If you're looking for something to do this Thursday, come out and see the gallery show featuring artwork for my next book with Joëlle Jones, You Have Killed Me. Details here.

IN THEATRES...

* 12, a truly awful Russian remake of 12 Angry Men.

* The Brothers Bloom, the second film from Brick's Rian Johnson is the movie to see this weekend. The trailer only touches on it, it doesn't do it justice. With Mark Ruffalo, Adrien Brody, Rachel Weisz, and Rinko Kikuchi.

* Rudo y Cursi, a cute sports movie reuniting the stars of Y tu mama tambien.

* Star Trek--holy crap, this was really good! And I don't even like Star Trek! Who'd have thunk?!

* Terminator Salvation, a total letdown. The franchise is dead. But you're going to go see it anyway, so if nothing else, heed my advice and bring a neck pillow, because you're going to want to take a nap.

* Up! Oh, Pixar, how do you keep doing it? I love you so.

And don't forget Revanche, which has been playing in New York and has already been reviewed on this site.

ON DVD...

* 3 Seconds Before Explosion, a fun but formulaic 1960s crime movie from Japan that doesn't quite live up to the promise of its name.

* Alexandra, a hypnotizing portrait of the state of things by Alexander Sokurov.

* El Dorado - The Centennial Collection, a fun latter-day western from Howard Hawks, starring John Wayne, Robert Mitchum, and James Caan.

* Enchanted April, an old Merchant Ivory wannabe. The magic is gone.

* Girl on a Motorcycle, wherein the 1960s drives up its own ass, taking Marianne Faithfull and Alain Delon with it.

* Just Another Love Story, an uneven crime film from Denmark.

* Man Hunt, Fritz Lang's 1941 thriller about a man who would've killed Hitler, but found himself on the run instead.

* Two 1980s films from Alain Resnais: Mélo, an emotionally powerful drama of infidelity, and Love Unto Death, which turns out to be overly intellectual and kind of dull.

* Revolutionary Road, Sam Mendes' literary adaptation with Leonardo DiCaprio and the divine Kate Winslet is one of my favorite films from 2008.

* Wendy and Lucy, a quiet portrait of solitude and struggle with a stand-out performance from Michelle Williams.

Sunday, May 31, 2009

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

WISE BLOOD - #470

"Where you come from is gone, where you thought you were going to weren't never there, and where you are ain't no good unless you can get away from it."

We all have "ah-ha" moments in life, some important, some trivial. In terms of the trivial, one of mine was the first time I watched Wise Blood and realized at long last where the sample of the above quote used in Ministry's industrial psychobilly rave-up "Jesus Built My Hotrod " came from. My life wasn't changed or anything, but as someone who appreciates how one piece of art feeds into another, how influences get passed around like a "take a penny, leave a penny" jar, it was a pretty cool factoid to stumble across. Once the piece is in place, Ministry's obsession with Southern white trash culture suddenly makes a little more sense. Even the "industrial" tag takes on a whole new meaning: music born out of the factories and the auto plants, sounding a little like Hazel Motes' sputtering automobile set to a heavy beat.

" came from. My life wasn't changed or anything, but as someone who appreciates how one piece of art feeds into another, how influences get passed around like a "take a penny, leave a penny" jar, it was a pretty cool factoid to stumble across. Once the piece is in place, Ministry's obsession with Southern white trash culture suddenly makes a little more sense. Even the "industrial" tag takes on a whole new meaning: music born out of the factories and the auto plants, sounding a little like Hazel Motes' sputtering automobile set to a heavy beat.

John Huston's 1979 adaptation of the Flannery O'Connor novel is itself a weird amalgamation of various traditions of cinematic comedy, rural music, and religious hucksterism. It takes a soul possessed of a particular black humor to properly translate O'Connor, and Huston's directorial career is full of examples of his like-minded distrust of authority and his somewhat cynical view of the human condition. Consider the religious piety he dismantles with The African Queen

is itself a weird amalgamation of various traditions of cinematic comedy, rural music, and religious hucksterism. It takes a soul possessed of a particular black humor to properly translate O'Connor, and Huston's directorial career is full of examples of his like-minded distrust of authority and his somewhat cynical view of the human condition. Consider the religious piety he dismantles with The African Queen , or the endings of The Maltese Falcon or The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

, or the endings of The Maltese Falcon or The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and what they have to say about objects of man's worship. Or look at Huston the actor at the close of Chinatown

and what they have to say about objects of man's worship. Or look at Huston the actor at the close of Chinatown for the ultimate in taboo revelations.

for the ultimate in taboo revelations.

O'Connor's Wise Blood pulls a dual trick: it is on one hand a scathing portrayal of how modern religion is distorted and how the hungry lambs of Christ are eager to gobble it up and be fooled, and on the other hand, it is a sympathetic portrait of a true believer, however misguided he may be. Hazel Motes is an odd and complex character, full of contradictions, walking and talking his internal conflict like it's the only thing he has in the world. The casting of Brad Dourif as the would-be street corner preacher was a perfect coupling of actor and role. It's one of those performances where, once you see it, it's impossible to imagine anyone else playing the part or even to see Dourif doing anything else. For as great as he was in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and, more recently, Deadwood

and, more recently, Deadwood , to me, he'll always be Hazel Motes.

, to me, he'll always be Hazel Motes.

Wise Blood was published in 1952, and it portrayed a post-War American South that the industrial age has all but abandoned. Huston updates the story in so much as he doesn't really set it in any specific timeframe. Cars, clothes, and locations bear some resemblance to the late '70s, but the true setting is one of those unchanging out of the way 'burgs one can find all across the U.S. They are of every age and of none.

Hazel returns to the area of his birth following a stint in the army. He is eager to discard his uniform and his service, only willing to note that he was discharged due to injury but unwilling to disclose how he was injured, implying that it was in a place too embarrassing to mention. Whatever it was, it has forever changed him, and he's eager to move on, buying a new suit and heading for a new town, loudly proclaiming that he wants to experience new things he's never experienced before. It's almost like advertising copy. "New! New! New!" In contrast, there are billboards and marquees all over the place declaring the old gospel, the message of Protestant morality that is being pushed at Hazel and the one he wants to reject.

Once Hazel gets to where he's going, a strange group of characters starts to congregate around him. If he is the new Messiah, these are his mental ward disciples. One man becomes his sort of nemesis, the blind street preacher Asa Hawks (Harry Dean Stanton). Though obviously a charlatan, Hawks picks up on the signs that Hazel has a dark past that has made him angry with religion. We see some of this as flashbacks, with the director Huston appearing as Hazel's grandfather, a fire-and-brimstone preacher who peddled his wares in revival tents when Hazel was just a boy. Hawks declares that Hazel is either marked to be a preacher or some other preacher has placed his mark on him, and he insists Hazel is drawn to him to put things right. It's a father/son scenario in its way, with Hazel's rebellion being like the angry teenager who wants to rebuke his own heritage.

