"The tragedy of your time, my young friends, is that you may get exactly what you want." - Factory Owner, Head

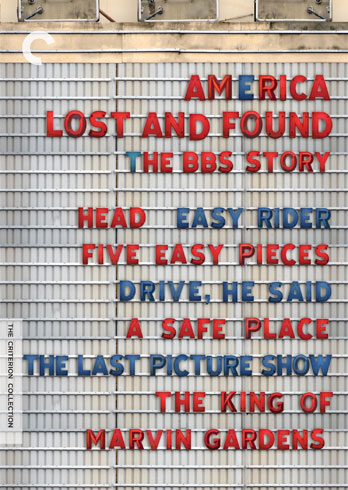

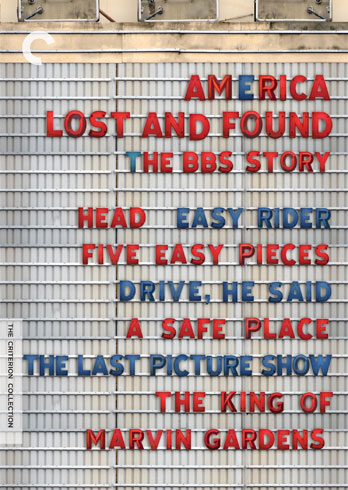

BBS was a short-lived, yet artistically progressive production company that had an integral role in one of the most adventurous periods of American moviemaking. Comprised of Bob Rafelson, Bert Schneider, and Steve Blauner, the company made seven movies in the late 1960s and early '70s, some of which went on to be iconic works, some of which are not as well known. Each were distinguished by the team's commitment to working with new talent to show contemporary America as they saw it, from the working class through to the counter-culture and on up to the moneyed folks. That is why the boxed set of these movies is called

America Lost and Found. The BBS productions were chronicling a turning point in modern living, and their films were saying good-bye to an old, glossed-over Hollywood vision and hello to something more liberating.

In fact, you can see the struggle for the creative torch played out in the set's first and possibly most perplexing film,

Head (1968). Directed by Bob Rafelson, and featuring scripting by none other than Jack Nicholson,

Head is, of course, best known as the movie that featured the Monkees sending up their own image and addressing the critical misconceptions directly, but doing so in their inimitable madcap style.

I have always liked

Head, though I have never been able to convince myself if it's actually good or not. It's entertaining and funny and full of great songs, but it's also maybe too long and too self-reflexive. At times, it feels like all involved are telling a joke only they are in on. Yet, the squeaky-clean television Beatles were breaking out of the box that broadcast their scripted adventures week after week.

Head showed them doing things they couldn't do on TV, including Peter Tork hitting a woman and then wondering if that was something he could get away with. As he tells us, he is "always the dummy." Is he even allowed to search his soul to question the assigned morality?

The freeform collection of skits runs through movie history, flaunting clichés while addressing political and artistic concerns, melding social issues with the Monkees' insistence that they were authentic while also exposing the artificiality of their cinematic construct.

Of course the group's heartthrob Davy Jones would be paired with America's sweetheart Annette Funicello, but he'd reject her to sing Harry Nilsson. The more obvious metaphor of old Hollywood vs. new, however, is the giant Victor Mature that chases the Monkees through the whole movie. In one scene, they are the dandruff in his oily hair; in another, the overly tanned actor is bored by their antics; in the end, he is one of the elements that chases them to their death. The question is, did he know that the cultural shift

Head represented would actually be the cause of his own demise? The days of the Hollywood star system than made Victor Mature a celebrity were over.

Possibly not, especially since

Head was not a box office or critical success. I doubt, then, there was much hope for the next BBS picture a year later:

Easy Rider (1969). Directed by Dennis Hopper, and co-written by Hopper, Peter Fonda, and satirist Terry Southern (

The Loved One

), it was a road picture, a collection of vignettes strung along a map, following two motorcycle hippies on their journey from a West Coast drug deal to Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Fonda plays Captain America, the flag-draped picture of laid-back cool, and Hopper is Billy, the spacey, long-haired cowboy that cruises alongside him. Wherever the pair go, they are met with resentment and distrust. It was the counter-culture directly meeting exactly what they were counter to, though in a lot of ways, they are far more sympathetic to the other side than Old America is to them.

