In keeping with their mission statement, Criterion's

Eclipse series once again brings together a collection of neglected films in a no-frills package in hopes of giving new life to material left by the wayside. In addition to their fantastic bundlings of films from well-known directors, the series has also created a space for more obscure creative powers. Early in the run, Eclipse released two masterworks by pioneering French filmmaker

Raymond Bernard; last summer, they introduced a lot of us to the pleasures of Russian auteur

Larisa Shepitko; and now four entries later, they unearth a quartet of early Japanese films by Hiroshi Shimizu.

Travels with Hiroshi Shimizu - Eclipse Series 15 is one of those delightful eye-openers that only come along once or twice a year, the kind of thing that surprises and dazzles the uninitiated and leaves those already in the know nodding their heads and wondering what took us all so long. A graduate of the earliest days of the Japanese studio system, Shimizu was a working director. IMDB's listing for the man lists a whopping forty-two films made between 1924 and 1957, though in the liner notes in this set, Michael Koresky posits that he made upwards of 150; from what I can tell, these are the first to ever be on DVD in the United States. It's one of the few cases where I wished the Eclipse Series actually did have an extra DVD bonus or two. I'd love a documentary feature to tell me where Hiroshi Shimizu came from and even more importantly, why he disappeared.

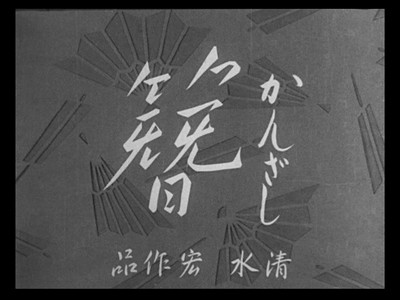

Travels with Hiroshi Shimizu starts of with a bit of a whisper. The 1933 silent film

Japanese Girls at the Harbor (76 minutes) is a minor melodrama and may cause you to wonder at first what all the fuss is about. The script, adapted by Shimizu from a story by Toma Kitabayashi, is fairly typical. In the seaside town of Yokohama, schoolgirl Sunako (Oikawa Michiko) falls for local bad boy (Ureo Egawa). He goes by the name of Henry, a modern pretension that likely should have signaled to Sunako what kind of guy he is. He likes to hang out with gangsters and chase a little action on the side, namely a much faster girl named Yoko (Ranko Sawa). In a fit of rage, Sunako attacks her rival, leading to her exile out of town and the life of a bar geisha. By chance, she runs into Henry again, and he's now married to her school chum, Dora (Yukiko Inoue). Will Sunako learn from their happiness and get her own life back on track, or will she once again claim her man?

There aren't many narrative surprises in

Japanese Girls at the Harbor. The Sunako character and thus, the resolution, really can only go one of two ways, and it doesn't take much to figure out who her mysterious neighbor is. What makes the film important, however, is the style that is already beginning to emerge. Shimizu displays an assured facility with the camera as well as a natural sense of framing. His mise-en-scene has a modern aesthetic in terms of his switching between close-ups and longer shots. He has an observational eye that is simultaneously inquisitive and attentive and a developing sense of movement. Outdoor shots at the waterfront, in particular, take on an almost contradictory intimacy in the way the director stands back and follows Dora and Sunako and watches their estrangement grow. They are practically silhouettes, yet their body language and the way the landscape isolates them lays their souls bare.

Shimizu also uses jumpy editing instead of a conventional zoom in revelatory scenes. Rather than one smooth push, he cuts from one camera position to the next, leaping closer to his guilty subject. I suppose the rough edits, harsh and almost violent in the evident physical damage to the film, are indicative of how ahead of his time he was, that he was maybe a couple of jumps ahead of the technology, too.

The three years between

Japanese Girls at the Harbor and

Mr. Thank You (1936; 78 mins.) might as well have been three decades given the degrees of sophistication that separate the two films. Criterion skips over at least six notches in Shimizu's belt to get from there to here, and in that time Shimizu had also made the switch from silents to talkies--though the sound era was enough of a new development that his working class cast of characters still aren't entirely sure what talkies are when the subject comes up.

