Halloween is here, and I hit my goal for one horror movie a week for October. Go me!

In addition to those reviews, here are some other movies I was able to scare up reviews for in the past month:

IN THEATRES...

* Ashes of Time Redux, the restoration of Wong Kar-Wai's martial artist stunner. I was very excited to see this, as you will likely read!

* Blindness, a take on the post-apocalyptic genre where a disease strikes people like Mark Ruffalo and Gael Garcia Bernal blind, while leaving Julianne Moore with her sight so she can be Queen. I'm still torn on this film, and was almost going to rate it at "Rent It" right up until posting time. I am still struggling with whether or not its doldrums overpower the good bits or vice versa.

* Happy-Go-Lucky, the new Mike Leigh dramedy with a stellar performance from Sally Hawkins as the eternal clown.

* Let the Right One In, a Swedish vampire film that really gives the genre a whole new lease on its undead life.

* Rachel Getting Married, Jonathan Demme's unbalanced movie about family nearly stifles great turns from Anne Hathaway and Rosemarie DeWitt as sisters trying to deal with their past as they move into the future.

* W., Oliver Stone's perplexing biopic of George W. Bush.

* What Just Happened, a Hollywood tell-all that tells nothing, despite some good work from Robert DeNiro. Based on a book by Art Linson, the story has been defanged beyond recognition.

ON DVD...

* Chaplin: 15th Anniversary Edition, the flawed biopic stays memorable thanks to Robert Downey, Jr.

* Flight of the Red Balloon, wherein one of my favorite contemporary filmmakers, Hou Hsiao Hsien, pays tribute to one of my favorite children's films.

* Ludwig, the gigantic Luchino Visconti biography of the mad king of Bavaria. This took a while to get through, which is why I slowed down some. (Plus, I have some big sets I am starting, too.)

* Mondays in the Sun, a Javier Bardem vehicle about men struggling with unemployment in Spain. A surprisingly meaningful drama with good characters and a balance of humor.

* The Picture of Dorian Gray, the chilled 1940s adaptation of the Oscar Wilde classic. Directed by Albert Lewin.

* Six in Paris, an anthology of French New Wave directors tackling different neighborhoods in the City of Light. Produced by Barbet Schroeder, and featuring segments by Rohmer, Chabrol, and Godard.

* Touch of Evil: 50th Anniversary Edition, a two-disc examination of Orson Welles' troubled noir classic.

* The Unforeseen, a dreamy, soulful documentary about urban sprawl and its effect on Austin, Texas. Co-produced by Robert Redford and Terrence Malick.

* Warner Home Video Western Classics Collection, collecting six cowboy movies from the Warner Bros. vaults, only two of which--the Rod Serling-penned Saddle the Wind and the Gregory Peck-vehicle The Stalking Moon--are really worth it. Also features Anthony Mann's Cimarron, William Holden in Escape from Fort Bravo, and Richard Widmark as another charismatic bad guy in The Law & Jake Wade.

Friday, October 31, 2008

Thursday, October 30, 2008

THE BLOB - #91

In all honesty, I don't know what to think of The Blob. Just how seriously am I supposed to take the 1958 sci-fi horror teensploitation flick? Sure, by today's standards, it seems campy, but that doesn't mean it wasn't made with absolute earnestness. The Burt Bacharach-penned title song might make it seem like it's all supposed to be a goof, but then again, Paramount commissioned the tune to be a soft opening so that audiences wouldn't get creeped out too soon. I've read some theories that suggest that the Blob itself was meant to be a metaphor for communism, a creeping mass with a reddish hue that consumes everyone in its path, growing larger, erasing identities, and leaving no trace of the individuals it swallows. It also could be seen as 1950s conformity, and the teenagers who resist the alien monster are resisting assimilation into square culture.

Personally, I would lean more toward the Blob being adolescence itself, a quivering mess of hormones and lust, an icky and oily embodiment of teenage anxieties. It attacks the older generation first, leaving the juveniles to sound the alarm, but their twitchy slang makes it impossible to spread the word to an adult world that either can't or refuses to understand them.

That's what I'd likely say if I thought more of The Blob, but the truth is, I really don't think much of it at all. I like B-movies as much as the next guy, but The Blob is funnier in the abstract than it is in execution. I like that there is a silly movie like it out there, but I'm not necessarily all that eager to sit through it. As a horror movie, it's not that scary. It's a thriller without thrills, clumsily paced and poorly acted. Steve McQueen went on to better things from here, but he was nearly 30 when he made the movie and he's not very convincing as a teenager. His stuttering delivery is so overly method, even Stanislavski would blush. Put him in a red windbreaker and I'd believe he was parodying James Dean rather than delivering a legitimate performance.

The story here is simple: a meteor crashes in the mountains, and when it cracks open, a gelatinous substance emerges. It attaches itself to the old man who finds it, sticking to his hand. He runs from the site of impact in terror and nearly gets run over by Steve Andrews (McQueen) and his date for the evening, Jane Martin (Aneta Corsaut). They take him to the local doctor, but soon the substance takes over the old man's entire body before moving on to the doctor and his nurse, and then oozing into town, where it goes after all the tasty humans at the movie theatre, grocery store, and other places. Steve and Jane stand against it, alongside the few adults that believe them (notably, Lieutenant Dave of the local constabulary, played by Earl Rowe). Naturally, they succeed, as this isn't an apocalyptic picture, but I'll leave the how for you to discover, just in case you ever do watch The Blob. I'd rather not suck all the fun out of it--what little there is.

