Given that I write more reviews than what you see here, below is a list of non-Criterion films I covered in the past month that may be of interest to Criterion fans.

I'm definitely going to get a review up before I go to Dallas this weekend for Free Comic Book Day. I hope, I hope. It would be my first week of no reviews if I fail. I've actually got both of May's Louis Malle releases to watch, so it will likely be one of those.

IN THEATRES...

* Last Year at Marienbad, the Alain Resnais classic is doing the revival rounds.

* My Blueberry Nights, Wong Kar-Wai's first English-language film gets overanalyzed yet again.

* Shine a Light, where Martin Scorsese meets the Rolling Stones to create an IMAX concert experience.

ON DVD...

* Dam Street, a Chinese film, directed by Li Yu, showing the stigma and long-lasting effects of Communism's strict moral code in the 1980s/90s on a teenage girl who becomes pregnant.

* The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, one of the best movies of last year. A tremendous achievement by Julian Schnabel.

* The Pied Piper of Hützovina, a documentary on Gogolo Bordello's Eugene Hutz returning to the Ukraine.

* Starting Out in the Evening, in which Frank Langella gives a tremendous performance as a writer at the tail end of his career and facing the outer edges of obscurity.

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

Sunday, April 20, 2008

THE DELIRIOUS FICTIONS OF WILLIAM KLEIN - ECLIPSE SERIES 9

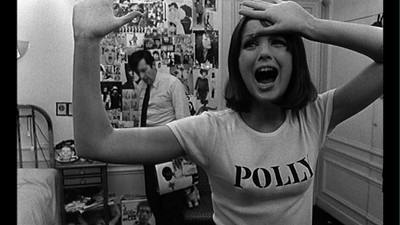

I have to admit, the name William Klein is new to me. I can admit this without shame. Having worked in a variety of entertainment-related retail establishments, the first lesson to be learned in all of them was that there is a lot more out there than one person could possibly be aware of, and every single one of those things you have never heard of, no matter how obscure, strange, or even bad, is someone's favorite thing ever. To prove this, I recently ran into one of my former co-workers from a video store job I had a couple of years ago, and we were talking about recent films we had seen. "You know what has me excited?" he said. "That Criterion boxed set of William Klein movies they have coming out. Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? is one of my favorites."

So, there you go. William Klein fits the criteria. He is obscure and strange, but he's also someone's favorite. If there is one thing he is not, however, it's bad. Far from it.

An American ex-pat who set up shop in Paris in the 1940s, Klein began his artistic career as a painter and then as a photographer. From what I've read (and there is an interesting biography with examples of his photographs here), he gravitated to bold and iconic early 20th Century art styles, emulating aesthetic schools that sought to change how artists approached making art and how audiences viewed it. When Klein turned to photography, he used a variety of tools, including wide-angle lenses and different techniques for developing the picture. He sought to find a way to bring abstraction to photo documents, to capture life not necessarily as it was, but aided with the artistic eye. He took photos for the purposes of art, showing his work in galleries and publishing monographs, and as commerce, photographing fashion for magazines.

In the 1960s, he changed his mode of expression yet again, embracing motion pictures and starting the stage of his career that he would sustain the longest. As with photography, he split his interests between capturing real life and reshaping it to his own designs, making both documentaries (notably Muhammed Ali: The Greatest

Delirious Fictions is right! Whoever came up with that title deserves some kind of award. I can't imagine a better way to describe Klein's cinema. His 1966 film Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (101 minutes; black-and-white) is a whirling dervish of styles and ideas. Every shot is an event, every turn of the narrative a new adventure. Also, interestingly enough, when Klein wasn't using film to chronicle reality, he was critiquing it, and he had a surprisingly intuitive ability to pick-up trends that would continue far into the future, making his visions as insightful today as they were when he concocted them.

Polly Maggoo (Dorothy MacGowan) is a bucktoothed, freckle-faced American girl working as a model in Paris. She is all the rage, the fantasy girl of the faraway Prince Igor (Sami Frey) and the obsession of television reporter Gregoire (Jean Rochefort), who is filming the gamine for his journalistic personality show Who Are You?. In between this fantasy figure and this supposedly grounded intellectual is a whole culture obsessed with Polly, fashion, and the new. The film begins with a fashion show where an avant-garde designer (Jacques Seiler) displays his new line of dresses made from bent sheets of aluminum, and the influential magazine editor Miss Maxwell (Grayson Hall, zinging Diana Vreeland) declares that he is magnificent and that he has reinvented the concept of woman. Apparently, the entire female gender was out of date.

Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? casts a wide satirical net, but since its biggest target is a staple of popular culture, it's rather prescient of Klein to see how far his net needs to go. Though the eye of his storm is the over-inflated importance of the fashion world, his Polly is really a mirror to the society that worships her. When we gaze at her gazing at us from a magazine cover, we're really looking at ourselves. Gregoire claims to want to get to know the real Polly, but he really wants to see her conform to his preconceived theory than truly uncover the girl behind the beautiful face. So, too, is Prince Igor imagining her for the role she plays in his own Cinderella story. His wild daydreams show her in a pretty standard fairy tale, but the longer these fantasies go on, the more an independent Polly asserts herself and the less he likes it.

Cinderella as a metaphor comes up time and again in Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? How it pertains to Polly changes with each telling, each person having their own idea of what the glass slipper would be, allowing Klein to emphasize the cruel fetish of male possession. This also ties into fashion, which abstracts the female form and jails it in absurd concoctions. More than once, Polly is accused as a con artist that is part of some great duping of the feminine mind. Playing Polly, MacGowan stays fabulously above the fray. Though she may be a cypher in many eyes, Klein lets her be a real girl, herself, never hemmed in by the camera lens.

Of course, Klein never lets anything be hemmed in by the lens. His camera is always moving, if not literally, then by never lingering too long on one shot, cutting from one elaborate staged composition to another. There is no technique he isn't willing to employ, including using stills and freeze frame images, jump cuts that drop frames out of a sequence, musical numbers, and even animation. His sets are like art installations, populated with fads and objects of '60s modernism; overpopulated, you might say, to the point that they look futuristic. (One would suspect Roman Coppola watched Polly Maggoo when putting together CQ

Arguably, Klein's inability to sit still predicts the attention deficit disorder we find in current pop culture. As much as Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? parodies the 1960s, it also seems like Klein had a crystal ball where he saw MTV, the paparazzi, and other aspects of our celebrity-obsessed media. He even beats Andy Warhol to the "fifteen minutes of fame" punch by a couple of years, shining a light on the fickleness of public taste. By the end of the movie, Polly Maggoo is out of style, and people are moving on to find new faces to love.

And so, too, do we move on. Klein's next full-length film was 1969's Mr. Freedom (92 minutes; color), an unrestrained evisceration of America's aggressive foreign policies and its unwavering sense of Manifest Destiny. A low-rent superhero movie, complete with kitschy costumes and strange inventions (a teleportation tube straight out of Jack Kirby!), it's a blistering comedy and the bluntest of satires, a comic book movie in a total pop-art fashion.

Mr. Freedom (John Abbey) is the top agent at Freedom Inc. A sheriff by day, he ditches the cowboy garb when he goes into battle, donning a red-white-and-blue superhero suit put together with padded muscles and football gear. After dealing with looters from a race riot on America's streets, Mr. Freedom is summonsed to headquarters by Dr. Freedom (Donald Pleasance), a guiding light on a TV screen. The first several floors of the Freedom building are taken up by oil companies and General Motors, followed by an agricultural company and personal-care product manufacturer Unilever. Top floor is Freedom Inc., the biggest of the businesses, built on top of the others. Hey, is this 1969 or right now?