Jack Nicholson appears in a memorable supporting role, playing an alcoholic lawyer the bikers meet in jail and take along with them on the rest of their trip. He lays it out for the Captain and Billy: they represent true freedom, and their rejection of the expected social paradigms exposes how the old democracy stifled individuality. Hopper and Fonda were taking the cheap B-movie, Hell's Angels-exploitation pictures they had been making for Roger Corman and, like the Monkees, flipping what was expected and injecting it with the unexpected. It's a pretty heavy-handed message, and it has a pretty heavy-handed outcome. And I hate to say it, despite the excellent performances, I actually find

Easy Rider kind of boring. It's the sort of movie I can appreciate for its significance, but that maybe isn't as artistically potent now that some time has passed.

Excepting that, Hopper's directorial approach is impressively innovative. Legendary cinematographer Lázló Kovács shot the movie using a naturalistic lighting style, photographing the locations as they were; however, Hopper took this realistic-looking footage, and he and editor Donn Cambern cut it like a psychedelic movie. Transitions show flashes of things to come, like channel surfing into the future, be it the future that is just around the corner or further down. Hopper also uses contemporary music in a far more pronounced way than was common at the time. Whole songs match whole stretches of highway, with the two guys and their bikes rolling to the rhythm of Steppenwolf, the Band, the Byrds, and others. Granted, it's these extended "music video" sequences that can make

Easy Rider drag, but you know, you can't win them all.

And let's face it: historically

Easy Rider was a big hit, and it lead to BBS garnering more faith in their material from studios. This lead to a creative explosion, as the newly successful conglomerate set out to give fresh talent the avenue to realize their vision. First up, Rafelson and Nicholson (and Kovács) reteam for

Five Easy Pieces (1970). Thankfully, third time is the charm, here is where they get it just right.

Five Easy Pieces was developed from various scripts by Rafelson, with the final product cobbled together by Carole Eastman (credited as Adrien Joyce). It's a movie that everyone thinks they know before they see it, based on one iconic scene--Jack Nicholson, diner, hold the chicken salad between your knees--but the complete film is really so much more. Yes, Jack plays Robert Eroica Dupea, the kind of motor-mouthed, half-cracked crazy that is his raison d'être, and in a way, it is the definitive revelation of so much Jack to come. Yet, as his pretentious name hints, there are layers to Robert. Though we meet him working as a roughneck in the oil fields of California, his return home to the Washington wilderness will be a journey of rediscovery and revelation. His middle name is for Beethoven's 3rd Symphony, and he is from a family of classic pianists. Bob himself can tickle the ivories, though he walked away from that and has been hiding out amongst the working class. He is only returning to his clan because his father may be dying.

What works so well in

Five Easy Pieces is that odd pacing of real life that

Easy Rider strove for and maybe didn't quite get. The way the story unfolds appears to be haphazard, as if there is no plan, it's only when you get to the movie's emotional climax that we realize that Rafelson and Eastman are building to something. The early part of the movie shows Robert's happenstance life, screwing around with his drinking buddy (Billy "Green" Bush) and screwing around on his girlfriend, Rayette (Karen Black, a BBS regular; she is also in

Easy Rider). Ray goes with him on his drive North, and endures the pedantic hitchhikers they pick up (Helena Kallianiotes and Toni Basil), and eventually insinuates herself into the family situation. Robert is trying to keep his two lives separate, which is the worst symptom of his condition. He is a man trying to outrun his emotions, not just his pedigree, and

Five Easy Pieces is when they catch up with him. The title is a little mysterious, but it has connections to how Robert squanders and cheats his true talents by playing the easiest music he knows.

Lázló Kovács' photography is once again the star here, and his underplayed style suits the dusty oil fields as much as it does the rain drenched Northwest forestry. His work here brings to mind the dirty photography of his pal Vilmos Zsigmond in Robert Altman's

McCabe & Mrs. Miller

, not just for its lack of a glamorous color palette, but also for how he manages to create an uneasy alliance between the environment and the people. It is a relationship both parasitic and symbiotic, the humans don't quite fit and yet they must to survive. This serves Rafelson's metaphor: Robert is playing at being something he is not, and in the final scenes, he strips down and unintentionally removes his protection from the cold. It's a move of surrender, but one that means he can get back in touch with what is true about who he is and where he belongs.