I'm a firm believer in B-movies as camouflage for more subversive cargo. I'm all for seeing sci-fi and horror as carrying greater social messages. In fact, all the theories above can also be applied to Don Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers

One of the more famous scenes in The Blob is when the monster invades the projection booth of the town movie theatre, snuffs out the projectionist, and then halts the midnight spook show everyone is watching before sending them running. It's meant to be self-reflexive, to make viewers wonder if maybe the theatre they are in is in danger. I find it self-reflexive in another way. The Blob certainly wouldn't be the last time a movie was built around a special effect, as if that alone was enough and story and other needless accoutrements could be left by the wayside. In these days of computer-generated high-concept celluloid, a metaphorical Blob fills up many a projection booth. In the long run, most of these movies will end up forgotten, and it baffles me why The Blob has managed to avoid the same fate. The Blob doesn't consume me with its chills, rather it just leaves me cold.

Friday, October 24, 2008

CARNIVAL OF SOULS - #63

The 1962 black-and-white horror feature Carnival of Souls is a ghost story of a classic variety. It's the kind of mounting chiller that comes from the oral tradition, begging to be told around a campfire or with a flashlight tucked under your chin. That it was made by a group of guys using equipment from the industrial film company they worked for in Lawrence, Kansas, probably only adds to that homegrown urban legend feel. Like the best of these kinds of stories, it is steeped in convention, yet its telling is so involving, one forgets what one knows about such tales and is swept away by fright.

Carnival of Souls begins unassumingly on a small town road where a car of guys challenges a car full of three girls to a drag race. On a rickety old bridge too narrow to hold both vehicles, the ladies careen over the side, sinking into a sandy river. Hours later, the police and rescue teams can't find the car, but one of the ladies inexplicably appears on a muddy jetty, soaked to the bone but otherwise unharmed.

Mary Henry, played by otherwise unknown actress Candace Hilligoss, is an organ player who had been scheduled to leave Kansas for Utah two days later. A position tickling the pipes at a church awaits her, and she sees no reason to call off her plans because her two friends have died. Mary is a bit of a cold fish, which is maybe how she survived the icy river. Or maybe she took a knock on the noggin and that's why she's suddenly so moody. One minute she wants to be completely left alone, the next she is cheery and wants to chat and hang out.

Driving alone at night, Mary heads for her new home, but once she crosses over into Utah, strange things start to happen. The image of a ghoulish man appears in the passenger window, seemingly defying all laws of physics. As soon as she shakes off this hallucination, he appears again, this time standing in the road in front of her. She swerves to miss him, driving into a ditch, a dangerous mirror of her previous auto accident, but when she looks back to the road, the man is gone.

Along the same road, Mary sees a strange building off in the distance. A gas station attendant informs her that it's an abandoned carnival pavilion, and it's been boarded up for years. Mary feels a strange attraction to the pavilion, and she even tries to go inside it the next day when out on a drive with her new boss, the church minister (Art Ellison). He won't let her go inside, though, because it's against the law. Mary says she will have to return another time then, and the viewer has a sinking feeling that she will. The preacher's admonition was intended to enforce the laws of man, but the implication could be that this place violates the laws of God, as well.

The narrative of Carnival of Souls is exclusively the tale of Mary trying to figure out what is happening to her. The latter day spook in the tailored suit she saw on the road keeps following her, appearing in her boarding house and even in the church, always moving toward her like he wants to tell her something. The increasingly nervous Mary also starts to have other hallucinations where the world goes quiet. She can see everyone else, but they can't see her; she can hear herself speak and her footsteps on the ground, but she can't hear anyone else talk. She even goes into a trance while playing the organ, seeing the zombified man and a host of other specters rising from the inky river near the carnival pavilion, where they engage in a ghostly ball. This scene, like the bulk of Carnival of Souls, is set to the morose organ music composed by Gene Moore. It's a smart stylistic choice, invoking cultural memories of carnivals, religion, and gothic tales of the macabre. It also has a psychological oppressiveness that ties into the fact that Mary is an organist herself. It seems to rise out of Mary's own psyche, an inescapable expression of her fear.

Candace Hilligoss is the secret weapon of Carnival of Souls. Without her, the movie wouldn't work. A lanky blonde, she looks like a prototype for Anne Heche. She is very good at conveying confusion and panic. Unable to figure out what is happening to her, she turns to a variety of people--the minister, the creepy neighbor in her boarding house (Sidney Berger), the local doctor (Stan Levitt)--all of whom don't take her plight very seriously. They are the kind of annoying people who think sadness can be cured by a stranger telling you to smile. They all think she just needs to socialize more, though how they express this opinion is more telling than Mary realizes. Catching her playing a manic dervish on the church organ, the priest accuses her of having no soul. So, too, does Mary's would-be suitor decide Mary is frigid and accuse her of being an arctic tease. These all foreshadow the final reveal, when we finally learn Mary's true fate, when her pursuer can deliver his good news.

Mary's spectral stalker is an iconic horror figure. Simple white make-up, a black suit and tie, and a wide-eyed look are all the silent fiend really needs to give viewers the creeps. Played by the director and producer, Herk Harvey, he is the simplest of villains, doing very little but sparking the audience's imagination. As in the best scary movies, what we think might happen is just as integral to the mood of fear as what actually does happen. In the Criterion booklet with the DVD, screenwriter John Clifford says he wrote the screenplay sequentially, never knowing where it was going until he got there. The only real trick he had up his sleeve was making sure that Mary stayed totally alone, that no one believed her or helped her in any great way.