There is something amusingly adolescent about all of Hazel's rejections. His constant insistence that he believes in nothing reminding me both of earnest punk rock sloganeering and the hilarious nihilists from The Big Lebowski. Hazel decides to give Hawks a run for his money, and he sets up his own church, The Church of Truth without Christ, a new denomination of Christianity where there is no Jesus, no sin, no forgiveness. There is only each and every man, the savior of himself.

Keep in mind that all of this is presented with the blackest of tongues pressed firmly into the darkest of cheeks. While Hazel treats his mission with deadly seriousness, Huston does anything but. One of the main things that the director, along with screenwriters Benedict and Michael Fitzgerald, draws from O'Connor is that much of modern religion is a side show. The better your pitch, the more freakish your display, the more likely you are to get an audience. Hence, Hawks having blinded himself with quick lime to prove his belief. In the flashbacks, we also see that Hazel's grandfather set up shop with traveling carnivals, and Hazel snuck over from the preaching tent to see the naked woman in a coffin in one of the neighboring tents (thus, sex and death and a repentant soul are all linked in the boy). Likewise, we get the modern church of the motion picture, and the bizarre spectacle of Gonga, Monarch of the Jungle. Merely a man in an ape suit, he suffers the little children unto his church so they can bear witness to his onscreen pilgrimage, apparently emerging from the wicked wilderness to sell tickets.

Gonga in the film version of Wise Blood is both one of the film's most potent symbols as well as part of one of its most pronounced foibles. The movie ape is part of a side story with Hazel's most fervent follower, the dumb-as-wood Enoch Emory (Dan Shor). Another country boy adrift in the city, Enoch is desperate enough for friends to keep chasing Hazel around despite the angry man's constant abuse. In one of the funniest scenes in the movie, Enoch stands in front of the monkey cage at the zoo where he works hurling insults at the monkeys. Shor's posture is deliberately chimp-like, and it's ironic that he will eventually embrace what he hates. After he sees how easily Gonga makes friends, the boy steals the gorilla suit and runs around town trying to shake people's hands, finding connection at last.

Unfortunately, much of the comedy in the Enoch scenes is too broad. The lowest point is when he dons a wig and prop moustache to steal a shrunken man from the museum, believing the relic of a savage land to be the perfect idol for Hazel's church. I assume Huston is intentionally emphasizing the silliness of the scene, playing up Enoch's place in the story as the idiot seer (he's the one with "wise blood," a self-proclaimed ability to read signs and symbols). Huston stages his activities like segments of a Keystone Cops film, but these scenes end up looking clumsy and amateurish. They are incongruous to the heavier satire of the main plot. This isn't helped by Alex North's score, which is largely variations on the song "Tennessee Waltz," played on everything from a banjo to modern synthesizers. It's a fine idea, fitting some of the ideas the film wishes to illustrate in terms of how modernity and tradition are clashing, but like so many of the more technologically "progressive" movie soundtracks of the late '70s and early '80s, it ends up being the one thing that really dates Wise Blood.

Hazel Motes is definitely a man out of time, though. He is neither part of the old Southern tradition, nor does he fit in the new world. His is the plight of the existential philosopher in a world sticking to medieval mythology. Again, it's that idea of modernity versus tradition. What's the new God in a technological world? Why, a fine automobile, of course! Hazel sees his car as his mode of delivery, the chariot that will take him away from his earthly problems; the rest of the world looks at his car and sees it is breaking down, but he insists he will keep in running, it will get him where he needs to go. He doesn't care if he is trading one junk heap of belief for another, religion makes all men blind if they so desire--and in some cases in this story, literally.

In fact, both O'Connor and Huston want to show how easy it is to replace a prophet, be it Enoch's false idol or Hazel replacing Asa Hawks, and then Hazel being replaced in turn. One of the best sequences in Wise Blood comes when Ned Beatty shows up as Hoover Shoates, another religious con man who spots a good partner in Hazel. When Hazel refuses to go along and let his Church of Truth without Christ be co-opted, Hoover gets another man (William Hickey) with his own car to dress up like Hazel and be his prophet for the slightly altered, contradictory Church of Christ without Christ. Add an acoustic guitar, and they've got a better show than their inspiration, and Hazel is practically out of business.

The ironic problem with Hazel is that for all the bunk he is peddling, he is the only true honest man in all of Wise Blood. He actually believes his own b.s. This adds a level of tragedy to his comic downfall, and it's something that Dourif is particularly skilled at portraying. The actor uses his skinny, almost frail body and juxtaposes it with an intense manner. Hazel is an angry character, unyielding in his conviction. As a result, he often misses the human connections offered to him, be it Enoch's friendship or the landlady (Mary Nell Santacroce) who wants to take care of him at the end of the movie. His only real relationships, surprisingly enough, are sexual ones, first with the prostitute he goes to when he first gets to town and then with Hawks' maybe-daughter, Sabbath Lily (Amy Wright).

Sabbath Lily is arguably Hazel's Eve, though her seduction in the garden ends up being her failed come-on in a grotty forest. Their coupling adds to the element of tragedy, though it is more Greek than it is Christian. When Hazel takes the girl from her father, who is also his surrogate father, the outcome is both inevitable and Oedipal. Hazel's old-world penance is right out of Sophocles.

It can be hard sometimes to know for sure whether certain style decisions are intentional or whether or not they are just how things turned out. In this case, I don't know if the low-rent look of Wise Blood was deliberate on John Huston's part (the man did allow his name to be misspelled in the hand-scrawled credits) or if it was just a matter of budget, but either way, the film's rundown appearance perfectly fits the setting. As I noted, the towns Hazel visits have been all but abandoned by the rest of the country. They are as behind the times in their appearance and conveniences as they are in their ideas (many of the characters, including Hazel, make no secret of their racism). Much of the film takes place outdoors, but there is a perpetual gray pallor over everything, like the skies are permanently overcast. The new Criterion DVD is light years better than any of the old VHS copies I had seen prior, showing every crack, every faded patch of paint. These folks may be stuck where they are, unable to move forward, but they aren't immune to decay.

That timelessness ultimately works in favor of Wise Blood, which is one of the stranger films of John Huston's extensive career, to be sure. As I said, the only real failings come when he attempts to contemporize things. If only folks back then knew that synthesizer music came with an expiration date, they would have likely avoided it. Sometimes I feel like a broken record (there's a dated reference!) in pointing out how old films have a poignancy to our current political situations, but Wise Blood strikes as close to home now as it likely did when O'Connor first wrote her novel. Returning vets, economic hardships, overzealous religious zealots competing for who has the bigger belief--seriously, how is it that we never learn? Hazel Motes tried to teach us, but we wouldn't listen. Does that mean his failure is our own?