Jack Nicholson is riveting in the lead. He is starting to develop that Nicholson persona, but what will be the tricks of his trade are so dialed down here, they still have the spontaneity that some later performances maybe lack. In his most incisive performances, Nicholson plays the anti-hero whose bravado is really just an illusory suit of armor, and a good director works with him to get beyond it. Again, it's the metaphor I just mentioned, of getting past the clothes and getting to the man. The actor has an impressive monologue in the film's heartbreaking climax, and despite the attention of the diner scene, his farewell to his father is really Jack Nicholson at his best.

"You're pretty. And sad. And weird as hell." - Fred, A Safe PlaceFor as progressive and individual as all the films in

America Lost and Found: The BBS Story can be, the true odd ducks emerge midway through the set, paired on one disc.

Drive, He Said (1970) and

A Safe Place (1971) are the two least-known movies here, largely because they haven't been on home video prior to this boxed set. It's not hard to see why, they aren't exactly commercial screamers. Still, they are fascinating curios, and they speak to the artistic freedom Schneider, Rafelson, and Blauner extended their talent.

Drive, He Said is Jack Nicholson's directorial debut. The actor doesn't appear in the movie, but he co-wrote the script with Jeremy Larner, adapting Larner's novel. (Some sources say that

Chinatown

-scribe Robert Towne, who appears in the film as Karen Black's husband, and none other than Terence Malick also contributed to the screenplay.) The story follows two college roommates, stoned-out basketball player Hector (William Teppert) and unhinged political activist Gabriel (Michael Margotta). Hector is likely to be drafted to the NBA, Gabriel is fighting being drafted into the army; the former is indecisive and unsure of his future, whereas the latter is ready to push the boundaries and break free. Unsurprisingly, only one of them ends up making any definitive moves.

In an interview on the disc, Nicholson says that making

Drive, He Said taught him that to successfully adapt an impressionistic work of fiction, the key is to remove any interior monologue. If something only happens in a character's head, it has to go. That may be the way to do it, I don't know; I can't say that

Drive, He Said is entirely successful. Some of it works really well--the May-December romance between Hector and a teacher's wife (Karen Black) rings true, and Bruce Dern runs away with the movie as Hector's coach--but other parts fall flat. Particularly, Gabriel's theatrical protests struck me as pretentious and not very believable. While Nicholson was trying to harness the energy of unrest on college campuses, what he puts on screen comes off as staged and false. Like

If.... [

review] with its fangs filed down. Luckily, the emotions of the individual characters still feel real, and the plot continues to be relevant. In particular, viewers today might find much to identify with in the boys' predicament: the choices young people being offered for their future don't hardly seem like choices at all.

Henry Jaglom appears in

Drive, He Said as the ringleader of Gabriel's political enclave, and Nicholson returns the favor by taking a supporting role in

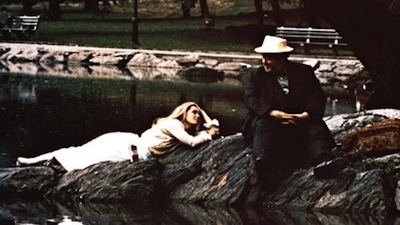

A Safe Place, Jaglom's debut feature as writer and director. The movie is an expansion of a stage play of Jaglom's, though the final product bears little resemblance to a theatrical production.

A Safe Place definitely wears a cinematic wardrobe, though it's a little mixed up as to what articles of clothing go where. The shoes don't always match the shirts.

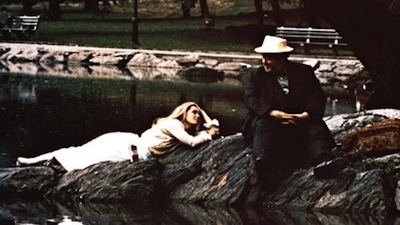

A Safe Place is essentially a romance, working the standard trope of a buttoned-up nerd (Phil Proctor) having a love affair with a flighty female (Tuesday Weld), and never quite figuring out if it is liberating or enraging. The story is told along several different timelines, and much of what we see might just be a fantasy of the girl, who is alternately known as Susan and Noah, depending on what part of the story she is in. Cut into her relationship with Fred are two other relationships: one with an old Magician (Orson Welles), who may be a stand-in for her father if not the real thing, and an ongoing affair with a rich, married man (Nicholson). The Magician seems to understand the girl that Noah used to be--and indeed, is the one who calls her Susan--and also to give value to her dreams. Noah remarks several times that, as a young girl, she could fly, and her main problem with being an adult is she can't remember how.