Clifford's writing process is indicative of the production as a whole, with a crew of people who had never done this kind of thing before just grabbing some cameras and going and doing it. Carnival of Souls was shot in three weeks for $30,000, and though some of the acting and the storytelling can be a little clumsy, the modesty of the endeavor never really shows. This is down to the masterful photography of Maurice Prather than anything else, even more than Gene Moore's music or Herk Harvey's dark-eyed bad guy. Prather's eerie black-and-white compositions have a chilly beauty. He begins with the opening credits, composing a naturalistic mis-en-scene featuring the deadly river that swallowed Mary and her car, showing us a world that is real and familiar. This makes us accept what we are seeing so that we will go on accepting it even as the movie takes a turn into the dark and sinister. Using the abandoned Saltair amusement park on the Great Salt Lake was a stroke of genius, and Prather's industrial work clearly prepared him to capture its worn-down surfaces and shadows.

This low-budget exercise in mood doesn't really have any jump-out-of-your-seat shocks, but that's okay, it's more about taking you deeper into its heroine's dreadful dilemma. I actually found it more involving watching it this time than I did when I first got this DVD a couple of years ago. While we would expect more contemporary indie horror films to go for the splatter (think Cleaver, the movie Christopher made in The Sopranos), Carnival of Souls reaches back to more classic scarefests, the kind that uses less to frighten us more.

By the by, the cheeky references to Mormonism and the almost missionary-like doggedness of the mysterious man's pursuit of Mary was intentional, but I don't think the filmmakers intended any connection, so I don't think it deserves a greater focus than I've given it. I fully admit it's kind of a cheap joke, based solely on the fact that the film is set in Utah. Though no denomination is given, the minister whom Mary works for is wearing a priest's collar, which I don't believe is the uniform of the leaders of the LDS church, and he in no uncertain terms is imploring Mary to accept his version of heaven. Logically, this would mean the alternative is hell, but given how other Christian denominations view the Mormon faith, I could definitely see someone trying to bend Carnival of Souls into some kind of propaganda. "Come to the right church, Mary!" Personally, I'm all for personal choice, and whatever you choose, hey, that's fine with me. No offense is intended, it's just something that popped into my head while viewing the picture.

Monday, October 20, 2008

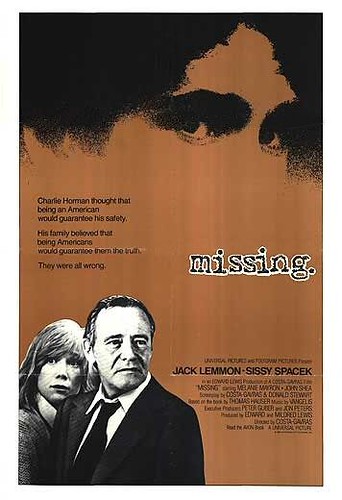

MISSING - #449

The early 1980s was a weird time in my movie-going education. My family did not go to movies for most of my early childhood, a religious embargo I managed to break in 1979 when a seven-year-old me whined his way into getting to see The Black Stallion

As a matter of fact, Mom, I was.

Anyway, once this barrier had been shattered, all bets were off, and we went to the movies pretty much every week. My father was a master theatre hopper, and so an outing to the movies usually involved seeing two or three movies in a day, sometimes all of us going to completely different films. I chronicled some of this in my review of Hopscotch, one of those movies we saw that I probably shouldn't have seen at my age. It makes for a strange variety of nostalgia, these formative years where I could see Kurt Russell in both a revival run of The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes

Anyway..., of movies that I saw but maybe shouldn't have, I think they could be classified in three categories. First were the movies like Silkwood that I liked but probably didn't really understand why. Second were the movies that I knew were terrible and even kind of offensive, such as De Palma's Scarface

One of these third beasts was Costa-Gavras's 1982 political drama Missing. I was ten when it was released, not yet ready to absorb the entirety of what this extremely complex docudrama had to say. I've always remembered seeing it, though, and I even remember being bored while we were watching it, maybe even walking out or going to sleep. Yet, just remembering that must hold some significance. This thing I could not understand had obviously left an impression. Why else would I, twenty-six years later, still remember the grainy black-and-white newspaper reproductions of the movie poster from when we were going through the listings to see what was playing? How else do you explain that I had three images from the movie lodged in my brain? Jack Lemmon holding Sissy Spacek close, helicopters, and John Shea posing for a photo by the beach--all three of these would come to mind any time the subject of Missing would come up.

I admit to feeling a little electrical charge when I first saw the announcement that Criterion was releasing Missing. After all this time, I would sit down with this highly lauded film and relive the experience that had so baffled me as a ten-year-old boy. It's impossible to explain why I had waited all this time to see it again. Things just have a habit of staying out in front of you, y'know?

I'm pleased to say up front that my mind was effectively blown. Missing is a phenomenal motion picture, on par with iconic intelligent thrillers from the 1970s like All the President's Men

Good journalistic storytellers know that there is an inherent drama in real life that is just as reliant on coincidence and narrative convention as anything invented from whole cloth. The screenplay for Missing was written by Costa-Gavras, Donald Stewart, and John Nichols, working from a book by Thomas Hauser, and the writers smartly see that the drive of their two very different characters makes the personal journey they undertake in searching for Charles just as fascinating as the investigation itself.