Mr. Freedom is sent to France, where the Communists are flooding the borders by way of Switzerland. The evil Moujik Man (Philippe Noiret) and his twisted cohort Red China Man (played, I kid you not, by a giant dragon balloon) have already taken out Mr. Freedom's French counterpart, Captain Formidable (Yves Montand), and if the Reds aren't stopped, France will fall, opening a hole for the rest of Europe to tumble after. The anti-French rhetoric spouted by the Freedoms is, again, eerily familiar. Forty years later, and the right-wing pundits are still saying the same thing, questioning France's fortitude and taking all the credit for carrying Europe in both World Wars. It's scary that progress has been so poor in all this time that a farcical film this old can still be so right on the money.

Once in France, Mr. Freedom proceeds to bully his way toward his goal. Gathering his forces, a variety of Freedom-loving heroes played by such luminaries as Delphine Seyrig, Jean-Claude Drouot, and Serge Gainsbourg (who also contributes music), Mr. Freedom intends to make the world safe for the American way, but his twisted self-belief makes him blind to the needs of the situation. Though he claims he is willing to negotiate with his enemies, his main negotiation technique is "Do what I want, or else." Super French Man (another balloon) insists he can defend his own country, but instead of capitulating, Mr. Freedom saps the will of the French hero's soldiers, using hypno glasses to win their hearts and minds. He goes too far, though, when he guns down Red Maria (Catherine Rouvel), and the people turn against him. They take to the streets protesting the American presence in Paris, but despite overwhelming popular opinion against him, Mr. Freedom refuses to change course. He will fight it out to the bitter end.

Again, is any of this sounding familiar? Though William Klein--who is credited as writer, director, and designer--was criticizing the U.S. policies of his time, particularly as it pertained to Vietnam (one delicious sight gag is of a poster declaring that JFK is wanted for treason) and resistance to the civil rights movement, his portrayal of the overbearing cowboy with an exaggerated sense of entitlement using divisive ideology and empty platitudes to justify aggressive greed dials right in to much of our nation's current state of unrest. In his final speech, Dr. Freedom declares that the problem is not with spreading democracy to the world, but that they have chosen to bestow it on people who aren't ready to accept the blessed gift by choice. Thus, force it on them now, because they will thank us later. (Surprisingly, religion plays very little role in this. It seems to be a little too complicated for the single-minded Mr. Freedom, who is nonplussed by his meeting with Jesus-stand-in Christ Man (Sami Frey) and doesn't recognize the symbolism in the stigmata he later suffers.)

Mr. Freedom's satirical technique is pounded out with the meatiest of fists, that's to be sure, but it's also raucous fun. The movie is colorful and outrageous, and Klein has a gas with comic book conventions. The free-for-all brawls can sometimes be a little too out of control for my money, but the basic mission of Mr. Freedom and the garish costumes of his allies and enemies are fantastic in their excess. Apparently this film was dismissed upon its initial release (and delayed almost a year due to the May 1968 political turmoil in France; the movie even contains documentary footage of earlier political demonstrations). Its lack of critical and box office success could possibly have been because Klein's jabs hit a little too close for comfort. The time is ripe to rediscover this one, though. Given the current political climate and the popularity of superhero movies, Klein's candy-coated dissent should finally go down as the director always intended.

It was eight more years before William Klein made the third of his "delirious fictions." The Model Couple (1977; 101 minutes; color) is my least favorite of the trio (and, really, the first film is easily the best), but it only speaks to how good The Model Couple's predecessors are that this creatively rich movie cold ever possibly come in third. The Model Couple imagines a contemporary France that has a Ministry of the Future. Determined to design a city to meet the needs of people facing the end of the century, they choose an ideal husband and wife to isolate in a specially designed apartment so they can be monitored and tested. Once classified, the Ministry can then plan for a tomorrow perfectly suited to the French citizens.

Jean-Michel (Andre Dussolier) and Claudine (Anemone) were chosen for their high percentage of average traits (77%, they are told). Once in their apartment, they are hooked to wires, set about to tasks, and submitted to a variety of experiments to map the outer boundaries of their relationship and the conditions they will submit to. They are poked and prodded by two psychosociologists (Jacques Boudet and Zouc), and the entire procedure is recorded and shared with the television viewing audience. It's a little like the "Big Brother" TV show but with at least a semblance of social value, and the host of the program (Andre Penvern) and his panel of commentators is easily as annoying as the constant chatter streaming out of the flapping maws of pundits on cable news.

Initially, while the program maintains the illusion of wanting to uncover the couple's true wants, eventually when results stop conforming to what is convenient to the Ministry, the psychosociologists start to try to manipulate Jean-Michel and Claudine into conforming to the anticipated results. (Making them just like Polly Maggoo and the whole of the world under Freedom Inc.) As Klein sees it, the future is not always helpful, and all the technology and the gadgets it brings could just as likely enslave the users as free them. The experiment also begins to take its toll on both the administrators and the subjects, causing them to go a little stir crazy. Even worse, the public interest starts to wane, and a new strategy will have to be formulated or the house might be shut down. In a media culture that is constantly feeding on itself, there is always a need for a new meal.

The Model Couple is Klein's least detailed production. The sets and the many props are painted in solid colors, with the walls being totally white. Klein focuses most of the art direction on the gadgets, including the elaborate monitoring systems that get attached to Jean-Michel and Claudine. Though he doesn't rely on the rapid cutting or even the complicated compositions of Polly Maggoo, he does maintain a sense of playfulness. There are multiple sequences where the footage is shown in double-time while being underscored with narrative songs composed by Michel Colombier and performed by Hugues Aufray, a '60s performer known for his French adaptations of Bob Dylan tracks. There are also Godardian experiments in sound, including a scene where the couple notices the sound of their words is out of sync with the movement of their lips. In fact, there is a lot of Godard in the political sloganeering and the debates the psychological experiments inspire.

One linking element between all of these films is television sets. In each, we see the characters appearing on television shows and both being watched and communicating through closed-circuit monitors. In Polly Maggoo, a fantasy sequence is shot from Polly's point of view as she sits down at a table for a feast, and she sees herself on a television on the other side of the banquet. In Mr. Freedom, Dr. Freedom only appears as a head on a screen, and Mr. Freedom wears a mini-television communicator on his wrist. By The Model Couple, the entire lives of the characters have been reduced to signals bounced from one TV to another. Though Klein's targets are different in each picture, each subject is somehow affected by the growing presence of celebrity culture, television, and media scrutiny.

William Klein made his last film in 1999, a documentary about Handel's Messiah

For technical specs and special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

This DVD set will be released on May 20, 2008.

Saturday, April 19, 2008

DEATH OF A CYCLIST - #427

A bicyclist rides up an empty road in the evening. Just as he passes the horizon and disappears out of sight, there is a crash. A motorcar comes swerving into view and stops, its tires screeching. A man and a woman emerge and go to the downed biker. The man says the cyclist is still alive, but the woman, who was driving, urges him back into the car. They speed away, leaving the crash victim where he lay.

This is the opening of Juan Antonio Bardem's entertaining, suspenseful 1955 film Death of a Cyclist. There is no fuss, we are right in it.

As it turns out, the woman, Maria Jose (Lucia Bose), is married, and not to the man in the car. Juan (Alberto Closas) was her sweetheart before the war, but she married a rich man (Otello Toso) before he could return. Now they are lovers in secret, and helping the man they ran down would expose the adultery. This may not be that big of a deal for Juan, because he has nothing. Even his job as an assistant professor at the university was secured for him by his brother-in-law. Maria Jose, on the other hand, has plenty to lose. She enjoys her high-society existence, and even dares to suggest that it's her marriage that makes her affair with Juan possible. She doesn't say it outright, but the implication is clear: there is no romance in poverty.

Bardem's film is a little like a Spanish version of Renoir's Rules of the Game. Juan and Maria Jose are part of a class system that allows them to leave a man of lesser standing to die on the pavement. It's significant that the travelers are on the road going in two opposite directions, one in an expensive machine and the other on a simpler device. The bicyclist was likely returning home from work, and Maria was in a hurry so that she would not be late for her own dinner party. The division could not be more clear.