The true magic of

A Safe Place is in the editing. Jaglom and Pieter Bergema create a kaleidoscopic mis-en-scene, moving back and forth between the various sequences, inserting moments of expressionistic commentary, and essentially pulling off a juggling act that is impressive even if the overall outcome is not. Part of me thinks maybe the script is weak, that some of the tropes are obvious and that the relationship elements and dialogue betray the shallowness of a neophyte writer. In a weird way,

A Safe Place is a bizarre remix of

Breakfast At Tiffany's

, with the girl having multiple identities to cover her past and the poor schlub who meets Holly Golightly even being named Fred. That would make Orson Welles a stand-in for Buddy Ebsen in the Doc Golightly role, and Jack Nicholson as the various rich suitors who give Holly $50 for the powder room.

Regardless of some hinky dialogue, though, the story works, probably in large part because of the fact that it is so familiar. I think the problem ends up being in the acting. The main performers, Weld and Proctor, don't quite seem ready for prime time, with Proctor in particular coming off as if he were in summer stock rehearsals rather than on a real movie set. Weld lacks the charisma to make Noah alluring, she doesn't go deep enough to make us even halfway believe the girl's stories of magic boxes and flying. Both look all the more pale in comparison to their supporting cast. Nicholson is all charm here, working the role quietly, something altogether different than what is generally expected of him. And, oh, what a treat to see Welles at this age! Jaglom brilliantly lets Orson be Orson, magic tricks and all. He has several moments of speaking to the camera, addressing the audience/Noah directly, that show what an arresting presence he could be. It's one of his most comfortable screen performances, where the showiness rarely seems unnecessary or contrived, and instead is just a very real part of a gifted actor's personality.

In one of the documentary features on

America Lost and Found, Jaglom good naturedly points out that though

A Safe Place and Peter Bogdanovich's

The Last Picture Show (1971) were released at the same time, their box office couldn't have been more different. As he puts it,

Picture Show would go on to be the most successful film of the year, while

A Safe Place was the least successful. There is no malice or jealousy in his anecdote. He seems quite clear that Bogdanovich had achieved something special.

For his first major full-length movie, Bogdanovich teamed up with author Larry McMurtry (

Lonesome Dove

) to adapt McMurtry's frank, tersely written ode to small town life in 1950s Texas. Stylistically, Bogdanovich pays homage to the period, using the country music that would have been on the radio at the time as his score, and cinematographer Robert Surtees shot the film in black-and-white, creating instant nostalgia. Nothing else is old fashioned about

The Last Picture Show, however, as it busts the conventional squeaky-clean representations usually associated with the '50s by portraying kids who drink and fool around, adultery, and the general small-mindedness that often came with isolated rural living.

The Last Picture Show is essentially a year in the life of a Texas town, beginning the morning after the last game of the high school football season (it didn't go well) and ending at the start of the next season. Though an ensemble piece, the lead is ostensibly taken by Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms), a thoughtful boy who could be something better than what is expected of him if only he'd take the time to consider it. His best friend is Duane (a young Jeff Bridges), a tougher customer and more of a "free spirit." Duane dates Jacey Farrow (Cybill Shepherd), the prettiest girl in school. Sonny is dating an unpleasant girl at the start, but when they break up, he starts an affair with an older woman (Cloris Leachman), the wife of his basketball coach.

I first saw

The Last Picture Show when I was 18 or 19, and at the time, I pretty much viewed it as a coming-of-age story and little more. Now that I am older, I can sympathize a little more with the older characters and appreciate the fact that Bogdanovich and McMurtry are showing all levels of town life--young, old, and in between. One of the themes of the movie, as with so many of the BBS productions, is the changing times, and unlike most of the other movies,

The Last Picture Show really pays attention to how the turnover effects the previous generations and goes a long way to suggest that the older folks aren't so bad. They have their good apples and their bad apples like anyone else. The obvious focus character is the father figure, Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson), but there are also important lessons imparted by the middle-aged women, played with ferocity by Leachman, Ellen Burstyn, and Eileen Brennan. As good as the young cast here can be, they are schooled by the veterans, who more than own the screen.

Bogdanovich is paying tribute to cinema of days gone by at the same time as he says farewell to and demythologizes the supposedly more innocent past. As a scholar who learned everything he could about old Hollywood, while Bogdanovich took advantage of the looser standards of the 1970s, he still believed in traditional storytelling.

The Last Picture Show adheres more closely to the old ways, employing more conventional techniques than the other BBS films. When he closes down the movie house at the end of the film, it's meant to be the final reel of a bygone era in American motion picture making.