Charlie and Beth were young idealists living in Chile for no other reason than they enjoyed the way of life down there. Though left-leaning in their politics, neither were political activists. Charlie only really became caught up in what was happening in Chile because he happened to be there, either the right place at the right time or the wrong place at the wrong time, depending. As soon as Ed Horman arrives in Chile a couple of weeks after Charlie has disappeared, it's obvious that father and son couldn't be more different, even without them ever having a scene together. Ed is a devout Christian Scientist who believes in God and country and doesn't understand why his son would live in South America, living as if he were poor and not continuing on the life path his family always thought he was meant to follow. Ed doesn't believe Beth's theories about Charlie's abduction, he's more inclined to trust his government and even accepts the explanation that maybe this is a stunt Charlie is trying to pull in order to embarrass the U.S.

As a Christian Scientist, however, Ed has one core belief that eventually puts him and Beth on the same page. When he is asked to explain the fundamentals of his religion, Ed boils it down to having faith in the truth. The common goal of both father and wife is to find out what happened to their son and husband, and the further they go into the investigation, the more their beliefs merge.

From an acting point of view, Lemmon has the meatier role. His character is the one who is going to change the most, who is going to have the foundations of his beliefs rocked. It's probably no coincidence that he confirms his change immediately following an earthquake, the shaking hotel reminding him enough of his own mortality and dislodging his stubborness to such a degree that he feels he has to apologize to Beth. It's not a showy transformation, though, it's one that happens little by little. Lemmon already had a natural hunch at this time, but as Ed grows increasingly defeatist, it becomes more pronounced. The actor mainly plays him as soft-spoken when dealing with authority, but more tenacious when talking to Beth. It's the tenacity of a father, however, and when he realizes that his attentions are misplaced, we see the mannerisms reverse. Ed becomes a verbal attack dog when stonewalled by the U.S. embassy in Santiago.

Ed's transformation is not just in how he views the world, though. There is a far more subtle shift in the writing. He also changes as a father. Just as he is at first angry with Beth, he is also angry with his son, not understanding how his little boy became a man so far from the family's way of things. In trying to figure out what happened to Charlie, Ed starts to see how his parenting has really influenced his child. More than once someone points out a gesture that the two share, or how they each behaved in a similar situation, and each time it closes the gap. The father discovers that the fruit stayed much closer to the tree than he had ever thought, and the same tenacity for the truth that has brought Ed searching for his lost child is also why the powers that be wanted the child lost in the first place.

Missing proved to be a real political hot potato at the time of its release. Though the film gets no closer to the answers than Ed and Beth did in 1973, it does lay out a complex map of events that don't seem so far fetched now that we know more about the Pinochet government and the U.S. connections to the same. I don't think it would be a stretch at all to draw analogies between what Nixon and his people may have done down in Chile back then and what the current administration has also pursued in its involvement in regime change in the Middle East. More importantly, though, I think Missing rather sharply defends a particular strain of patriotism that current political rhetoric would have us believe is somehow un-American. From where I sit, both Charles and Ed Horman are the best kinds of patriots, the ones who love their country enough to call it out on its shame not to detract from but in order to defend it principles. When Ed tells the people who have filibustered him that he is going to take every action to make sure the word gets out about what they have done, one of the U.S. consuls says to him, "Well, I guess that's your privilege." In response, the movie version of Ed memorably declares, "No, that's my right! I just thank God we live in a country where we can still put people like you in jail." Inherent in that statement is the core belief that United States, regardless of the wrong turns it may take, is a nation that is always better than the bad decisions of the most misguided or selfish of its people.

Of course, sitting in a theatre at age ten, I wondered more about when Missing would be over than I pondered what Costa-Gavras was telling me. (The director has himself said that Missing stands as a testimonial of the power of free speech in America, and is also swayed by the individual's personal beliefs or investment in seeing justice done.) Even so, whether or not I was conscious of it, I think the message still got through, at least enough to leave me with the impression that eventually revisiting the movie would be important. That's the true power of a piece like this, and the true validation of Ed Horman's faith: the truth will always get through, regardless of how many shadowy hands try to hold it back, as long as the rest of us demand it be told.

Costa-Gavras

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

JIGOKU - #352

Of all of man's fears, there is perhaps no greater than the fear of death and what comes after. While some humans fear that there is nothing on the other side, the greater dread is that there is more after this life, both a paradise and a wasteland, and despite our best efforts, we might end up in the wasteland. Even those who believe there is nothing awaiting them must have the occasional nagging worry that they are wrong and by choosing wrong, will be doomed to eternal punishment.

Many artists have tried to visualize what Hell would be like. The paniters Hieronymus Bosch and Francis Bacon are probably two of the most well-known and highly regarded, and I could see their influence in Nobuo Nakagawa's 1960 film Jigoku (Hell). I also could see touches of classical images from Japanese folklore, the odd stylings of their ghost tales and even the traditional garb of feudal lords. Enma, the King of Hell (Kanjuro Arashi) looks like an old shogun filtered through kabuki theatre and the worst drunken Halloween you've ever had.

Jigoku is a B-movie morality play, ripe with melodrama but short on histrionics. That latter qualifier is not necessarily a good thing. There is a little too much Asian reserve in the first half of the movie, which is meant to set up the colorful lives of Nakagawa's sinners so that by the movie's final act, when they have all died and gone to Hell, Enma will have something to punish. The screenplay, co-written by Nakagawa and Ichiro Miyagawa, borrows all of its scenarios straight out of soap operas, but it's staged like the most serious of social dramas.

