Throughout Jacques Tati's 1971 comedy Trafic, we get multiple updates regarding a rocket ship to the moon. It begins with the lift-off, when Tati's Monsieur Hulot and his driver are stopped at a mechanic's looking for help, and ends with the astronauts walking on the surface of the moon while they are at yet another mechanic further down the line. In that scene, the wrench-man Tony (Tony Knepper) and the truck driver Marcel (Marcel Franval) re-enact the spacewalk by moving in exaggerated slow motion around the auto shop. Hulot, frustrated by the slow progress that this goofing represents, gets angry, the final punctuation of an understated visual gag that connects many of the episodes in the film. Seeing the rocket blasting off as Hulot's land-based journey comes to a halt, Tati is casually playing with the cliché, "We can send a man to the moon, but we can't...[fill in the blank]."

In the case of Trafic, the blank would be "but we can't drive from Paris to Amsterdam." For this later Hulot feature, Tati has put his raincoat-wearing, pipe-smoking comic figure into a situation full of delicious irony: the seemingly impossible trek to an auto show in Amsterdam so that Hulot, now a car designer, and his company, Altra, can show off their latest vehicle. You'd think that one thing that folks in the business of building transportation devices could accomplish would be transporting their new model to where it needs to go. Ah, but no such luck! Engine trouble and blown tires, traffic jams, law enforcement, and multi-car pile-ups all await them, and not once does Hulot, Marcel, or the hyperactive press agent Maria (Maria Kimberly) ever consider that if the truck can't go the distance, they could just pull the car out of the back and drive it.

Jacques Tati has always been fascinated by the confluence of human ingenuity and modern living. Noting that machines rely on humans to keep them running as much as humans need their machines, he sees that both are dependent on and subject to human foibles. In Mon Oncle (1958), the writer/director/star sent Hulot to a fully automated house where he was delighted and confounded in equal measure by the endless array of modern conveniences, whereas in the monumental Playtime, (1967), he showed us how an entire city could work together as one amazing symphony. For Trafic, he reconstructs the ballet of highway travel.

Tati's films are mostly free of dialogue, with the focus instead being on the movements and the sounds of industrial life. The squeak of a windshield wiper can say as much as a verbal joke, and in a Tati film, he may even wring more laughs out of a situation by cutting through the need for vocabulary and getting right to the funny. In fact, there is a gag about windshield wipers in Trafic, coming near the end of the picture when the skies open up on one final congested road. Tati moves in to see a pair of women talking in their car, the back-and-forth of the wipers matching their wild gesticulations and the sound of rubber on glass standing in for whatever inane chatter they are engaged in. It's a perfect Tati moment, humans and machines working in concert. It's representative of his overall approach. Throughout the film, the director gives equal time to the technology and to the people who use it. He is just as likely to linger on an interesting face as he is a finely crafted piece of metal. One always needs the other to make Trafic work.

The windshield wiper incident isn't the only time the two things crossover, either. Earlier in the movie, gawking men on the street are seemingly admiring Maria's roadster, its structure and its accessories, only for us to realize that they are talking about the hot rod's hot driver when another attractive woman has crossed her path. In this case, Tati breaks form a little, creating a gag that uses technical jargon to show us how we are becoming one with our toys: men talk about women the same way they talk about cars. Within that gag is an added gag, a visual countermeasure that works in tandem with the leering fellows. We see in detail how Maria uses her car as a kind of fashion accessory, a mobile closet, stashing her clothes in various compartments, including her hat in the wheel well with the spare tire.

There are other wonderful moments of choreography in Trafic. Sometimes it works for the characters, such as the synchronized motorcycle cops who pull Hulot and Marcel over, and sometimes it all goes south, like when the distracted traffic conductor accidentally instructs all four directions to go at once, causing a hilarious pile-up worthy of an episode of "CHiPs." The sight gags in that sequence alone make the movie worth it, including a very pointed joke about a priest servicing his VW Bug as if it were an altar to be prayed at. Our cars have even become our religion!

The true marvel of construction, though, is the car Hulot is looking to premiere at the auto show. Stopped by customs crossing the border from Belgium to Holland, the guys are forced to display their wares to the curious customs officials. As it turns out, the automobile Hulot has concocted is a camping vehicle, full of all the conveniences campers may need, from a pullout tent in the back to a front grill that converts to a barbeque grill. There are even blow-up mattresses in the bed of the car (oh, these puns!), an electric shaver in the horn, and a shower. It's like the house from Mon Oncle squished and mounted on four wheels. It also explains the fake forest Hulot's advance team constructs at the car show, complete with a big log that the single car that made it to Amsterdam drove in on its roof. It's another visual joke from Tati, this recreation of nature in the most unreal of places being a sign of our age. (Anyone doubting the size and spectacle of the auto show should revisit Louis Malle's auto industry documentary Humain, Trop Humain, which features footage of a similar convention; Tati did not need to exaggerate for comedy. Hell, the title could even be applied to Tati's oeuvre in the same ironic way Malle uses it. "Human, all too human.")

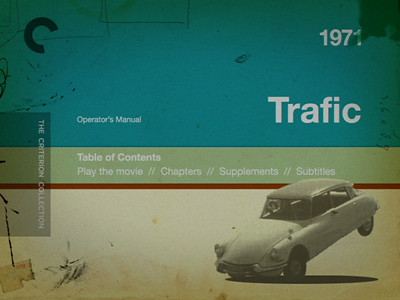

Fittingly, Trafic ends up not in this fake environment, but in a real lakeside hideaway. The last mechanic, Tony, is off the main road and by the water, and his refusal to work in the dead of night serves as Tati's admonition to all of us. Settle down, enjoy yourself, admire nature, because whatever you are rushing to will be there later. You may miss the big event, but so what? People will still buy your widgets, and at least you enjoyed yourself in the process. Thus, the meticulously constructed film (man, even the poster was a masterpiece of design! [see below]), ends on the simplest of notes: two people walking in the rain, leaving the vehicles they arrived in far behind.

No comments:

Post a Comment