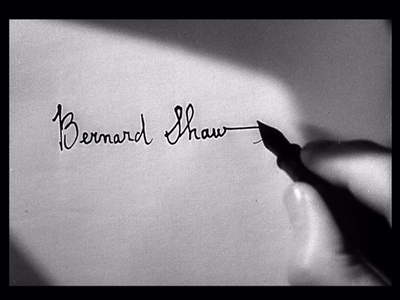

George Bernard Shaw was one of the pre-eminent playwrights of the late 1800s and early 20th Century. He is one of those rare animals who were never bound by form, having written novels, short stories, and criticism in addition to his more famous stage productions. It is unsurprising then that his work would make an easy transition into the newer motion picture medium--and do so with Shaw's approval. The author impressively survived to see the ripe age of 94, finally passing on in 1950. He even won an Oscar in 1938 for his contribution to the adaptation of maybe his most famous play,

Pygmalion.

Pygmalion was produced by Gabriel Pascal, and it was part of a fruitful collaboration between the two men. In fact, after

Pygmalion, Pascal, who had begun his career making silent films in Germany, only produced Shaw adaptations, and the remainder of his film career is represented in the three films in this boxed set,

George Bernard Shaw on Film - Eclipse Series 20. His devotion to Shaw was often as much of an albatross around the filmmaker's neck as it was a boon. Shaw even encouraged Pascal to expand his horizons prior to his death, but the director/producer only outlived his beloved writer by four years.

The movies in

George Bernard Shaw on Film - Eclipse Series 20 span eleven years, 1942 to 1952. They consist of one wartime love story and two historical movies, one an epic and the other an allegorical comedy. They are linked only in as much as they came from the same mind. Shaw had an interest in human nature, and he was particularly fascinated by and critical of inconsistencies in behavior. From a Salvation Army mistress intent on rescuing the lost from eternal punishment to the vagaries of kings and man's limited capacity for beliefs other than his own, Shaw dissected hypocrisies with a clever wit and often withering disdain.

Major Barbara (121 minutes) was made in 1941. It is an updated version of Shaw's 1905 play, brought into modern times, and though the signs of WWII are everywhere--much of the sets show the damage done in the Blitz, and in fact were shot

during those attacks--the actual war is mentioned little. The Major is not in the fighting forces, but a soldier in the Salvation Army. Played by the wonderful Wendy Hiller, who also starred in

Pygmalion, she is a firm believer in every man's right to earn forgiveness in the eyes of God. Fearless and forthright, she has yet to meet the sinner who can stand up to her. Even the cynical scholar in Greek classics, the unfortunately named Adolphus Cusins (Rex Harrison, who starred in the

Pygmalion retooling

My Fair Lady years later), is willing to go along, drumming in the Army band just to be close to his new fiancée.

Barbara also has the distinction of being the eldest daughter in the Undershaft family, a well-to-do clan whose estranged father has gathered their fortunes from the spoils of conflict: he manufactures cannons. When Andrew Undershaft (Robert Morley) returns to settle some family business, he is challenged by his daughter give her religious lifestyle a serious look. He challenges her in return to consider taking over his factory. When daddy and a whiskey magnate donate heavily to the Salvation Army, bailing it out of its economic tailspin, it challenges Barbara's belief in what it takes to set right one's soul.

Major Barbara begins with a handwritten letter from Shaw, asking audiences to trust his vision and see his film, which was directed by Gabriel Pascal with assistance by David Lean and cinematography by Ronald Neame, as a parable. Indeed, much of what happens is abstracted from real life, and except for the juxtaposition of the war-torn backdrop, there is little here that is not purely cinematic invention. Which isn't meant to say it doesn't strike some actual emotional chords; Shaw understands this canvas better than any other, and he builds a large cast that not only includes the Undershafts, but gets into the lives of the people Barbara intends to help. She squares off with Bill Walker, a cockney bruiser played by Robert Newton, who suggests there are more practical concerns in the here and now that take precedence over the hereafter.

The film takes a strange turn in its third act. After Barbara rejects her rank, daddy offers her an alternative: she can believe in industry. The Undershafts and Adolphus visit his factory, and we see all the steel products the symbolically named Undershaft and Lazarus manufacture--not just the end product, but we also see footage of the mills at work. Andrew Undershaft has built a community for his workers, a kind of modern utopia where families live and toil in one big compound. It's not exactly socialism, more of a moralistic capitalism, and when Barabara sees even Bill can get on the straight and narrow once he's got something to do with his hands, she envisions a whole new avenue for rescuing men from damnation.

