Given that I write more reviews than what you see here, below is a list of non-Criterion films I covered in the past month that may be of interest to Criterion fans.

IN THEATRES...

* Priceless, a romantic comedy starring Audrey Tautou that has a plot worthy of Preston Sturges, but none of the wit.

* Redbelt, the mildly disappointing mixed martial arts movie from David Mamet.

ON DVD...

* La Chinoise, Jean-Luc Godard agitprop about student protesters and their obsession with Mao.

* The Exquisite Short Films of Kihachiro Kawamoto, seven gorgeous stop-motions cartoons from an innovative Japanese director.

* Le Gai Savoir, Jean-Luc Godard's redefining of 1969 cinema as he knew it.

* Independents: A Guide for the Creative Spirit, an indie documentary about indie comic book creators. Craig Thompson is soooooo dreamy!

* Lost in Beijing, Li Yu's disappointing follow-up to Dam Street, about a love quartet in modern-day China.

* Marvin Gaye - What's Going On/Greatest Hits Live '76: Collectors' Edition, a double-pack bringing together a documentary about the soul singer and one of his mid-period concerts.

* La Roue, a staggering early French silent picture from Abel Gance, telling the literary-tinged tale of a trainyard family.

Saturday, May 31, 2008

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

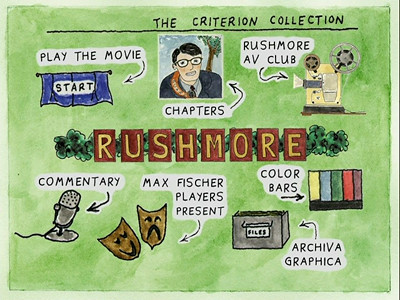

RUSHMORE - #65

Wes Anderson's Rushmore is a beautiful and delicate movie. This may not be evident on the first or even the second viewing (Francois Truffaut says you have to see a movie three times before you should even attempt to write about it), but it's a quality that you've always sensed is there, the X-factor that you can't quite put your finger on but that tells you there is something special about this one, it's not just another teen movie. The genius of the artistry, and the true reason for Rushmore's popularity, is that it manages to entertain even without the viewer actually getting it completely. It's populist art that really is art. Like a great pop song--a confection Wes Anderson appreciates without peer--the basic attraction the movie elicits works on a very obvious level. It's only with time and wisdom that we realize there is more.

My favorite example of that kind of pop song, of course, is the Shirelles' "Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?" (I've used it so often, it's like my comfortable pair of pants.) Listen to it once, and it's a love song about feeling nervous because all your dreams are coming true. Listen to it a few times, let the words (written by Carole King) sink in, and you'll realize that it's actually about a girl ready to surrender her virginity, and she's crossing her fingers that the boy she thinks she loves and whom she hopes loves her won't be gone when the sun rises. Wes Anderson could have easily found a spot for this song on his soundtrack

Anderson didn't necessarily need the Shirelles, as his soundtrack has enough fractured pop songs all on its own. As a director, there are very few that can rival his ear for a music cue (Tarantino and Scorsese, perhaps?). Unit 4 Plus 2's "Concrete and Clay" is just as fragile as "Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?" and its central metaphor is of things that are meant to be solid and eternal shattering into a million pieces. Sure, one ear can hear "Concrete and Clay" and hear a jaunty pop 45 about a love so strong it disintegrates mountains (nature's monument to strength and time) and the cement streets (a man-made foundation, a way to make the world smaller by creating connections) of our cities, things that can stand up to anything that comes their way; listen again with a more cynical ear, though, and ask yourself, if I can't trust the mountains and the roads to last forever, how can I be sure my love won't suffer the same fate? I can dream big, but I don't know that someone else can't dream bigger.

Max Fischer's origin is in very traditional boy's literature. He is Encyclopedia Brown, or for a more cinematic reference, the "Our Gang" mentality of "Hey, kids, let's put on a show." Or, to be more contemporary, Ferris Bueller

Much is made of Wes Anderson's daddy issues. (As Hemingway said, we tell one story over and over, and in each one, we are searching for our father). In his films after Rushmore, the fathers--Royal Tenenbaum, Steve Zissou, the deceased and unseen J.L. Whitman in The Darjeeling Limited

I would actually like to pose that the Bill Murray character, Herman Blume, is not so much a surrogate father figure as a doppelganger to Max. Sure, he may be the type of man Max has always dreamed Bert Fischer could be (and by extension, himself), but again, that dream hits reality, and Blume is more like future Max traveling through time to meet his younger self. Just as much as Max sees Blume as the guy he could one day become, Blume looks at Max as the kid he maybe once was and wishes he could be again. If you think about it, Max inspires a lot of adults to treat him as one of their own--such as Mrs. Calloway (Connie Nielsen), his schoolmate's mother--and also to act like children themselves. His face-offs with Rushmore's principal, Dr. Guggenheim (Brian Cox), brings the good doctor down to Max's level rather than Max rising up to his. Thus, Guggenheim mimicking Max like a playground taunt.

So, too, does Blume act like a child as a result of Max. When he performs as the boy's messenger and talks to their mutual crush, the teacher Miss Cross (Olivia Williams), he doesn't walk away, he runs, like he can't escape fast enough before she sees what is really going on. This also leads to the infamous prank war between the two, with Max unleashing bees in Blume's hotel room and Blume running over the kid's bike with his car (adult tools vs. those of a boy). Miss Cross even says that she dumped Herman because he was a child, and that he and Max are the same.

It's Blume who equates the school Rushmore with Miss Cross, saying "She was my Rushmore." This is the old man lamenting lost love, lamenting lost youth, when a woman could represent everything he desired. When he attended Rushmore, Max was better than the class he was born into, better than society told him he could be. When he had the love of Miss Cross, Blume also feels he's more of a man that what he became. He's not the husband of a wife who strays, the father of boys he doesn't know. Is there any better example of middle-aged angst than Herman Blume, in his pathetic Budweiser swim trunks, leaving his scotch and his cigarette behind on the diving board, jumping into the pool and sinking to the bottom? Even there, he can't escape the nagging world, as the curious and intrusive unnamed child swims by, spying on his pain. Here, too, a perfect music cue: "Nothing In This World Can Stop Me Worryin' Bout That Girl" by the Kinks. Another elegy to perceived perfection and harsh actuality.