Really, the entire film is about divisions. Though the story is a rather standard murder plot, Bardem is using the pair's act of callous disregard as an excuse to extend a larger social critique. Lines are drawn in multiple instances to show the gulf between the common people and Spain's upper crust. The overcrowded tenement where the dead man lived is nothing like the large houses where his killers reside. Juan's lack of success is in stark contrast to his brother-in-law and Maria Jose's husband, Miguel. There is also a marked difference between the young and the old, between Juan and his students, particularly Matilde (Bruna Corra). Matilde has the misfortune of giving her oral exam when Juan sees the report of the hit-and-run in the newspaper, and instead of acknowledging that her assignment was halted by his own panic and not anything she did wrong, he flunks her. Her quiet crusade to achieve some kind of redress ends up being the catalyst for Juan's moral transformation. He is reminded of his own youthful fire before the war destroyed all of his beliefs. He is inspired not just by the passion Matilde evokes in her fellow students, but also by the compassion she shows him. Even though she is the one who has been wronged, she intuits that there is some kind of turmoil in Juan and would just as soon see it resolved as have her rightful grade restored.

From a filmmaking standpoint, Bardem and editor Margarita Ochoa show the criss-crossing interests through innovative and clever cutting. Virtuoso scenes of juxtaposed action push the story forward. This is most effective in the back-and-forth jumps between Juan's lonely torment at his mother's home and Maria Jose's attempts to cover her guilt amongst their society friends, including Juan's sister and her husband. Bardem jumps from the blowhard brother-in-law pontificating at Maria Jose's party to Juan watching a similar grandstand at a different party projected as part of a newsreel in a movie theatre, Isidro B. Maiztegui's melodramatic music ironically underscoring the political puffery. This shows us further how divorced these wealthy citizens are from reality, that they could just as easily be concoctions for the movies as they are actual people.

That is just one of the many inventive cuts that Bardem stacks in a particularly dizzy montage. In one instance, Juan exhales cigarette smoke in his bedroom, and the film jumps to Maria Jose fanning smoke away from her face across town in her own bedroom. The exhalation she chokes on is her husband's, but the connection is fairly obvious. Bardem uses similar connectors throughout the film, sometimes to lace pieces together, sometimes to pull them apart. He's showing us the various levels of the hierarchy, while also exposing the inconsistencies.

The most active agent for pointing out the class differences is also the major agent for Death of a Cyclist's plot momentum. The piano-playing art critic Rafa (Carlos Casaravilla) saw Juan and Maria Jose on that road that day. His revelation is almost like one of Bardem's clever editing set-ups, but without the edit. When Maria Jose's asks him the name of the tune he is playing, he says, "Blackmail," and the proceeds to explain the story behind the song, about a man and a woman in a car on their way to somewhere they aren't supposed to be. Rafa gleefully toys with the pair, refusing to show his cards, taking pleasure in their torment. He sees himself as the man in the middle, a lower-class citizen who is tolerated by the fancy crowd because he is entertaining. Now they can entertain him. It's an act of class revenge, but Rafa's own bid for social standing lacks the purity of a real revolution, and so he risks being a failed villain rather than a righteous crusader.

Without Rafa, however, Juan and Maria Jose would not be put on their opposing paths for dealing with the murder. While Juan seeks out what the police and the rest of the world knows about what happened, Maria Jose only cares about what Rafa knows. This means that Juan becomes concerned with how his actions affect those around them, be it the cyclist's widow or students like Matilde, while Maria Jose is only concerned with how it affects her. It becomes clear to Juan that he can't continue on as he has been going, that he must take responsibility for his choices, he is not above the law. He realizes that the supposed nobility lacks any real nobility, that these divides we have been seeing are unfair. The question is whether or not he can make Maria Jose have a similar moral awakening.

Despite the socially conscious underpinnings, Bardem's film is no more a message picture than Renoir's was. Its surface trappings are that of a thriller: who knows what, and what lengths will the guilty go to in order to stop that information from coming to light. As far as the tone and pacing of the film is concerned, Bardem also creates a division through technique. The scenes that directly relate to the killing are feverish, with Bardem employing his quick cuts and never lingering too long on one scene. Death of a Cyclist only stops to breathe when Matilde is on the screen, shifting gears from being a race against the clock to being a picture about moral issues. Though I wouldn't classify Death of a Cyclist as a film noir, there are hints of noir tropes in this dichotomy. Maria Jose, the brunette, would be the femme fatale in a Hollywood noir, while the lighter-haired Matilde is the noble and pure woman who sees redemption for the male heavy. Were this, say, Out of the Past

Ah, if only it were that simple. If Juan was up on his noir conventions, he'd know that the past always catches up with you, that the bad guys the hero wronged will always find the farm he's hiding out on. Bardem sees the difference between a moral victory and true change, and thus Death of a Cyclist ends where it began, on the same patch of road where the crime took place. The question that remains is if Juan's newfound conscience has enough cosmic influence to mean justice will be served. If we are truly on the symbolic flipside, then it will be poetic justice, and I must say, there's certainly nothing wrong with that.

Death of a Cyclist has one of the best photographic covers I have seen in a good long while. The choice of the right still from the movie can have a lot of impact (no pun intended), and the single image used as the front of this package is intriguing, showing us the basic set-up without saying too much. The well-placed logo and the decision to use a fractured font add to the sense of urgency while also suggesting danger. The art team at Criterion take it even a step further, and when you open the case, the image on the top of the disc is sequentially only a few more frames ahead of the cover still--Juan has reached the cyclist--and like two comic book panels, it creates the illusion of motion even before the DVD is inserted into the player.

Also smartly chosen is the DVD's sole video extra, the 2005 documentary Calle Bardem. The 40-minute feature gathers Bardem's friends and collaborators to share their experiences with and impressions of the late director. What emerges is a portrait of a filmmaker who walked it as he talked it. A lifelong member of the Communist Party, Bardem sought to fuse his love of Hollywood with a more socially conscious cinema based on the Italian Neorealist example, a synthesis that is on display in Death of a Cyclist. (The accompanying booklet also has Bardem's 1955 cinema manifesto, which explains his ideas further.) What ends up being interesting is how this dichotomy also informed Bardem's personal life. He was known alternately as a fun, compassionate individual and a dogmatic tyrant, an entertainer and a teacher.

You can't just walk away. Particularly when the future is rushing in the opposite direction.

Wednesday, April 16, 2008

PADDLE TO THE SEA

Though not part of the Criterion Collection proper, this disc is released through the studio's parent, Janus Films, in conjunction with the main brand.

Made in 1966 by filmmaker Bill Mason, Paddle to the Sea is a short film based on the award-winning children's book by Holling C. Holling . Its narrative is simple, as are its pleasures. One winter a sick boy in the mountains of Ontario carves a canoe out of wood, a Native American stridently riding in its belly. On the bottom of it he christens it Paddle to the Sea and adds instructions that whoever finds the boat should put it back in the water.

. Its narrative is simple, as are its pleasures. One winter a sick boy in the mountains of Ontario carves a canoe out of wood, a Native American stridently riding in its belly. On the bottom of it he christens it Paddle to the Sea and adds instructions that whoever finds the boat should put it back in the water.

The boy leaves the boat in the snow, to be taken down the hillside by the thaw. The thaw plants it in a mountain creek which then takes it to Lake Superior, and through a course of many more rivers and lakes, eventually spits the little boat into the Atlantic Ocean. Part nature film, part travelogue, Mason and crew chronicle the boat on each step of its journey, its encounter with fish and fauna, as well as calamities both natural and manmade. There is no dialogue or conventional story, just the journey, given a sense of wonder by the continuous narration. The voiceover makes the tiny object seem like something grand, making all creatures that see it a part of the trek. To lay your eyes on Paddle to the Sea is to become invested in his journey.

