Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki is a filmmaker's filmmaker. Long before I had ever seen any of his films--which, admittedly, had been none up until now--I had heard his name bandied about by other directors who admired him. Most notably, he was often referenced by Jim Jarmusch, including the quintessential U.S. indie auteur crafting a segment of his brilliant

Night on Earth as a tribute to Kaurismäki. Watching the movies that make up the boxed set

Aki Kaurismäki's Proletariat Trilogy - Eclipse Series 12, it's easy to see why. Jarmusch has spotted a kindred spirit in this sardonic European creator. His wry stories of regular people quietly floundering through life don't follow regular Hollywood story logic, and his detached filming style gives the impression of behavior observed rather than concocted. As the name the

Proletariat Trilogy suggests, the films in this set, made between 1986 and 1990, focus mainly on working-class heroes, the garbage men and the factory workers who aren't in the mainstream and yet keep it flowing all the same.

Watching the first feature in this collection,

Shadows in Paradise (Varjoja paratiisissa - 1986), I actually started to wonder if the appreciation goes both ways, as there are a few items of business in the film reminiscent of Jarmusch's 1984 breakthrough

Stranger than Paradise. Of course, there is the title, but there is also a forced romance that only really gathers steam on an impromptu road trip, itself precipitated in part by illegal acts. On the way back from it, the female lead Ilona (Kati Outinen) even says her original intention was to run away to Florida, though she had heard there was nothing there but other Finns and "Donald Ducks." Jarmusch's vision of paradise was Florida, as well, and his two male protagonists could pass for Donald Ducks in some circles.

The problem with Florida as a promised land for Ilona is that she has enough of nothing at home, so why go all the way around the world to find more? The sad-eyed blonde caught the eye of the awkward Nikander (Matti Pellonpää) while working as a cashier at the grocery store. Nikander is a garbage man who seemingly dreams of something better. He takes an English course that sounds like it could be for potential hotel managers. His friend at work offers him the chance of a better life by jumping ship and joining the new garbage company he's going to open, but no sooner does the older man say he doesn't want to die driving a garbage truck than he has a heart attack while collecting the morning's trash. Opportunity lost for Nikander.

There is a desperation in Nikander's advances on Ilona that is both sad and comical. He truly doesn't know what to do around her, and their first date is cut short when he takes her out for bingo and comes off as a bore. Yet, when she loses her job and steals the company cash box, Nikander is the only person Ilona can think of to help her out. Before long, she's moved in with him, having nowhere else to go. It's a romance of convenience. Any tenderness that passes between them is at first begrudging. Yet, as time goes on, Ilona does begin to care, and when Nikander finally gets aggressive and starts asserting his feelings, he actually becomes the man she wanted him to be all along. Coming to an agreement on love doesn't immediately transform their lives--as Nikander describes it, using the American idiom, it's "small potatoes"--but yet they manage to find some kind of security in their humble existence.

Portraying characters such as these could so easily become cruel parody, but Kaurismäki is never making fun of his creations, even when he is enjoying a laugh at their expense. Nikander in particular bears the brunt of the director's comic tendencies. Prone to outbursts of macho anger, he's at times tossed into the street and whacked upside the head with a wooden plank, as ineffectual at violence as he is at love. Yet there is something in his grim, silent determination that makes the audience root for the schlub despite it all. Karuismäki does give his lovers a way out, yet one also can't help but think no one will likely even notice they are gone. They themselves are the shadows of paradise, the unseen ghosts that come and go without much impact.

One of the funniest elements of the Kaurismäki style is the deadpan delivery. Outside of Nikander's bursts of anger, there is very little modulation to the emotions in

Shadows. Love and sadness are delivered with the same stony face, the same low manner of speaking. So, too, do the characters in

Ariel (1988) deal with tragedy, romance, and even action and violence--eyes always straight ahead, jaw tight, as if any state of being is just as good as another.

