle with class structures and a lack of opportunity, resorting to drastic measures and selfish gestures. It's a crazy scene, start to finish, and you'd be hard-pressed to find anything quite like it on either side of the Pacific.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVD Talk.