This ending is a bizarre mix of patriotism, capitalistic propaganda, and pro-worker jingoism that is pretty close to Bolshevism. (Adolphus is also rallying for workers rights at the start of the picture, which is its own bizarre story point.) It's hard to know how to take it, though, because there is almost an ironic falseness to it. In the last shot, you practically expect Hiller, Harrison, and Newton to wink at us. How much of this is satire? It's weird and over the top, a la Tony Richardson's

The Loved One

(still more than 20 years off). It left me scratching my head.

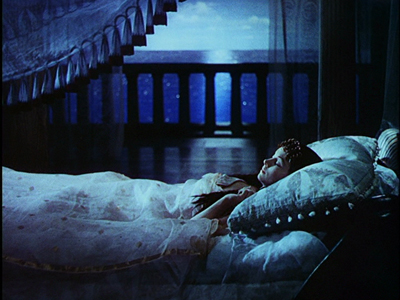

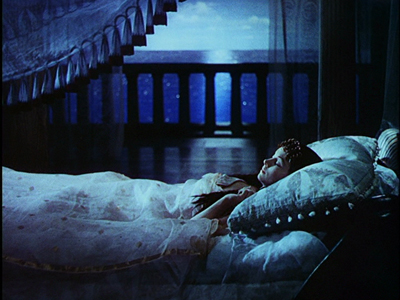

It also didn't really matter. Though most of the cast is pretty much playing stock roles, Wendy Hiller is so good as Major Barbara, the script is practically secondary. She's plucky and attractive, but she moves Barbara away from being a type and into something more authentic after her break with faith. Scenes of her alone, contemplating her heart as a bombed-out London sits in shadow behind her, make the whole movie seem rich and complex where once it came off as a mere trifle.

As perplexing as some of the ending of

Major Barbara might be, I'd give up clarity for good not to have to sit through

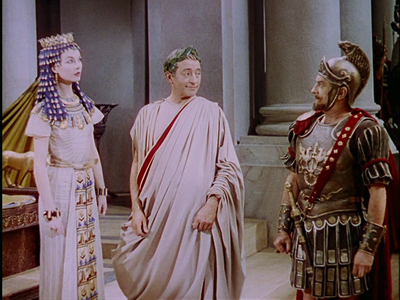

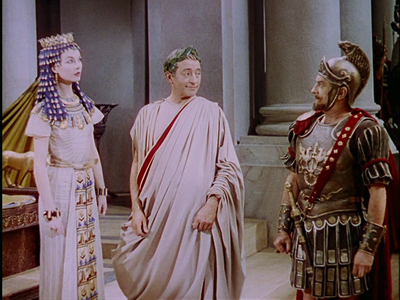

Caesar and Cleopatra (1945; 128 minutes) again. Once again directed by Pascal, it is based on a play written by Shaw at the turn of the century. The historical pageant is the story of how Julius Caesar (a sleepwalking Claude Rains) went to Egypt and met the precocious, overgrown adolescent Cleopatra (Vivien Leigh, on loan from David O'Selznick, as her credit tells us). The fearful Egyptians flee before the Roman might, convinced they are cannibals, and they somehow let their queen run off by herself to hide inside the Sphinx. To add insult to the improbable, Caesar meets her when she interrupts his soliloquy to the monument. He is smitten with her ditzy ranting, and takes her under his wing.

As far as epics go,

Caesar and Cleopatra lacks any blood or thunder. The gears of war are clogged in red tape. Caesar roams around stating his case with a blithe vocabulary. The Egyptians say he will never rule, Cleo's tween brother is the true king; the occupying Roman army that came before Caesar says they'll keep the country they've conquered for themselves instead. Meanwhile, a Sicilian artist named Apollodorus (Stewart Granger) wanders in and out of scene, sporting a tan and bleached teeth, looking like he's misplaced his surfing movie. There's a lot of talking, but not much seems to be said. The script has traded wit for circular conversation. It's all a ghastly bore, as Caesar's British slave might say.

I can see what must have appealed about the original script. Cleopatra has an interesting arc, learning to be a political animal under Caesar's Mr. Miyagi-style tutelage. He laughs at her silly schemes, sprinkles a few homilies like fairy dust, and then walks away so she can simmer in the message. By the end of the movie, she's no longer cowering behind his skirt, but instead sending her scary witch (Flora Robson) to kill her rivals. Vivien Leigh is pretty terrible in the role, however. The writing does all the growing for her. Her performance as young Cleopatra consists of wide eyes and bubbly tones; adult Cleopatra scowls and speaks with a hiss. Pascal's production is just as false. The Technicolor spectacle never really looks convincing. Its grandeur is that of a backlot set.

