As a fan of early-20th Century American literature, I always noticed that the one group of writers that could inspire real envy in all of the famous Americans was the Russians. Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and the like are regularly mentioned by Hemingway and Fitzgerald and their crew as the authors they most looked to in terms of what they wished they could do, the level of craft they aspired to achieve. For a long time, I didn't understand why, because like many young readers, I was a little frightened by the prospect of reading these legendarily long tomes. Charles Dickens wrote books that fat, and I didn't much care for him, so what chance did these Ruskies have?

Then a couple of years ago I finally read Tolstoy's

Anna Karenina

, and that changed everything. While I can't claim to have gobbled up a ton more since then, the densely plotted yet deftly told

Anna Karenina made me realize what inspired the men who inspired me. The writing is detailed yet lyrical, the story complicated but has enough soap opera to keep it from being boring, and the characters are so richly drawn, you feel like you get to know each and every one, no matter how insignificant. Having experienced Tolstoy, it helped me understand what Steinbeck and Fitzgerald were trying to do when they wrote the mammoth

East of Eden

and

Tender is the Night

(respectively), both books I read (and in the case of Fitzgerald, reread) in my post-

Anna K. world.

Funny that I should be scared of a big novel, though, as I've never been scared of big cinema. Granted, watching a movie takes place in a set amount of time, and at my reading speed, I've had books drag on for upwards of a year for me. Still, I've spent weekends devouring the whole

Godfather set or a complete season of

The Wire

, an entire evening in an uncomfortable theatre watching

The Best of Youth

, so why not some time flipping through the pages of

War and Peace

? When it comes down to it, such substantial artistic experiences are rare. How often do we really get to see or read a truly brilliant work of such incredible density?

Berlin Alexanderplatz looked like an insurmountable expedition when I cracked open the box, but I had watched all fifteen hours within two or three days and never checked the clock out of boredom. Shouldn't, then, Proust be on my nightstand?

Masaki Kobayashi's nine-and-a-half-hour film

The Human Condition was released as three parts over three years, spanning 1959 to 1961. On this new Criterion edition of the landmark film, the three-part structure is preserved over three discs, and it includes the original intermission breaks in each part. So, really,

The Human Condition is like a six-chapter novel, the equivalent of six ninety-minute television episodes. Not so daunting when you think about it that way, is it? Not that you'll likely stop at any particular break. Just like reading a good book, I watched

The Human Condition into the wee hours, dropping out and going to bed when I just couldn't keep my eyes open anymore, then picking it up where I left off the next day.

Now, even if watching

The Human Condition isn't a daunting task,

reviewing it is (I know, and get on with it already, right?). To adequately cover the full girth of this particular piece of cinema would practically require a book unto itself. The reason a movie like Kobayashi's is so engrossing is that, like a Russian novel, it is full of recurring themes, side characters with their own lives, and a story that maneuvers through territory as wide as any map--and likely territory that was also covered in the Gomikawa Junpei novel upon which

The Human Condition was based. When it comes to a movie of such magnitude, whatever you write in a space like this, it's like using measuring spoons full of water to show someone what the ocean is like. I need flowcharts and character graphs just to keep it all straight!

But here, I'll try...

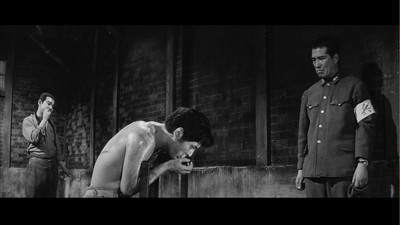

The Human Condition opens in Manchuria in 1943. Japan is in the middle of World War II and using their occupation of China and the country's natural resources as fuel for the war effort. Kaji, played by Tatsuya Nakadai, is twenty-eight years old and full of ideas. He believes that improving working conditions for the common man will improve production output, and even thinks the Chinese forced into labor are entitled to be treated as human beings. Not surprisingly, some consider Kaji to be a radical. His theories sound vaguely Communist.

