This marks a year now of doing weekly reviews for this site. Since last Christmas, I've maintained my goal of one new Criterion review a week, either exclusively for the site or cross-posted with DVD Talk. It wasn't always easy, and I was late a couple of times, but I don't want to be a fly-by-night blogger who can't set some kind of commitment for his site and stick to it. So, cheers!

In addition to my Criterion reviews, here are other reviews film fans of similar tastes might find of interest from the last month:

IN THEATRES...

* The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, David Fincher's astounding adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald's short story of a man born old and aging backwards. Elegant, engrossing, simply amazing.

* Defiance, a cookie-cutter WWII exodus, with a standout performance from Liev Schreiber but little else to distinguish it.

* Doubt, from stage to screen, John Patrick Shanley's drama about suspicious activity at a Catholic school provokes and impresses.

* Revolutionary Road, a brutal tale of a loveless marriage, directed by Sam Mendes and brought to emotionally devastating life by Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslett.

* Waltz With Bashir, an animated documentary about the Lebanon War. Yes, it's as interesting as it sounds.

* The Wrestler, wherein Mickey Rourke redeems a career squandered, Marisa Tomei proves she is still phenomenal, and Darren Aronofsky pulls back on the style and shows us how good of a storyteller he can be.

ON DVD...

* Burn After Reading, the Coens lead a phenomenal cast through a darkly comic, impenetrable plot. Loved it so much, I watched it again the day after I reviewed it.

* DJ Spooky's Rebirth of a Nation, a disappointing experiment in cinematic remixing that never gets beyond the concept stage.

* Frost/Nixon: The Original Watergate Interviews, the program that inspired the new movie.

* Generation Kill, the complete Frost-Simon HBO series about the early days of the Iraq War.

* The Who at Kilburn: 1977, two-discs of monster rock!

HAPPY NEW YEAR, EVERYONE!

Wednesday, December 31, 2008

Monday, December 22, 2008

MONSTERS & MADMEN (#364): THE ATOMIC SUBMARINE - #366

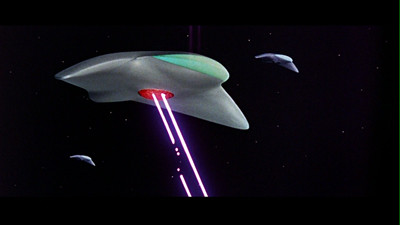

It seems backward to me that a fake rocket shooting through fake stars would look more convincing than a fake submarine drifting through a simulated Arctic sea, but comparing First Man Into Space with its companion picture, The Atomic Submarine, I'll be damned if that isn't the case. Perhaps it's the preponderance of fishbowls and all of their plastic accoutrements in real life, or perhaps it's that we all know what it looks like under the water and the fact that the U.S.S. Tiger Shark never actually gets wet that makes it hard to not see the effects in The Atomic Submarine for what they are. A plastic toy and wavy lighting makes for a tough sell, even in a campy, retro sense.

It also doesn't help that the bad guy in The Atomic Submarine has had his bizarre image supplanted by a far better known pop-cultural force.

The plot of The Atomic Submarine is this: Some unknown assailant or force has been destroying U.S. subs working under the North Pole. Not just any subs, either, but nuclear subs. Intent on stopping whatever it is, the government sends their top craft, the Tiger Shark, to find out what is causing the mayhem. Armed with a couple of extra scientists, as well as a joyriding pacifist who has invented a special diving craft with his father, the men of the Tiger Shark head out to sea. Once in the Arctic Circle, they encounter a malevolent saucer with a single staring "eye," which they then dub Cyclops. Unable to shoot it out of the water, they try to ram the ship, getting the sub's prow stuck in its hull. The pacifist, Dr. Carl Neilsen (Brett Halsey), and his tough-guy nemesis, Commander Richard "Reef" Holloway (Arthur Franz), board the Cyclops with three expendable men, hoping to pull their nose out of the Cyclops' butt. Once on board, Reef encounters the thing that is piloting the killer craft and uncovers what is really going on.