Taisto (Turo Pajala) is another loveable loser, one whose bad luck has taken on the proportions of a cosmic joke. In

Ariel, he loses his job when the hometown coal mine closes, his father commits suicide, and he is hit over the head with a bottle and has his entire savings stolen. And that's just in the first ten minutes! The one thing he has going for him is the convertible his father gave him as his inheritance, but even that doesn't work quite right, as Taisto doesn't know how to put the top down and has to drive through freezing snow sitting out in the open. The Cadillac does get him to the city, however, and in Helsinki he finds work as a day laborer and love after a fashion with a meter maid who is giving him a parking ticket. Irmeli (Susanna Haavisto) is a single mother working multiple jobs to keep afloat. Romance for these two, just like the couple in the previous movie, is more like a convenient arrangement. Taisto says he wouldn't mind spending the night, if it isn't too much trouble, and Irmeli agrees that he might as well come in since it's already dark anyway.

Of course, luck doesn't hold out for Taisto, and when he spots one of his muggers and tries to get his cash back, he ends up in jail himself. In a gesture of simple means but grand meaning, Taisto makes Irmeli a ring in the metal shop where he wiles away the hours and proposes to her on visiting day. There's a subtle irony in that the trapped man sees marriage as a sign of hope, whereas the free man often sees marriage as a trap. Working with his stolid roommate, Mikkonen (Pellonpää again), Taisto plots how to get out of jail and run off with the girl. Thus, midway through,

Ariel becomes a prison break movie, and then a film about fugitives on the run. Mikkonen and Taisto deal with some bad dudes, raise some cash the dishonest way, and plot a course for Mexico. They are laughable as criminals. Taisto drops the money while fleeing a robbery, and Mikkonen's tough-guy act falls apart when his actual lack of fighting skills is revealed, but somehow they manage to get the job done.

The closing shots of

Ariel feature the cruise ship that gives the film its title. It's the means of escape for Taisto and his bride, and it ties

Ariel to

Shadows in Paradise in that that film also ends with its lovers leaving on a cruise ship. There are two different kinds of honeymoons happening here, but the meaning is the same: for Kaurismäki, the only respite from where you are at is to get away from it. Sure, Nikander and Ilona may have to come back one day, and Taisto may run into the law anywhere along the way on his flight from injustice, but there is no chance of happiness if you don't at least try to get out of Dodge. It's the same advice Taisto's father gives him before killing himself, which in itself is another kind of escape. Given the grim determination that gets Taisto out of jail and onto the ocean blue, one might assume that he displays any other emotion sparingly in order to save his energy for when it counts.

As the new family departs, Kaurismäki plays a Finnish-language version of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow." The performance of it sounds somewhat defiant, but also a tad bombastic, making it seem like a tongue-in-cheek choice, suggesting that Taisto's land of Oz is not quite the Technicolor dream of other movies. It fits right in with how Kaurismäki has used music throughout

Ariel, establishing a kind of generation gap by juxtaposing more traditional ballads with American-inspired rock music. The plaintive crooners and the dour lyrics of the old songs underscore the romantic scenes in both

Ariel and

Shadows, exposing them for how anemic they really are, while the rock serves as the soundtrack for fighting back. Taisto and Mikkonen, for instance, blast their radio to distract the prison guard when they are escaping. Radios are also present everywhere in the movie, providing the working class with their one free and easily accessible source of entertainment.

The final film in Kaurismäki's trilogy,

The Match Factory Girl (

Tulitijjutehtaan tyttö - 1990), connects to the others through music, but otherwise breaks from convention in surprising and bold ways. In an early scene, its protagonist, Iris (a returning Kati Outinen), goes out to a dance and the crooner on stage sings a Finnish song about a better land far across the ocean, evoking memories of the endings of the two movies that preceded this one. From its very first scenes, however,

Match Factory Girl is definitely different than what has come before. The black comedy has gotten so black, it's almost imperceptible. Kaurismäki's story of a lonely working-class girl is far more bleak than the other films it is packaged with.