Paddle to the Sea works on multiple levels. The beautiful photography and the adventure inherent in the story act as a spoonful of sugar to make the medicine go down. Only the most astute or cynical of children will realize that all of this is merely an excuse to teach them a thing or two about nature and possibly inform them of the dangers of pollution. Older film fans will enjoy imagining the crew getting the various shots. How silly they must have looked dropping this tiny boat in the way of an ocean liner, and I'd love to have heard them convincing canal operators to open the locks to let Paddle to the Sea slip through.

There is a beautiful lack of fuss around this story and the dreams that fuel it, and I wonder how apropos it would be today. I know similar fantasies were fairly universal when I was young. I invented my own plans to build tiny boats and send messages out to sea, hoping beyond hope that someone would find my vessel and send me a greeting from somewhere far beyond my crappy little suburb. My boats were mainly cardboard or uncarved wood, with rudimentary sails that had my address scrawled on them. When you're young you skip over pesky science, never once considering that paper gets wet and turns soggy or that water makes ink run. Never mind, too, that I was dropping my schooners into a larger sewer canal that ran through Canoga Park in the San Fernando Valley in California. Who knows what kind of gratings and pipes they ended up in.

Today, Paddle to the Sea would be fitted with a GPS and he'd have his own url carved on the bottom so people who find him could log on and track where he's been, like those stupid "Where's George?" rubber stamps that deface many a dollar bill. The very thought kind of sucks the magic right out of it, doesn't it? As an uncle myself, I charge my brethren with getting this film in the hands of their nephews when they are still young enough to be captured by the Luddite wonder of it. Jack London's stories are persevering through the technological age, there's no reason that Paddle to the Sea can't, as well.

Because when you sweep up the wood shavings and look at the man in the boat, he really sits in that canoe for all of us. To get caught up in his wanderings is to look at the larger struggles of man himself. At one point, as Paddle to the Sea circles a man-made whirlpool, the narrator wonders if he will get out of this pickle. For, as he has pointed out, Paddle to the Sea has no paddles, nor the arms to paddle them if he did. It's a feeling everyone has at one time or another: life is looming large before us, and we have not been given the tools for which to deal with it. Do we give in? No, we stick to our mission and sail on. There's a big ocean out there, and there is no telling where the currents may lead.

This DVD will be released on April 29, 2008.

Made in 1966 by filmmaker Bill Mason, Paddle to the Sea is a short film based on the award-winning children's book by Holling C. Holling

The boy leaves the boat in the snow, to be taken down the hillside by the thaw. The thaw plants it in a mountain creek which then takes it to Lake Superior, and through a course of many more rivers and lakes, eventually spits the little boat into the Atlantic Ocean. Part nature film, part travelogue, Mason and crew chronicle the boat on each step of its journey, its encounter with fish and fauna, as well as calamities both natural and manmade. There is no dialogue or conventional story, just the journey, given a sense of wonder by the continuous narration. The voiceover makes the tiny object seem like something grand, making all creatures that see it a part of the trek. To lay your eyes on Paddle to the Sea is to become invested in his journey.

Paddle to the Sea works on multiple levels. The beautiful photography and the adventure inherent in the story act as a spoonful of sugar to make the medicine go down. Only the most astute or cynical of children will realize that all of this is merely an excuse to teach them a thing or two about nature and possibly inform them of the dangers of pollution. Older film fans will enjoy imagining the crew getting the various shots. How silly they must have looked dropping this tiny boat in the way of an ocean liner, and I'd love to have heard them convincing canal operators to open the locks to let Paddle to the Sea slip through.

There is a beautiful lack of fuss around this story and the dreams that fuel it, and I wonder how apropos it would be today. I know similar fantasies were fairly universal when I was young. I invented my own plans to build tiny boats and send messages out to sea, hoping beyond hope that someone would find my vessel and send me a greeting from somewhere far beyond my crappy little suburb. My boats were mainly cardboard or uncarved wood, with rudimentary sails that had my address scrawled on them. When you're young you skip over pesky science, never once considering that paper gets wet and turns soggy or that water makes ink run. Never mind, too, that I was dropping my schooners into a larger sewer canal that ran through Canoga Park in the San Fernando Valley in California. Who knows what kind of gratings and pipes they ended up in.

Today, Paddle to the Sea would be fitted with a GPS and he'd have his own url carved on the bottom so people who find him could log on and track where he's been, like those stupid "Where's George?" rubber stamps that deface many a dollar bill. The very thought kind of sucks the magic right out of it, doesn't it? As an uncle myself, I charge my brethren with getting this film in the hands of their nephews when they are still young enough to be captured by the Luddite wonder of it. Jack London's stories are persevering through the technological age, there's no reason that Paddle to the Sea can't, as well.

Because when you sweep up the wood shavings and look at the man in the boat, he really sits in that canoe for all of us. To get caught up in his wanderings is to look at the larger struggles of man himself. At one point, as Paddle to the Sea circles a man-made whirlpool, the narrator wonders if he will get out of this pickle. For, as he has pointed out, Paddle to the Sea has no paddles, nor the arms to paddle them if he did. It's a feeling everyone has at one time or another: life is looming large before us, and we have not been given the tools for which to deal with it. Do we give in? No, we stick to our mission and sail on. There's a big ocean out there, and there is no telling where the currents may lead.

This DVD will be released on April 29, 2008.

Sunday, April 13, 2008

SILENT OZU: THREE FAMILY COMEDIES - ECLIPSE SERIES 10

The Eclipse Series is the Criterion Collection's way of bundling specific segments of a director's career under one banner. Usually focusing on the less well-known pieces of a filmmaker's oeuvre, the Eclipse boxes come without any bells or whistles, presenting the movies on their own without extras or the meticulous restoration that is usually applied to their more high-end releases. Those kinds of DVDs take a long time to produce, and by taking this approach, the company can take films from the back of the line and get them to the public faster. Thus, the three movies in Silent Ozu - Eclipse Series 10, further subtitled Three Family Comedies, don't have to sit on a shelf waiting for Yasujiro Ozu's more venerated films to work their way through the system and clear up space for them.

Ozu already has his own Eclipse box, and is actually the first director to be a repeat in the collection. Late Ozu was the third in the series, and it showed the director at the end of his long career, making his final films in the '50s and '60s. Silent Ozu swings us back to the other end, presenting three of the Japanese master's early films from the 1930s. Though Ozu had actually begun working in the previous decade, the '30s saw him settling into the type of work that would define his career: films about family and their everyday lives, how they get by and how they deal with the rapidly changing onset of modernity while still keeping the core of family intact. He was already working with screenwriter Kogo Noda, his lifelong collaborator, to achieve a balance of tender humor and poignant drama, establishing a sense of calm sentimentality that would give even his heavier pictures a feeling of being free from Earthly gravity.

Those were all lessons that would serve him well once Ozu transitioned into talkies, but which began forming here, in the silent era.

* Tokyo Chorus (Tokyo no korasu) (90 minutes - 1931): Four years into filmmaking and Ozu made his twenty-second picture, a bittersweet light drama about a struggling family in Tokyo. Though I realize this boxed set is billed as "Three Family Comedies," this is more a comedy as far as its lightness of tone than it is a laugh-out-loud effort. It's more the traditional theatrical definition of comedy, working in opposition to tragedy. In other words, everything turns out all right.

You could actually say that the comedy comes from the foolhardy ego of Shinji Okajima (Tokihiko Okada) needing to be deflated in order for him to grow up. Beginning in his school years, Okajima is the class cut-up making life difficult for his teacher, Omura (Tatsuo Saito). Underneath the antics, though, Ozu is introducing his larger themes of poverty and social standing. Much of Okajima's joking is covering up for the fact that he is not as well-off as his fellow students, his uniform is not up to snuff.