I doubt it's a stretch that Wes Anderson sees himself more as Herman Blume than Max Fischer. Max is the kid he probably wanted to be, dreaming of making movies, and if he's like the rest of us, unlike Max, never staging those productions--though Max is a creature of the legitimate theatre. Making Rushmore is that wish fulfillment for Anderson. He gets to put on the shows via Max, hence the recreations of seminal '70s American cinema like Serpico

All coming-of-age tales are, in some way, stories of shedding youthful myths for adult truth. For Max to grow as a person, he needs to accept certain things about himself: that his father is a barber and perfectly okay (and what an amazing acting moment from Murray when he realizes this truth; he says nothing, it's all on his face), he can never have a true love affair with a woman twice his age, and he can never go back to Rushmore. His shift is shown in several ways. For one, he stops taking from Blume and actually helps him. He also stops basing his plays on other people's ideas and writes a story that is all his own, even if the experiences he portrays aren't. (Hey, that's fiction.) The most subtle, though, is also the most telling. After his production of his Vietnam play, in which an overzealous actor cut Max's forehead, Miss Cross notes the wound. He plays it off as being not so much, which is in itself a sign of maturity, but stop and look at where that wound is. It's in the same spot on his forehead that he created the fake injury the last time he tried to seduce her, when Max pretended to be hit by a car. The boy who has pretended to feel deeply no longer has to pretend. The pain is real, and he can deal with it.

One of the best music cues in Rushmore, and one often forgotten due to the song's absence on the soundtrack, is the quiet Rolling Stones number "I Am Waiting,"

"See it come along and

don't know where it's from

Oh, yes, you will find out

Well, it happens all the time

It's censored from our minds

You'll find out

...

Stand up coming years

and escalation fears

Oh, yes, we will find out

Well, like a winter storm

Fears will pierce your bones

You'll find out

Oh we're waiting, oh we're waiting

Oh yeah, oh yeah

Waiting for someone to come out of somewhere."

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

THE THIEF OF BAGDAD - #431

Storytelling is a commodity.

To make a movie is to take a story, confine it in a box--be it rectangle or square--and use it to buy your way into people's lives. It's probably why we get so passionate about the films we love, we've agreed to trade a part of ourselves to make room for them.

In the world created in the 1940 Thief of Bagdad remake, stories are very important. They can be used to save someone's life or to condemn it. The film itself is like a storybook, containing many tales under one cover, some with positive moral lessons and some with truly negative outcomes. The blind man Ahmad (John Justin) uses verse to attract alms and spins a longer yarn about his life as a King to bide his time and buy himself some time in his enemy's home. Within his story, there are other stories, and he is even listening to one when his usurper, Jaffar (Conrad Veidt), catches him unaware. Actually, Jaffar uses a story to set his trap and then uses another to close it. The tale of Ahmad's grandfather traveling out among his subjects to learn more about them is manipulated to convince Ahmad to do the same, and then Jaffar's fib branding the monarch a madman seals his fate. Ironically, in between the two, Ahmad sits down to hear a story about himself and how the toppling of his tyranny has been foretold in prophecy. All these narratives have been his undoing.

The Thief of Bagdad is like a cinematic version of a framed photo of a man holding a framed photo--the very same photo that is in the larger frame. And in that photo, another man and another photo, and on and on. In the movie, the Sultan of Basra (Miles Malleson), a collector of toys, has a replica theatre that contains miniature puppets that perform for him exactly the same way every time he opens the tiny doors. Though, in the movie, these aren't puppets, but real acrobats, and what we see is a miniature film within the film. Like the photo in the photo, the story inside the story, this is a movie in a movie.

Though The Thief of Bagdad is directed by three men, most forget to mention Ludwig Berger and Tim Whelan, and the picture is commonly credited to Michael Powell as director and to producer Alexander Korda as the lord and master. Powell, who would go on from here to begin a long-lasting and joyous collaboration with writer Emeric Pressburger, seemed to have a particular fascination with the fabric of story. In plenty of his other movies, the larger narrative contains smaller ones, be it David Niven accounting for his life on a Stairway to Heaven or the ballet company gripped by personal drama finally putting on their production of The Red Shoes. Thus, making a movie that uses as its source One Thousand and One Nights (a.k.a. Arabian Nights), the granddaddy of all story-within-a-story narratives, makes perfect sense for Powell. It's also notable that it marked his shift from realistic movies like The Edge of the World

In addition to the performers inside the Sultan's toy theatre, there are many instances when one character spies the actions of another through a frame. This works in tandem with the eye motif, which Michael Powell is often credited with introducing into The Thief of Bagdad. It begins with the zoom on the eye painted on the hull of a boat at the start of the picture, and comes up again in both how Jaffar performs his magic and the poetic injustice visited on Ahmad when he is blinded. Multiple times, characters are instructed to look with their eyes or are asked why their eyes are closed. When parted, Ahmad and his Princess (June Duprez) long to look upon one another again, and the difference in worldviews between the twisted Jaffar and the romantic Ahmad is summed up in how they view the object of their desire. The Princess is all Jaffar can see because he can't have her, and though Jaffar insists that when her lover regains his eyesight, Ahmad will see that there are plenty of women all over the world, when the King can see again, he only has eyes for one special lady. Even the little thief Abu (played by Sabu) is told that the key to miracles is seeing the world with the eyes of a child. It's a proper metaphor for the new mythology of moviemaking. The magician uses his eyes to perform his magic, his audience uses theirs to see it. It's a back-and-forth between filmmaker and viewer, here seen as a glorious positive--even if much later in his career Powell would question what we are all looking at in his controversial Peeping Tom.

This eye imagery is probably best represented by the All Seeing Eye, a jewel that Abu steals from a sacred temple, where it has rested for 2000 years. Through this jewel, he is able to find the lost Ahmad, and Ahmad is able to look across the world at his Princess. When the jewel is shattered, it becomes Abu's passage into a realm of miracles. Shattering the eye destroys the collective blindness that afflicts modern society and keeps its denizens from seeing magic. It is also cinema shattering the bonds of centuries of storytelling convention, forging the way for something new and different. You won't just hear or read about carpets flying, you will see them!

