"

I live now in a world of phantoms, a prisoner of my own dreams."

Ingmar Bergman's 1957 Swedish production

The Seventh Seal is the poster child for foreign films. It more than any other movie is what the average person thinks of when they think European cinema, and it's the first one other filmmakers go to when they want to make a parody of pretentious, depressing art house flicks. The most obvious and extended lampoon that comes to mind for me is

the second Bill and Ted movie, though I think one of the more recent examples of someone using

The Seventh Seal is Stephen Colbert's fake health segments,

"Cheating Death," on

The Colbert Report. The intro to those pieces shows Colbert playing a chess game with the Grim Reaper, which is the standard image, and by its ubiquity, you'd think that it was a far more substantial part of the movie. The actual chess game begins in the first two minutes of the picture, and it comes up twice more, yet is finished by the climax of the movie. I suppose this speaks to the power of the image that Bergman created that half a century later all you have to do is say "chess game with Death" and most people will immediately think of

The Seventh Seal, whether they know that's what they are thinking of or not.

There are a number of things that are sad about the fact that a large segment of the population is scared of foreign films, but the misconceptions about what

The Seventh Seal is supposed to represent is pretty high on the list. As a viewer, I wouldn't blame you for going into the movie thinking it is going to be pretentious and depressing, that the criticism inherent in the parodies is right; coming out of it, however, you'll probably be surprised by how far from the truth it all is.

The Seventh Seal isn't a work so shallow that it can be deconstructed in a single perfume commercial, nor is it a film so self-involved as to make the mind feel pained or bloated, like you'll survive its 97 minutes but feel like you've been engorged. The surprising thing about

The Seventh Seal is how light it really is. Yes, it deals with some important subjects--faith and doubt, mortality, religion, compassion--but it's never burdensome, never pushy. Rather, Bergman's script is so well constructed and his themes so expertly integrated into the overall narrative, the philosophizing never overtakes the story, and there is never a scene where the momentum of the action is lost amongst heady exposition. Nor is it an overly serious affair. Rather,

The Seventh Seal is regularly funny, sometimes lusty, and often touching.

The Seventh Seal is set in medieval times, amidst plague and Christian crusades, both of which contribute to an overwhelming pallor of death that is permeating the land. Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) and Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand), a knight and his squire, have just returned from ten years fighting the heathens in Africa. Their spirit is broken, their eyes opened by what they have seen. Jöns is more practical about it, life is what it is and one just carries on, but Antonius is in the midst of an existential crisis. His relationship with God is suffering from a sense of abandonment that is about to give way to not believing in a Supreme Being at all, and he is desiring of some proof that all of this fighting has not been in vain. So much so, that at the outset of the picture, when Death (Bengt Ekerot) comes to claim his immortal soul, Antonius stalls him with that famous chess game, saying he has something he needs to do before he can shuffle off this mortal coil. On the surface of it, that task appears to be returning home to his wife, but this is more Odysseus by way of Camus and that goal is really more of a red herring. It's more like returning to the source of his belief to see if it's still there.

Perhaps this is why he takes the acrobat family under his protection, he sees something in their unit that reminds him of why he wanted to side with the good and not the bad. In particular, he admires the forthright and caring nature of Mia (Bergman-regular Bibi Andersson), who cares both for her flighty husband, Jof (Nils Poppe), and their one-year-old baby. Mia is down to earth and practical, though practical in a common-sense way, still open to experience, and not as cynical as Jöns. You could even argue that the woman and the squire represent two sides of Antonius' conscience, one imploring him to remain open to life and the other suggesting he close up and wait it out. At the same time, Jöns also provides the example for personal redemption by saving the unnamed girl (Gunnel Lindblom) from the corpse-robbing rapist, Raval (Bertil Anderberg)--though Jöns' insistence that the girl serve him in return shows how badly mangled his sense of Christian charity has become now that he has rejected the church. Then again, there is also no more potent symbol than the attacker, in that Raval is the one who convinced Antonius and Jöns to join the Crusades a decade ago. The man who sent believers off to their death is now picking over their bodies.

Bergman provides many examples of how topsy-turvy the world is. The second scene of the movie, right after the knight meets and challenges death, is our introduction to the performance troupe that Mia and Jof are a part of, and their third partner, Skat (Erik Strandmark), emerges from their trailer wearing a Death mask. They are on their way to a religious festival. The monks running it have hired them to perform a play that will scare the audience into repenting, propaganda along the lines that the plague is punishment against sinners. The current prevailing message of the Church is that doom is the only possible reward anyone can hope for, and they will scare you into accepting or burn you at the stake (which we see, actually, when they fry a young "witch" (Maud Hansson) for not getting on board). Hordes of religious thugs are as pervasive as the disease they claim to fight, and this seems like the wrong kind of salvation to the returning warriors. Antonius and Jöns have become symbols for life themselves, the death bringers now challenging the end of all things and offering sanctuary to the tormented, whereas by taking the job at the festival, the entertainers, whose job it is to lighten people's loads, are now the ones piling on the gloom.