Apropos of nothing, though maybe it serves as its own commentary on

Caesar and Cleopatra, after I finished watching the DVD, I left the still menu sitting on the TV screen while I got my computer and prepared some food, etc. I left it up for about five minutes before I realized the pug I was babysitting was barking at it and not something outside on the street. Was it the color of yellow on the graphic, irking him like a red rag to a bull? Or was he just so sick of seeing Claude Rains and Vivien Leigh, he couldn't stand anymore? Not sure where he gets off if it's the latter, since he got to sleep through most of the movie.

There's a theory, most notably advanced by Orson Welles, that color is not the filmmaker's friend, that it exposes blemishes and distracts from the essentials. Perhaps that's part of

Caesar and Cleopatra's problem, because the other Roman drama in this set, 1952's

Androcles and the Lion (98 minutes), and its black-and-white rebuilding of the Coliseum works in all sorts of wonderful ways.

Gabriel Pascal takes a backseat here, still smarting from the box office failure of

Caesar and Cleopatra (the seven years between productions, apparently, was not by choice). Chester Erskine (

A Girl in Every Port) takes over directorial duties, adapting the Bernard Shaw play with co-writer Ken Englund. They've brought the story to life with a light comedic touch. Alan Young, who is probably most famous as the owner of the talking horse on

Mr. Ed, was typecast as a lover of animals from the get-go. He plays Androcles, a big fan of furry creatures and a persecuted Christian who is the top of an alphabetical list of Jesus freaks sentenced to a date with the lions. While on the run, the gentle and bumbling tailor runs across one of those dreaded lions in the wilderness. Said king of the jungle has a thorn in his paw. Androcles removes that thorn, he and the big cat become friends, and Androcles even names him Tommy.

Androcles is arrested shortly thereafter, joining a band of merry Christian soldiers on a trek to Rome and the Coliseum. They travel under the guidance of a stern but thoughtful legionnaire, known only as Captain (Victor Mature). These curiously happy prisoners make him curious about what makes them so joyful, especially when one of them turns out to be a rather attractive damsel. Lavinia (Jean Simmons) is a true believer who takes no guff but is truly tender-hearted. Also amongst the group is Ferrovius, a bruiser with a crazy reputation. He apparently is quite the effective missionary, though his methods may be slightly off script. He is played by Robert Newton, who does the same Keith Moon impression here as he did in

Major Barbara (though, I guess it's more likely that Moonie nicked the routine from him, given that Keith wouldn't even have picked up a pair of drumsticks yet). His testimonials are a highlight of

Androcles and the Lion, and his character is far more interesting than Simmons's. She is merely a pretty face, and the romantic subplot with her and the Captain is predictable and shallow. Alan Young is the humorous glue of the piece. He orbits the other characters, adding corny asides, biding his time until the climax when he is reunited with Tommy. Their tango in the gladiatorial ring is funny in good ways and bad. The editing is really poor, making it painfully obvious that Young isn't actually with the lion most of the time, and the guy in the lion suit when the two of them quite literally dance is unintentionally hysterical.

Androcles and the Lion is kind of an odd duck. On one hand, it's pretty good secular entertainment; on the other hand, it wears its messages on its sleeve. That message is less pro-Christian than it is pro-tolerance. In fact, the heavier the Christian rhetoric, the more clumsy it seems, particularly given the anachronistic nature of much of what is said. Though Shaw's play dates back to 1912, the fable's message against persecuting people for their ideas and beliefs is one that was fairly common in 1950s pop culture. Shaw disliked hypocrites, and the verbal victories that Lavinia and Ferrovius win throughout the movie are usually in pointing out how their persecutors could just as easily have their own religion turned against them were they not in power. Androcles's love of all animals is meant to promote a respect for all living things, a respect that was often lacking in the contemporary political climate (as it often is now).

The scenes where Androcles's faith is tested on the arena dirt are actually pretty powerful, at least before the dance sequence. The movie goes on a little too long after that, everyone missing their cue to exit, but

Androcles and the Lion is still an amusing distraction. I found myself laughing enough to forgive its quaint foibles, and it makes a fine companion to

Major Barbara, even if we must take

Caesar and Cleopatra in the middle.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.