Comics artist Jason Latour has given us a sneak at another of the posters for the Jim Jarmusch-curated All Tomorrow's Parties festival. This time for Peter Bogdanovich's The Last Picture Show.

Click on this thumbnail to go to Jason's blog and links to see it bigger:

And my entry on some of the other posters here.

Monday, August 30, 2010

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

I FIDANZATI - #195

Ermanno Olmi's 1962 drama I Fidanzati (The Fiancés) takes the cliché that long-distance relationships always fail and turns it around. The Italian writer/director explores how romance blossoms when his titular lovers are separated by work and then steps back to see if it can thrive under these unnatural conditions.

Carlo Cabrini plays Giovanni, a factory worker engaged to Liliana (Anna Canzi). We meet them on a night out in Milan, their hometown. They have gone out dancing, but they are in the middle of a fight. Giovanni has been offered a promotion in Sicily, a step up he can't refuse no matter how much his fiancée wants him to. In these efficient and expertly edited opening scenes, Olmi sets up the style of I Fidanzati. The conflict isn't expressed in the dialogue of the argument, but rather by jumping around in time, seeing Giovanni get the offer and how he breaks the news to Liliana. This is how the whole film is told, as a jumble of memory. Though there is one thread that goes through I Fidanzati, Olmi shows us how the past causes tremors in the present, how a tweak on one end of that story line can cause vibrations further down.

Giovanni moves to Sicily and starts his new job. He gets a room first in a hotel and then in a boarding house. He meets co-workers who are also transplants, and he travels the town to see how the locals live, including visiting the outlying farms and also the church. Life is familiar, but different. He is an outsider, and he never quite fits in. Even the punishing weather reminds him that this is not home. It's hotter than he is used to, the torrential gales more dangerous.

I Fidanzati is a portrait of loneliness. Giovanni wanders his new digs as a man apart. His melancholy stirs up more memories, including ones that aren't so good, when he treated Liliana poorly. Olmi draws a subtle parallel between Giovanni's plight and his elderly father, whom he placed in a nursing home before departing. The caretakers tell Giovanni that life will be good for his father, but the old guys tend to have a hard time adjusting to being left on their own this way. They feel abandoned, and if they don't adjust, they waste away. Now that he is in exile, Giovanni could suffer the same fate. Eventually, letters from Liliana become his lifeline, and they grow closer via the openness of this new communication. Liliana even sees the irony--when they were together, they didn't talk nearly as much.

It would be easy for all of this to become a jumble, but Olmi and his champion editor, Carla Colombo, keep it well organized and never lose the viewer in the nostalgia and longing. Part of the clarity comes from the simplicity of Lamberto Caimi's camerawork. As with Il Posto [review], he and Olmi adopt a Neorealist style, avoiding any sweeping movements or camera tricks. Giovanni's tour of Sicily looks more like a documentary than a fictional film, and when he goes to a local festival, it's clear that this was a real celebration shot on location. The result is like the missing link between Fellini's big party in I Vitteloni and the carnival in Camus' Black Orpheus [review]. The realism keeps us grounded as the flashbacks grow dreamier. A scandalous trip to the beach is illuminated with idyllic sunlight, while the memories of early rendezvous with Liliana come quicker, like a greatest hits reel of young lovers.

Anyone worried that Olmi will betray this spartan aesthetic for the sparkle and suds of melodrama need not fear, I Fidanzati ends on an ambiguous note. The tone has grown optimistic, but when a phone call closes the gap in conversation, it adds a question mark. Are these two better when they have the postman between them? It's a question each viewer must answer for him or herself. As much as a I love the big embrace that comes at the end of many a classic Hollywood romance, push comes to shove, this is really how I prefer to see a love story conclude. Are you romantic enough to believe they will eventually get married and get on with their lives, or are you cynical enough to think they will only grow further apart?*

* Though I hadn't seen I Fidanzati when I wrote it, this was actually the intention of the finale of 12 Reasons Why I Love Her

Labels:

Ermanno Olmi,

fellini,

marcel camus,

my writing

SIDELINE: ALL TOMORROW'S PARTIES POSTERS

Criterion is taking part in the upcoming All Tomorrow's Parties festival, curated by none other than Jim Jarmusch. The esteemed filmmaker has put together a great line-up of films, and if you're anywhere near Monticello, New York, next weekend, you should go. Here are the details.