Once Ahmad's account of his past--his betrayal by Jaffar, falling in love, Abu being turned into a dog, the Princess falling into a deep trance--catches up with his present, the movie shifts out of campfire mode and remains in the present, moving forward along one line for the duration of the movie. For its second half, Thief of Bagdad becomes everything it was meant to be, its own dazzling story. This is an adventure picture, after all, meant to give moviegoers some thrills and show off the special effects technology being developed at the time. Some of those effects look quaint today, now that we are more familiar with bluescreen and CGI has replaced models and puppets with 3-D constructs. It's not that hard to peer past the veil of fantasy when tiny Abu shares the screen with the giant Djinni (Rex Ingram), yet even jaded viewers should be able to see how playfully this engages the notion of movie illusion. It's almost better that it looks fake, and to get too critical only proves that the All Seeing Eye has ruined our sense of childlike wonder. Why settle for the false nostalgia of billion-dollar retreads of old cartoons and toy lines when you can have the real thing?*

Besides, it's not all bad. The effect of the Sultan riding a horse across the sky still looks pretty good, and one can't help but be awed by the massive, colorful sets and the beautiful matte painting backdrops. This wasn't some cheap production, but an ambitious Technicolor undertaking. The new Criterion transfer of the picture shows every beautiful detail, restoring the bright hues and cleaning up each and every frame. There was probably a time in the past when no one thought movies this old would ever look this good again, but as with so much in The Thief of Bagdad, seeing is believing.

In addition to the new transfer, the Criterion Thief of Bagdad comes with two audio commentaries and a second disc entirely of extras. Of those, a half-hour program about the visual effects featuring special-effects legend Ray Harryhausen unravels the tricks the filmmakers used to create the magic in the movie, including pioneering the bluescreen process (there is a separate demonstration of how bluescreen works) and the employment of miniatures and perspective shots. There is a lot of great footage and photos from the set, though Harryhausen, even as he discusses the techniques, makes a good point about the destruction of illusion in our current need-to-know society. I have long felt that the one downside of the DVD age is that everything is explained to us, we always want to know how it's done rather than marveling at what was done. So, kudos to Mr. Harryhausen.

Alongside this documentary is a feature-length propaganda film from 1940, The Lion Has Wings, which couldn't be further from Thief of Bagdad in tone and subject. This was produced by Alexander Korda and made during a hiatus on Thief of Bagdad. It was partially directed by Michael Powell, and stars Ralph Richardson, Merle Oberon, and June Duprez--though roughly 2/3 of the movie is documentary footage. Even propaganda from the good guys is still propaganda, and so most of The Lion Has Wings comes off as stiffly preachy. The ever-present narration never lets us forget we're supposed to be learning something. The first twenty minutes is a rundown of the build-up to war and what England stands to lose if Hitler were to have his way, and then the rest of the movie is spent with the Royal Air Force. Real combat footage is interwoven with images of the homefront and a dramatization of the flight and ground crew's experience during bombing raids.

It's an interesting curiosity, but not much more than that, and certainly a comedown after The Thief of Bagdad.

* I should note, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull manages to get the nostalgia thing right, and if you're eager to go see it this weekend, I'd recommend following it up with the Thief of Bagdad when it comes out on Tuesday. It will make for a good chaser to quench your swashbuckling thirst.

Labels:

alexander korda,

powell and pressburger,

Sabu

Monday, May 19, 2008

WHITE MANE

Though not part of the Criterion Collection proper, this disc is released through the studio's parent, Janus Films, in conjunction with the main brand.

White Mane is a short children's film by French director Albert Lamorisse (The Red Balloon). Made in 1952, it's an uncomplicated morality play that takes place in the natural fields and marshes in the South of France. Despite having won the Palme d'or for the Best Short at the 1953 Cannes Film Festival and receiving praise from critics as prestigious as Pauline Kael, it's never been readily available in the United States. Unlike the other releases in the Janus Films children's line, I don't even have a vague memory of maybe seeing it at any point as a kid. Which is too bad, since like Paddle to the Sea (which I think I might have seen on TV), I would have found much to identify with in the story. As an adult watching these movies now, it's hard not to get nostalgic for those times, to remember my own past, and insert myself as a boy into the narrative, much like children do when they experience any entertainment.

The horse White Mane is the lead stallion in a herd of wild horses. A local landowner attempts to catch the pure white creature and tame him, but he's too wild and breaks free, returning to the grassy land. This is all witnessed by Folco (Alain Emery), a young boy who fishes in the marshes where he lives with his family. He is intrigued by White Mane, and when the landowner tells him that the horse will belong to anyone who catches him, Folco decides that the someone will be him. Naturally, Folco doesn't have much luck at first, but when he rescues White Mane from one of the traps the horse's hunters lay for him, White Mane accepts the boy as a rider. The herdsmen remain obsessed with White Mane, however, and the landowner appears to be reneging on the promise of ownership, so Folco and White Mane try to outrun the snare of the adult world together.

My dad raised horses all of my life, and when I was in elementary school, I was a pretty accomplished rider. A series of accidents, however, caused me to develop a phobia about horses in my adolescence, rendering me unable to get back on one even to this day. One of the bad memories that haunts me and prevents me from returning to equestrian activities involves my father trying to "break" a young filly. "Break" is the actual term used for teaching a horse to hold a saddle and, by extension, a rider. Up until a certain age, a horse doesn't carry anything on her back, and the natural reflex to having a saddle placed on her back is to toss it off. Get a particularly stubborn horse, and the training process can be protracted and dangerous. For whatever reason, on this particular day, my father decided to make me part of the process. My older sister had helped in the past, but now it was my turn. Until this very moment, writing this now, I had never stopped to think if maybe this was some kind of attempt to "break" me, too, some idea that this would usher me forward toward manhood.

Seeing my dad throw the saddle on this filly, who I think was named Missy, over and over, and seeing her throw it off over and over and, rather than grow more passive or wear down, get more and more frenzied, was really freaking me out. Missy was trying to leap over the corral, she was kicking, her nostrils were flaring, a viscous lather was forming on her thighs--the horse was doing everything she could to keep from being broken. In response, my dad also became more and more frustrated, and it turned into a scary battle of wills between the two of them. I didn't care who won, all I knew was I didn't want to get on that horse. Eventually, Missy ended up tangled in some barbed-wire fencing and cut herself badly above the front legs, the battle of wills halted by physical injury. I'm ashamed to say that I was more relieved to be getting out of the horrible task than I was sympathetic to the horse for having gotten hurt.

I relate this story because the driving event of White Mane is the herdsmen trying to take the horse out of his natural environment and bend his will to their own designs. As a symbol of freedom, a pure white horse has been regularly used by filmmakers as disparate as Andrzej Wajda and David Lynch. A white horse can represent an untouched state, an image of nobility and of how things should be. Though Lamorisse never says anything of the kind, to take White Mane out of his natural habitat is an immoral act, the disruption of the order of things.