The protagonist of the movie is university student Shiro Shimizu (Shigeru Amachi), a studious young man engaged to his professor's daughter, Yukiko (Utako Mitsuya). Shiro's life is full of temptation, some of which he's indulged in on his own (he and Yukiko have been sleeping together), and some of which he is egged into by his friend Tamura (Yoichi Numata). Tamura is a strange character, seemingly supernatural in his ability to appear out of nowhere and his limitless knowledge of other people's foibles. He knows about Shiro's sex life, and he not only knows about the war crimes of Yukio's father (Tarahiko Nakamura), he has photographic proof that shouldn't even exist. A devilish dandy who regularly arrives carrying a rose, Tamura has taken it upon himself to remind everyone that, even if he has no moral compass, the world does.

On a night out, Tamura and Shiro accidentally run down a drunken gangster (Hiroshi Izumida) in their car and leave him to die. Shiro is haunted by the deed, while Tamura is haunted by the fear that his weak-willed friend will rat them out. The gangster's mother (Kiyoko Tsuji) and girlfriend (Akiko Ono) swear revenge, but poetic justice catches Shiro first. A taxi ride with Yukiko ends with the car wrecked and the driver and Yukiko both dead--and just before Yukiko can confess to Shiro that she's pregnant. (Kind of a spoiler, I suppose, but I can't imagine anyone in the audience today not realizing what she's about to say when she is cut off.)

The two car crashes are the first of many doubles Nakagawa plays with in Jigoku, a reflection of the two plains of existence his story traverses, which is further reflected as the relationship between the audience and its cinema. The most significant of these pairs emerges when we are introduced to Sachiko, the girl Shiro meets when he returns home to visit his ailing mother (Kimie Tokudaji) and philanderer father (Hiroshi Hayashi). Sachiko, also played by Utako Mitsuya, is a doppelganger of Yukiko, which naturally does the boy's head in. He's also tempted by the dueling mistresses trying to lure him away from his heart's desire. Kinuko (Akiko Yamashita) has been bedding Shiro's father, but now she wants the son to take her to Tokyo, while Yoko, the former moll of the dead gangster, has come searching for Shiro at his hometown retreat. She carries a red umbrella, which contrasts to the pink umbrella used by both Yukiko and Sachiko--one is fiery and passionate, the other softer, more love than sex. (Yoko's lily is also a dark omen and contrasts with Tamura's rose.) Nakagawa even doubles-up on the cuckolding. Shiro's father is cheating with Kinuko as well as on her, but she is trying to cheat on him with his son, while it turns out that Shiro's mother was stolen by his father from the alcoholic painter Ensai (Jun Otomo), who is Sachiko's father. You almost need a flowchart to keep it all straight.

These sinners finally converge on a night of partying following the death of Shiro's mother. In another doubling, Shiro's father and the corrupt townspeople get drunk in one room while the residents of the old folks home he is caretaker for party in another. Both are inadvertently poisoned by two separate sources--the old people from the sustenance Shiro's father is meant to provide, the others as a result of their own debauchery and Shiro's sins. This massive group death thus pulls all of these souls down to Hell at the same time, where Nakagawa can visit their sins back upon them and we can finally start to get into the rancid meat of the movie.

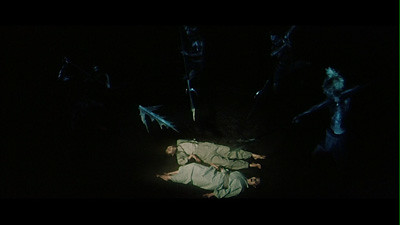

Hell in Jigoku is a nightmarish landscape, many of the special effects Nakagawa employs predicting the psychedelic aesthetic that would emerge later in the decade. At the start of the film, Yukiko's father is lecturing on the different versions of Hell that exist in the world's religions, but the focus is on the Buddhist variety and I would guess that Nakagawa draws a lot from that here. There is some fire and brimstone, but there is even more fetid water and obscuring smoke. It's like a dream that you can't get out of, where the farther you travel the less distance you actually traverse. There is nowhere to go, but the compulsion to find an escape is irresistible.

The various characters from the set-up are beset upon by demons and are delivered befitting punishments. The corrupt police officer (Hiroshi Shinguji) is placed in handcuffs so tight, they sever his hands at the wrist, while the one-eyed journalist (Koichi Miya), whose ocular infirmity was already a symbol of his inability to clearly see the truth, has his other eye gouged out. Tamura, who even in Hell is still picking at Shiro, is picked at himself, repeatedly stabbed by a demon's pitchfork. Immediately upon the completion of these tortures, the victims' bodies are restored (Kakagawa uses primitive jump cuts to go back and froth between each state) and it starts all over.

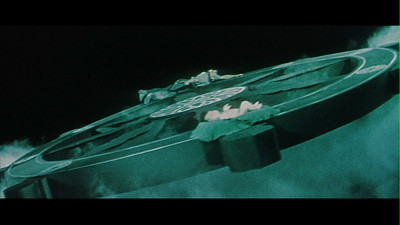

Nobuo Nakagawa really goes for it in these final scenes, and while the results aren't exactly terrifying, the inferno he creates is impressive in its ambition. In the earthly scenes, the director had already employed extreme angles--shooting from below and above and from voyeuristic vantage points; inverting the image at morally crucial moments to suggest that any sense of up or down, right or wrong, has been lost--but he takes it to the extreme once he takes us to the underworld. Anything goes at this point. There are distorted colors, irises that warp the pictures like funhouse mirrors, burning lakes of blood and boiling cauldrons, a swinging pendulum blade, mountainous eruptions, spinning wheels, throngs of sinners driven mad with panic, demons with bows and arrows--if the filmmakers could think of it, they put it in the movie.