What is really going on is that aliens are looking to colonize Earth, and the single creature at the helm of the aptly named Cyclops is a one-eyed, many-tentacled extra-terrestrial. He first makes his presence known as a voice appearing in Reef's head, and upon hearing John Hilliard's dubbing, I immediately thought of Kang and Kodos, the alien invaders from The Simpsons. Little did I suspect that when I actually saw the Cyclops pilot, he would also look like Kang and Kodos. Mere coincidence? Possibly. Kang and Kodos were apparently based on an old EC sci-fi comic, and who knows? Maybe Irving Block and his team of effects men were inspired by the same comic book.

Of the four movies in the Monsters and Madmen boxed set, The Atomic Submarine is easily the bottom of the stack. I'm all for preposterous stories, but the design of the interior of the alien machine lacks any internal logic, and the way the Tiger Shark defeats the invader puts an unbearable weight on one's suspension of disbelief. Not even the ham-fisted dichotomy between the pacifist and the warrior doesn't geta its full due. Despite the final scene of the movie being a wistful moment shared by Neilsen and Reef--on land, and lit like its daytime on the ground in direct opposition to the starry sky that brings the men pause--the filmmakers don't even go for the obvious pay-off, driving home that despite Nielsen's previous distrust of the military, he now sees that there is a need for vigilance. Somewhere out there is a great threat, and it will take men like Reef to keep the planet safe from harm. Take that, you peace loving science guy!

It will also take better men than we see here to make a decent adventure movie about space-age submarines. Then again, I just may have a pitch for the guys at The Simpsons. I know how to work Kang and Kodos into the 2009 Treehouse of Horror!

Thursday, December 18, 2008

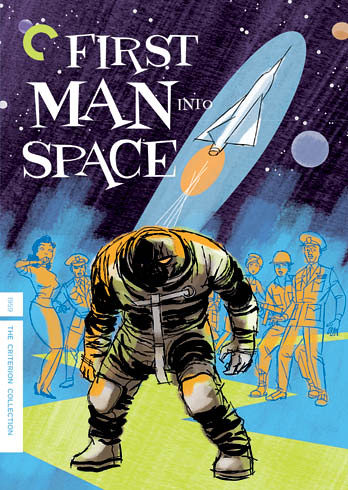

MONSTERS & MADMEN (#364): FIRST MAN INTO SPACE - #365

Inspired by the good time of reviewing Robinson Crusoe on Mars last week, as well as enjoying the irony of exploring the vastness of outer space while being snowed in for an especially chilly Oregon winter, I decided this week to watch another old sci-fi film, First Man Into Space. It's part of the Monsters & Madmen collection, the Darwyn Cooke cover art for which is currently featured as a limited edition print in the Criterion store.

Though during my October horror fest I had reviewed the spookier titles from Monsters & Madmen, I hadn't yet sampled the more space-age selections. Directed by Robert Day, from a story by Wyott Ordung and a screenplay by John C. Cooper and Lance Z. Hargreaves (what names these guys have!), First Man Into Space is of the same hopeful yet cautious ilk as other 1950s astronaut movies. Released in 1959, two years after Laika had gone into orbit, the movie raises the next logical question: how do we get a human being up there?

Well, it kind of asks the question. Though many of the sci-fi chillers of the 1950s carried a secret message, either about the effects of Communism or even the dangers of meddling with forces beyond our scope in the Atomic Age, one really has to force a square peg into a round hole to divine a greater meaning out of First Man Into Space. Sure, there are cursory reminders to remember the human element in our efforts to perfect machines, and one could possibly argue for a message regarding the double-edges of nature. It helps us when we need it, but not heeding its lesson could cause our downfall. Yet, to get such a lesson out of the flick is probably only possible if you really want to learn one, and I'm guessing the filmmakers aren't really expecting you to bother.

