Before Belgian director Chantal Akerman redefined experimental feminist cinema with her scathing and insightful Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, the young artist had to undergo a pilgrimage. It was one that required her to travel great distances both physically and artistically. It's this pilgrimage that is examined in the new Eclipse Series 19 boxed set, Chantal Akerman in the Seventies. Five movies on three discs, this collection looks at Akerman's career before and immediately after Jeanne Dielman, and taken all together, they create the image of a developing talent finding her cinematic voice.

DVD 1 of Chantal Akerman in the Seventies falls under the umbrella of "The New York Films." These are three no-budget explorations by a young woman in a strange city. Akerman left Brussels for New York in 1971. She was twenty years old, and though she had begun to make short films at home (one of which, Saute ma ville, can be seen on the Criterion edition of Jeanne Dielman), her new locale and the simultaneous feelings of acceptance and displacement that it inspired opened up a whole new world for her. The three movies represented here, released in 1972 and 1976, are collections of footage she shot around the city during her stay there. Ensconced in the underground film scene, she pushed herself to find new methods of expression.

Leading the set is La chambre (1972; 11 minutes), a short formalistic exercise. Working with her long-term collaborator Babette Mangolte on camera, Akerman stars as herself, the lone figure in a small apartment. The entire film is shot from one position, the camera situated in the center of the lodging, slowly circling the room, capturing the details and the filmmaker in repose with each pass. The only thing that changes is Akerman--who is in bed, sits up, and eats an apple--but as the image goes round and round, it compels you to look, to pay attention to the details and seek out other changes, other tell-tale signs of life. The movie itself is entirely silent (as in no soundtrack, not even a trace of ambient noise), as is its follow-up, Hotel Monterey (1972; 62 minutes). The second movie is a series of images taken at the titular hotel, a rundown building in Manhattan.

Hotel Monterey begins by spying on the lobby, looking at the people coming and going, before moving up the elevator and picking up stationary shots of quiet hallways, a few guests in their rooms, and lonely stairwells. The photography, again by Mangolte, is beautiful and painterly. (The box description compares it to Edward Hopper, and the dark color schemes definitely bring his work to mind.) It didn't really hold my interest, though. I don't have the patience for an exercise of this length. I even put music on in the background to try to keep myself from drifting. (Abel Korzeniowski's score for A Single Man.) I get what Akerman is doing, the way she is manipulating the passage of time in order to create a sense of space, eventually moving beyond the interior and out into the exterior, but Hotel Monterey lost me.

Random footage is put to better use in News From Home (1976; 86 minutes), in which Akerman juxtaposes images of New York with letters her mother wrote to her when she first left home. The director and her camerawoman, alongside additional camera operator Jim Asbell, shoot all over the city, taking in vacant lots, buildings, traffic, and subway crowds alike. We watch as life moves in front of the lens, with people often looking back at us as we stare at them, and the noise of the city quietly bleeds out of the speakers. Intermittently, Akerman shares the letters, reading her mother's passive aggressive missives with a detached tone. There is something unnerving and maddening about hearing this distant woman guilting her daughter to come home while also witnessing Akerman's great love for her new locale. The snippets of news from Belgium emphasize the distance and the longing for the familiar, evoking a sensation of being in two worlds at once.

For her first full-length feature, Akerman embraces the most timid of narrative structures. Je tu il elle (Me You He She) (1975; 86 minutes) is a black-and-white portrait in three acts. Act One, a woman named Julie (played by Chantal Akerman) locks herself in an apartment, where she lazes about, eating from a paper bag full of sugar and writing and rewriting a letter to an unknown lover. Act Two sees her impulsively leave the apartment and head out on the road, where she hitches a ride with a trucker (Niels Arestrup), whom she fixates on but who only shares his abstract philosophy on love after she gives him a hand job. Act Three shows Julie arrive at the apartment of her girlfriend (Claire Wauthion). The two have a romantic dynamic that toys with need and denial: one expresses need, the other denies, then switch. This culminates in fidgety lovemaking, a kind of naked wrestling match.

Akerman is messing around with space and time here, as she did in Hotel Monterey. The shots are long, and they compel us to linger on specific details. This is particularly pronounced in Act Two, where the focus of Benedicte Delesalle's camera is regularly off of Julie and on the trucker's face. She watches him diligently, almost obsessively, and in a scene where the driver shaves his face in a public bathroom, the way we see Julie staring at him with her gaze also reflected in the mirror suggests she is looking as intently as she expects her audience to. In Act One, the director establishes a disconnect between decision and action, effectively recreating Julie's sluggish mind by conveying her thoughts in voiceover first, then showing her acting on those thoughts a few moments after they have passed.

Essentially, the director is exploring her relationships with herself, men, and women, examining how she deals with each. At least how I interpret it, she is expressing uncertainty and frustration with her own ability to be on her own. The sugar is a childish sustenance, the inability to get the letter right suggests complications with self-expression. Men are seen as a convenient way to get along, but they are ultimately more concerned with their own needs, and the way the driver only speaks about his feelings following orgasm makes him seem like an overgrown child confessing to his latest maternal stand-in. On the other hand, Julie is predatory and forceful with her girlfriend. Is this maybe the ex that she has been writing to? Is she as incapable of tenderness as the truck driver? Like him, she only calms when the pleasure is focused exclusively on her.