We all have "ah-ha" moments in life, some important, some trivial. In terms of the trivial, one of mine was the first time I watched Wise Blood and realized at long last where the sample of the above quote used in Ministry's industrial psychobilly rave-up "Jesus Built My Hotrod

John Huston's 1979 adaptation of the Flannery O'Connor novel

O'Connor's Wise Blood pulls a dual trick: it is on one hand a scathing portrayal of how modern religion is distorted and how the hungry lambs of Christ are eager to gobble it up and be fooled, and on the other hand, it is a sympathetic portrait of a true believer, however misguided he may be. Hazel Motes is an odd and complex character, full of contradictions, walking and talking his internal conflict like it's the only thing he has in the world. The casting of Brad Dourif as the would-be street corner preacher was a perfect coupling of actor and role. It's one of those performances where, once you see it, it's impossible to imagine anyone else playing the part or even to see Dourif doing anything else. For as great as he was in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

Wise Blood was published in 1952, and it portrayed a post-War American South that the industrial age has all but abandoned. Huston updates the story in so much as he doesn't really set it in any specific timeframe. Cars, clothes, and locations bear some resemblance to the late '70s, but the true setting is one of those unchanging out of the way 'burgs one can find all across the U.S. They are of every age and of none.

Hazel returns to the area of his birth following a stint in the army. He is eager to discard his uniform and his service, only willing to note that he was discharged due to injury but unwilling to disclose how he was injured, implying that it was in a place too embarrassing to mention. Whatever it was, it has forever changed him, and he's eager to move on, buying a new suit and heading for a new town, loudly proclaiming that he wants to experience new things he's never experienced before. It's almost like advertising copy. "New! New! New!" In contrast, there are billboards and marquees all over the place declaring the old gospel, the message of Protestant morality that is being pushed at Hazel and the one he wants to reject.

Once Hazel gets to where he's going, a strange group of characters starts to congregate around him. If he is the new Messiah, these are his mental ward disciples. One man becomes his sort of nemesis, the blind street preacher Asa Hawks (Harry Dean Stanton). Though obviously a charlatan, Hawks picks up on the signs that Hazel has a dark past that has made him angry with religion. We see some of this as flashbacks, with the director Huston appearing as Hazel's grandfather, a fire-and-brimstone preacher who peddled his wares in revival tents when Hazel was just a boy. Hawks declares that Hazel is either marked to be a preacher or some other preacher has placed his mark on him, and he insists Hazel is drawn to him to put things right. It's a father/son scenario in its way, with Hazel's rebellion being like the angry teenager who wants to rebuke his own heritage.

There is something amusingly adolescent about all of Hazel's rejections. His constant insistence that he believes in nothing reminding me both of earnest punk rock sloganeering and the hilarious nihilists from The Big Lebowski. Hazel decides to give Hawks a run for his money, and he sets up his own church, The Church of Truth without Christ, a new denomination of Christianity where there is no Jesus, no sin, no forgiveness. There is only each and every man, the savior of himself.

Keep in mind that all of this is presented with the blackest of tongues pressed firmly into the darkest of cheeks. While Hazel treats his mission with deadly seriousness, Huston does anything but. One of the main things that the director, along with screenwriters Benedict and Michael Fitzgerald, draws from O'Connor is that much of modern religion is a side show. The better your pitch, the more freakish your display, the more likely you are to get an audience. Hence, Hawks having blinded himself with quick lime to prove his belief. In the flashbacks, we also see that Hazel's grandfather set up shop with traveling carnivals, and Hazel snuck over from the preaching tent to see the naked woman in a coffin in one of the neighboring tents (thus, sex and death and a repentant soul are all linked in the boy). Likewise, we get the modern church of the motion picture, and the bizarre spectacle of Gonga, Monarch of the Jungle. Merely a man in an ape suit, he suffers the little children unto his church so they can bear witness to his onscreen pilgrimage, apparently emerging from the wicked wilderness to sell tickets.

Gonga in the film version of Wise Blood is both one of the film's most potent symbols as well as part of one of its most pronounced foibles. The movie ape is part of a side story with Hazel's most fervent follower, the dumb-as-wood Enoch Emory (Dan Shor). Another country boy adrift in the city, Enoch is desperate enough for friends to keep chasing Hazel around despite the angry man's constant abuse. In one of the funniest scenes in the movie, Enoch stands in front of the monkey cage at the zoo where he works hurling insults at the monkeys. Shor's posture is deliberately chimp-like, and it's ironic that he will eventually embrace what he hates. After he sees how easily Gonga makes friends, the boy steals the gorilla suit and runs around town trying to shake people's hands, finding connection at last.

Unfortunately, much of the comedy in the Enoch scenes is too broad. The lowest point is when he dons a wig and prop moustache to steal a shrunken man from the museum, believing the relic of a savage land to be the perfect idol for Hazel's church. I assume Huston is intentionally emphasizing the silliness of the scene, playing up Enoch's place in the story as the idiot seer (he's the one with "wise blood," a self-proclaimed ability to read signs and symbols). Huston stages his activities like segments of a Keystone Cops film, but these scenes end up looking clumsy and amateurish. They are incongruous to the heavier satire of the main plot. This isn't helped by Alex North's score, which is largely variations on the song "Tennessee Waltz," played on everything from a banjo to modern synthesizers. It's a fine idea, fitting some of the ideas the film wishes to illustrate in terms of how modernity and tradition are clashing, but like so many of the more technologically "progressive" movie soundtracks of the late '70s and early '80s, it ends up being the one thing that really dates Wise Blood.

Hazel Motes is definitely a man out of time, though. He is neither part of the old Southern tradition, nor does he fit in the new world. His is the plight of the existential philosopher in a world sticking to medieval mythology. Again, it's that idea of modernity versus tradition. What's the new God in a technological world? Why, a fine automobile, of course! Hazel sees his car as his mode of delivery, the chariot that will take him away from his earthly problems; the rest of the world looks at his car and sees it is breaking down, but he insists he will keep in running, it will get him where he needs to go. He doesn't care if he is trading one junk heap of belief for another, religion makes all men blind if they so desire--and in some cases in this story, literally.

In fact, both O'Connor and Huston want to show how easy it is to replace a prophet, be it Enoch's false idol or Hazel replacing Asa Hawks, and then Hazel being replaced in turn. One of the best sequences in Wise Blood comes when Ned Beatty shows up as Hoover Shoates, another religious con man who spots a good partner in Hazel. When Hazel refuses to go along and let his Church of Truth without Christ be co-opted, Hoover gets another man (William Hickey) with his own car to dress up like Hazel and be his prophet for the slightly altered, contradictory Church of Christ without Christ. Add an acoustic guitar, and they've got a better show than their inspiration, and Hazel is practically out of business.

The ironic problem with Hazel is that for all the bunk he is peddling, he is the only true honest man in all of Wise Blood. He actually believes his own b.s. This adds a level of tragedy to his comic downfall, and it's something that Dourif is particularly skilled at portraying. The actor uses his skinny, almost frail body and juxtaposes it with an intense manner. Hazel is an angry character, unyielding in his conviction. As a result, he often misses the human connections offered to him, be it Enoch's friendship or the landlady (Mary Nell Santacroce) who wants to take care of him at the end of the movie. His only real relationships, surprisingly enough, are sexual ones, first with the prostitute he goes to when he first gets to town and then with Hawks' maybe-daughter, Sabbath Lily (Amy Wright).

Sabbath Lily is arguably Hazel's Eve, though her seduction in the garden ends up being her failed come-on in a grotty forest. Their coupling adds to the element of tragedy, though it is more Greek than it is Christian. When Hazel takes the girl from her father, who is also his surrogate father, the outcome is both inevitable and Oedipal. Hazel's old-world penance is right out of Sophocles.