First Man Into Space is about a pair of brothers who work in an unspecified experimental technology and space-focused division of the U.S. Navy. The logical and precise Commander Charles Prescott (Marshall Thompson) works in the control tower, while his brother, Lieutenant Dan Prescott (Bill Edwards), is a test pilot, so by nature daring and prone to straying off mission. Film technology even establishes another unintentional division between the pair: for some reason, all of Edwards' dialogue was re-recorded in ADR, giving it a flat quality lacking in ambient tones, while Thompson's dialogue has the echo and cadence reflective of the natural space of the wherever he is at. Ironically, those are kind of backwards, since Charles is more the machine and Dan the unpredictable force, but then again, if we want to find a lesson, these boys do end up crossing over each other by film's end. So perhaps we it's not to be too much of one and stay open to the possibility of the other?

The movie begins with Dan taking off in a new rocket. The basic dynamic of ground control and flight mission is already in place, even in 1959, with the action jumping back and forth between the guy being shot into the sky in a tin can and the people on Earth trying to keep him alive. Dan pushes his plane to the limit, going as high as he can, and ultimately falling back to Earth and narrowly escaping death. Not one to wait for a rescue team, he hauls ass into town to hook up with his “babe,” the saucy yet oddly melancholy Italian scientist Tia Francesca (Marla Landi). Charles wants to go over the details of the mission, and Dan wants to go over the details of Tia.

Dan's derring-do gets him noticed by the media, so against Charles' wishes, his brother is put in the pilot's chair for the next mission. This time, Dan goes past the 250-mile mark, getting cut off from base and once again plummeting back to Earth--but this time bailing from the rocket in the nose cone. When the escape capsule is found, Dan is gone, and in his stead there is a strange, rocky protective coating around the shell of his craft. There are also some suspicious-looking cows slaughtered in the farmer's field Dan landed in, but until a monster starts leaving bodies in the town nearby, no connection between the crash and the bovine dead is made.

As it turns out, the protective coating not only covered the spaceship, but it has covered Dan, as well, turning him into an indestructible space vampire thirsty for blood. Since he can drive a car, Charles and Tia realize that some kind of intelligence, some semblance of the man they knew, must be left in that lumbering Golem from the cosmos, but how to stop his murder spree before the Navy and local police insist on stopping him?

The transformed astronaut isn't much of a monster. He is just a guy in some kind of body covering suit, like he's been wrapped in a rubber recreation of the surface of the moon or something. As a creature of destruction, he's not very convincing, and if it wasn't for the explanation of the destructive power of the substance that surrounds him--on its own, it's flexible and harmless; add force, and it's hard and deadly--there'd be no reason for everyone to stay out of his way like they do. Just hit him with something heavy and knock him over!

Much more impressive are the special effects simulating outer space. Dan's rocket is a convincing model, and his tailspin at the start of the picture, with an animated planet Earth doing loop-dee-loops across the screen, is actually pretty cool. It's kind of too bad that there wasn't more of that, because I was really digging the rocket adventure. I'm sure some of this might have been budget constraints--the rampage of a man in a cheap suit costs less than rocket fuel--but then again, it fits the weird dichotomy of the times, anyway. Like so many other sci-fi movies of the early space age, First Man Into Space is both hopeful about the future but strangely naïve about what it might mean. The technology is rudimentary, the consequences still rooted in superstition. Things go bump in the night, and to expand the night to include the whole of the galaxy just means we're inviting those bumpy things back here.

Or maybe First Man Into Space is just harmless fun, with no lesson at all. Either way works for me!

