Romance is easy; breaking-up is what’s hard to do. Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 masterpiece Contempt (Le Mepris) is my favorite of all his films. It is his most emotionally raw, a carefully composed examination of marital failure, ego, and hubris. Legend is that Godard hated making the film and the American producers who hired him hated what he gave them. Yet, there is so much about that history, about the contentious nature of the set, that informs what happens onscreen, better circumstances would have only harmed the art. It’s a movie that isn’t just about the death of love, but also about the implications of artistic compromise and how such decisions inform the personal lives of the artists. It’s a movie about making movies, rife with mythological allusions. Within its context, the gods are cinema itself, and everything else is man. All too fragile, brittle man.

Contempt opens with two disparate sequences, each laying out specific elements of Godard’s mis-en-scene. First, a “behind-the-scenes” shot of cinematographer Raoul Coutard at work, filming a woman walking (the script girl played by Georgia Moll), following her with his camera, riding a track toward the viewer while Godard reads the opening credits aloud.

The second bit is a cataloguing of star Brigitte Bardot’s many attributes. She lies on a bed naked, in character as Camille, with her onscreen husband Paul (Michel Piccoli). She is vulnerable and insecure about her body, in direct opposition to our perception of the sexbomb and her reputation. In truth, the scene was Godard’s capitulation to the producers, who wanted a little sizzle to help them sell the feature. It is itself an artistic compromise, much like the ones Paul will give in to as the film progresses. The changing colors and the static filming of the scene will later be echoed in the images we see of Greek statuary. Bardot is our movie goddess. She is so revered, that merely half an hour into the film, Godard creates a montage of flashbacks reviewing everything she’s done in the previous 30 minutes. Just in case you needed reminding.

The “plot” of Contempt is rather bare. Paul is a writer who is hired by an American movie producer to rewrite an adaptation of Homer’s The Odyssey. Jeremiah Prokosch (Jack Palance) is an uncultured schlock peddler. Fritz Lang appears as himself, playing the director whom Jeremiah (or Jerry) has hired and who is now proving too artistically difficult. Jerry wants more sex and death, Lang wants to deal with the grand themes of humanity.

The story of these characters begins to parallel that of Odysseus and Penelope and the rest in a small, confined way. When Jerry meets Camille, he immediately sets his sights on her. His view of women is about as low as his respect for classic literature. His theory about The Odyssey is that Penelope cheated on Odysseus while he was away. Jerry keenly perceives that despite being there physically, Paul checked out a long time ago; thus, Camille is the Penelope waiting to be taken. As the script development progresses, Paul reveals himself in how he alters Jerry’s theory: Odysseus left for war and doesn’t rush home because he was sick of his wife. If she was unfaithful, all the better, it only proves him right. When Odysseus returns and kills his rivals, it’s really just a matter of protecting his territory and asserting his masculine rights (those terms should likely be in quotes).

For as negative a view of womanhood as this presents, I think there is a real case to be made for Contempt as a feminist movie. If we are to take Lang as the voice of reason, as well as the mouthpiece for the director, he is the only one to stand up for Penelope, and he is also kindest to Camille. In truth, Godard’s portrayal of the wife is entirely sympathetic to her problems, even if he does frame her predicament in somewhat old-fashioned terms. She is neglected and rebuked by her husband, whom she wishes would take a more traditional, masculine role in their relationship. Throughout Contempt, she is pushing him to make a decision, any decision. The worst of these times comes right after she first meets Jerry and the American contrives to separate her from Paul. She practically begs her husband not to send her off alone with him. She wants him to man up and show her that she is valuable and desired; he dismisses her instead, and when they are reunited, she appears shamed and disappointed. I know many might debate the quality of Brigitte Bardot’s acting ability, but her performance in Contempt is subtle, emotional, and mostly interior. She never really owns up to her infidelity, but she never has to: we see what she has done and gone through entirely in how she looks at her spouse.

Piccoli’s performance is just as tricky. We are never sure how much he knows or even suspects. When he arrives at Jerry’s, his story of the taxicab collision that delayed his arrival seems strangely apropos. The detailing of the car crash, in both word and gesture, is strikingly suggestive. It actually wraps Jerry’s preoccupation with sex and death into one convenient symbol, particularly when you consider what the anecdote is actually foreshadowing.