Cut to post graduation, and Okajima is now a family man with three children and a caring wife (Emiko Yaguma). He works for an insurance company and is getting on fine in his daily life, but as we will see, he is still caught somewhere between his idealistic youth and his real responsibilities. Hence, when his son (Hideo Sugawara) begs for a bike, Daddy promises the boy one to be a good guy and cool father; when the older office worker (Takeshi Sakamoto) gets fired from his firm, Okajima stands up for him, showing his coworkers that he has the mettle to oppose injustice. This only gets him fired, as well, and the rest of Tokyo Chorus is spent watching Okajima learn how to navigate his new station in life. Ozu adopts a realistic, socially critical eye to view Okajima's struggle, showing the poverty and employment on the city streets. Okajima is still left-of-center as far as this social commentary is concerned: he's still the clown from the early scenes, the happy dad from a family drama. Part of his new education, which is once again aided by teacher Omura, is to get more in line with reality, to drop the act and the pretense of pride, and face life with a clear vision. Ironically, what he will discover is that by growing up and accepting adulthood, he is once again free to enjoy himself.

In some sense, in the way Ozu peeks in on the children at play and juxtaposes it against the more serious adult concerns, I am reminded of his later family comedy Good Morning. In a larger sense, however, Tokyo Chorus shows the early groundwork for what would become the classic Ozu dynamic: a portrait of a family, a struggle between generations in the face of change, and a soft tone that handles both the happy and the sad with an even hand that smoothes it all out and shows us that it's all one cake and is all covered in the same frosting. Even visually, Ozu is already applying his static camera technique, keeping his shots grounded and maintaining a quiet, unobtrusive directorial presence.

* I Was Born, But... (Umarete wa mita keredo) (90 min. - 1932): If I Was Born, But... reminds you once again of Good Morning, this time it's for a very good reason: the later film used this one as a jumping-off point. Written by Akira Fushimi from a story by James Maki, I Was Born, But... is the story of two grade-school-aged brothers (Hideo Sugawara and Tomio Aoki) who have newly moved to the suburbs, where they find the neighborhood kids to be rougher and more territorial than what they are used to. The comedy of the social interaction amongst the children is reminiscent of the Our Gang/Little Rascals shorts, with kids acting of one mind, running back and forth across the screen looking for trouble. An added element of Ozu's film, however, is the adult perspective and that childhood awareness that adults just don't get it. When the boys are discovered to have skipped school to avoid getting into a fight, dear ol' Dad (Tatsuo Saito again) tells them to just ignore the bullies and they will go away. The boys know this won't work, and so they have to invent other schemes to get out of harm's way. One always has to wonder how parents seem to forget so much of what the world is like! Ozu even shows the level of the father's selective blindness, using subtle cutting to show the parallels between the pecking order in the office and the classroom.

After the bully problem is dealt with, the boys become part of the gang, joining in bizarre death-and-resurrection pantomimes and eating sparrow's eggs for strength--the kind of wild ideas that kids invent based on overheard facts and half-truths and that make for great movie comedy. The children are fantastic performers, and I Was Born, But... comes alive every time they are on screen, borrowing its comedic approach straight from the playground. (I love Tomio Aoki--also called Tokkan Kozo--when he

does a little side bit of comedy business straight from Tinsel Town.) Director of photography Hideo Mohara (who also doubled as the editor) lets his camera move when the kids do and lets it settle when they settle. Ozu's ensemble is comfortable and funny, coming off as natural performers rather than Hollywood caricatures.

Eventually, the games shift into a battle over whose dad is more important, and the final act of the film is concerned with the brothers discovering for the first time that their father is not everything they imagined him to be. To them, their father is the boss, and seeing him in a situation where he is actually the underling confuses them. After a violent row, their dad remembers how daunting and disappointing the intricacies of the social order can be for a child. The lesson he has to teach them about how to get along is remarkably similar to the one they learned in spite of his advice in regards to the bullies: tomorrow is another day, and another chance to take things head-on and make life better. It's as touching as it is funny, and it's right on the money.

* Passing Fancy (Dekigokoro) (100 min. - 1933): A father-son relationship takes center stage yet again. This time, the father is happy-go-lucky Kihachi (Takeshi Sakamoto), a single dad who works in a brewery to give his son an education. The son, Tomio, is played by Tomio Aoki from I Was Born, But..., and he's already a couple steps ahead of dad in the smarts department. The two live simply in Tokyo, spending their nights at the restaurant down the street, palling around with dad's co-worker Jiro (Den Obinata). After an evening of entertainment, the two men meet Harue (Nabuko Fushimi), a young girl who is down on her luck. Jiro is suspicious of her, but Kihachi is immediately smitten. He gets her a job in the restaurant and sets to courting her. Only, she likes Jiro, who continues to think she's the wrong kind of woman. Kihachi, ever the loveable fool, is even enlisted by Harue's boss (Coko Iida) to try to change Jiro's mind.

Takeshi Sakamoto's sweetly comic performance dominates the picture. It's the sort of defining performance that makes an actor's career. A naturally genial screen presence, his smile sets Passing Fancy alight even as his character hits a rough patch. Broken-hearted over Harue, Kihachi drinks too much, staying away from work. When his son discovers what is happening, he confronts his father, and the two have it out. Unfortunately, their reconciliation has unforeseen consequences and Tomio gets sick. This event changes everyone's course, and it forces Kihachi to get his act together and show his true colors. The poverty-stricken man's stubborn pride gives Ozu yet another opportunity to question the honor of social mores and make a comment about community.

Shooting in the slums where Kihachi and Tomio rest their heads, Ozu and cinematographer Shojiro Sugimoto make the most of their cramped settings, often crowding their actors in the frame. The lives of the working class were seen as something to escape, and just like the parents in I Was Born, But..., Kihachi only wants to see his son better him. He is bemusedly aware that the boy has already done so, and this convention of the child being more responsible than the father is one that survives in movies and television to this day. Kihachi himself would also survive, with Sakamoto returning to the role several more times, including in Ozu's breakthrough A Story of Floating Weeds the following year. The director saw the potential in the character as a means of expression, reflecting many of the patriarch's in the filmmaker's own life. As such, that depth and charisma is already on display in Passing Fancy on both comedic and emotional levels.

All the movies have the same audio options: either a truly silent version or an optional mono score by Donald Soshin. You will be asked to "activate" the score from the main menu. Soshin's music fits the mood of each movie well without being overbearing or obtrusive. He writes for the piano, and he knows when to be softer (Tokyo Chorus) or more light-hearted (I Was Born, But...). His work is elegant and right on, servicing the material without advertising itself.

The intertitles on the films are in Japanese, with optional subtitle translations. These English titles also serve to translate important signs and other pieces of writing in the movies. I particularly liked the little boy in I Was Born, But... with the note on his back that read, "Upset Tummy, Do Not Feed Him Anything."

Part of the fun of studying cinema history is to look back over a career and see the building blocks that allowed great directors to put together their signature style. Working in his second decade as a filmmaker and holding off transitioning to talkies until he got silent movies just right, the Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu found his most commonly traveled ground in three bittersweet, good-hearted family stories. Made from 1931 to 1933, the trio that makes up Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies - Eclipse Series 10 serves as a welcome introduction to the great artist's work. Full of comedy and pathos, these wonderful stories of generational gaps and social struggles remind us that good drama and honest writing supercedes any technological advancement as the most essential tools in filmmaking. Another solid hit for Eclipse.

For technical specs and special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

This DVD set will be released on April 22, 2008.

Friday, April 11, 2008

4 X AGNES VARDA (#418): LE BONHEUR - #420

It’s funny that I ended my previous review of Agnès Varda’s Le Pointe Courte with the lines, “Happiness isn’t so easy to come by, and if it wasn’t work, it wouldn’t be worth it,” because her 1964 film Le Bonheur, which translates as “Happiness,” seemingly tells us something entirely different.