Friday, December 12, 2008

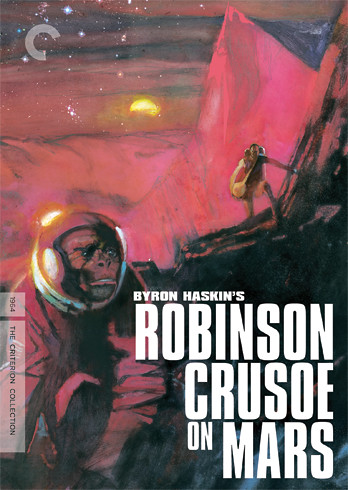

ROBINSON CRUSOE ON MARS - #404

When Criterion announced earlier this week that they were selling some drool-worthy limited edition prints of some of their more illustration-driven covers, it seemed a good excuse to rummage through my shelves and pull out one of the featured movies that I had never seen before. This ruled out my choice for the print I would most like to have given the spare cash*, Jaime Hernandez's depiction of Divorce, Italian Style. It also disqualifies Amarcord, leaving the more sci-fi themed selections for me to choose from--a couple of movies still in the Monsters & Madmen boxed set and Byron Haskin's 1964 special effects adventure, Robinson Crusoe on Mars.

Robinson Crusoe on Mars is exactly what it sounds like, a fun re-imagining of the Daniel Defoe novel

For the first half of the picture, it's just Kit and Mona learning to survive. They must figure out how to produce heat, where to find food and water, and how to keep breathing in the low-grade Martian atmosphere. Kit builds a camp, records his thoughts, and generally does whatever he can to keep from going crazy. The second half of Robinson Crusoe on Mars involves Kit discovering he is not alone. A malevolent alien race is mining the planet, using humanoid slaves they've captured on a world somewhere in Orion's Belt. Kit ends up helping one of the slaves escape, and in an open nod to the Crusoe story, he names him Friday (Victor Lundin). They become friends, and when the slave-owning aliens return to pick up their lost property, the trio of men and monkey make a run through underground canals and across perilous deserts to reach the polar ice caps.

There is no great storytelling innovation in terms of the well-worn Defoe narrative. In fact, from what I know of the original, I think they may have shaved a little of the deeper meaning out of it when they shot it into outer orbit. The alien Friday being white definitely softens the whole "brotherhood" aspect of the story, while the unspecified reason for the Earthmen's visit to space means there isn't any discussion of colonialism. A very basic religious message arises as both men move toward the middle to find some common understanding, but that is about it.

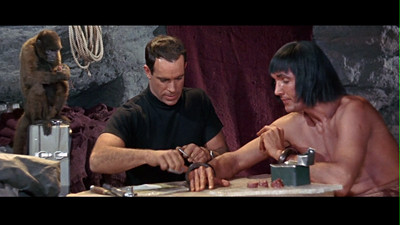

What has replaced the larger social meaning is Haskin's unrestrained imagination. Using a combination of models, traditional animation, and life-sized sets, Haskin creates the illusion of space travel and Mars in jaw-dropping detail. Though arguably coming off a bit kitsch now that more than forty years of moviemaking have passed, even compared to today's computer generated graphics, the scope of Haskin's inventiveness is pretty much impossible to miss. It fills every inch of every frame. Tubes of paste simulating steak and onions, oxygen-producing coal, and loin-clothed slave aliens that look like they are ready to start building the pyramids--no cliché of early space-race sci-fi is left unturned. Yet, once you surrender to the fun and wonder that Haskin intended to inspire, there is no going back. I was pretty much hooked as soon as I saw the monkey in a spacesuit clinging to the spaceship wall like he was floating in zero gravity. When haven't boys been suckers for monkeys?

Not being a sci-fi connoisseur, I'm not exactly sure whether to classify Robinson Crusoe on Mars as surprisingly progressive or charmingly naïve. Haskin's view of the future seems rooted in the same safe and clean predictions that were being made in the movies of the 1950s, yet the mission of Draper and McReady, as well as their monkey sidekick, does show a knowledge of the space race. Regardless of whether the vision of the future was progressive or not, the cinematic realization of it was, and Haskin's effects-heavy Robinson Crusoe is lively, colorful, and meticulous. I am sure many a budding filmmaker watched this film and saw a vast horizon of possibilities opening up, and the movie likely endures because it still inspires such awe.