Really, Lamorisse doesn't say much at all in this picture, at least not in any explanatory sense. The film is mostly silent, with only the bare minimum of dialogue and narration. (Though the original audio is in French, there is an option for new English narration on the DVD.) If a child is to glean anything from White Mane, it's to come from drinking in the gorgeous black-and-white photography of the untouched French countryside. (In that aspect, this DVD is pristine; the picture is entirely without blemish.) White Mane's film style is practically Neorealist in its preservation of the landscape and even little Folco's rundown shack. The scenes of him and his family--a younger sister, and a man that is maybe a grandfather--are achingly real, their content faces showing no hint of being burdened by the poverty that surrounds them. Though Lamorisse employs sophisticated editing to create a mis en scene that has little in common with pure documentary, White Mane does not contain a hint of falseness. It very well could be a documentary.

And what could a child glean from this? That nature is to be respected, that individuality is to be preserved, and to stand up for what's right need not be a grandiose act, it's something even the smallest of us can do. The herdsman aren't cartoonish villains twisting their moustaches and cackling over their cruelty; rather, they are men who, like my father on that awful day, got such tunnel vision, they failed to see how far their actions had taken them from what's proper and only wake up when it's too late.

It's weird watching White Mane with adult eyes. The movie concludes with the horse and boy heading off into the sunset by swimming across a vast ocean (just like Paddle to the Sea!). According to the narration, they are heading for a land where there is pure harmony, where man and beast are never selfish or mean to one another. If I were still a boy, I would accept at face value that this was some kind of magic, that the land they were heading for did exist and was of some mystical other dimension. As an adult, and as often happens when I am revisiting children's entertainment, I was struck by how grave the imagery really is. The best kid's material always has darker undercurrents. Though if you have children they will likely never consider this, if you watch White Mane on your own, it will be hard not to see Folco and White Mane as swimming toward death. The metaphor is too obvious, and as a metaphor, your reaction to it will likely depend on your own belief in an afterlife, in a world beyond this one, what lies just over the horizon. As with any parable, White Mane shows that actions have both consequences and rewards, and the two are interchangeable depending on where in life you find yourself when you get the message.

White Mane is a short children's film by French director Albert Lamorisse (The Red Balloon). Made in 1952, it's an uncomplicated morality play that takes place in the natural fields and marshes in the South of France. Despite having won the Palme d'or for the Best Short at the 1953 Cannes Film Festival and receiving praise from critics as prestigious as Pauline Kael, it's never been readily available in the United States. Unlike the other releases in the Janus Films children's line, I don't even have a vague memory of maybe seeing it at any point as a kid. Which is too bad, since like Paddle to the Sea (which I think I might have seen on TV), I would have found much to identify with in the story. As an adult watching these movies now, it's hard not to get nostalgic for those times, to remember my own past, and insert myself as a boy into the narrative, much like children do when they experience any entertainment.

The horse White Mane is the lead stallion in a herd of wild horses. A local landowner attempts to catch the pure white creature and tame him, but he's too wild and breaks free, returning to the grassy land. This is all witnessed by Folco (Alain Emery), a young boy who fishes in the marshes where he lives with his family. He is intrigued by White Mane, and when the landowner tells him that the horse will belong to anyone who catches him, Folco decides that the someone will be him. Naturally, Folco doesn't have much luck at first, but when he rescues White Mane from one of the traps the horse's hunters lay for him, White Mane accepts the boy as a rider. The herdsmen remain obsessed with White Mane, however, and the landowner appears to be reneging on the promise of ownership, so Folco and White Mane try to outrun the snare of the adult world together.

My dad raised horses all of my life, and when I was in elementary school, I was a pretty accomplished rider. A series of accidents, however, caused me to develop a phobia about horses in my adolescence, rendering me unable to get back on one even to this day. One of the bad memories that haunts me and prevents me from returning to equestrian activities involves my father trying to "break" a young filly. "Break" is the actual term used for teaching a horse to hold a saddle and, by extension, a rider. Up until a certain age, a horse doesn't carry anything on her back, and the natural reflex to having a saddle placed on her back is to toss it off. Get a particularly stubborn horse, and the training process can be protracted and dangerous. For whatever reason, on this particular day, my father decided to make me part of the process. My older sister had helped in the past, but now it was my turn. Until this very moment, writing this now, I had never stopped to think if maybe this was some kind of attempt to "break" me, too, some idea that this would usher me forward toward manhood.

Seeing my dad throw the saddle on this filly, who I think was named Missy, over and over, and seeing her throw it off over and over and, rather than grow more passive or wear down, get more and more frenzied, was really freaking me out. Missy was trying to leap over the corral, she was kicking, her nostrils were flaring, a viscous lather was forming on her thighs--the horse was doing everything she could to keep from being broken. In response, my dad also became more and more frustrated, and it turned into a scary battle of wills between the two of them. I didn't care who won, all I knew was I didn't want to get on that horse. Eventually, Missy ended up tangled in some barbed-wire fencing and cut herself badly above the front legs, the battle of wills halted by physical injury. I'm ashamed to say that I was more relieved to be getting out of the horrible task than I was sympathetic to the horse for having gotten hurt.

I relate this story because the driving event of White Mane is the herdsmen trying to take the horse out of his natural environment and bend his will to their own designs. As a symbol of freedom, a pure white horse has been regularly used by filmmakers as disparate as Andrzej Wajda and David Lynch. A white horse can represent an untouched state, an image of nobility and of how things should be. Though Lamorisse never says anything of the kind, to take White Mane out of his natural habitat is an immoral act, the disruption of the order of things.

Really, Lamorisse doesn't say much at all in this picture, at least not in any explanatory sense. The film is mostly silent, with only the bare minimum of dialogue and narration. (Though the original audio is in French, there is an option for new English narration on the DVD.) If a child is to glean anything from White Mane, it's to come from drinking in the gorgeous black-and-white photography of the untouched French countryside. (In that aspect, this DVD is pristine; the picture is entirely without blemish.) White Mane's film style is practically Neorealist in its preservation of the landscape and even little Folco's rundown shack. The scenes of him and his family--a younger sister, and a man that is maybe a grandfather--are achingly real, their content faces showing no hint of being burdened by the poverty that surrounds them. Though Lamorisse employs sophisticated editing to create a mis en scene that has little in common with pure documentary, White Mane does not contain a hint of falseness. It very well could be a documentary.

And what could a child glean from this? That nature is to be respected, that individuality is to be preserved, and to stand up for what's right need not be a grandiose act, it's something even the smallest of us can do. The herdsman aren't cartoonish villains twisting their moustaches and cackling over their cruelty; rather, they are men who, like my father on that awful day, got such tunnel vision, they failed to see how far their actions had taken them from what's proper and only wake up when it's too late.