Like any young man, Kaji is also interested in romance, and he has been dating Michiko (Michiyo Aratama), who works in the same compound with him. She is ready to get married, he is not, as he fears that any day he could be drafted into the Japanese army. A reprieve comes, however, when he is assigned a position at a remote mine where Kaji can employ some of his crazy notions in the aid of extracting precious metals from the Earth. This important work will buy him an exemption from military service. Eager to do some good, Kaji marries Michiko and the two move to the desolate mining town. There, he befriends the tough but fair foreman Okishima (So Yamamura), but quickly makes enemies of the other bosses, who thrive on bribes and sadistic motivational techniques.

Kaji eventually succeeds, but not without much effort and little praise. Things get more difficult when the army drops off 600 Chinese prisoners and puts Kaji in charge of them. When his enemies help several prisoners escape in order to line their own pockets, Kaji not only loses the trust of the POWs but also runs afoul of a macho military police officer, Sergeant Watai (Toru Abe), who ceases to be amused by Kaji's tactics. Convinced that Kaji has been turning a blind eye to the escapes, particularly once it's revealed that a Chinese boy (Akira Ishihama) that Kaji has taken under his wing has been part of the plot, Watai puts the screws to our hero. Having already been forced to compromise his ideals to the detriment of his self-esteem and his marriage, and often at the cost of lives, Kaji decides to take a stand. His reward? Conscription into the army.

End of Part I, often subtitled

No Greater Love; part II is

Road To Eternity, and it opens with Kaji on the tail end of his basic training. He and one other solider, the disagreeable Shinjo (Kei Sato), are both outcasts due to their perceived Communist-sympathies, but Kaji in particular has distinguished himself as a sharpshooter. He has also tried to be an ally to the nerdy, pathetic Obara (Kunie Tanaka), who clearly was not cut out for military life. (His kowtowing and almost pathological sycophancy reminded me a little of the similarly pathetic but altogether more unctuous Arthur Storch character in Jack Garfein's

The Strange One, released a couple of years earlier but likely just proving there is one in every pack.) The fact that Obara can't be helped is just another lesson about the harshness of reality versus the purity of ideals that Kaji is going to have to learn. While at the start of Part I he is really a student who has not yet been pushed out into the world, by the time he gets to the army, he has experienced injustice in practice, not just in theory. The army will make a man out of him yet. Whether it's the man they want or not will remain to be seen.

There is a crucial moment in Part I where Kaji makes a connection with one of the leaders in the Chinese prison camp, an older man named Wang Heng Li (Seiji Miyaguchi). Wang has been the man whom Kaji has been most eager to have trust him, and even tries to blame Wang's distrust on why some things are going wrong in the camp. It's Wang that expresses that there is more to trust than asking for it, and more to being brave than being stubborn. He cites the fact that they are standing face to face, though staring across barbed wire, and connecting, bridging a divide between their people. It's the men you meet in life whom you find this common connection with that will define the social contract and make the way for real change, be it collective or personal. This encounter will end up being the most important for Kaji in terms of how he deals with the various types he meets from here on out. Which of them will provide the same connection?

It's also an important instruction from Masaki Kobayashi and co-writer Zenzo Matsuyama on how we should perceive what is going on in this movie. Regardless of the vastness of the landscape, it boils down to the people, the ones who connect with each other, and the ones who connect with us as the audience. This is a technique not dissimilar to

David Lean's. The British director used large backdrops and epic stories to create portraits of individuals, showing their courage and their fumbles in the face of situations that were larger than they were. For as awesome as the images we see are, for as breathtaking or soul crushing the locales, it all comes back to the man in the center of the frame.