“If you love me, just be quiet.” - Camille

The centerpiece of the film immediately follows the indiscreet incident. It’s a long argument back at the couple’s apartment. The conversation lasts more than half an hour and consists entirely of the pair sniping back and forth, raising suspicions, dancing around truths, and exposing cruelties. Narratively, Godard frames much of this in film noir conventions, largely to cater to the image that Paul wants to create for himself. As we will discover, he is an intellectual bully playing at being a tough guy, and it’s telling that the one moment of true expressive honesty he has in the argument is when he strikes Camille. It’s an old-fashioned movie moment, the gangster slapping his moll. To fit in with Paul’s fantasies and also to change herself, Camille puts on a black wig and tries to be his femme fatale, but Paul rejects her; in turn, she dismantles his pose. His fedora and cigar are meant to mimic Dean Martin in Some Came Running

The argument ends with a particularly devastating exchange. In answer to Paul’s suggestion that they “make love,” Camille strips and throws herself down on their couch. She tells him to take her, but to make it quick. In the time between her begrudged offer and his refusal, Godard shows us another montage: a capsule of their whole marriage and confirmation that it is indeed falling apart. It’s a brilliant trick of time. The fight is drawn out and long, presented without break; it eclipses the whole of the rest of their union. It’s also a trick that is almost purely visual, marrying disembodied voices to structurally abstract visuals. A lot can be divined from the Coutard and Godard’s framing throughout the film. Watch how the characters come together and move apart, how physical objects divide them, or how the camera swings from one lover to the other--there is something indecisive about a lot of it, like maybe if they would just sit still, they could fix this.

It’s this argument scene that keeps bringing me back to Contempt, and why, again, it is my favorite of Godard’s films. The way the dialogue flows here is so natural, so lacking in pretension or contrivance, it never loses its rawness, no matter how many times you see it. I took on this particular viewing as research for a novel I am working on, as I am wrestling with similar themes of self-compromise and the damage lovers inflict on one another. What most impressed me about the movie this time around was not just the honesty of the writing, but how Godard lays the larger tapestry of myth and storytelling over the top of it, while also weaving the threat of violence throughout.

“Death is no resolution.” - Fritz Lang

Godard teases us with a gun early in the film. A pistol appears at Paul and Camille’s apartment, and it shows up again later in the back half of the story when the couple travels with the film production to Capri. Knowing as we do that Paul believes Odysseus asserted himself by killing Penelope’s suitors, what then can we infer that he will do to the man that made him a cuckold? In truth, Godard is subverting the old Chekhov rule about what happens when a gun appears in the first act of a drama. In what may be the cruelest cut of all, Camille takes the bullets out of the revolver before she leaves Paul, rendering him impotent. After his second abandoning of her, she leaves him with no third option.

Here, too, Fritz Lang remains the voice of clarity. He believes there is no possible good outcome from a crime of passion, and he sees altering the purity of Homer’s story as akin to messing with the shared values and principles that define us as something other than animal. As the resolution of Contempt bears out, reckless decisions bring destruction. Fate can’t be averted.

It’s funny, but when I worked at a video store from 2004 to 2007, Godard was often a topic of discussion. It was a small, privately owned store and it had sections for specific directors, so we had a clientele with tastes slightly more adventurous than what was just new or popular. Naturally, opinions about Godard were all over the place, but it wasn’t uncommon for people to tell me that they thought Contempt was boring. I find this ironic, because on the face of it, it’s one of Godard’s most accessible movies. Its narrative is the most simplistic, there is an obvious three-act structure, and its situations are easily relatable. Perhaps without the varnish of the usual Godard technique, without his playfulness and pranksterism, the presentation was too naked, the heft of the assault too much to carry. Belmondo in Breathless [review] can play at being Bogart and get shot down in the street, and we never forget it’s a movie; in Contempt, no shot is ever fired, not from Piccoli’s gun or at him, and so there is nothing to break the illusion that this is real pain and real life.

“Like Brigitte Bardot

In Godard's Le Mepris

I can't love you enough

To make you complete

You appear in my dreams

With some new courtier

You need me there to see

What you need to convey”

- Pete Townshend, “It’s Not Enough” (recorded by the Who, 2006)

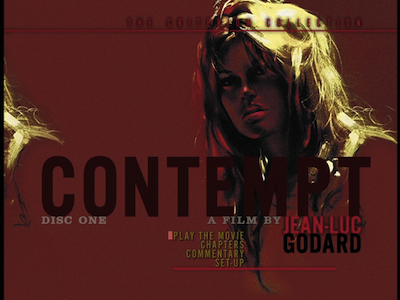

My collaborator and friend Joëlle Jones did the above drawing for a collector. He specifically requested Brigitte Bardot from Contempt. I think it turned out pretty awesome. You should check Joëlle's work out over at her blog.

* Other possible entries in this particularly happy-go-lucky film festival are Mike Nichols’ Closer

No comments:

Post a Comment