It's weird watching White Mane with adult eyes. The movie concludes with the horse and boy heading off into the sunset by swimming across a vast ocean (just like Paddle to the Sea!). According to the narration, they are heading for a land where there is pure harmony, where man and beast are never selfish or mean to one another. If I were still a boy, I would accept at face value that this was some kind of magic, that the land they were heading for did exist and was of some mystical other dimension. As an adult, and as often happens when I am revisiting children's entertainment, I was struck by how grave the imagery really is. The best kid's material always has darker undercurrents. Though if you have children they will likely never consider this, if you watch White Mane on your own, it will be hard not to see Folco and White Mane as swimming toward death. The metaphor is too obvious, and as a metaphor, your reaction to it will likely depend on your own belief in an afterlife, in a world beyond this one, what lies just over the horizon. As with any parable, White Mane shows that actions have both consequences and rewards, and the two are interchangeable depending on where in life you find yourself when you get the message.

Sunday, May 18, 2008

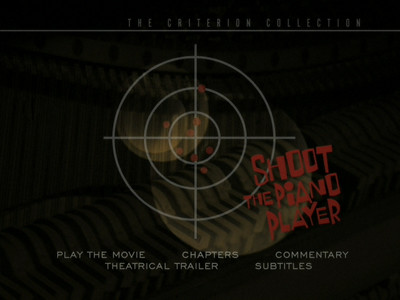

SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER - #315

When discussing the French New Wave, the two names that invariably come up first are Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut. Arguably the most famous of the directors from that very loosely defined school, they also represent divergent artistic approaches that converge in terms of intent even if not always in style. Of the two, I find Truffaut's storytelling style to be cleaner, less irascibly experimental, more concerned with making old formats say new things. Both directors flirted with genre, but whereas Godard stepped inside each style only to dismantle it, Truffaut was more willing to find how his own voice and genre convention could work in tandem. Truffaut worshiped Hitchcock, and the two of them had extended conversations that now serve as a sort of Bible

Truffaut first dabbled in the criminal underworld nearly a decade before, in 1960, when he chose as his second feature to adapt a novel by David Goodis, author of the original story that became the Bogart and Bacall film Dark Passage

Real-life music star Charles Aznavour plays Charlie Koller, nee Edouard Saroyan, a piano player in a dive bar on the Parisian side streets. Charlie is hiding there from his former life, one that comes crashing back when his lug of a brother, Chico (Albert Remy), shows up one night while trying to outrun a couple of hoods. He doesn't understand why his little brother is playing in a bar under a fake name when he could be playing concert halls. This is a question that Charlie would rather not answer; he's put a lot of time into being a man without a past, and he doesn't like being exposed to his nosy boss (Serge Davri), his co-workers, or the joint's regulars. Thankfully, the hoods come busting in before big bro Chico, lumbering around like a Marx Brother that's been fed too much corn and steroids, can completely spill his guts. Even so, the damage is done, questions have been raised.

The tough guys chasing Chico are my two favorite characters in Shoot the Piano Player. Chico first describes them as two men, one wearing a hat and the other wearing a cap, both smoking pipes. And, sure enough, when the pair come strolling into the bar, the description fits. Momo (Claude Mansard) and Ernest (Daniel Boulanger) are talkative and bumbling, coming off more like accidental criminals rather than hardened hoods. They struck me as the wayward cousins of the twin police detectives, Thompson and Thomson, in the Tintin comic books. Though Chico may have eluded them, they now know about Charlie, and they try to muscle him and the waitress who has a crush on him, Lena (Marie Dubois), into giving up the fugitive's location. When that doesn't work, they kidnap the youngest Saroyan boy, Fido (Richard Kanayan), who finds it no more difficult to trick the gangsters than Lena did.

At the center of all of this is Charlie, an atypical noir villain with a typical noir problem. Like the many anti-heroes of the Hollywood films of the 1940s and '50s that comprised the noir filmography, Charlie is trying to bury a past that would be much better forgotten. Unlike the guys regularly played by Burt Lancaster and Robert Mitchum, however, Charlie's misdeeds are not exactly criminal, not in a legal sense. He was happily married to Theresa (Nicole Berger) when fame came a-knocking, and the twin maladies of being hungry for success and cripplingly shy left Charlie little time or energy to pay attention to his wife. His disinterest drove her to drastic measures, and unable to live with the guilt, he gave up everything that made their untenable situation possible. He traded the fame of Edouard Saroyan for the obscurity of Charlie Koller.

Lena actually already knew about Charlie's secret identity. In my review of Malle's The Fire Within, I commented that women were attracted to Alain because they saw a man in need of mothering, and Lena probably has a little of the same attraction to Charlie. He is a wounded bird who needs his heart mended. She is also attracted to his sensitive, artistic temperament, which she thinks makes him different. Charlie fears that he isn't different enough, though, that he is exactly like his brothers, and that he is just a thug and a thief. In a slightly ironic twist, Truffaut reveals that this is not something in the Saroyan blood, there is no genetic predisposition for malice, as Charlie's parents are decent, upstanding people. So why would fate decree that the new generation would be different?

Because fate does have other plans for Charlie, it would seem. His life always goes wrong when he tries for something more than the working-class life that his siblings have settled into. His first bid for musical stardom ended in tragedy, and though when Lena convinces him to return to the concert halls she means to liberate him, fate reaches down and smacks him in the face again, reminding him to be who he is and not get any ideas about being anything more.

This is not a problem for Truffaut, who stretches his creative legs in Shoot the Piano Player and ends up putting together a fun, freewheeling crime picture. Shooting with cinematographer Raoul Coutard, he creates a lovely black-and-white portrait of the Paris underworld, of the juke joints and the late-night streets, the cramped apartments and the grander, open expanse of the city that surrounds them. Traditional modes of exposition are dropped in favor of more playful techniques. Aznavour's voiceover only comes on to express the character's doubts, particularly when he is wondering if he can score with Lena, and when some of the more dastardly news is delivered, it's shown as humorous asides, the action cameoed in the center of the screen. (The title change--the original novel was called Down There--could even be seen as a cinematic pun: shoot him with a camera, shoot him with a gun.) Of the more conventional storytelling aspects, Charlie's past catching up with him and the flashback to his disastrous marriage, the traditional wrapping delivers the most unexpected twist: that Charlie is not the tough customer we assumed of him.