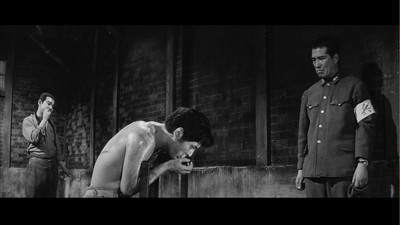

And make no mistake, in terms of visual power,

The Human Condition is awesome. Kobayashi and director of photography Yoshio Miyajima shot their film in black-and-white at a wide 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Within each frame, we see how barren the mine is and also how cramped the army camp; the unending battlefield versus the stifling forest they escape into (Part III). A figure placed within these vistas can appear lonely and overpowered, or if close enough in the foreground, powerful, eclipsing the world behind him. The size also makes close-ups all the more intimate, such as the scenes between Michiko and Kaji when she comes to visit him at his training base and they share a night in the storage shed. The image panel is all about them, all about their love, be it the tight shots of Kaji hugging her naked torso or when they lie down together. Conversely, when their marriage is strained, moving between them and their separate bed mats within this stretched visual space implies a canyon of loneliness and alienation between them.

Ironically, though the love of Michiko and Kaji is such an important aspect of his strength in the first arc of the movie--she is both a source of power and temptation--the separation of the pair is integral to Kaji's growth in the second. Her visit to the camp is a farewell of sorts. It's tender, and it's sad; Michiyo Aratama is heartbreaking in how she reacts to her husband clinging to her. After she is gone, though, a sour turn for Obara forces Kaji to stand up for something in the army barracks the way he failed to do back at the mining camp. When he slapped the boy Chen on the urging of a superior, he ignored his better instincts for how workers should be treated, and when his inability to push Obara over the hump leads to hazing and dark consequences, Kaji ends up advocating they enforce the army's judicial code. Again, it's ironic in that he ends up maintaining his own moral strength by embracing the army's stringent guidelines and achieves his own purity by insisting on them being followed exactly. It's a similar stance to the one he took at the mining camp, but this time he manages to make it work without letting authority lord it over him.

The isolation from his wife further allows Kaji to create a tighter sense of community in his new surroundings. When asked to train new recruits, he once again insists on reform, and he creates a solid unit by taking a more humanist approach to basic training. Earn their respect and loyalty with kindness, rather than brutality. Unfortunately, when battle does come to Manchuria, it comes too early, and the men aren't ready in terms of skill, but they do share the bond Kaji hoped for. The fighting turns out to bigger than they are, however. Combat is portrayed as pointless and demeaning, Kaji's unit hiding from the enemy like a giant game of whack-a-mole. One man is assigned to each foxhole, so though the experience is a commonly shared one, they are also isolated. The fewer there are to stand together, the more self-preservation becomes important, and Part II ends with Kaji abandoning what is left, running alone into a darkened wasteland, both in terms of its physical, bombed out appearance and the black clouds hanging in the air, and in the metaphorical sense. Our idealist is rushing headlong into an existential abyss.

The battlefield sequences are shot with a startling realism, including impressive explosions and large stagings of battle. The enemy is faceless and distant, but there is a starkness to the detail that rivals Kubrick's

Paths of Glory

or Spielberg's

Saving Private Ryan

. The size makes it alienating and impersonal. All the more interesting, then, that Kobayashi opens part III of the movie,

A Solider's Prayer, with a scene that brings the fighting right to Kaji: a hand-to-hand skirmish with a Soviet soldier. What we see of this, some of it as memories (memory plays a big part in this last third, Kaji's shame shown in freeze frame), is more surreal, the warriors framed in tight shots, a brightly lit night sky full of dark smoke behind them. Kaji is now a man taking charge of his own destiny, and that includes killing. A later one-on-one confrontation with Kaji's ideological rival (Nobuo Kaneko) in a labor camp pushes the expressiveness further, with Kobayashi and Miyajima lighting the beating like a scene out of a film noir. Likewise, eroticism is shot like these individual battles, with the camera moving in so tight, the images of these couplings are practically seen as abstracts.