The plague state is akin to an apocalyptic nightmare, and so imagery in

The Seventh Seal resembles the end of days. From the corpse that Antonius and Jöns find in the road--and whom the squire amusingly seeks directions from; his speech after the fact is one of his many funny chunks of dialogue--through the hooded monks who so resemble Death that after Antonius accidentally gives confession to a disguised Reaper you're never quite sure where he'll pop up again, to the knight's isolated castle, there is a sense that everything is being laid to waste. When Raval catches up with the caravan 2/3 in--the way characters enter and exit in

The Seventh Seal are a tell-tale sign of its theatrical roots--on his last legs, having caught the plague himself, it suddenly seems that they are all merely staying one step ahead of the devastation the way Antonius is managing to stay one step ahead of Death. The world they have left has ceased to exist.

Bergman is aware of how thick he is laying it on, and there are a couple of self-reflexive moments where the author lets us know the potential for misunderstanding and parody is not lost to him. Some of the things the acrobats say about what audiences will sit through are like a wink forward to the critics who would say similar things about

The Seventh Seal. The artist played by Gunnar Olsson, whom Jöns meets early in the picture, the painter who is creating a mural about death, even says that sometimes the common man needs to have a little depression foisted upon him so he will consider serious things, as if the director of

Smiles of a Summer Night was worried he'd have to explain to a bewildered public where all the fun had gone. That same artist also admits that when the money runs out, he will paint the more sunny subjects that people pay for, a sly explanation of the trade-off pattern of tragedies and comedies that Bergman would make in the 1950s and '60s. One for me, one for them. Though, it's also a ratio existent in

The Seventh Seal. It's a comic tragedy, or a tragic comedy. How else do you explain the subplot of the blacksmith (Ake Fridell) and his wife (Inga Gill), who runs off with Skat and then weasels her way back into her husband's good graces when caught? Jöns provides a running commentary on women, stoking the blacksmith's flames of anger the way Groucho might ignite the ire of one of the other Marx boys. And when Skat gets his, set upon by a gleeful Death, it's probably the funniest scene in the whole movie. No reason a guy can't go out laughing, is there?

These moments of laughter greatly offset Antonius' existential emptiness. He is a forebear of the 20th-century man seeking some kind of sense in a senseless world. He is not ready to admit that his beliefs are gone, so much so that his main gambit in the chess game, a combined knight-bishop attack, symbolically represents how he has always seen the world as being governed. At one point, he states his own fundamental problem, saying, "Faith is a heavy burden, you know? It's like loving someone out in the darkness who never comes no matter how loud you call." In the same conversation, shared with Mia, he refers to a betrothed that he lost, and if we read between the lines, he's referring to Jesus, once again indicating that his homeland mission is not all it seems. At the witch burning, the knight is juxtaposed with the accused, and he wants to know how she can retain her belief on the way to the pyre. She sees what is not there and trusts that it will carry her through, whereas he desires something tangible, something he can put his hands on. Overhearing all this, a ghastly looking monk asks him, "Do you never stop asking questions?" and when Antonius confirms that he does not, the monk lays him low with the futility of his plight: "You get no answers."

Placed against the unknowable, the simple pleasures of life with the acrobats, of playing with the baby and eating wild strawberries, is its own kind of paradise. The fact that they can have such tiny joys, or that the blacksmith can get so worked up about his wife's wanton ways, means that petty human drama is still important. That's the scintilla of hope, the last refuge in a meaningless wasteland, the thing one would hang onto in a post-apocalyptic world: the ability for man to continue. Even when others behave like beasts, be it the cruelty they inflict on Jof or Skat rutting with the blacksmith's wife, quite purposely scored by Mia and Jof singing a song about animal behavior, there is still the sustaining bond of mother and child. It's not for nothing that Mia and Jof in some translations are called Mary and Joseph, making their little Mikail the source of all tomorrows. (And, you know, you do kind of wonder how the lovely blonde ever got hooked up with the nerdy juggler. A virgin conception explains a lot.)