Based on a story by the wonderful Japanese author

Yasunari Kawabata, the titular

Mr. Thank You is an overly polite bus driver (Ken Uehara) who shuttles townsfolk up and down the mountain where they live. His name comes from his habit of loudly thanking people along the way who step aside to let his vehicle pass, and the film follows him over the course of a day as he drives from the village at the top of the mountain to the train station at the bottom. Set during an economic depression, the passengers are all concerned with their various states of poverty, unemployment, and social standing. Mr. Thank You has driven many of the local girls down the mountain that have never made the return trip, sold into factory work or prostitution in order to help their families pay the bills.

One such girl on this trip is an innocent seventeen-year-old (Mayumi Tsukiji) heading to the train with her mother (Kaoru Futaba), where the two will reluctantly say good-bye. We don't know for sure what exactly is happening to the girl at first, but the true meaning of her journey is largely sussed out by the one other female traveler on the bus, a worldly drifter (Michiko Kuwano). Be it her innocence or her perceived ruin, the girl draws the attention of the men on the bus, including that of the driver, who over the course of the trip woos the girl in ways even he doesn't realize until they are pointed out to him.

Mr. Thank You is a film of constant motion. Whether Shimizu's camera follows the bus, peers out its windows, or catches the background as it passes while focusing on the interior passengers, we are always traveling. Quite effectively, Shimizu even puts us on the road, barreling down on the pedestrians whom Mr. Thank You must pass, and then dissolving to them as they walk away and the driver shouts his gratitude. In one way, we are watching the downward momentum of people on their way to various states of ruin, but in a much more hopeful way, we are also seeing how roads and transit are connecting people in a manner that was never possible before. The bus driver is a benevolent figure who knows everyone along his route, who isn't at all reluctant to do a favor like pass on a message or pick something up at a shop the next town down.

Nowhere is there a better symbol of the two sides of transport, the consequence of progress, than the sweet young road worker that Mr. Thank You stops to say farewell to. She was part of a crew of Korean immigrants building the mountainous path, but now that it's done, she is moving on to the next assignment. Though her hands went into changing the land, she can't afford the bus fare to enjoy the fruits of her labor in a modern style. Likewise, her father died while the progress was being made, and she must leave his grave behind in this foreign land to continue working elsewhere--the new leaving the old, the price of advancement, and also the plight of society's most marginalized individuals all rolled into one bittersweet package.

Comparing Hiroshi Shimizu to

Max Ophuls may be a bit of a stretch, but there is something reminiscent of Ophuls' dizzying, constantly moving camerawork and the way Shimizu keeps his own story going forward while also making sure to turn and look at what is going by. Both unmoor their cameras in order to show the movement of life, but also to drink it all in and not miss a single detail. They both also have a true affection for the characters they capture, and in

Mr. Thank You, Shimizu's portrait of the poverty stricken and their perseverance is sweet, hopeful, and positively endearing.

Two blind masseurs walk into a vacation spa...

Despite all the movement in

Mr. Thank You, and though this next film does open with a marvelous tracking shot where the camera is always several steps in front of its main characters as they walk up a mountain road, Shimizu puts his camera down for

The Masseurs and a Woman (1938; 66 mins.). He continues his interest in chronicling the smaller details of lives not normally chronicled, but within the confines of the mountain hotels where much of the action in

The Masseurs and a Woman takes place, it's better to sit still, pick a vantage point just beyond the edge of the room, and watch.

Though the title does sound like the premise for a dirty joke, I assure you, it is not. Two blind men working as traveling masseurs (Shin Tokudaiji and Shinichi Himori) spend their summers in a mountain resort servicing the guests. One of them, Tokuichi, is so obsessed with his own mobility, he makes every walking trip into a race, counting the number of people he can pass on the road. Possessed of an incredible sensory perception, he can also determine who is near as they approach. Just by her smell, for instance, he can detect that one of the women on a passing carriage is from Tokyo. When that woman, Michiko (Mieko Takamine), finds these things out, she becomes intrigued by the man and his special skill set.

The masseur, Tokuichi, is intrigued in return, and he even develops a bit of a crush. Already self-conscious about his blindness, these feelings of love are further complicated by the woman's growing friendship with another man (Shin Saburi) visiting the resort, as well as a mysterious rash of robberies that seem to occur wherever the woman also goes. Are Toku's suspicions of Michiko valid or simply the result of his confused desire? When the truth is revealed, Shimizu, who also authored the script, yet again shows a tremendous sensitivity to the role of women in Japanese society at the time.