This fifth chapter is concerned with Kaji's long trek home. Reminiscent of Kon Ichikawa's

Fires on the Plain, it first shows his hike across an empty wilderness, but soon he is consumed by the jungle that stands between death and freedom. Once inside, he no longer knows where safety lies. At the same time, he is denying the rule of the army, taking charge over a Corporal even though he is only a Private First Class, and eventually establishing his own mini-community. He and the few soldiers he is left with pick up a small group of peasants that they will try to shepherd to secure ground. Most of them won't make it out alive, but they still test Kaji's faith and his leadership, the beliefs by which he defines himself. He is becoming decisive, acting on what he knows to be right without hesitation or compromise. It's Kaji's way, like it or lump it.

In these final chapters, Kaji becomes a sort of Japanese Ulysses on his own Odyssey, his one goal being to get back home to his wife. Along the way, he encounters many perilous temptations, including several women who look to his strength and dedication with desire, but who fall under his single-mindedness much the way his wife had before them. He runs across leaders who refuse to deviate from their outmoded missions, make-shift refugee camps, and other soldiers who have lost their way, and who either seek the kind of leadership Kaji offers or the lawless alternative. In all things, Kaji emphasizes choice. Like I said, it's his way once you've come on board, but at each crossroads, any man in his company is allowed to decide which fork to take. Eventually, however, he ends up a POW forced into labor by the Russians, a predicament that baffles him. In his mind, it goes against the Communist ideal he would have expected from the Soviets, and it also takes him full circle: he is now subject to the very work conditions he once tried to stop. There is a great sequence where he confronts the Russian leaders with what he has learned and what he sees as being wrong with their behavior, but his impassioned speech is merely splatter against the language barrier. Oh, futility!

Tatsuya Nakadai is still a working actor to this day, and he has appeared in a number of great films, including starring in

Kurosawa's

High and Low,

Ran, and

Kagemusha. He even worked with Kobayashi again in

Samurai Rebellion,

Kwaidan, and

Harakiri. The acting range he displays in

The Human Condition is nothing short of extraordinary. Though we only glimpse his character over a handful of years (and, indeed, Nakadai played him for almost as long as the time that passed in the script), we see Kaji go through a full arc. Call it a practical education if you will, growing from an idealistic youth with more stubbornness than technique to an experienced soldier that can enact a philosophy in actual situations and all the way to rock bottom. Just like Ulysses, the final leg of Kaji's journey is spent in the trappings of a beggar, though unlike the hero of myth, Kaji undergoes this development for real.

The ending of

The Human Condition is bleak. Kaji spends the final scenes on the frozen Manchurian countryside, a tragic turn given that this is where he has run to in order to escape Siberian imprisonment. The world we see through the camera eye is now bleached out, flattened, a blank slate that cannot sustain life. If we continue to consider

The Human Condition with an existential mindset, this is a perfect metaphor for the plight of modern man. Sticking to one's ideals, as Kaji does up unto the very end, is a noble pursuit, but one met with more punishment than reward in a world that demands conformity override individual concern. (Indeed, Kaji's problems with the Red Army's approach to socialism is that it swallows men whole in order to just make them part of the same old injustice.) Kaji has gone as far as he can go, and that is a place where he is completely alone, in a landscape that is literally cracking under his feet. Yet, he stumbles onward, his last thoughts being of his wife, the beacon he has followed, the lighthouse of his principles. In one light, this is tragedy, a man who can't be broken but who breaks all the same--that is the human condition, our moral code still depends on our physical body--but in another light, it's a triumph of the same. One can go on but need not give in.

The last shot pulls away from the figure at rest, leaving it rather than zooming in to join it. The reversal takes us from the personal, back to the widescreen picture, back into the world, carrying the image of the man in the snow with us.

The Human Condition has been out of print for many years, and there aren't kudos big enough for Criterion having brought it back to audiences in such spectacular fashion. I've been kicking myself for nearly a decade now for not buying the original three-disc release after spotting it used shortly after getting my first DVD player. In all that time, I hoped Criterion would put out a set and I could finally correct my mistake. To see Kobayashi's masterpiece at last and in such fine packaging--a beautiful looking multi-covered book, a fourth disc full of extras, a remarkably clean transfer--it's been well worth the wait.

The Human Condition is an enriching, incomparable cinematic experience.