It can be hard sometimes to know for sure whether certain style decisions are intentional or whether or not they are just how things turned out. In this case, I don't know if the low-rent look of Wise Blood was deliberate on John Huston's part (the man did allow his name to be misspelled in the hand-scrawled credits) or if it was just a matter of budget, but either way, the film's rundown appearance perfectly fits the setting. As I noted, the towns Hazel visits have been all but abandoned by the rest of the country. They are as behind the times in their appearance and conveniences as they are in their ideas (many of the characters, including Hazel, make no secret of their racism). Much of the film takes place outdoors, but there is a perpetual gray pallor over everything, like the skies are permanently overcast. The new Criterion DVD is light years better than any of the old VHS copies I had seen prior, showing every crack, every faded patch of paint. These folks may be stuck where they are, unable to move forward, but they aren't immune to decay.

That timelessness ultimately works in favor of Wise Blood, which is one of the stranger films of John Huston's extensive career, to be sure. As I said, the only real failings come when he attempts to contemporize things. If only folks back then knew that synthesizer music came with an expiration date, they would have likely avoided it. Sometimes I feel like a broken record (there's a dated reference!) in pointing out how old films have a poignancy to our current political situations, but Wise Blood strikes as close to home now as it likely did when O'Connor first wrote her novel. Returning vets, economic hardships, overzealous religious zealots competing for who has the bigger belief--seriously, how is it that we never learn? Hazel Motes tried to teach us, but we wouldn't listen. Does that mean his failure is our own?

Friday, May 22, 2009

DRUNKEN ANGEL - #413

Akira Kurosawa's 1948 crime drama Drunken Angel is a hardboiled picture of a different hue. Not as hard as it is boiled, a lot heavier on the drama than it is the crime. Yet, like many an American gangster picture, Drunken Angel does steer its camera into the lower depths where the poor are subject to the selfish whims of thugs and gangsters. Here, though, the scenario that Kurosawa and co-writer Keinosuke Uekusa have dreamed up applies a more literal, more grave sense of life and death that exposes the meanest that the mean streets has to offer. They force their lead yakuza to question the consequences of his actions in ways that make the criminal posturing and his code of honor seem like child's play.

The Drunken Angel of the titled is an alcoholic doctor who works in the Tokyo slums. Dr. Sanada, played by Kurosawa-regular Takashi Shimura, is dedicated to helping people, even if the cantankerous old coot does need a few stiff belts off a bottle to get him through the day. Sanada is a walking, talking object lesson in making the right choices, and he drums into his patients that their continued well-being is up to them, not up to medicine or his treatments. And he should know. Sanada had very opportunity to be a successful doctor. His schoolmate, Takahama (Eitaro Shindo), runs a respected clinic not too far from Sanada's rundown offices. While Takahama was studying, Sanada was chasing women and drink. He got through his schooling, but only just, leaving him with opportunities as limited as the people he helps. In one early scene, Sanada chases a group of kids away from a toxic "lake" that they keep trying to swim in. Little more than a sinkhole, it reflects their poverty and disgrace back at them. Each man or woman who peers into its filthy waters over the course of Drunken Angel will see their life's ailment floating in the mire.

In its way, it's an ironic twist of fate. As Sanada's nurse, Miyo (Chieko Nakakita), observes, there are few doctors who are as vigilant about chasing down their patients as Sanada is, so why should he be so far removed from the resources available to the less dedicated? She knows a little bit about how Sanada is willing to go above and beyond, as she came to work for him when she had contracted VD from her yakuza boyfriend, a violent underboss named Okada (Reizaburo Yamamoto). It's been three years since Sanada first offered her shelter, on the eve of Okada being sent to jail for mutilating another man, and Sanada is still as vehemently opposed to Miyo's relationship with him now that Okada's release day approaches.

Coincidentally, the end of Okada's sentence coincides with the arrival of a new patient, and Sanada must wrestle with this obstinate intrusion. Matsunaga, played by the great Toshiro Mifune, is introduced to us in the first scene when he stumbles into Sanada's office in the middle of the night. He claims to have hurt his hand on a door, and when the doctor inquires as to why he is bleeding, he adds there was a nail sticking out of it. When Sanada pulls a bullet from Matsunaga's wrist, he notes what a funny looking nail it appears to be. Sanada has little time for hoods, and the old sot has no fear of letting said hoods know. He scolds Matsunaga and stitches his wound without using painkillers. Unfortunately, he also detects a hint of tuberculosis in the gangster's cough. When the doc suggest to the crook that he might be fatally ill, Matsunaga grows angry, leading to the first of many violent arguments between them.

Kurosawa is making no bones about how he feels about the criminal element in Drunken Angel. Though there appears to be a tendency to compare this film to film noir--the back cover goes so far as to even call it an "early noir," which doesn’t make a whole lot of sense since the movie was made in the middle of what is the traditional, and for my money only, noir period--you have to stretch the particulars pretty thin to make a connection. Drunken Angel is far more hopeful than your average noir, and though Sanada's troubled past gives him something in common with many a noir anti-hero, he is never drawn back into his wanton ways. (In fact, at the end, do we see him considering taking a bottle from the bag of the barmaid and then resisting, suggesting the doc has sobered up?) More importantly, though, for all of the "crime does not pay" sloganeering the censor board forced on Hollywood directors, there still was always an underlying glorification of the bad guys.

There is no such affection on the part of Kurosawa. Sanada acts as the director's mouthpiece, and his main objection to Matsunaga's lifestyle is that it's a cop-out. It takes more guts to stand up and take life on the chin than to bully your way through it, and the gangster is showing his true mettle, or lack thereof, in how he chooses to deal with his TB. In comparison to the teenage girl (Yoshiko Kuga) that Sanada has been helping beat her disease, Matsunaga has no guts at all. His embracing a romantically existential worldview that all men will die and you might as well go out enjoying yourself doesn't impress Sanada one bit. Not when he can follow doctor's orders and come out of the TB completely healed.

To give this message more weight, Kurosawa might have considered casting a different actor than the wolfish Mifune, whose good looks and undeniable charisma can sway even the most jaded cinephile to his side. Then again, maybe Kurosawa was aware of this, hence Sanada's lament that all the women of the area seem to fall for the yakuza despite his having nothing to offer them but misery and death. Kurosawa was giving us the rakish idol we so love, and then forcing us to watch him deteriorate. Matsunaga blows into Sanada's office like a force of nature, the Mifune wind machine turned up to full bluster. By the end of Drunken Angel, however, he has completely fallen apart. He is coughing up blood and he looks like the walking dead. Kurosawa is practically taunting his viewer. "This is the man you so worshipped?" He is helped by the fact that Takashi Shimura is one of the few actors that could hold his own opposite Mifune, and this is just one of many couplings of the two under Kurosawa's authority. The two actors balance each other out well. Shimura is grounded and soothingly predictable whereas Mifune is wild and loose.