This makes comics artist Bill Sienkiewicz an equally inspired choice to provide cover art for Robinson Crusoe on Mars. Sienkiewicz entered the mainstream comics scene in the mid-1980s, when I was an adolescent reading my first comics. Though his early work displayed a realism inspired by Neal Adams and Daredevil-era Frank Miller, Sienkiewicz quickly switched up his style. When he was assigned to the X-Men spin-off The New Mutants

I am not afraid to admit, I hated Sienkiewicz's work when I first saw it, just as I hated most experimental comic art at the time. My puny brain was not yet developed enough to understand it. Yet, there was something about his work that made it hard to turn away from, and when he collaborated with Frank Miller on Daredevil: Love and War

Which is not dissimilar to what Byron Haskin was doing with the Saturday matinee sci-fi film. He was taking an accepted sci-fi style and at once retrograding it by slipping it in the familiar loincloth of Robinson Crusoe and shoving it forward by using abstracted effects and radical visual ideas to create a more immersive reality.

For those who may be more interested in Bill Sienkiewicz, Image Comics just recently republished his masterwork. Stray Toasters

* If I was really sporting some disposable cash, I would actually buy the original artwork from the other Pietro Germi film in the Criterion library. My buddy Mike Allred has all of his drawings for Seduced and Abandoned on sale through his art dealer, Got Super Powers. A bargain at half the price.

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

EUROPA - #454

Before Lars von Trier was part of the Dogme 95 movement, living by an avant-garde manifesto that was meant to chip away the artifice of filmmaking and adhere closer to the grittiness of real life, he was actually working on the opposite end of the spectrum. His early films were visually exciting, inventive, and challenging flights of imagination. This includes his 1991 post-War mindbender Europa (a.k.a. Zentropa), a Kafka-esque espionage adventure that tunnels its way into the bleakness of occupied Germany. Bureaucratic nightmares, rickety technology, false identities, and questionable allegiances all converge for a paranoid thriller that has as much to do with the treacherous landscape of the mind as it does our treacherous perceptions of history.

Leopold Tressler (Jean-Marc Barr) is an American sent to Frankfurt in October of 1945 to work alongside his Uncle (Ernst-Hugo Järegard) for the Zentropa Train Company. Leopold is to be a sleeping-car conductor, a clever symbol for the hypnotic journey he will soon be taking. His very occupation is that of ferrying passengers from one place to the next while they sleep. So, too, could all of Europa be a dream. We enter the movie under cover of night, a single light illuminating the train tracks that our eyes scan as the narrative voice of Max von Sydow plants the hypnotic suggestion that will transport us to Germany alongside Leopold.

Immediately upon landing at Zentropa, Leopold discovers a near impenetrable corporate system full of rules, regulations, and many a wheel that needs greasing just to get him started working. Each door he steps through requires another qualification, each person he meets further complicates the situation. Sometimes these discoveries seem part of a larger plot, sometimes they are simply extraneous wrinkles designed to push our hero further into the mire. He meets the Hartmann's, owners and operators of Zentropa--the weary father Max (Jorgen Reenberg), the gay son Lawrence (Udo Kier), and the mysterious daughter Katharina (Barbara Sukowa). Katharina first comes to Leopold on the train, claiming a fear of traveling through tunnels (paging Dr. Freud!), but then invites him over to dinner at the house, where she starts to peel away the layers of her outward persona. Katharina may have at one time been a member of the Werewolves, an insurgency of Germans trying to foil the American efforts to govern their country. Just as he is a man torn between his home country and his ethnic heritage, so is Leopold caught between the politics of a defeated Germany and the restoration/reformation efforts of the Allies. He witnesses a farce organized by the U.S. military leader Colonel Harris (Eddie Constantine) to exonerate Max Hartmann of any Nazi connections, but he is also duped by the Werewolves into making an assassination in the sleeping car possible. Leopold is so tangled up in this intrigue, he doesn't know whether he is coming or going.