In the end, though, the other conventional element of Shoot the Piano Player is less successful for feeling a little too automatic. The Saroyan family runs a farm outside of the city, and when Momo and Ernest finally catch up with them, the resulting shoot-out comes off as more compulsory than necessary, a required end for a loosely structured movie that hadn't done anyting required of it before this. In a way, this final showdown reminds me some of the seclusion of the similar ending in Godard's Band of Outsiders, and the snowy terrain, gorgeously shot by Coutard, also served Truffaut better all those years later in Mississippi Mermaid. Thematically, the events in this climax do advance the story, however; the consequence of the clash is what forces Charlie to accept his fate. It's almost Promethean in its repetition, and given that the fire Prometheus gave to man could be seen as a metaphor for the creative spirit, it's not too far fetched to tie the piano player's punishment to the greater myth.

Life goes on demanding a price, and Charlie goes on paying it. As Charlie's lost wife told him, "What you did yesterday stays with you today."

ADDENDUM TO SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER AND THE FIRE WITHIN: I usually try to watch bonus features after I've written my review, to try to formulate thoughts and reactions on my own rather than pilfer from others. Tonight, I was finally watching Jusqu'au 23 juillet, an excellent documentary on The Fire Within that compares and discuess Louis Malle's film and the Drieu La Rochelle novel its based upon, and in one portion, actor Mathieu Amalric (The Diving Bell and the Butterfly) is talking about how Alain is noticing the vast details of life, searching through the minutiae for a reason to have some hope. He mentions Alain looking through his window at a girl walking in the street with a violin. When they cut to the scene, the girl made me think of a similar young lady in Shoot the Piano Player, a musician who has just finished auditioning for the man who will become Charlie's agent. She walks out listening to him play, carrying her own instrument. They could almost be the same girl, she could be leaving Charlie and walking home, passing by Alain.

Also, in another clip, we see a copy of Babylon Revisited & Other Stories by F. Scott Fitzgerald sitting at the front of a stack of books in Alain's room. A detail I completely missed on my own! I guess I was on to something!

Monday, May 12, 2008

THE FIRE WITHIN - #430

"Life flows too slowly in me. Tomorrow I kill myself."

The Fire Within, Louis Malle's 1963 mediation on the Pierre Drieu La Rochelle novel Le feu follet, is surely a polarizing piece of cinema. The above line, spoken by Maurice Ronet in the role of Alain Leroy, recovering alcoholic and depressed lout, isn't a metaphorical come-on. He really means it, and The Fire Within is 108 minutes of watching Alain prepare for his suicide.

Suicide is still one of those subjects that authors and filmmakers tend to be shy about. More often than not, when the topic is examined, it's either from the point of view of someone avoiding it or more likely about the fall-out the suicide leaves behind and the effect the death has on his or her loved ones. It's always been odd to me that there aren't more fictional endeavors that seek to understand the point of view of the suicide himself (I hesitate to call anyone a suicide "victim;" you certainly couldn't do so for Alain in this movie). In a day and age when a serial killer can be the protagonist of a TV show, a person taking his own life is still taboo, still not talked about. Some fear that maybe such a film will romanticize the idea and make the choice seem attractive; others may just fear to entertain the possibility because they fear what they will see at that edge of life, or they are so set in their ways about it being wrong or cowardly or what have you, they don't even bother to look at the grayer nuances of the morality.

Again, any of those fears could just as easily be applied to a sociopathic killer. You might make murder look cool, you might have to accept your own violent fantasies, and Jesus, yes, murder is wrong!

Louis Malle disproves all of those concerns in The Fire Within, and he does so by not addressing them at all. There is nothing romantic about Alain Leroy's final days, and whether Malle answers any questions about himself within the narrative is an item he keeps to himself (though, we do know that he lived a happy and productive life long after completing the movie, dying from lymphoma in 1995 at the age of 63; so, clearly making this picture didn't push him over the edge). Questions of right and wrong don't even come into play. Alain has made his decision, and the camera merely follows him on his way.

"The thing is, I can't reach out with my hands. I can't touch things. And when I do touch things, I feel nothing."

When we meet Alain, he is on his first outing following four months of intensive detox at a clinic in Versailles. Alain, as we will learn, was once the life of the party, a pretty boy who has destroyed his looks and his nerves through an excess of alcohol. The ladies loved him, and as we'll see over the course of the movie, often more out of a desire to take care of the lost little boy than anything sexual. As it is, Alain is currently on a date of sorts with Lydia (Lena Skerla), a woman who is not his wife. Alain left his wife, Dorothy, back in New York, where apparently his demons got the better of him. Dorothy has ended all contact with her husband, and despite whatever horrible things Alain did to cause this, Lydia still encourages him to run away with her. Alain has other plans.

Malle smartly keeps Alain's past sketchy. If Dorothy can't forgive him, we might not be able to either if we knew what he had done to earn her disdain. We only learn more about Alain's past as he encounters people who were a part of it. Some are oblivious to the changes in him, only remembering what a wild man he once was; others cautiously believe that he will return to his former self; while still more pity a man who is a mere shell of his youthful Bacchanalian image. Alain falls mostly in the latter category. He holds no pride in his past, seeing it as a string of failed connections. He has no one, and that makes him no one. (As Morrissey would say, "I enter nothing, and nothing enters me.") He wanders through Paris, seeking to make peace with his friends on the eve of his final deed, like a hero in an F. Scott Fitzgerald story. Charlie Wales in "Babylon Revisted," visits his old friends because he wants to prove he has changed; unlike Charlie, Alain has accepted that he has not. Maybe he has found some clarity, but once the cloud of booze has been lifted, there is not much remaining that's worth liking.

A perpetual gray hangs over The Fire Within, like Alain is stuck at the moment when the sun has just begun to set. The only atmospheric changes to come are rain and the skies growing even darker. For a lot of the picture, particularly when outside or in the larger apartment of Alain's friends the Lavauds (Jacques Sereys and Alexandra Stewart), Malle and cinematographer Ghislain Cloquet keep a respectable distance, shooting Alain with a preservative pallor. He walks through Paris like it's a museum, pausing next to statues, visiting his old haunts like exhibits of a distant artistic period. Here is the bar where I had my morning pick-me-ups, and over here the apartment where my former drinking buddy has settled into a life of family and letters. On the other side, you will find my friends the radical political activists, still pursuing the lost cause the way my poet pals still pursue medicated oblivion.