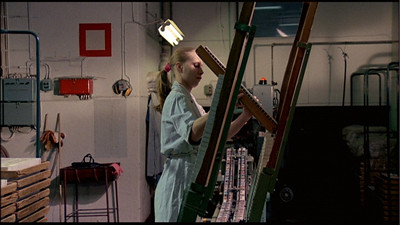

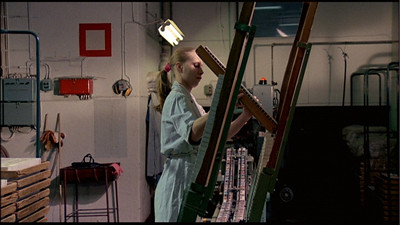

Instead of showing men working with their hands,

Match Factory Girl opens with an extended montage showing the many stages a matchstick goes through on an automated machine. Shot with a kind of visual poetry reminiscent of Louis Malle's automotive-plant documentary

Human, Trop Humain, it creates an immediate disconnect: human hands are no longer involved in the actual production. At least not until the matches are cut, created, and boxed. Iris waits at the end to make sure the labels are affixed to the packaging properly. It's tedious, lonely work.

This isolation continues in her personal life, where she is disassociated from everyone around her. She lives with her mother (Elina Salo) and stepfather (Esko Nikkari), but it's not a loving family--she pays rent and cooks them dinner, and they ignore her by way of thanks. She goes out to that dance, but she sits by the wall, the only girl not invited out onto the floor. Outside of the television newscaster, there isn't even any spoken dialogue in the movie until fourteen minutes in when Iris orders a beer. Even after that, very little is said. Everyone is too caught up in themselves to communicate. The TV news that is constantly running at the apartment serves as commentary to show how small these lives are; the endless reports from Iran and the massacre at Tiananmen Square should tell them that there are bigger things than their inner turmoil, but it seems to pass right by.

Eventually, Iris does meet a man (Vesa Vierikko) who is interested in her, but his cold affections are a far cry from the romance novels Iris reads. Their one night of lovemaking ends for him when he leaves money by the bed (he is at least middle class, if not upper class, and it's a subtle comment on how his type view those "beneath him"), but it doesn't end for her until after she discovers she is pregnant. This brings consequences Iris did not expect, including getting kicked out of her house. Once again, Kaurismäki uses rock music to emphasize change, playing a version of "Brand New Cadillac," complete with the refrain "She ain't ever coming back," to show how Iris' life has irrevocably shifted. It's at this juncture that

Match Factory Girl takes an unexpected twist into the macabre. The scenes of revenge that follow are played with such a poker face, one almost misses the dark comedy that is bubbling underneath. If not for the random action Iris takes in a bar, one might not notice at all how absurd it really is. The music even shifts again at the climax, Kaurismäki returning to his beloved crooners to give the last piece of Iris' plans a faux operatic tone.

Of all of Kaurismäki's steely characters, Iris is the saddest, and Kati Outinen portrays her as always on the brink of tears. The only time she does cry, ironically, is while watching a Marx Bros. movie! The quality of the performance is most apparent, though, in the subtle changes Outinen must show, both in the brief moments of bliss after the night of sex and then the turn Iris takes into contentment when she decides to right the wrongs done to her. In this,

The Match Factory Girl is the most determinist entry of the Proletariat Trilogy: there is no escape outside, there is only the life you can make for yourself.

When it's all said and done,

Aki Kaurismäki's Proletariat Trilogy - Eclipse Series 12 is a quirky tribute to the stoic persistence of the working class in the Baltic states. The odd character of these three films seems to not only reflect the outsider's perspective of their writer and director, but to be part and parcel with the disenfranchisement of its subjects and born of the cultural make-up of where they come from. Imbued with the randomness and often molasses-like pace of real life, Aki Kaurismäki uses film conventions like romance, prison breaks, and revenge plots only to subvert them to his own unique sensibility. There is pity to be found in the dramaturgy, but a gleeful empathy in the dark comedy. Definitely recommended.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.