Like all of Akerman's films, there is no point in Je tu il elle where the author turns around and says, "Okay, this is it and this is what it's all about." Her experiments with framing and shot-length and her unconventional story set-ups are meant to provoke, and sometimes the response is delayed--just as it was for Julie locked in that apartment. Meaning never hits you all at once, particularly in this film, where the three parts are so distinct. It's like an entrée with a trio of individual flavors, all of which stand alone, but once you've scooped them into one big bite, a new, complete flavor reveals itself.

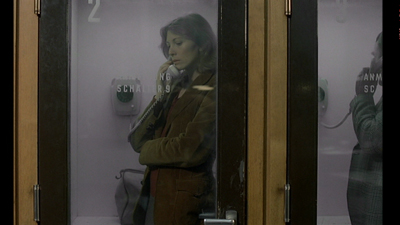

The final film in Chantal Akerman in the Seventies - Eclipse Series 19, Les rendez-vous d'Anna (1978; 126 minutes), was made after Jeanne Dielman and also after News from Home. Both of those films play their part in influencing Les rendez-vous. This semi-autobiographical film follows a successful filmmaker named Anna Silver (Aurore Clement) on a trip to Germany, where she is showing her latest film (Jeanne Dielman?). When she arrives at her hotel, a message from her mother (Lea Massari) is waiting for her. It seems Mom has been trying to get a hold of her daughter for some time, and the communication that we are privy to is very much like the real letters Akerman received from her own mother. "Where are you? What are you doing? Why don't you contact me?"

Like Je tu il elle, Les rendez-vous is structured as a series of encounters. There is the man she meets at her film premiere (Helmut Griem), a sad single father and cuckold; the older family friend (Magali Noël) she meets at a train stop on her way to Brussels; the stranger on the train (Hanns Zischler); and eventually her mother and a former lover (Jean-Pierre Cassel). Anna is another of Akerman's blank canvases, a woman we get to know by the way she reacts to these various people and how they react to her. There is an obvious parable here about how a creative person feels isolated and misunderstood. No one gets Anna as she is, they all want her to fit a role they have for her in their heads. The German one-night stand wants her to fit his romantic ideal, while the old friend speaks to her of marriage and children, encouraging her to accept the norm that is expected of all women. In all these encounters, the other characters are somehow tied into history, both international and personal. Europe, it seems, has made as many bad choices as the individuals seen here have in their love lives. Many of the characters, including Anna, have been displaced. They are looking for life somewhere other than where they are. Even her ex, Daniel, wishes he could abandon everything and disappear--and he's the go-to guy! The safe place to return to is not so safe, not so stable.

There is a formalism to the acting in Les rendez-vous d'Anna that reminds me of Robert Bresson and his theory about actors as "models." The performances are stiff and deliberate, with the actors sometimes visibly spotting their marks and going to them. They speak with little inflection, and stand up straight, positioned with intent. Akerman and cinematographer Jean Penzer frame them in static, straight-ahead shots. If it's a two-person conversation, they stand equidistant from one another, either face to face or looking off into the same direction, the camera remaining locked. For all the movement in their lives, they are stuck in the moment, only Anna keeps going.

The irony for Anna is that the only person she connects to, a female fan she met in Italy, is the one person she can't grasp. While everyone else is trying to hold her, this other woman is constantly beyond her reach. She can never get this lover on the phone, and her journey back to Brussels and then Paris only puts more distance between them. Anna opens up about this to her mother as the two of them share a bed in a hotel near the train station. In a weird way, it's another one-night stand, and it's our one true glimpse at Anna's interior, a confirmation of the loneliness and grief we imagine follows her around. The fact that she asks her mother to get a hotel room rather than going back to their house indicates that Anna is only comfortable with transient things. She can't accept anything permanent, and even when she thinks she knows what she wants, she realizes she doesn't want it once it's available. Thus, she sends away the man in Germany before they have sex, or when she and the family friend, Ida, go in search of food, Anna decides she is not hungry as soon as they step through the restaurant doors.

News from Home ends with an extended shot of leaving New York City. Filmed from the back of a boat, we watch as the traveler gets farther and farther from the shore. It's one move in a journey that began prior to La chambre when Akerman left Brussels for the Big Apple. It's one that is turned to metaphor in Je tu il elle, and that is completed by the cycle of the successful filmmaker Anna passing through various stops in her life in Les rendez-vous d'Anna. The mother's letters receive their response and personal questions about art and sexuality and personal connections are at least broached, if not answered.

When Anna returns to her homebase of Paris, she returns to an old lover, a la Julie. There are also visual echoes of the New York films--shots of Paris passing taken through a taxi window, the empty hallway of Anna's apartment. For the first time in the movie, she reaches out to someone else, attempting to literally nurse her love back to health by taking care of a feverish Daniel. Yet, illness is its own "other state," and he rejects further advances. In the end, she is back home, alone, listening to the disembodied voices on her answering machine, the phantoms that have tried to touch her, but all said and done, she is still nowhere. "Anna, where are you?"

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

No comments:

Post a Comment