There is an interesting criss-cross in the middle of Drunken Angel. Though Sanada has spent the first half of the picture trying to convince Matsunaga to submit to his age and wisdom, he stubbornly refuses until midway. As he does, another older man enters the scene and schools another younger man. Throughout the early part of the movie, a man (Sachio Sakai) has been sitting across the way from Sanada's office and playing his guitar, providing a live score for the movie. Just as Matsunaga is giving in to Sanada, the newly sprung Okada is demanding the guitarist hand over his instrument. He announces his return by playing his favorite song, something called "Killer's Lullaby," and instructing the guitarist that it's a song he should learn. It's a forceful entrance and a forceful move, Okada asserting his influence with quiet words and understated gestures, seemingly succeeding where Sanada's shouting insistence has failed. Okada's arrival signals a shift. He will also be taking control of Matsunaga, and Drunken Angel will now see the violence that has been bubbling under the surface of its poisonous lake emerge.

From here, the movie essentially becomes a wrestling match for Matsunaga's life. Will he go with the doctor and make the smart, healthy decision, or will he let Okada destroy him? The fabled yakuza honor is quickly exposed when Okada takes Matsunaga's girl, the cocktail dancer Nanae (Michiyo Kogure)--though at least we get a pretty wild dance-off in the process! In another reversal, Matsunaga stands up to protect Okada's former lady, Miyo, from the abuser. Matsunaga's ejection from the organization is proof positive of everything Sanada has been saying about the men his troublesome patient chooses to associate with. There is no loyalty, no values, just selfish gain. To further drive this home, Kurosawa choreographs the knife fight between Matsunaga and Okada as a slow, clumsy series of tumbles and falls. Matsunaga can barely keep from vomiting, and Okada is cowardly and comical. The sequence purposely lacks dazzle, with Kurosawa only getting flashy when he pulls off an amazing dolly shot chasing a fleeing Matsunaga down a hallway; thus, the most animated emotion in the whole battle is fear. When faced with the real possibility of death, the tough guy isn't so tough. He spills a paint bucket, and he and Okada slip and slide in it, staining themselves with their own shame.

In the end, then, it's Doctor Sanada who perseveres, as bittersweet as that survival may be. As the one man who is true to himself, accepting his fate and his failure but still struggling against the tide of his own perceived nature, he can't accept the loss of any patient. Sure, there is still the schoolgirl whose clear x-ray strikes a balance that Sanada should be happy with, but his joy, however authentic, still seems a little forced. Which I guess is maybe one place where the noir tag might fit. A noir ending, when it goes right, is only a grain of goodness on a beach of badness. It's a victory of the here and now, and singular to those who have achieved it, but like Sanada and the schoolgirl, it disappears in the crowd as the rest of humanity struggles on.

Saturday, May 16, 2009

PIGS, PIMPS, AND PROSTITUTES: 3 FILMS BY SHOHEI IMAMURA - #471

The provocatively titled Pigs, Pimps, and Prostitutes, the new 3 Films by Shohei Imamura boxed set from Criterion, is good on its promise and has all three of those things, and given that, the set could almost have the additional subtitle, "What's Not to Love?" Indeed, within its covers are three entertaining films that are also intellectually stimulating, comedically lurid, and masterfully crafted. Imamura, a seasoned professional who has made films as varied as the comically perverted The Pornographers and Warm Water Under a Red Bridge

The set opens with the 1961 feature Pigs and Battleships (108 minutes), a dark comedy mash-up about young love and the criminal lifestyle in post-War Japan. Set portside in Yokosuka, the squalid town rotates around the presence of American Navy men and their nearby station. The economy appears to be fueled by satisfying the pleasures of the occupiers, with the local men running gambling and protection rackets, as well as a healthy black market. Many of the women are part of the extensive prostitution business, entertaining sailors in dank backroom brothels and, if luck strikes, becoming high-paid exclusive mistresses.

Enter into this scene our young Romeo, a small-time hustler named Kinta (Hiroyuki Nagato). Kinta is in the gang of a yakuza underboss with perpetual stomach problems, and part of a criminal consortium moving into the pig farming business. This could be Kinta's ticket to the big time, with a fat bonus promised when the swine are sold; that, or if the cops find the body of a recently whacked chiseler, Kinta is expected to take the rap for the group as a less happy step toward his new position. A twitchy little dude, Kinta is ready to do what it takes to be a big gangster, whereas his girlfriend, Haruko (Jitsuko Yoshimura), wishes he would just chill out and run away with her, setting up a normal life somewhere else. This would rescue her from the family pressure to take a gig as a kept woman for one of the Americans, a sacrifice her mother and cousin would love her to make. She would do the work, they'd reap the rewards.

Imamura shot Pigs and Battleships on the vibrant streets of Yokosuka (and some very detailed, convincing sets), capturing a constantly active stream of people flowing through the alleys, guys like Kinta out on the pavement trying to lure drunken Americans into temptation. Lying somewhere between the inner-city slum pictures of old Hollywood and the more contemporary urban hustler flicks, Pigs and Battleships is, in a broad sense, the story of people doing what they have to do to survive. Imamura's political allegiance is understated to a degree, but not hard to figure out. The Americans are portrayed as pushy and lecherous, and the Japanese are all too quick to sell out. The gangsters prey on their own, attempts to buck the system or *gasp!* unionize are squashed, and prospects are dim. The alternatives that Haruko offers Kinta aren't all that appealing. Factory work? A restaurant? But hustling is much more fun! Hiroyuki Nagato is a charismatic actor, and Kinta's fumbling attempts at being the big shot are both endearing and frustrating. It's hard not to feel for Haruko, whom Jitsuko Yoshimura imbues with a clench-jawed independence. She is fierce in her desire, but she is blocked at every turn. By extension, we can surmise that perhaps Imamura has a similar frustration with his countrymen. I am sure Kinta wasn't outfitted in a jacket with the word "Japan" emblazoned across its back for nothing. These immoral, opportunistic men are the pigs, and they are turning Japan into their sty.

That jacket, and the rest of the more symbolic set-ups, are just the clothes the director and writer Hisashi Yamanouchi are dressing their plot in. At its center, Pigs and Battleships is a fun crime picture, with the hapless gangsters never quite getting it right. Discarded corpses wash back up at their doorsteps, they have practically bankrupted most of their cash cows (and those cows are getting restless), and they keep getting swindled when trying to secure feed for their hogs. Imamura underscores this with Toshiro Mayuzumi's score, which is often dramatically bombastic and regularly reminiscent of old Hollywood. Neither man is afraid to playfully hit those moviegoer buttons. They know what a well-placed upswell of horns and strings can do to the audience.