There is also a journey waiting to be completed. Shiro has a last chance to save himself, and in so doing preserve the innocent. The good women of his life--his mother and his two love interests--are both on hand to encourage and cajole, and they being the only ones not being tortured suggests that they are not meant to be there, and perhaps Shiro completing his goal will save them as well. His quest requires him to traverse the pitfalls of Hell, often walking against the tide of sinners, following the sound of the crying baby in order to rescue the child from being lost to evil. This baby is actually his and Yukiko's unborn child.

It all gets pretty freaky, and there is enough blood in this cinematic damnation to make up for the bloodless set-up. Though the special effects are clumsily theatrical by today's standards, the rawness of the expression actually invokes the primal source from which the frights emerge. Thankfully, even with the religion at the base of this picture, Nobuo Nakagawa also manages to keep Jigoku from being at all moralistic, allowing us to just enjoy his lurid imagination without having to take a lesson away from it. Actually, if one wanted to, the ambiguousness of the final shots could even be argued to reinforce a notion that all of this is meaningless and there is nothing beyond the life we live on this plain. Shiro caught in a circular struggle cuts us off before the predictable narrative closure can be achieved, and the camera returning to the lifeless bodies at the scene of the death, drifting over to the painter and the portrait of Hell he had been working on, reminds us that this is just a vision and nothing more. It's as if seeing Ensai's nightmarish creation inspired nightmares in those who have just passed into eternity's dreaming, but in the waking world, they remain exactly where they fell.

Friday, October 10, 2008

MONSTERS & MADMEN (#364): CORRIDORS OF BLOOD - #368

The second Boris Karloff movie in the Monsters & Madmen boxed set is not the expected monster flick, but instead a melodrama with tinges of Victorian horror and elements of morbid tragedy. 1959's provocatively titled Corridors of Blood is the story of Dr. Thomas Bolton, a surgeon in 1840s London obsessed with the idea of finding a way to perform operations without causing the patients great pain. No anesthetics had yet been invented, and so swiftness is believed to be the best way to operate with a minimum of harm. Bolton is the speediest cutter in the hospital, but the screams of those he means to help still haunt him.

In addition to his duties at the hospital, Bolton is a humanitarian who spends his off hours providing free medical care to the poor in the Seven Dials slum, and in a movie like this, it's a fair bet that anyone this good is likely to be taken advantage of. Bolton is preyed upon by unsavory types; in particular, Black Ben (Francis De Wolff), the owner of a seedy tavern in the ghetto. Ben tricks the good doctor into signing a death certificate for a cadaver he swears died of a fever but who was really strangled by Ben's colleague, the sinister Resurrection Joe (Christopher Lee). With proof of a legal death in hand, they can sell the body to Bolton's hospital to be chopped up by eager students.

An accident with his own laughing gas concoction leaves a giggling Dr. Bolton wounded from broken glass but surprisingly free of pain. His niece, Susan (Bella St. John), points out that he must have found the formula he has been looking for if he didn't feel the cut, and so Bolton amps up his efforts. Determined to find the right combination of chemicals, he continues experimenting on himself. Huffing his dangerous gas, he goes into fevered states, wandering to Black Ben's in the middle of the night and completely forgetting everything by morning. The more he experiments, the worse it gets. His surgery begins to suffer, and he even takes a hit to perk himself up so he can face company Susan has invited over to the house. Dr. Bolton has become a full-blown addict! Suspended from work, he starts suffering withdrawals, and he makes a pact with Ben and Joe to trade more death certificates for helping him steal the chemicals he needs for his drug. Murder follows, and the doctor makes his final descent into the darkness.

Every time Karloff would hook himself up to his gas contraption, a kind of mad scientist hookah, I kept expecting him to turn into a deformed killer like the one he played the year before, working with the same director (Robert Day) and producer (Richard Gordon), in The Haunted Strangler. No such luck. Anyone looking for more shocking thrills and chills are likely to be disappointed by Corridors of Blood. Most of that blood is confined to the hospital and the gruesome surgeries Bolton performs, and the closest we get to a monster is the menacing Resurrection Joe. Christopher Lee makes an imposing villain. Tall and thin, dressed in a long black coat and a stove pipe hat, his angular face cut by shadows and marked by scars, Joe says little but he does much. The most horrific act of violence in the movie isn't when he snuffs out the life of his victims with a filthy pillow, but when he sexually assaults the flirty waitress Rosa (Yvonne Warren), smiling at her cries of terror.

Too bad there isn't more of Resurrection Joe. I wouldn't have minded if he had been the doc's sidekick rather than Black Ben's, bringing him live test subjects to try his creations on. Unfortunately, without either of these men unleashing their darker talents, Corridors of Blood can be a little slow going. Robert Day shoots the picture in a rather straight-ahead style, relying on Karloff's panic to convey the frenzied emotions when sharper angles and exaggerated focus could have really amped up the paranoia. Even the doctor's hallucinations are rather staid, getting no crazier than simple double vision.

Perhaps it's a case of misguided expectations, I was too busy looking for what I thought would be there to see what really was, but in a boxed set called Monsters and Madmen I expect one or the other in the movies contained therein. Corridors of Blood had the potential to have both, and they could have even done it without resorting to the supernatural. (Though, why shouldn't they? It's not like Thomas Bolton was real!) A more wicked Resurrection Joe, a less scrupulous and more driven doctor--these things could have meant we'd really see some bloodstained hallways. Instead, we're safely shielded from the splatter. Dr. Thomas Bolton wanted painless surgery, and instead he got a painless movie.