In some fashion or other, Alain tells all of these people that he is going to kill himself, something we know those contemplating suicide will do. For the most part, they choose to ignore it, thinking their friend is being dramatic and will snap out of it. Only Jeanne (Jeanne Moreau), who lives amongst the decadent poets, seems to take it at face value, accepting her own helplessness with regret when she lets Alain get away. These reactions serve to establish that otherness that Alain talks about. Conversation proves his separateness from other people, the camera shows he is one step removed from his surroundings. Even his confining room in the clinic appears larger than him, the clutter of his life arranged in an attempt to mimic the clutter of the outside world, but serving more like a mausoleum. Or, again, like a museum--a place where the defunct is entombed for posterity. The photos of Lydia and Dorothy, a brunette and a blonde, the attainable and the irretrievable, that Alain keeps on his mirror are no substitute for the real thing.

The Fire Within is a sad movie, but it's also engrossing in a way that is almost counterintuitive. I found myself worrying more that Alain might fall off the wagon and take a drink than I was if he would carry through with the suicide. In fact, if I'm being honest, what worried me about that was that if he got too drunk, he might not carry it through. If Alain were to go on a bender, he could get stuck in the same cycle and never get out. I suppose I could have been wishing for a parable out of the Albert Camus school of thought, using the writer's concept of the plight of 20th-century man, which has so fascinated me and been a part of my own work, the idea that by accepting the need to kill oneself, a metaphysical death occurs that makes the physical one redundant. Yet, again, there is not a lot of philosophy here. Alain discusses a variety of ideas about the forward momentum of existence with his buddy Dubourg (Bernard Noel), the armchair Egyptologist, but Alain has already reached that Camus state. The larger questions no longer concern him.

"I leave you with an indelible stain."

It would be silly to think, though, that Malle is able to avoid all moral questions in regard to Alain's decision simply by not bringing them up. Every viewer enters into The Fire Within with his or her own set of morality, and while ideally any story can take us out of our own safe world and teach us a little something about what others experience, in the end we still can only measure what goes on in that story against what we already know or believe. In my case, for instance, I found myself differing from Alain when Malle reveals what words his subject intends to leave behind. Alain only composes his note on the day he is to commit the act (July 23, the date written across his mirror), after indulging in a morning comprised of the purely mundane. He packs up his things, finishes the book he has been reading, and takes down his photographs.

In this tidying up of his own mess, Alain brings to mind the character of Robert Frobisher in David Mitchell's Cloud Atlas

The suicide note is telling. Whereas Frobisher wants his death to reverberate as little as possible across the lives of others, Alain reveals that his decision isn't just about personal release, but a final act of revenge. He wants to get back at Dorothy, and in a grander way, all of womankind, which he has seen as abandoning him. His death would be the "indelible stain," and though he would be finished with the pain, Dorothy will have to live with the lingering after-effects. Was I blind to this meanness in his previous poetic musings, or is this the first time that he has truly been honest? That is the final question I was left asking myself as The Fire Within concluded, drifting off quietly with no announcement, a black screen, not even a "Fin" title card. In a weird way, the final frozen image of Alain echoes the last shot of Antoine Doinel in Truffaut's The 400 Blows. On one hand, it says everything we expect it to say, and on the other, it hints at deeper ambiguity. Is it hopeful? Will they get everything they wanted? Or have the trials only just begun?

Having had the time to think about it, I realize that it's this last turn that makes The Fire Within truly special. It's one thing to track Alain's decline, to let the pieces fall where they may and simply present us with a glimpse at a rarely examined state of being--that would have been something unique and glorious on its own--but it's a whole other to stop us in our tracks and ask us if we really have it all figured out, if what we have seen is limited to what appears on the surface of it.

It's a daring move. It takes The Fire Within from a portrait that seemingly avoids editorializing to one that reveals that everything has an editorial slant. If we got back to the reasons filmmakers and writers might be scared to tackle the suicide question, it could be that they don't want to risk getting caught in the quagmire of something that can only bring more questions that have no answers. At least not ones that can be found without going over to the other side--and once we do, we can never come back to share, we only become another query.

BLOG BUSINESS: I apologize to my readers for not updating last week. I would like to pretend it was on purpose in order to keep that cute picture of Jeanne Moreau riding high on top of the blog, but that just isn't true. Various comic book events over the last three weeks meant a lot of increased activity and almost all of my reviewing ground to a halt. I will be attempting to post at least two more reviews here in the next two weeks in order to catch up.

Thursday, May 1, 2008

THE LOVERS - #429

Louis Malle's 1958 film The Lovers (Les amants) is an erudite reimagining of a traditional bodice ripper. Jeanne Moreau, who had made her name with the young director in Elevator to the Gallows, plays Jeanne Tournier, a bourgeois housewife stuck in a passionless marriage with a rich newspaper editor, Henri (Alain Cuny). Seeking refuge from this dismal union, she regularly travels from their country home to Paris under the cover of visiting her best friend Maggy (Judith Magre), but really to hook up with her lover. Raoul (Jose Luis de Villalonga, the Brazilian moneyman in Breakfast at Tiffany's

Jeanne's disaffection not only shows on screen, but also surfaces in a third person narration that Malle cunningly chooses Moreau to read. It has a disassociative effect, that the woman is both in the moment and out of it, commenting on her own existence as a pitying other. Perhaps sensing his wife's ennui, as well as maybe picking up signals regarding her true relationship to Raoul, Henri starts insisting that Jeanne spend more time at home. He even cancels his own plans so that he can spend the weekend with his wife, asking her to invite Maggy and Raoul to their home rather than allowing her to spend the time away. She still insists on an overnight trip to Paris, ostensibly to lay the groundwork for this impossible situation, but also presumably as one last hurrah in case it all falls apart.

It's hard to tell what Henri really knows. Once everyone is at the Tournier home, it's fairly obvious to the outside viewer that Jeanne is incapable of hiding her unease of having her lover and her husband in the same place. Henri seems to see it, but he doesn't show it. He pours on the charm, but his motives are unclear. As it turns out, he's watching the wrong man, anyway. Neither he nor Raoul suspects that Bernard (Jean-Marc Bory), the learned drifter that has escorted their woman home, is going to be the downfall of them both. He's a man who, though born into their level of the social hierarchy, has dropped out in favor of what he sees as a more liberated existence, and he has a contempt for the way all of them conduct themselves.