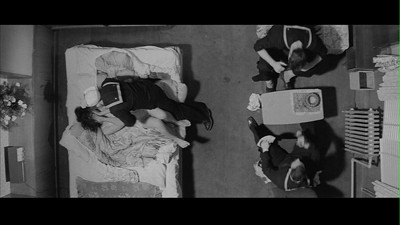

At the same time, while Imamura keeps his viewer comfortable by cradling him in the traditional, his film work is also incredibly innovative. Cinematographer Shinsaku Himeda's on-the-street shooting style brings to mind Godard's Breathless (Kinta is the goofball little brother to Belmondo), but Imamura is more daring than his French contemporaries when it comes to more rigorous breaks in formalism. Carefully manicured shots use camera movement to create a more emotional reaction. In particular, I am thinking of a scene where Haruko gets herself in trouble with three American Navy men. When it becomes clear that this is a situation that she cannot get out of, Imamura adds to the feeling of her being trapped by lifting his camera off the ground, peering down from a god's-eye point of view, and spinning the room on the screen, first this way, then that, before going into a dizzying whirl. There are many such moments in Pigs and Battleships, where the director wipes away the comedy to shove our faces into the more serious things that are at stake here. It's not all fun and games.

This technique of balancing the comic and the serious, the heavy and the light, seems to be inherent in most of Shohei Imamura's work, and it shows up again in the second film here, The Insect Woman (1963; 123 minutes), a biography of one woman, chronicling her descent into prostitution. Written by Imamura with Keiji Hasebe (Punishment Room, Temple of the Golden Pavilion), The Insect Woman once again juggles the funny with the tragic, with a little added sense of the grotesque mixed in for good measure.

Tome Matsuki (Sachiko Hidari) is born in 1918 into a sham marriage. The town slut (Sumie Sasaki) has tricked Chuji (Kazuo Kitamura), a none-too-bright peasant, into taking her as a wife, and two months later Tome is born. The film immediately jumps ahead a handful of years to show mom up to her old tricks again and the young Tome spying her in the barn with her lover. It's an important scene in the girl's life, and The Insect Woman is constructed of many such scenes. The script is really a string of vignettes, an outline of the life lived. Each shift in time or story is signaled by a freeze-frame, a title card indicating the date and voiceover featuring remembered dialogue or entries from Tome's diary punctuating the scene. These frozen moments can be wryly knowing or disappointing and sad, and sometimes all of that at once.

The Insect Woman traces Tome's development from her inappropriately close early relationship with her dad to a woman willing to stand up for herself (refusing to be kept by the landlord's son) but also showing a propensity to take a fall after swallowing a slick line (her manager at the factory beds her, convinces her to rally the workers into a labor union, and then throws her under the bus when he gets promoted). Her rape by the rejected son of the landowner produces a daughter, Nobuko (Jitsuko Yoshimura), whom Tome first leaves with grandpa during the war years as a temporary measure to make money in the next town over. Post-war, though, this stopgap measure turns into an extended journey in search of more work. This hunt leads her to religion, Imamura skewering modern selfishness by inventing a cult where one must only speak their sins out loud in order to have them forgiven. (How Catholic!) Willfully blind to reality, Tome makes herself the target of an enterprising madam (Tani Kitabayashi), who picks her up at the church and puts her to work in her "hotel." Only Tome eventually sells the madam down the river and takes over the business herself.

Imamura is using a delicate satirical thread here, sewing it through all of these phases of Tome's life and then bringing it around back to the start. Eventually, Tome becomes the kind of boss she despises, and by extension, her own mother. The girls she manages sell her out, and then her own daughter proves to be a cagier fox than the one that bore her. Without putting too fine a point on it, the director is connecting Tome's struggles, her moral compromises, and her eventual downfall, with the politics of the changing times. By the early 1960s, the get-what-you-can years of post-War occupation is giving way to a more independently minded Japan. The youth have no use for Tome's old ways, and even her daughter is scheming for a future working for herself rather than one selling herself (though, a little salesmanship is required to get seed money). Sachiko Hidari plays Tome at every age, effortlessly transitioning from a young girl wanting to do right by her father (while also sticking it to her selfish relatives) to an older woman seeking to only serve herself, to an even older woman who has been bilked, swindled, and abandoned, and insists she did all that she did for the good of others.

Again, her struggles can be funny, but they can also be pitiful and sad. There is something tragic in Tome's arc, but also something honorable. In the end, she doesn't give up. The final shot of her climbing a mountain mirrors the title card shot of a bug climbing up its own seemingly insurmountable hill. Is this evolution? A snapshot of the human condition? Feminism in Japan? One shoe covered in mud, one broken, but one must still imagine Sisyphus happy.

Some of the tell-tale aesthetic signs already apparent in the earlier movies don't take very long to show up in Intentions of Murder (1964; 153 minutes). The freeze frame returns, starting the picture with a montage of still photos, almost like we are looking at "before" images of a crime scene. Later, as the technique resurfaces, we get the same light touch in terms of music, as well as instances of meditative voiceover similar to that in The Insect Woman. The camerawork is also growing insistent again, with spins like the ones in Pigs and Battleships and amazing tracking shots, including following a young boy in the market, working on three levels as his mother flees and tugs him along, the boy looking back at the man that pursues them.

Which kind of makes it sound like a Hitchcockian thriller or something, which it most certainly is not--though there is a similar macabre sense of humor, a fascination with the secrecy and movement of trains, an interest in voyeurism, and the repeated use of reflective surfaces as tools for characters to peer into their own psychosis (most memorably, the bottom of an iron). An Imamura heroine is different than a Hitchcock heroine, however, and so whatever the psychosis, far removed from a Hitch ice princess. Sadako (Masumi Harukawa) is plump and dowdy, the shy sort-of wife to Riichi Takahashi (Ko Nishimura). Sent to his family to be their maid, working off an old ancestral debt, Sadako is in the clutches of a man who, like many an Imamura villain before him, has a rather loose definition of what constitutes a household chore, and Riichi takes his liberties with the young girl. For the superstitious, and as revealed in scenes containing shades of the witch segments of Macbeth), this hex is a continuation of a curse that has lingered over the Takahashi household since Sadako's grandmother, the mistress of Riichi's grandfather, decided she would be second best to no one. Ancient mistakes are repeated, and all the male descendents are of poor health. Riichi has a persistent cough, and the son he had with Sadako, Masaru (Toshihiko Hino), is frail and...well, not an illness, but he's also petulant.

Sadako has quietly accepted her life as Riichi's glorified servant, including not rocking the boat about their lack of a marriage. Things change, though, when an intruder (Shigeru Tsuyuguchi) breaks into the house when Sadako is alone, and instead of robbing the place and going, rapes her. An odd fellow, he first rolls over and cries before tossing money at his victim and warning her not to tell anyone. Though this troubles Sadako, she thinks she can get through the pain and the shame, but when her attacker keeps showing up and eventually starts to profess his love, this gets harder and harder to do.

The men don't get off all that easily in any of these movies, but Intentions of Murder seems particularly disgusted with that side of the human species. Once again written by Imamura and Hasebe, from a story by Shinji Fujiwara (A Colt is My Passport and Blackmail Is My Life

Besides being a thief and a rapist, Sadako's attacker has a variety of other problems. The lowlife works at nights playing drums in a strip club, blaming such a demeaning job on the fatal heart condition that he is trying to inject with enough life to take a last shot at romance. It's a rather on-the-nose ailment, the would-be Don Juan with a heart that doesn't work right. He's got mommy issues, as well, crying his heart out to Sadako about his mom the hooker who never loved him. Clearly, both of these men want to take the maternal tenderness they always felt denied them, even if by force. In the same way that Riichi's mistress drifts to him because she sees a man she can push around, so too do these men gravitate to Sadako for the mother she could be. (Compare this to Tome in The Insect Woman, who also has infantile men vying to suckle at her breast, and whose main later-in-life relationship comes with "mama/papa" nicknames.)