He also shows a tremendous appreciation for natural environments. In all four of these movies, the director used real locations to add a realistic character to his films. The mountain retreat of

The Masseurs and a Woman is idyllic, and Shimizu takes his characters out to the streams and into the woods and photographs them amidst all the wonders to be found there. This realism gives an added oomph to the simple honesty of the story, which is at turns humorous, intriguing, and poignant.

You can also see the filmmaker's technique continue to improve. The jumpy zooms of

Japanese Girls at the Harbor are used again in

The Masseurs and a Woman, this time moving in on two pairs of feet in flight. Gone are the rough splices, replaced with smooth moves from one shot to the next. Fittingly, the movie also ends on another traveling shot, the camera once again in motion. This time, however, instead of preceding the walking masseurs, it follows a departing carriage, peering around a bend to wave good-bye.

The final film in the box,

Ornamental Hairpin (1941; 70 mins.), also takes place at a seasonal mountain resort. A group of travelers come together for a summer amongst nature, and they find their tranquil retreat upset by the regular arrival of new and larger groups of vacationers. At the opening, it is a group of geisha, their presence on the road flanked by tall trees reminiscent of the start of

The Masseurs and a Woman. Their noisy partying and sapping of the hotel's services annoy the other patrons, particularly a grumpy professor (Tatsuo Saito). Even after they are gone, their presence is felt, as a soldier on furlough, Nanmura (Chishu Ryu), steps on a hairpin left behind in the bath. When the owner, Emi (Kinuyo Tanaka), learns that he has been hobbled by her lost accessory, she returns to help him recover.

Love appears to be a foregone conclusion for these two. Nanmura dismisses his injury as an act of fate, likening the hairpin to poetry and claiming it is verse that has pieced his sole. Whether he realizes it or not, his group of new friends, which includes a married couple as well as an old man and his two grandsons, speculate over whether the pin's owner will be beautiful. When Emi arrives, they all concur that she is, and a quiet affection quickly grows between her and her victim as she watches him rehabilitate. All have seemed to forget that she was with the geisha, and only a few brief references to her past life remind us that she was not living a common existence back in Tokyo. Rejecting her newfound life of simplicity to return to the commitments she ran out on hangs heavily over her, becoming the thing that can be worried about instead of worrying about the ongoing war, itself alluded to less than even Emi's forsaken profession.

There is a sense of playful abandon in Shimizu's careening through the forest with his characters.

Ornamental Hairpin is episodic in structure, a blustery anecdote of the professor saying something pompous here, the young boys busting that pomposity with a joke there. Subtle hints of class creep in, particularly since most of the central guests are sharing rooms and eating rationed food to get cheaper rates, while the Hiroyasu couple (Shinchi Himori and Hideko Mimura) is able to afford their own room and upgraded meals. At the center of it all, though, is the love story, though it's one only told in glances, in the space in between. The only open display of any affection is when Emi carries Nanmura on her back to help him the rest of the way when he is trying to traverse a rickety bridge as part of his challenge to walk on the hurt foot. Again, Shimizu is tipping his hat to the shifting roles amongst the sexes, to the added burden that women have begun to carry.

Though all of his films have a bright demeanor and a glass-half-full optimism, there is also a practicality to the features in

Travels with Hiroshi Shimizu. There is always a sense that contentment is being lost, that advances are made in trade of something fundamentally good. As time wore on for the director, his stories seem to suggest that there is less of a chance for societal salvation. All of these movies end with some kind personal transformation for one character or another, but in both

Japanese Girls at the Harbor and

Mr. Thank You, there was also an element of community rallying around the one who needed redemption. That community is reduced to a duo in

The Masseurs and a Woman, and the promise of a new life is something that lays beyond the conclusion of the film and even then, without the two who see the change being together. So, too, are the would-be lovers in

Ornamental Hairpin kept apart. For Emi to free herself of all the things that bring her down, she must stay out of Tokyo, even when Nanmura returns there. She has happiness, but it's not without tears. Their plight surely mirrors that of many wartime affairs.

Though the first shot of

Ornamental Hairpin is wide and contains the many, the last shot is closer in and contains a single person. Even so, it's Emi climbing the same steps that Nanmura had to climb to prove he was healed, and so too is she proving that she is whole again.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.