The generational divide is nothing compared to the divide between brothers, if the final film in the set,

The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), is anything to go by. Bob Rafelson returns behind the camera, working from a story he co-wrote with screenwriter Jacob Brackman. Jack Nicholson also teams with the director again, though this time in a role that apparently he almost didn't get. Rafelson didn't think it was showy enough for Jack's talents, while the actor smartly saw it was his chance to be different. Nicholson plays David Staebler, an introspective talk radio DJ sarcastically nicknamed "The Philosopher" by the brother he hasn't seen in two years. When that brother, Jason, calls out of the blue and demands David leave Philadelphia for Atlantic City, David goes, but he knows he's heading for trouble.

Jason is played by Bruce Dern, who at times seems to be channeling some of that trademark agitated energy Nicholson wasn't using this go-around. The pair make for believable brothers--different enough to be distinct, but alike enough that you can believe they came out of the same gene pool. When David gets off his train, Jason is nowhere to be seen. Instead, he is greeted by an aging beauty queen (Ellen Burstyn) and a tardy brass band. Jason, it turns out, is in jail for alleged auto theft. He sends David to get a local business man/mobster named Lewis to bail him out, which is just the beginning of the long con Jason is playing on his brother--though we are never quite sure, even to the end, how much is a con and how sincere Jason really is. If David is the thinker, Jason is the dreamer, and his latest scheme is a resort on a small, uncharted island in Hawaii. He wants his brother to go in with him, and enlists David in beating the bushes for backers, plying him with many promises, including a possible affair with the beauty queen's young stepdaughter, Jessica (Julia Anne Robinson).

It's amazing how easily David falls back into the routine with his brother. The pair of them pull a quick hustle at an auction house just because they can. We already know that David has the gift of gab and a tendency to exaggerate from the opening scene at his radio show, but this is something more. Rafelson is working one of the same irritated nerves that he was picking at in

Five Easy Pieces: how family defines us, good and bad, and how hard it is to discard their influence. In much the same way Nicholson's more outlandish character in that movie gets sucked back into his family's erudite squabbles, so too does his polar opposite in

Marvin Gardens drop right back into the shuck and jive. David and Jason are practically a classic comedy duo: one taller, the other shorter; one outgoing, the other the victim of his partner's over-sized schemes.

Visually, Rafelson and Kovács make use of the depressing aura around Atlantic City in the off-season. It's a gaudy setting, looking a little like the holiday resort version of Miss America without her make-up--an analogy that comes to mind since Atlantic City is where the Miss America pageant has traditionally been held, and in one of

Marvin Gardens' most memorable scenes, the group rents out a hall to perform a mock version of the contest for Jessica. That sequence serves not only to show us the level of delusion that Jason and his ladies operate at, but it's also indicative of how Rafelson and Kovács use the landscape as juxtaposition. The size of the event center overwhelms these tiny people, and the fact that most of the accoutrements are taken down and packed into boxes just adds to how sad and misguided they are. Jason stands tall, but he's at the center of an empty arena.

The ending of

The King of Marvin Gardens serves as a melancholy coda to

America Lost and Found: The BBS Story. As with the movie theatre closing down in

The Last Picture Show, or even Duane and Sonny saying good-bye, the split between the Staebler brothers is an unhappy one. It's necessary, but that doesn't mean they have to like it. They had fun together once. We see it in the final image, their grandfather's home movies of the two boys playing on the beach as children. It's the worst kind of emotional longing: that which can never be again, but that you'll still end up chasing no matter how hard you try to get away from it.

America Lost and Found: The BBS Story is an endlessly intriguing collection. Even if all the movies don't quite hit, they are all interesting, all informative in their way, encapsulating the changing landscape of American cinema and of the country itself. Taken as a whole, they form a kind of anthology, each movie informing the film that would follow, building a larger aesthetic narrative. Of the seven films, three of them--

Easy Rider,

Five Easy Pieces, and

The Last Picture Show--are bonafide classics, and a fourth,

The King of Marvin Gardens, is due to be reevaluated and classified as such. The other three round out the corners, provide the connections between their brethren, and are essential to getting the complete picture of this extraordinary collective. In any creative industry, artists would be lucky to find people to work with as supportive as Bob Rafelson, Bert Schneider, and Steve Blauner. The space they created for their people to work was unlike any other, and it's an experiment that can likely never be repeated--but, boy, wouldn't it be great if someone tried?

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.