Opening on an idyllic spring day, Le Bonheur shows us a French nuclear family enjoying a picnic in the woods. Handsome papa Francois (Jean-Claude Drouot) dotes on lovely mama Therese (Claire Drouot), and they both show genuine affection for their children Gisou and Pierrot (Sandrine and Olivier Drouot). It’s a perfect scene, almost tailor-made for the movies. In fact, when they return home, Francois’ brother and his wife are watching a similar scene on TV, though even the small clip we see should be enough to suggest to us that something is not quite right. Why has Varda chosen a scene from Jean Renoir’s Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe (Picnic on the Grass) where, apparently, an older man schools a younger woman on the ways of the world? And was it by accident that the television it’s seen on appears to be practically two-dimensional? Is the world of cinema flat in comparison to our own?

Things go on pretty-good-sure-as-you’re-born for Francois and Therese. He works in carpentry with his brother, and the older sibling is looking to retire and Francois will take over. Therese stays home and sews dresses on the side, her two very well behaved children entertaining themselves in the yard. The married couple even has an active love life. From our outsider’s perspective, there is nothing amiss. Theirs is a good marriage, and they are good people.

So, why the wandering eye, Francois? When Emilie (Marie France Boyer), the pretty girl at the post office, flirts with him, Francois flirts back. Innocent enough on the first time, but the second time, it’s clear Francois was prepared to flirt before he walked through the door. He takes Emilie to coffee on her lunchbreak, they enjoy each other’s company, and they make a pseudo-date for Saturday when Francois is to come over to her apartment and fix her shelves. Francois doesn’t even have to be dishonest with her--he tells her more than once how he does not lie--and she knows he is married with kids. This guy has some game going.

Varda cunningly plays with her audience’s expectations in her set-up here. Raised on melodrama, most moviegoers will be waiting for the other shoe to drop. Francois has to cross a line somewhere, doesn’t he? He has to do something to make us hate him. Yet, he somehow manages to skirt over the thinnest of ice and come out unharmed. Even his precious honesty manages to stay intact. Sure, his speech to his co-workers about how he believes in fidelity has ironic flourishes for us, knowing what we know, but if you really listen, his definition of fidelity is such that his conscience can remain clear. He says when he loves a woman, he sticks to it, and he doesn’t act capriciously. He doesn’t say he has to limit himself to just one partner, that’s just what his friends assume.

Francois tells a similar sort-of truth to go see Emilie on that first date. He tells Therese that he has taken on a job, and though he is hoping for more, at that point in time, that’s exactly what the meeting with Emilie is supposed to be. There is further irony to be had, though, in the fact that the appointment he can’t make with Therese is to accompany her to a wedding they have been invited to. She has helped the young bride with a gown emergency in record time, and they have been asked along to see her handiwork. On the same day Therese has made another woman’s connubial bliss possible, her trust in her husband could be causing her own to shatter.

I know this all sounds terribly heavy, but what you must realize is that all through this, Le Bonheur is light and airy. Varda has made a masterwork of tone, creating neither a comedy nor a drama, but something strangely other. Her sets are full of wonderful colors, lots of pastels and warm hues, everything bright and happy. Having started her career as a photographer, the writer/director has a stunning eye for detail. She is going to pack her frame with those details and show us each and every one. A flower, a necklace, a poster on the wall--everything contributes to this portrayal of the life Francois lives as being a miraculous thing. On his coffee date with Emilie, they are flanked by store signs that say “Temptation” and “Mystery,” and he also sees a giant billboard that declares quite plainly in black-and-white, “Love.” It’s as if all of society has gotten together to make this guy as happy as he can possibly be. All darkness has been banished. Even the fades between scenes are blue, red, or an autumnal gold rather than the usual black.

It’s the filmmaker working as seducer, and while her onscreen Don Juan casts his spell on his women, so too does Varda use her filmmaking technique to capture us in that spell. When Francois explains to Emilie how he can love her and his wife and how the two need not compete, it’s clearly a selfish philosophy meant to please only him, but since Emilie swallows it without much question, we start to think that maybe this guy has his finger on something. It’s those dang details. We’re so busy soaking in them, we don’t realize that that indefinable tone of Le Bonheur is slowly slipping into dark satire.

Francois finally comes clean to Emilie on another day out at the lake. Once again, he is in a position of having to defend his choices. He told Emilie that being with her made him feel more like himself, comparing her to wildflowers while his wife is something more sturdy and reliable. Then, among the wildflowers, he tells the sturdy and reliable Therese that if this extra-marital love makes him happier, he can then turn around and make her happier. Remarkably, this seems reasonable to her, and I don’t know that it necessarily sounded reasonable to me, but I was at least impressed that once again Francois got away with it. Maybe there is something to this “European morality” after all.

Except, no, here is where Varda unveils a shocking development. Francois’ selfishness does have its consequences. After telling Therese that being untrue makes the truth all the more clear, the couple makes love and, predictably, the man falls asleep, right there under the tree, the solid alternative to the fragile and finite flower. The children wake before Francois does, and they want to know where mommy is. She has disappeared!

I knew right away what had happened. For all her toying with our expectations, there are certain things that Varda can’t mess with, we know it in our bones. There have probably been whole books written on the Ophelia motif in art and literature. There is even this one

Le Bonheur is probably too early to be seen as a critique of the free-love generation, but Varda is definitely questioning what it means to be happy in a relationship in a modern media-savvy world. Francois has a very traditional life, and he wants for nothing. He has no desire to leave Therese and the kids, he’s content. (How weird, too, that this apparently was a real-life family cast in the film!) He also loves Emilie. He’s living by the “if it feels good, do it” credo. By being part of that traditional model, Therese is forced to represent traditional values. She’ll do anything to make her husband happy, including allowing him to have another lover. Her choice to throw herself in the river is motivated by reasons only known for sure to her, but there are many lines of debate. I would probably lean away from it being that she can’t be happy and make him happy at the same time and so chooses suicide rather than share him--though there is plenty of literary evidence to suggest that women choose water as their exit because for them life is overwhelming, suffocating, and, when you’ve gone under, inescapable. (The best cinematic example of this has to be Julianne Moore’s bedridden flood in The Hours

Remember that line I was waiting for Francois to cross? Well, here he crossed it. Now is the time to start hating him. He spends the summer mourning the loss of his wife, but by fall, he’s ready to move on. Though he did indulge in a gruesome daydream where he saw Therese flailing to escape the water, even that is just to assuage any guilt. Of course he’d imagine her as not wanting to die! Seeing no reason to give up Emilie, he instead swallows her whole, promoting her to wife and mother. The flower that was once praised for growing free is now plucked and replanted where Francois can always admire it. The film ends where it began, once more out in the sunny climes of nature, the man and his new wife wearing matching sweaters, a slightly burnt yellow that mimics the changing flora. They have become their own advertisement. Life goes on when you’re happy.

I can’t help but wonder about Emilie, though. One thing she said keeps ringing in my head. When she first sees Francois after Therese’s death, she tells him, “I am happy and I am unhappy.” It’s a fairly honest statement. She can’t be pleased that a woman is dead even if it does mean it clears the way for her to be with Francois. These are famous last words if ever I heard them. When Francois makes his pitch for their new life, Emilie agrees in word, but her face and body language aren’t 100% behind the capitulation. She’s only doing what she has to do to be with the man she loves, and though making him happy makes her happy, it’s always going to be at the expense of her own full and complete bliss.

Thursday, April 10, 2008

4 X AGNES VARDA (#418): LA POINTE COURTE - #419

"I came to make noise, but silence has won out."

Agnès Varda is one of the less celebrated directors working amidst the French New Wave, always seeming just a little bit outside of the irascible boys club that sprang out of Cahiers du cinema. I get the sense, though, that this may be how she wanted it to a degree. Though I haven't seen a ton of her films, the ones I have seem strike me as being more about observation, about a certain separateness. The director making the film likes to watch, to chronicle, and I imagine her as someone who was always there, maybe not as prolific as Truffaut or Godard, but never absent nonetheless.