Sunday, October 5, 2008

LE DEUXIEME SOUFFLE - #448

The title of Jean-Pierre Melville's 1966 crime picture Le deuxiéme souffle translates as "second wind," and that seems as much of a description for the director as it is for his main character, the aging hoodlum Gu (Lino Ventura). Not that Melville had run out of steam, but there is a marked difference between a more conventional hardboiled tale like 1962's Le doulos and 1967's philosophical hitman picture Le samourai. If the former is point A and the latter point C, then Le deuxiéme souffle is point B.

Gu (short for Gustave) has served ten years of a life sentence for robbing a train full of gold when he and two other prisoners stage a prison break. Working quietly in the late night and performing dangerous acrobatics that leave one of them dead, the men forge ahead with a steely professionalism that Melville gives to all of his best criminal characters. It's the mood that will dominate Le deuxiéme souffle, and it will carry through Melville's final spate of movies, all the way to Un flic in 1972.

A lot has happened in Paris since Gu got pinched. The Ricci family dominates the underworld, with the more respectable brother, Paul (Raymond Pellegrin), running things in Marseille and the sleazier Jo (Marcel Bozzufi) holding court from his bar in Paris. There is some clash between the two cities, and Paul has had some problems with a shady crook who stiffed him on a cigarette deal. Hitmen on the Ricci payroll take him out at a rival restaurant run by Manouche (Christine Fabréga), a classy dame who also happens to be Gu's sister. Her barman and bodyguard, Alban (Michel Constantin), is one of Gu's old partners, as well, and the escaped convict just so happens to drop in just in time to save both of their bacons from some blackmail artists Jo sent their way post-assassination. It's just that kind of reliable behavior that, alongside having never sold out his accomplices, has earned Gu a lot of friends over the years. There is honor among thieves, and Gu is respected enough that even if another bad guy sees him, no one is going to squeal.

On the flipside is Inspector Blot (Paul Meurisse), the leading police detective in Paris, a man who has seen it all and knows all the angles even before the crooks can have a chance to run them. His name is pronounced with a soft "T" in French, but the American pronunciation fits him: if Blot sets his sights on you, his gaze blocks out all else.

Like the crooks, Blot operates along a certain line. There are things he will do, and things he will not. The law is flexible, and he can respect those who work within the lines, but these days, the standards of conduct are constantly shifting. Gu, for instance, doesn't understand how Blot can be friendly with someone like Jo Ricci. In his day, the criminals kept to their side of things, and police kept to the other. There is a new generation that does not see it in the same either/or manner, however. The trigger happy Antoine (Denis Manuel), on one hand, doesn't put a lot of stock in a man's word as his most sacred weapon; on the other hand, Inspector Fardiano (Paul Frankeur) doesn't shy away from resorting to police brutality to get a confession.

Le deuxiéme souffle is a methodical step-by-step of Gu's flight for freedom. Over the course of a month--Melville constantly reminds us of the date, like a calendar of doom ticking off the days (more on that later)--Gu moves from Paris to Marseille, gets connected to a big platinum score, and plots his getaway out of France and home to Italy. The thief is trying to gain his second wind, to start the second act of his life after a decade-long intermission. All the while Blot keeps his feelers out for the fugitive, waiting for him to trip up. Likewise, old rivalries come to bear and older friendships are tested.

Le deuxiéme souffle was adapted by Melville from the book and screenplay by José Giovanni, the real-life criminal who also wrote Classe tous risques and the jailbreak picture Le trou, the latter based on his own famous prison escape. Giovanni rarely resorts to gangster movie clichés, instead writing his scripts more like reportage. To match this, Melville and cameraman Marcel Combes shoot Le deuxiéme souffle in a pseudo-documentary style, almost like French Noir Neorealism. They use real locations and a loose, fluid camera style that follows the action rather than dictating where the action goes, maintaining a spontaneity even in the carefully planned crime sequences or Gu's overly cautions travel patterns. The platinum hijacking is shot as a virtuoso action scene, each moment planned to the tiniest detail, and with the patience and precision of the jewelry store break-in in Dassin's Rififi (later aped by Melville in Le cercle rouge). The men don't speak, they just fulfill their roles. Yet, even with this eye towards realism, the director doesn't abandon the expressive shadows of old-school noir completely. Take, for instance, when Manouche goes to see Blot, and the police station corridor is so dark, we can barely see their faces. It's questionable whether Manouche is being led to her salvation or destruction.

Giovanni's felons are only glamorous in the sense that they come off as lone warriors trying to stave off change, to continue to operate within a system that is becoming obsolete. Lino Ventura played a similar criminal type in Classe tous risques, the older thief who is ready to get out of the game. Melville likely saw something in these men that appealed to him. His crooks are professionals who do their jobs and they do them well, or else they might lose their lives, much in the same way hardboiled gumshoes of American detective fiction managed to maintain a level of good in a rotten world by sticking to their manly code of personal ethics and the structure of "how things are done." The ultimate expression of this ideal would come a year later, realized by Alain Delon in Le samourai, but Le deuxiéme souffle has a trench-coated precursor to Delon's hitman in Orloff (Pierre Zimmer), the movie's ultimate get-it-done man. He's the one who hooks Gu up with the platinum heist, forgoing the big money himself, all because he respects Gu and knows he needs the work. Orloff doesn't even want credit for it, forbidding anyone to tell Gu he was responsible even while vouching for the older hood's viability. Orloff says Gu can do it, and that should be good enough; likewise, when things do go wrong, there is nothing more important to Gu than clearing his name.