The only problem is that Sadako already has a boy that she really is mother to, and the overall arc of her character is to accept her rightful role as his primary caregiver, which includes the very real action of having the Takahashi family registry changed to reflect that she is his birth mother. All of the actions she takes in the movie--the consideration of suicide, the possible flight to Tokyo, the murder plot against the intruder--are steps toward Sadako's independence. In a way, Intentions of Murder resembles a battered-woman-escapes-type drama, what with the way Sadako has been hoarding money to buy her freedom and the acts of desperation that almost derail that. Imamura has better things in mind for the girl than a violent showdown with her abuser, however; he'd rather she grow into her own for real.

All of this is unfurled with the same deft and teasing hand as we've come to expect from the director in the first two films in Pigs, Pimps, and Prostitutes: 3 Films by Shohei Imamura, except with an even more assured sophistication. Imamura never telegraphs his next move, but always keeps the viewer guessing. Though he shares some of Sadako's inner thoughts with us, they aren't there to explain further than the small moments they illuminate. Visually, he alternates his compositional framing, sometimes using an elaborate depth of field and the aforementioned reflective surfaces to show the many layers of Sadako's entrapment; these are knowingly juxtaposed with the more open scenes, including the rapist's rooftop confessions where Sadako tries to pay for her release or the landscape that surrounds a receding train, the lone woman standing at the back and watching us as she leaves. Intentions of Murder is definitely the heaviest of the films here, though not without its humor, usually throwing sharp elbows at the characters that would do its heroine wrong. The laughter makes the rest bearable, giving enough to carry the audience long enough for the girl to pick herself up and declare she's a woman.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

Sunday, May 3, 2009

THE CURIOUS CASE OF BENJAMIN BUTTON - #476

There was no movie in 2008 that I anticipated more than The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. A long gestating project, it had several formidable building blocks that really hit the right spot for me. By the time it came along, I risked drowning in my own excitement, though at least I was able to see it ahead of some of the hype. One perk of reviewing movies is that you get to see them a little earlier, often before the promotion reaches critical mass and threatens to swallow the movie whole. Had I had to wait a few more days, maybe the scales would have tipped; maybe the chatter would have combined with my already epic wishes, and the image I had of the final result would have been insurmountable, regardless of the quality of the movie.

Luckily, that did not happen, and I was as pleased by Benjamin Button as I could ever have hoped to be. At the time, I reviewed it for DVD Talk, and though I gushed, I felt the movie inspired me to write a pretty good piece detailing how the movie spoke to me, how it appealed to the F. Scott Fitzgerald fanboy inside of me. This was written the night of the screening, before it would become hip to dislike Benjamin Button, and the review would become one of my most read pieces (currently #2 in terms of my personal hits on DVD Talk). When I voted in Film Comment's readers poll (I have long since sworn off a critic's top 10 of my own; too many fleas on that dog already), I put it at the top of the list with Wall*E

Often, if I review something theatrically and then revisit it on DVD, I will write a fresh review from scratch, giving my second-time-around impressions, without going back to the original review. On rare occasions, when I feel my initial reactions are as good as anything I could say a second time, I stick to the first piece. Which isn't to say I didn't take anything more out of the repeat viewing, just that my thoughts were crystal enough or my prose good enough that I am not yet ready to get around to the other side. This time, I will combine a little of both, and I will begin by reprinting my original piece on The Curious Case of Benjamin Button before sharing further ruminations immediately after:

* * * *

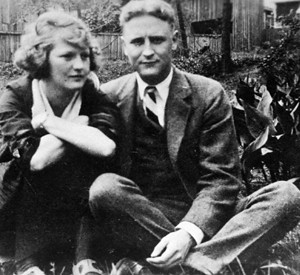

F. Scott Fitzgerald is my favorite author. His prose has a wonderful lyricism that shows a real knack for capturing the beauty in the simplest of moments. The way he composes a line can delight in its construction while breaking your heart with its vocabulary. His stories have an outer glitz that serves as a mask to the dark romanticism behind it. He always showed his readers the diamond first, and then the price it cost a man's soul second.

I don't think I've ever seen a film adaptation of Fitzgerald's that has captured that ephemeral quality of his prose--that is, not until I had seen The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Ironically, the film that pulled off this feat is the one that has the least to do with the actual source material. Outside of the title and the basic concept of a man born old and aging backwards, ending his life as a baby, the film of Benjamin Button takes virtually nothing from Fitzgerald's short story. It does, however, draw on the author's complete works in theme and tone, tackling notions of doomed romance, reinvention, and indulging in the full flavor of life. Hell, even the scenes of drunkenness feel like they could be pulled from any number of Fitzgerald's jazz age stories--or even from his biography.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button was adapted by writer Eric Roth (The Good Shepherd, Munich

Benjamin's story encompasses the whole of the 20th century. Born on the day World War I ended, we watch Benjamin travel through the Depression, WWII, and even Beatlemania and the 1980s. This is no Forrest Gump

Despite technically being the same age, when Benjamin and Daisy first meet, he is an old man and she is a little girl. Through the years, as their respective ages travel toward a common middle, the pair goes through many reunions, false starts, and misunderstandings before Benjamin finally becomes the man he wants to be and the lovers join at last. Anyone who has read The Great Gatsby

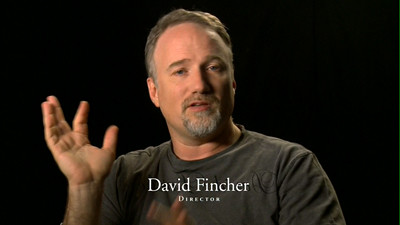

Apparently The Curious Case of Benjamin Button has been in development for nearly fifteen years. (Turns out we were spared a Ron Howard version starring John Travolta; thank God!) I imagine one of the biggest challenges was how to deal with the aging factor. Not only do we need to see old man Benjamin with a wrinkled body proportional in size to a newborn and a young child, but we also have to see him at the various ages of a full-grown man. Likewise, we have to see Daisy getting older while he gets younger. Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett are required to play both above and below their respective ages, and with the help of make-up and what I assume are some imperceptible digital effects, David Fincher has pulled it off remarkably. Though it's hard to pin them down in the ill-defined years of their 30s and 40s, when the two actors should look most like themselves, the transformation is still rather seamless. Credit is also due to both of the actors, who don't let the make-up do all the work, but who expertly walk in the shoes of different eras while maintaining the core of who they are.