Malle appears to take great delight in playing with the conventions of seedy romantic tales, turning rather conventional situations into visual and literary metaphors. When Bernard first meets Jeanne, she is literally stranded, her car having broken down on the side of the road, next to a river, equidistant between her lover in Paris and her husband at home in Dijon. He rescues her first from that predicament, and then from her stalled sex life. While Raoul and Henri represent society and industry, Bernard is nature and instinct. His ruggedness makes Raoul's safely structured athletic career seem ridiculously wimpy. Jeanne and her people have tried to sequester themselves from the natural world, seeing it as a quaint thing to visit but otherwise as an impediment to their consumption of fashion, gossip, and the other accoutrements of a material life. Bernard's appearance is like an infestation. At dinner, a bat flies in through the window; later, a fly buzzes around Jeanne's head, irritating her, yet pushing her outside, where she meets Bernard for their first, albeit unplanned, rendezvous.

The night forest is photographed in chilly grays, lit to appear almost otherworldly, Jeanne standing out from the background in stark relief thanks to her angelic white nightgown. Bernard is not content to make Henri a mere cuckold, but he mocks the husband, as well. Before he even meets the man, he characterizes him as a bear, but not a force of savagery, one who is more domesticated, like a circus performer. Leading Jeanne through the woods, he happens upon a fish trap that Henri has set in the river, and Bernard sets all his capture free. He then takes Jeanne onto a small boat on the selfsame river--likely also the one she was stranded by only that afternoon--and the two new lovers float adrift on its waves, surrendering to the natural flow. Though earlier in the film Maggy thinks she can see a change in her friend thanks to her love of Raoul, Bernard awakens something more primal in her. When they return to the house, the dogs stir, barking at the newly sensual beasts that approach.

1950s audiences must have been as scandalized as the dogs when they saw the scenes that followed. Bernard ravages Jeanne in her bedroom. She wears nothing but a pearl necklace (yes, I know!), and Malle shows her writhing in ecstasy after Bernard has disappeared off the bottom of the screen. Yet, here amidst the breathless, orgasmic exclamations, Malle is already starting to turn our preconception of romance stories on its ear. Though our inclination is to root for Jeanne's liberation, it's difficult not to question her moral choices. On the way to her bed, the two adulterers pass through her daughter's bedroom, and Jeanne checks on the girl, the tuck-in serving as a good-bye of sorts to her old life. My eyebrow certainly rose when Bernard almost immediately turns the girl's existence into a part of his seduction, declaring that he not only loves Jeanne, but her daughter, as well. Men truly will say anything to get a woman into bed!

That crass come-on resonates well into the next scene, particularly when Jeanne makes silly declarations about the eternal value of their very young love. While we know her quality of life has not been ideal, Malle has had his topsy-turvy way with our perceptions from the moment the drama settled at the Dijon estate. Raoul reveals himself to be a bit of a bore, and Henri is uncharacteristically doting, and though Jeanne and the audience both suspect that it's fueled by his own suspicions, it causes us to doubt if he is as bad as we thought. Then again, maybe it's not uncharacteristic, since a concerned maid has told us that the father spoils his child, so maybe Malle has made us too trusting in Jeanne's interpretation of things. The writer/director has already fooled us in this way once, making us think that Henri was also engaging in infidelity before revealing that his mistress is his work, exactly as he said it was.

Certainly we are ill prepared for Jeanne, a wife and a mother, to abandon it all to run off with this wanderer whom she has just met. Even his decision to carry her away is somewhat ironic, given that when they first met, he refused to hurry her home, claiming he never resorted to speeding in his car because he didn't believe in going too fast. Their flight is meant to be romantic, but something isn’t right. Bernard insists she bring no possessions, and though it's meant as a gesture to their new life where they need only each other, given his previous political statements, it comes off more possessive of him. If she has nothing but him, she can rely only on him. Plus, he is making her come to him on his terms, sacrificing all for his sake.

Post-coital guilt rises with the sun. Even as they flee the estate, the bliss of their night of passion starts to go sour. Mirrors reflect their guilt back at them by showing them their own haggard appearances--he is unshaven, her sleepless night has created bags under her eyes that her lack of make-up leaves uncovered. She can barely stand to be looked at. Bernard says that he wishes it could always be night, and almost immediately after, a rooster crows three times. It's a Biblical number, making me think of Peter denying Christ three times before the cock crowed. It's just the quantities here have been swapped.

The final images of the lovers together, along with the last telling lines of narration, are also reminiscent of Mike Nichols' The Graduate. Though all the words spoken and everything we know tell us this must be a happy occasion, love conquers all, the expressions on the faces of the pair doing the loving suggests something else entirely. Real life waits over the horizon. The idyll only existed in darkness.

The Lovers is one of those movies I have been anxiously awaiting on DVD. I first saw it at a retrospective of Louis Malle films a couple of years ago. It was actually the only installment of the series I attended, and more for Jeanne Moreau than Malle. I can't recall whether I had seen this movie before or after I saw Moreau in Tony Richardson's similar 1966 film Mademoiselle

Which isn't mean to suggest that the sexiness of The Lovers is somehow false, because nothing could be further from the truth. It's a story tantalizingly told, panting with the salaciousness of Hollywood "women's pictures" by the likes of John M. Stahl or the female-centric noirs of Otto Preminger. It's just that for as sexy as the movie is, Louis Malle is aware of the consequences of surrendering too much to raw emotion and never stopping to ask yourself what will be waiting behind the lust when it eventually clears.

The box boasts that this is the original, uncensored version of the film. I don't know exactly what was censored before, though it was most assuredly in the orgasmic love scene, which includes a very brief glimpse of female nudity. The film infamously was embroiled in an obscenity case in the U.S. when it was shown in Ohio, so I am sure it was trimmed for subsequent theatrical showings to avoid any further litigation, despite the original ruling against the film being overturned by the Supreme Court. In fact, it was The Lovers that apparently inspired the still-in-use loose definition of obscenity: "I know it when I see it."

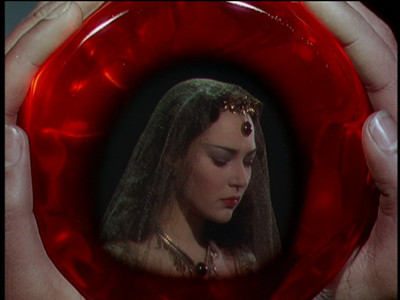

The Lovers - Criterion Collection is packaged in a clear plastic case with printing on all sides of the cover. I like that the same image that appears on the disc itself also appears underneath, though the circular red swirl that goes around Jeanne Moreau on the surface of the DVD has a nice vertigo effect, evoking the spiral of passion her character will find herself in. The accompanying 14-page booklet has cast, crew, and chapter listings, along with photographs and a critical history of The Lovers by film professor Ginette Vincendeau.

For technical specs and special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

This DVD set will be released on May 13, 2008.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)