Her first film, La Pointe Courte, part of the 4 X Agnès Varda boxed set, actually predates the Nouvelle Vague by many years. Made in 1954, one could argue for it as the clear link between the French troublemakers and the Italian Neorealists who inspired them. Though the film is sold on the relationship element, the troubled marriage that is the hook of the film--its two participants, Silvia Monfort and Philippe Noiret, are the faces on the DVD cover--it's about much more than that, and I wouldn't argue with you if you said Varda had used the couple as an excuse to shoot the La Pointe Courte fishing village, that it was the people working the lagoon that really interested her. Indeed, the credits even say as much, with the auteur sharing writing credit with the citizens of La Pointe.

In fact, it takes us a long time to see the husband and wife, and even when we do, they spend their first scene with their backs to the audience. The first several minutes of the movie instead are spent establishing the difficult conflict of the fishermen. Their waters have been semi-quarantined due to allegations of contamination. They know the shellfish they harvest are not bad enough to be causing bodies to pile up, so they go ahead and fish anyway, their survival taking precedence over the slowly unwinding red tape that is trying to sort out whatever the problem may be. The early scenes in the film show how three generations of one family live on the same land, in interconnecting houses, and work together to throw the government off of their seaside scent when Grandpa is spotted in forbidden waters.

Varda and cameramen Paul Soulignac and Louis Stein move freely through these buildings, uninhibited by walls or even their equipment, capturing a sleeping cat here, a pile of shells there. The look is documentary, but the way the cameras fly over the landscape is almost epic, a working man's David Lean shooting on DV. Like De Sica, Varda is seeking the visual poetry of real life. The burly fisherman and their equally burly wives and daughters, the single mother with seven children by multiple men, the trash and debris scattered around an impoverished homestead--these are meals gobbled up by the hungry lenses.

La Pointe Courte isn't just a random setting, however, it's also a metaphor for that footnote of a relationship. Just as some unknown rancor has tainted the waters, the marriage between Elle (Monfort) and Lui (Noiret) also has something rancid under the surface that they are trying to uncover. They know they are unhappy, but the tests haven't been run to pinpoint exactly what is making them so. Lui grew up at La Pointe, and so he has devised a plan to leave the hustle and bustle of Paris and get back to the simple life of his hometown. It's a forced nostalgia for supposedly better times, and maybe if he can recapture his childhood, he can also rediscover the salad days of early wedded life from five years before. There have also been five days that he has waited for Elle to join him there, every morning going to the train station to see if his spouse is a new arrival. It's a romantic gesture, but futile in its way, just fumbling in the dark.

The way the couple walks the countryside, discussing their fracture, reminds me of the early '60s films of Michelangelo Antonioni. There is also something of the endless discussions in Alain Resnais' breakthrough films, and not for nothing is Resnais one of the credited editors on La Pointe Courte. The way the mis-en-scene moves us through the rundown shacks of the village is like a Bizarro version of the similar tours of grand mansions in Last Year at Marienbad. The interesting contrast comes in the fact that for as natural as the footage of the fishermen feels, the stuff with the couple is stagy and heavily directed. They stare in the camera, framed by their surroundings and by the screen, speaking in poetic musings in direct juxtaposition to the less mannered dialogue of the workers. Even the subtitles reflect this, with dropped consonants and slang showing the less erudite speech patterns of the regular folks. In fact, the townspeople think their visitors' main problem is they talk too much, and listening to their conversation go in ever-widening circles until they finally exhaust themselves, this theory appears to not be entirely wrong. Likewise, Elle and Lui can't merely walk somewhere, they are always entering a landscape, always creating a shot. Note how many times a train of some kind forces them to wait to cross its tracks, cutting them off from their destination the way Elle's not-taken trip had separated them for the previous week, the way their falling out of love splits them now.

"Nature separates us," Elle says at one point. She means that if a man and a woman come together and they really aren't meant to be, the time and tide of life will push them apart, but she's really summing up everything about La Pointe Courte, isn't she? Style, fashion, the way of filming--this separates the couple from reality (just as it separated Hollywood convention from burgeoning international cinema). The pair couldn't be farther apart from the fishermen even when they are standing amongst them. It's this distance that has put the lovers where they are, they've lost sight of what's important. What are their petty problems next to the greater struggle for survival, the food chain, a dead child?

Yet, there is also hope to be had. Despite Lui and his lingering doubts, La Pointe works its charms on Elle. She finds peace in the unadorned existence of its people. The lesson she learns is that love is not about the passion of first romance, just as living isn't about the idylls of childhood or a day is not about the sunset that starts it. Sure, you can know that a better lagoon is just beyond a certain point, and that's where the best fish are, but just because you can't get there yet doesn't mean you shouldn't make do. Don't ever stop striving, but also don't strive at the expense of what is in front of you. Happiness isn't so easy to come by, and if it wasn't work, it wouldn't be worth it.

Agnès Varda is one of the less celebrated directors working amidst the French New Wave, always seeming just a little bit outside of the irascible boys club that sprang out of Cahiers du cinema. I get the sense, though, that this may be how she wanted it to a degree. Though I haven't seen a ton of her films, the ones I have seem strike me as being more about observation, about a certain separateness. The director making the film likes to watch, to chronicle, and I imagine her as someone who was always there, maybe not as prolific as Truffaut or Godard, but never absent nonetheless.

Her first film, La Pointe Courte, part of the 4 X Agnès Varda boxed set, actually predates the Nouvelle Vague by many years. Made in 1954, one could argue for it as the clear link between the French troublemakers and the Italian Neorealists who inspired them. Though the film is sold on the relationship element, the troubled marriage that is the hook of the film--its two participants, Silvia Monfort and Philippe Noiret, are the faces on the DVD cover--it's about much more than that, and I wouldn't argue with you if you said Varda had used the couple as an excuse to shoot the La Pointe Courte fishing village, that it was the people working the lagoon that really interested her. Indeed, the credits even say as much, with the auteur sharing writing credit with the citizens of La Pointe.

In fact, it takes us a long time to see the husband and wife, and even when we do, they spend their first scene with their backs to the audience. The first several minutes of the movie instead are spent establishing the difficult conflict of the fishermen. Their waters have been semi-quarantined due to allegations of contamination. They know the shellfish they harvest are not bad enough to be causing bodies to pile up, so they go ahead and fish anyway, their survival taking precedence over the slowly unwinding red tape that is trying to sort out whatever the problem may be. The early scenes in the film show how three generations of one family live on the same land, in interconnecting houses, and work together to throw the government off of their seaside scent when Grandpa is spotted in forbidden waters.

Varda and cameramen Paul Soulignac and Louis Stein move freely through these buildings, uninhibited by walls or even their equipment, capturing a sleeping cat here, a pile of shells there. The look is documentary, but the way the cameras fly over the landscape is almost epic, a working man's David Lean shooting on DV. Like De Sica, Varda is seeking the visual poetry of real life. The burly fisherman and their equally burly wives and daughters, the single mother with seven children by multiple men, the trash and debris scattered around an impoverished homestead--these are meals gobbled up by the hungry lenses.

La Pointe Courte isn't just a random setting, however, it's also a metaphor for that footnote of a relationship. Just as some unknown rancor has tainted the waters, the marriage between Elle (Monfort) and Lui (Noiret) also has something rancid under the surface that they are trying to uncover. They know they are unhappy, but the tests haven't been run to pinpoint exactly what is making them so. Lui grew up at La Pointe, and so he has devised a plan to leave the hustle and bustle of Paris and get back to the simple life of his hometown. It's a forced nostalgia for supposedly better times, and maybe if he can recapture his childhood, he can also rediscover the salad days of early wedded life from five years before. There have also been five days that he has waited for Elle to join him there, every morning going to the train station to see if his spouse is a new arrival. It's a romantic gesture, but futile in its way, just fumbling in the dark.