It's not the only visual feat that Fincher pulls off, either. From recreating Depression-era New Orleans to the oceanic battles of World War II and 1950s Paris, the director paints across the screen like a vast canvas. A sunset witnessed by Benjamin and his ailing father (Jason Flemyng) is a gorgeous portrait of light and shadow, of water vs. sky. Equally stunning are images of burning battleships or a dancing Daisy silhouetted in night and fog. It's in these moments that Fincher captures the feeling of Fitzgerald's prose, his pictures evoking the words the way Fitzgerald's words so vividly created pictures. Similarly, the way the director uses classic film styles to reference the memories of characters in the story, including a running gag involving a man being struck by lightning, effectively simulates how Fitzgerald characters might remember times gone by through songs they loved or books they read.

At nearly three hours, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is as rich as any thick novel covering the full scope of a man's life. (By comparison, Fitzgerald did the same in a much shorter space. The short story "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button" runs twenty-two pages in my The Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald

If The Curious Case of Benjamin Button isn't the best film of 2008, it's very near the top. When it comes time for my biography to be told, I can only hope that I would have spent my time as well as this fictional character, and I can only dare to dream that it might be executed with as much grace and depth as David Fincher has achieved here. An existence well lived, a story well told--surely there is nothing greater than that.

* * * *

Reading over my review again, I don't feel my interpretation or understanding of the movie has changed, but I do think it has deepened. My first reaction on watching Benjamin Button a second time was how dark the movie is. Death is a constant in Benjamin's story, its grim pallor coloring everything (and note how darkly lit many of the scenes are, even in the pictures here). It begins with the irony of the infant starting life at an old folk's home, learning to accept death as both natural and common. It should be coming for him, it is a byproduct of his condition, but whatever spell has been cast on him has changed how death holds an individual. I guess this morbid theme should have been more obvious to me, as what I thought was an astute observation turned into a "Well, duh" situation the moment I started watching the extensive and fascinating documentary feature on the second disc of this Criterion set. The very first clip is of David Fincher talking about losing his father to cancer and the way his grappling with that became a part of the filming of the movie.

Benjamin's place in the world may have a feel-good "live every moment" lesson at its core, but there is a decidedly more pronounced intelligence than one might find in your standard second-chance post-tragedy picture. The message here is to live every moment, but accept the role age and wisdom plays in each one. If youth is wasted on the young, then don't toss away important things when you're not in a place to understand them fully. Patience is a virtue.

This is most evident in the love story, which is antithetical to the standard tales of young love that is the passionate energy of most romantic movies. Daisy offers herself to Benjamin, but he refuses her advance because it's not right yet, a rebuke she carries with her in a tight little fist in her heart, and that only likely makes sense to her years later when, while convalescing after an accident, she rejects Benjamin, choosing instead to wait until she is herself again. Benjamin wanted her to be strong enough and wise enough to love him with more than an impulsive schoolgirl lust; this carries over into her wanting to love him only when she can be her own self-sufficient person.

Meeting in the middle is less about being physically compatible, but more about being mentally compatible. Like wine, let this romance ferment. The risk, of course, is that they will grow apart, and thought it's a risk all lovers must take, for them it is a fait accompli. As Benjamin was able to be a young man learning from the old, however, Daisy will have the reverse position, being able to learn from him as he grows young. Both are taught to savor the things that matter by seeing the way others are losing their grip on those things. In Daisy's case, it must be more bittersweet for bringing her experience as a mother to taking care of Benjamin as his life ebbs. He is just a baby when he passes, having forgotten all he learned, the complete opposite to the baby daughter Daisy raised, whose every day was a new experience.

It's not a romantic ending, certainly not in terms of their relationship. Benjamin didn't really have mother issues; if he was seeking a mother surrogate to replace Queenie, he didn't realize it. If that was his reason for connecting with Daisy, it was a primal instinct, an act of self-preservation. The saddest scene in the movie is not a physical death, but an emotional one. It's when Benjamin, now in his early 20s, has come to see a middle-aged Daisy one last time, and she ends up going to his hotel room. The compulsion, as one might read it on Cate Blanchett's face, is to feel the passion again, to see if it's still there; the disappointment, again conveyed largely through expression and body language by Blanchett, is that it's not. The romance has died.

Or again, just matured, transmuted to something else, love of a different bloom. This is really the meaning in the much-maligned metaphor of the hummingbird, which possibly chafes some reviewers because its function is more literary than cinematic, the visual maybe needing a prose back-up to convey its full power. It's not that everything is connected, but that all life is transformative, continuous, the energy goes on. If Captain Mike (Jared Harris) has become a hummingbird after dying in the U-Boat attack, then it's a moment out of Ovid

When you boil it down, all of Benjamin's encounters and re-encounters involve stories. Everyone has their own, and Benjamin is the catalyst for each person telling it. In some cases, he is the reason they finish the narrative, such as Tilda Swinton's character finally returning to swim the English Channel (as it were, defying the flood rather than succumbing). Daisy is sharing the tale with her daughter--and truly sharing, the daughter reading it aloud to soothe her dying mother while also taking it into herself. Even when the story can't always be trusted, such as the mixed-up memories of the residents of Queenie's old folks home, they are still part of the mythology. More often than not, those stories are full of hurt and sharing them is part of overcoming; life is all about mourning, the grieving process for what could not be and what we know will come. I think one missed opportunity here was that the man who was always getting hit by lightning should have told eight or nine different versions of the strikes while still claiming to have only been hit seven times. The point being that it would be no less true, not as long as it's true to him. Queenie believed the faith healer helped Benjamin to walk, and that brought her comfort. Nick Carraway felt the same of Jay Gatsby--he is the man he said he was, and thus better than the whole damn lot of them.

You will believe, through the magic of moviemaking, that a man can be born old and die young.

Because then, wouldn't we also have the go-ahead to question the veracity of Benjamin's own story, the diary being read aloud and forming the movie? It, too, could be invention. It's all invention, really. A child aging backwards, a hummingbird in a war zone, seven bolts of lightning. Taking a hold of the story could give one the power to command it, to take over life's quirks and coincidences. Isn't that the point of the story of Daisy's accident, told in an expertly paced, rapid mis-en-scene by Fincher, to say if just one piece could be rearranged, then death could be cheated further?

Which brings me back to story again: you can't die if your narrative is preserved between the covers of a book or on a two-disc DVD set. Watching the talking heads sharing the production tales on disc two definitely gives one some fulfillment in terms of a need for preservation: we were here, we did the work, here is how that happened. The fact that they approached their movie storytelling in such a classic, tried-and-true manner is like the gift they give to us, returning us to what's important about shared experience. The future meets the past, technology enables tradition. Fincher embraces old cinematic and literary styles and integrates them in with his new way of doing things.

When I first saw The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, I saw it with one of my favorite friends and my most ardent collaborator, and by chance, we both rewatched the movie on the same night, too. When we saw each other the next day, we discussed our new impressions, and she mentioned the scene where Benjamin and his father are talking, before Benjamin knows that he is a Button, and the son tells the father that old age isn't so bad, it's nothing to fear, its routine is not crushing. In fact, in narration earlier, he notes that the routine is liberating, clearing the way for the mind to sit and ponder other things (how very Zen!). In the end, it is the simplest truth of all: if you can get through that, you can get through this. If you can survive the teen years and the perils of adult life, you can survive a well-earned retirement. If you can grow up, you can grow old.

Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)