You can also see some remaining compassion in the girl that Jöns rescued. She silently watches everything, and she is the only one who is willing to help the disease-ridden Raval. Things reach their portentous apex around this time. In the forest, there is a point where everything goes quiet, where the world grows still. Bergman has used the natural landscape throughout

The Seventh Seal, even opening up on a raging sea, and so the sudden lull is a little chilling. Plus, as voiceover at the start of the movie and a prayer at the end informs us that, in the Book of Revelation, when the Seventh Seal is opened, leading the way to final judgment, the world does go quiet this way. Though Bergman is never heavy-handed enough to have any of his characters openly acknowledge this connection, they do mark the moment, and it does seal their fate. This and some cryptic remarks by Death make Antonius realize that the game has gotten larger than him, that more is at stake, and so he must take action to rescue those in his charge. That, too, is an existential solution: salivation in man's action. He has retained some of the compassion that the nameless girl sought to hang on to, and so it is also she who prepares them to accept what cannot be avoided. She is the first to move toward Death, to lead the way to eternal peace, repeating Christ's final line, "It is finished."

At the end of the film, only the actors are left alive, and Jof, who is prone to mystical visions, spots the lost group up on a hill with Death, a chain gang in service to the bitter end, engaged in what he sees as a kind of dance, a new troupe destined to put on a show for the ages. Another self-reflexive moment, to be sure. With the movie now ended, Bergman's own troupe is, in its way, now enslaved to perform this play over and over thanks to the Hell of Celluloid. It's also the dance of life, the endless performance of being amongst the waking world that we are all engaged in.

The final scene reminds me, as well, that I would be remiss were I not to consider the performances, because really, the actors play an essential role in keeping

The Seventh Seal from crumbling under the pressure of its own artistic aspirations. There is a convergence of styles here. Some of the comedy routines (as well as some of the music by Erik Nordgren) call to mind classic cinema traditions. The banter between Gunnar Björnstrand and Ake Fridell, the routines put on by Nils Poppe and Erik Strandmark--these polished performances appear so effortless, it is like watching the professional funnymen that moved from Vaudeville to Hollywood, like they've spent some time studying Abbot and Costello and the like. On the other hand, the more serious parts have a naturalism that is very much of the 1950s and the emergence of method acting and other less mannered styles. Max von Sydow is often called upon to play the creepy roles in horror movies, but his turn as Antonius Block has a thoughtful gravitas and a quiet nobility. When coupled with Bibi Andersson's earthy, unglamorous portrayal of Mia, Sydow also takes on calm and sweetness. Andersson is seductive without doing anything sexy. She is more sensual, a mother whose warm and open manner inspires a more primal desire. Given how gorgeous Andersson can be in movies that call for fancier dress, the "no make-up" look she wears in

The Seventh Seal is almost more glamorous by how rare and beautiful it is. Antonius even tells Mia, after seeing her for the first time off stage, that she looks better without "all that paint" on her face.

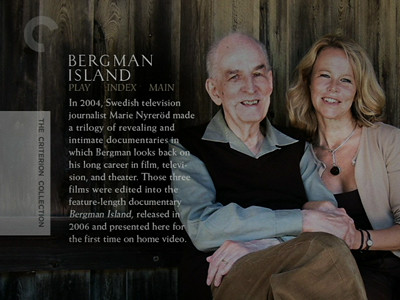

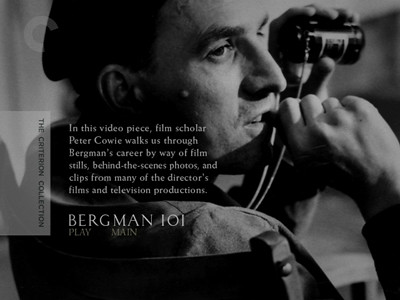

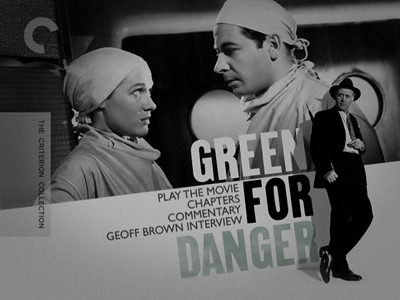

The new two-disc edition of

The Seventh Seal is the second that Criterion has released. It's been eleven years since that fist disc, and the decade of improved technology really shows. The new transfer is stunning, flawless, and whatever other superlative you care to toss at it. There are also a bunch of new extras--including the

Bergman Island bonus DVD--with my favorite being the short tribute Woody Allen put together for Turner Classic Movies. In it, Allen discusses why he likes Bergman, making the distinction between the perceived artistry and the inherent entertainment value in Bergman's films. He speaks of

The Seventh Seal as a suspense picture and a fairy tale.

It's too bad they couldn't also include Stephen Colbert's tribute to Bergman, made two years ago when the director passed away. I can't imagine Ingmar not smiling at the reverent irreverence of it.