The way the couple walks the countryside, discussing their fracture, reminds me of the early '60s films of Michelangelo Antonioni. There is also something of the endless discussions in Alain Resnais' breakthrough films, and not for nothing is Resnais one of the credited editors on La Pointe Courte. The way the mis-en-scene moves us through the rundown shacks of the village is like a Bizarro version of the similar tours of grand mansions in Last Year at Marienbad. The interesting contrast comes in the fact that for as natural as the footage of the fishermen feels, the stuff with the couple is stagy and heavily directed. They stare in the camera, framed by their surroundings and by the screen, speaking in poetic musings in direct juxtaposition to the less mannered dialogue of the workers. Even the subtitles reflect this, with dropped consonants and slang showing the less erudite speech patterns of the regular folks. In fact, the townspeople think their visitors' main problem is they talk too much, and listening to their conversation go in ever-widening circles until they finally exhaust themselves, this theory appears to not be entirely wrong. Likewise, Elle and Lui can't merely walk somewhere, they are always entering a landscape, always creating a shot. Note how many times a train of some kind forces them to wait to cross its tracks, cutting them off from their destination the way Elle's not-taken trip had separated them for the previous week, the way their falling out of love splits them now.

"Nature separates us," Elle says at one point. She means that if a man and a woman come together and they really aren't meant to be, the time and tide of life will push them apart, but she's really summing up everything about La Pointe Courte, isn't she? Style, fashion, the way of filming--this separates the couple from reality (just as it separated Hollywood convention from burgeoning international cinema). The pair couldn't be farther apart from the fishermen even when they are standing amongst them. It's this distance that has put the lovers where they are, they've lost sight of what's important. What are their petty problems next to the greater struggle for survival, the food chain, a dead child?

Yet, there is also hope to be had. Despite Lui and his lingering doubts, La Pointe works its charms on Elle. She finds peace in the unadorned existence of its people. The lesson she learns is that love is not about the passion of first romance, just as living isn't about the idylls of childhood or a day is not about the sunset that starts it. Sure, you can know that a better lagoon is just beyond a certain point, and that's where the best fish are, but just because you can't get there yet doesn't mean you shouldn't make do. Don't ever stop striving, but also don't strive at the expense of what is in front of you. Happiness isn't so easy to come by, and if it wasn't work, it wouldn't be worth it.

Wednesday, April 2, 2008

JULES DASSIN: RIFIFI - #115

Jules Dassin died earlier this week at the age of 96. The ink was barely dry on my tribute to Richard Widmark, and two days later the actor's Night & the City director passed away. Both had lived a long, long time, but it doesn't quell the suspicion that the world is cruel and indifferent after all. The universe has no need for these connections, it takes from us what it wants. In fact, I am even more shocked to learn from the Criterion blog's obituary for Dassin that Malvin Wald, screenwriter on The Naked City, also died earlier this year. It's like all of the voices that were part of these great films are going silent.

Dassin is an interesting person, equally as interesting as any of the characters in his films. He knew a little bit about the indifference of the universe, and despite being an expert purveyor of the cruel worldview of film noir, he never was a fellow to let things beat him. He had already made several classic genre films when Daryl F. Zanuck sent him overseas in 1950. On paper, it was to make Night & the City, but in reality, Dassin was being sold out to HUAC by fellow directors Edward Dmytryk and Frank Tuttle and was being shipped out before scumbag Joe McCarthy could rake him over the coals for alleged connections to the communist party. The down-and-out urgency and paranoia of Richard Widmark on the run in Night must have had an eerie familiarity for Dassin. In many ways, the world really was against him, and the outsider community he was a part of (Hollywood) was betraying him. Well, everyone but Zanuck, who at least tried.

Five years would pass between Night & the City and 1955's Rififi. For all the wonderful culture France has given to the world, including cinematic greats like Renoir, Godard, and Truffaut, how funny that the quintessential film from their noir catalogue was made by a Russian Jew ex-pat from Connecticut.

Rififi is the story of Tony le Stephanois, played with hangdog fatalism by Jean Servais, probably best known to American audiences for his small role in The Longest Day

Knowing he is at the end of the road, Tony wants one last score. When asked what he will do with his take of the jewels, he confesses to having no idea. Given that he may not have that long to actually ponder the situation, this would lead us to believe that the robbery is more about the action, of doing something to prove that he can. He originally refused to be a part of a smash-and-grab job, but after it's clear Mado is no longer his, he throws in with the other guys only after upping the plan to a full-on heist. Certainly that has to count for something. The meeting with Mado is the most brutal scene in the film, with Tony taking a strap to her and marking her before sending her back to her new boyfriend. Dassin treads that line of showing a bad dude for what he really is, even as he is the de facto hero of Rififi. But then, that's what the title refers to, a slang term for the rough business that tough guys get into. In a memorable scene at the L'Age d'Or, the nightclub's singer (Magali Noël) performs a ballad that both explains and glorifies the lifestyle, laying bare the filthy business while also romanticizing its kinky thrills.

(Sorry, I couldn't find it subtitled.)

The scene between Tony and Mado is also an occasion to illustrate Tony's shift to the other side of life. As the violence explodes, the couple moves off screen while Dassin's camera goes in the opposite direction, zooming in on a photo of days gone by, of the lovers enjoying champagne long before this dirty business separated them. Like a standard noir anti-hero, Tony is cut off from his past even as it continues to dog him. The future is also beyond him, as represented by the godson, Tonio (Dominique Morin), who is named for the gangster. Little Tony represents the hope of the future, of having the option to be whoever he will be. Big Tony is already who he is, he can be nothing else. All he has then, is the present. Do what can be done now, cry about what is lost to you some other time.

That present makes the creamy filling of Rififi. The late-night robbery of the jewelry store is a stunning sequence. Shown in meticulous detail, and in absolute silence--no speaking, no music, only the ambient noise of the thievery--it is a truly genius exercise in story and style. If your concentration breaks during this portion of Rififi and you actually become aware that you are watching a DVD, check yourself. You're probably inhaling, as you almost literally are coming up for air, having been holding your breath to see if the guys succeed. Your heart will be in your throat when they crank their tools to break through the back of the safe, believe me. It's such an impressive sequence, Jean-Pierre Melville practically lifted the idea wholesale for his 1970 heist picture Le cercle rouge.

Knocking over the jewelry store is not the finale of the film, it's more like the fulcrum. From there, wheels are tipped and come rolling down to push Tony and his gang toward their final fate. This is noir at its finest, grisly and unforgiving. There is no escaping one's past, and there is no stopping the oncoming future.

And yet, this certainly can't be Jules Dassin's point of view. If it was, it was temporary, as he was only a couple of years away from meeting the love of his life, Melina Mercouri, the star of his international hit Never on Sunday

This makes it all the more fitting that Dassin cast himself as the ladies man Cesar le Milanais in Rififi. Crediting himself as Perlo Vita, Dassin played the most light-hearted character in the movie, a clotheshorse who enjoyed the finer things. As the safecracker, Cesar was the essential component of the job, and much like a film director, the one who breaks through to the good stuff. There is also some irony that it's Cesar who sells his fellows out to their enemies. When Tony finds him tied up at the L'Age d'Or, he asks the Milanais why he turned rat. Cesar replies that he was scared, he had to. Coldly, Tony informs the turncoat that he regrets having to do what he's going to do, but Cesar knew the consequences when he chose to break the rules. In an existential noir world, the rules are everything. Cesar is gunned down for not being able to keep his mouth shut.

As Issa Clubb mentions in her piece on the Criterion blog, talking ill of others was something that Dassin never did, not even about people whose past misdeeds left them open to being publicly vilified. It was done to him, and he would never do it to anyone else. That was his code, and another in the long list of reasons why the man deserves our lingering respect.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)