Most of Europa is shot in black-and-white, evoking spy movies of the period, from Fritz Lang's pre-War homeland efforts to Orson Welles vehicles like Journey into Fear. Lars von Trier also uses exaggerated rear projection and subtle splashes of color, creating an effect that is a little something like Guy Maddin visiting Sin City

Europa is surreal in all things: technique, logic, and construction. von Trier's shooting style goes hand in hand with how the story develops, and the world that production designer Henning Bahs builds for Leopold to traverse gives it all shape. The Germany of Europa is like a wasteland, with bombed-out buildings sitting alongside labyrinthine constructs like the Zentropa worker's barracks. Interiors feel desolate, disconnected from the outside world by their decoration, at once looking like movie sets as well as the nightmarish, man-made products of war. In many ways, with the way his camera's movements homage Hitchcock and his audaciousness prefigures Baz Lurhmann, Lars von Trier is drawing a connection between the proliferation of pop culture--specifically, our obsession with movies--and our own interior anxieties. Our anguish over past misdeeds (the Nazis and World War II) comes cloaked in the iconography of old motion pictures, and these cloak-and-dagger images also bring up the lingering anxiousness of the Cold War and a fear of the unstoppable momentum of technological progress. Leopold is both a man of the world, fancying himself able to straddle two cultures, and an outsider, belonging nowhere, just as the 1990s were moving toward mass globalization where individual cultural identities were being celebrated even as the machine gobbled them up. And this was pre-Quentin Tarantino, before talking in pop cultural buzz phrases became de rigueur.

Within these echoes of movies past is Leopold's desire to belong, as well as his romantic yearnings. Katharina captures his heart even as she demands his trust. Here the "Werewolves" name is revealed to me more clever than maybe was immediately apparent: as a lover, Katharina is asking the same questions that one would ask as a monster or as a terrorist. Do you trust me not to hurt you? A commitment in any relationship begins with this question, whether it is articulated or not. And in movie fantasies, getting the girl and saving the day and coming out unscathed are all the same goal. The sticky web of romance and the sticky web of international intrigue? As Humphrey Bogart taught us, it's all the same thing.

Of course, Bogie wouldn't be as out of his element as Leopold is. The lie of the movie fantasy is that we'd be more confident in the midst of the concocted plot than we would be were it happening to us in real life. Leopold never knows what to do, is indecisive, and is subject to the caprice of those who would use him to their own ends. Caught between his desires and various regimented moralities, none of which seem right, Leopold could become hopelessly lost. To push the movie metaphor further, Katharina chastises him by saying that since he was not actually in the war, he is not really in a position to judge those who were. He hasn't lived it, he has only observed from afar, so how could he possibly understand what any of this means?

It's this accusation that pushes Leopold toward his final decision and puts the climax of Europa into motion. Leopold simultaneously becomes the voyeur and the man of action. In the foreground, he appears in color with a rifle; in the background, the black-and-white insertion of his own eyes watching him. I seem to recall similar eyeball imagery in Steven Soderbergh's Kafka (and, of course, Hitchcock's Spellbound), but in the explosive finish of von Trier's movie, he is evoking Orson Welles' movie of The Trial

Despite Lars von Trier's reputation as a difficult director, the refreshing thing about Europa's meta-narrative is that von Trier never steps so far beyond his audience that he looks back to smugly admire the intellectual distance that he has put between himself and the viewer. Rather, by wrapping this unconventional story in conventional trappings, he has created a comfortable zone for the viewers to appreciate what he is doing. The toys are familiar even if the playground is not. Thus, though Europa picks at our brain and challenges us to find our way through its maze, the way it keeps us guessing like any other wartime mystery doesn't make the puzzle-solving daunting. Rather, like the true masters of suspense, the pleasure is in the pondering, and thus it's all the more fitting that the entirety of the movie takes place all within the viewer's mind. A filmmaker is nothing but a hypnotist, after all, lulling you into a state where you believe that what you are seeing is real. (All the more fitting that von Triers' Hitchcockian cameo is as the lying Jewish collaborator who falsely exonerates Max.) To provoke, to intrigue, these are von Trier's goals, and though he would employ harsher methods in the years to come, Europa is no less stunning for the ease with which it goes down.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)