And trust me, it's not a spoiler to reveal that things go wrong. From the very start of Le deuxiéme souffle, there is a sense of impending doom hanging over Gu. It's not just that calendar, either, though that does serve as reminder of time running out--not that we know when the deadline is, just that one is coming. Before Gu even appears on screen, a title card informs us that some believe that man's only true power in life is to choose the time of his own death, though for any one of us to give up simply because we are tired is to waste everything we have experienced prior. Once we read that, we know that Gu can only have one destination, it's just a question of how he gets there. In one sense, I suppose, we know he can never escape and just retire, that wouldn't fit Melville's mission statement. We also can't believe someone as meticulous as Gu would walk into his own death without at least having some plan for escape. No, Melville never intended his little lead-in to be taken so literally.

Rather, the director was giving us something to chew on, like the Eastern proverbs he would use in Le samourai and Le cercle rouge, little pearls of wisdom for the audience to roll around in their heads while watching the drama unfold. As our existential hero, Gu isn't looking to end his life, but instead he attempting to take back his right to choose his own fate, to wrest it away from the cops and criminals who are trying to dictate how he will go out. This solidifies metaphorically as his eventual quest to clear his name, to prove to his peers that he is not a rat. The one time he actually does attempt suicide, it's a desperate, flailing attempt to silence the lies. In a hard-bitten society like this one, actions must trump words. Honor matters, but it's what a man does that proves he has it.

Inadvertently, Gu's actions offer Blot a chance at redemption, too. The detective, portrayed with smug calculation by Meurisse, has gone too far in stirring the pot, resorted to too many tricks, and allowed a less talented police officer to ruin the case he has made through unseemly tactics. In his final action in the film, Blot moves to put things right by finishing what Gu started.

As the credits roll, Le deuxiéme souffle leaves one with the strange satisfaction of a self-fulfilling prophecy. While in other instances, Gu's fate would be cause for sadness, in this case, it comes off more as a job completed. It still gives us reason to reflect, but not to lament.

Friday, October 3, 2008

MONSTERS & MADMEN (#364): THE HAUNTED STRANGLER - #367

In England in 1860, a one-armed man is hung as the Haymarket Strangler; twenty years later, a crusading novelist researching the case discovers that the dead man was not the guilty party after all--a theory proven when the killer returns!

Boris Karloff stars in The Haunted Strangler as James Rankin, a writer with an interest in curing society's ills. He intends to use his latest effort to prove that due to the fact that the impoverished can't afford proper legal aid, innocent men are often condemned. Doing just a little detective work with his assistant, Dr. McColl (Tim Turner), Rankin begins to create an alternate theory regarding the young doctor who both performed the autopsies on all of the murdered women and can be placed at the scene when the hanged man was identified. The Haymarket Strangler's modus operandi was to choke his female victims with one hand, and when that had done as much damage as it could, he would slice them up with a knife. Thus, when a dancing girl, Cora (Jean Kent), saw a one-armed man fleeing after murdering one of her co-workers, the case was apparently cracked.

Except that there could have been other explanations for the killer only using one arm, and new clues lead Rankin to believe that the key to the case is the missing knife used by the killer. Find it, and maybe then the connection to the missing doctor will follow. Believing that the instrument of death was stashed with the corpse of the wrongfully accused, Rankin digs up the casket. Inside, amongst the dirt and bones, he finds what he seeks, but he also gets more than he bargained for. With the surgical scalpel in hand, Rankin is transformed into the Haymarket Strangler!

The Haunted Strangler (known as Grip of the Strangler in the UK) was the inaugural production effort of Richard Gordon, whose film background had included publicity and distribution before Boris Karloff convinced him to put up the cash for a story writer Jan Read had put together for the legendary horror actor. Made simultaneously with the sci-fi shocker Fiend Without a Face, Gordon dialed into the exploitation formula from the get-go. Though The Haunted Strangler makes pretenses of being about greater social issues, it's the luridness of the plot and the setting that dominates. Karloff's Rankin may be interested in correcting injustices, and the subtext in regards to whom the victims are, both the hanged man and the strangler's women, is that there is a segment of society that exists beyond the benefit of law and order. All such concerns are quickly set aside, however, making way for the brutal descriptions of the sexually motivated slayings and the scuffles between the possessed writer and police. Shots of whipped prisoners with bloody lashes across their backs or Karloff slicing up a guard's face with broken glass are pretty graphic for 1958, as is the twisted psychology that motivates the murders. Multiple scenes of cancan girls and a champagne spilled down Vera Day's cleavage also add to the idea that The Haunted Strangler wasn't really a high-falutin' social drama. Screams and titillation are the order of the day!

Are these shots just for cheap gawking, or are they foreshadowing of the defilement to come? Pretty soon, that pretty neck will be wrung and that porcelain skin will be stained with blood.

The picture was designed specifically for Karloff, and it's very much his vehicle. His transformation from moralistic novelist to psycho killer is done without the benefit of make-up or prosthetics. Karloff's only special effect is his body. He gnarls his hand into a claw and contorts his face so that one side looks like it's stuck in a permanent flinch, like he was punched and never recovered. Though it looks slightly comical by today's standards, Karloff gives 100% of himself to the performance. There seems to be added psychology in the fact that the malformed arm and the pinched half of his face are on two different sides of his body. He's no mere Jekyll and Hyde split in twain, but a far more twisted creature.

The story here, complete with the scenes of grave robbing and mental asylums, reminds me of two pictures Karloff made under the aegis of producer Val Lewton a decade prior: The Body Snatcher

The Haunted Strangler is part of the four-movie Monsters and Madmen boxed set, and I'd be remiss if I didn't note that the cover artwork was created by popular comic book artist Darwyn Cooke, creator of DC: The New Frontier

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)