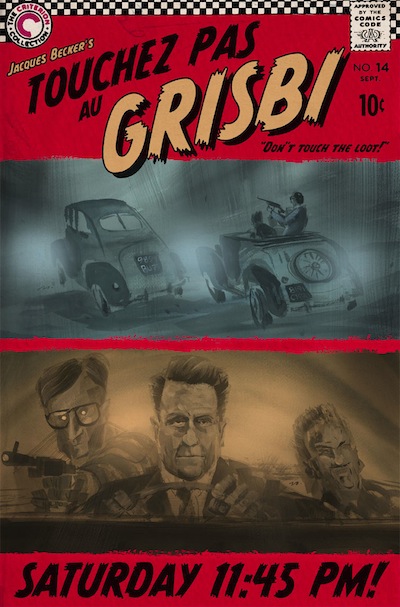

For the occasion, Criterion's designer Eric Skillman has commissioned a bunch of comic book artists to do new posters for films being shown.

Below are the ones released so far. I will update and repost as more come out. (For instance, I know Scott Campbell is cooking up something.) I will also recommend books by these fine fellows that I think will appeal to film fans. You really should check out their work.

* Matt Kindt

Night of the Hunter

Recommended Reading: Revolver , 3 Story: The Secret History of the Giant Man

, 3 Story: The Secret History of the Giant Man , Super Spy

, Super Spy

* Scott Morse

Brute Force [review]

Touchez pas au grisbi [review]

Check out Scott's other recent movie images, including 8 1/2 [review].

Recommended Reading: The Barefoot Serpent , Spaghetti Western

, Spaghetti Western , Volcanic Revolver

, Volcanic Revolver

For the occasion, Criterion's designer Eric Skillman has commissioned a bunch of comic book artists to do new posters for films being shown.

Below are the ones released so far. I will update and repost as more come out. (For instance, I know Scott Campbell is cooking up something.) I will also recommend books by these fine fellows that I think will appeal to film fans. You really should check out their work.

* Matt Kindt

Night of the Hunter

Recommended Reading: Revolver

* Scott Morse

Brute Force [review]

Touchez pas au grisbi [review]

Check out Scott's other recent movie images, including 8 1/2 [review].

Recommended Reading: The Barefoot Serpent

Labels:

All Tomorrow's Parties,

becker,

Criterion Art,

dassin,

fellini,

jarmusch,

robert mitchum

Monday, August 16, 2010

L'ENFANCE NUE - #534

Francois Fournier is a troubled ten-year-old who has been in foster care since his mother gave up on him when he was four. We don't know much about where he came from. Apparently his father was a miner, and from the one time Francois shares a memory of her, his mother sounds as if she is mentally ill. He has been listed as being in "temporary placement," ever since, meaning that his parents can come back for him any time. They never do. They barely even write.

This is the stage for French director Maurice Pialat's 1968 full-length debut, L'enfance nue (Naked Childhood). First-time actor Michel Terrazon plays Francois, a blank slate who says little, but does much. Though he is sweet deep down, Francois has a habit of acting out. He likes destroying things. We see him smash a watch and flush it down the toilet for no reason (he may have also stolen it). He drops his foster sister's cat down a stairwell just to show off. Is it any wonder that his current caretakers, Simone and Robby (Linda Gutemberg and Raoul Billerey), have had all they can stand?

So, Francois is bundled off to another family, an older couple named Thierry who have him call them Grandma and Grandpa (Marie-Louise and Rene Thierry). This is the second marriage for both of them, they both have kids from their previous unions, but since they were too old to have any together, they started taking in abandoned children. They are also caring for a very young girl and a high-school boy named Raoul (Henri Puff). Plus, Mrs. Thierry's mother (Marie Marc) lives with them.

We know all of these things about the Thierries because they tell Francois. All of them, including old Nana, aren't afraid to share their lives with this new house guest. Grandpa shows him photos from the war and medals he got fighting in the Resistance. Nana reads the funnies with him and tells him what words like "mistress" mean. Raoul gets him to open up briefly, but that's it. We end up knowing very little about Francois. His is a life we observe, we are not privy to what is inside him.

This is for a very good reason. L'enfance nue only gives us as much insight into Francois as he has in himself. Pialat has his young actor play the boy blankly because the character doesn't seem to know why he does what he does. Sometimes it's for fun, we might see him laugh or smirk, but other times, it appears to be habit and, often, impulse. In one scene, we watch him kick his shoe up the street, spot a storm drain, and then punt the shoe down it. Once it's gone, his demeanor immediately shifts. He did it deliberately, but he didn't consider what he would do once it was underground and in the muck. It's the kind of reaction someone has when they have issues with anger. In a rage, they punch the wall, and the pain and damage to the wall shocks them out of their fury; only here, it's something small and quiet yielding the same results.

The script for L'enfance nue is by Pialat and his regular collaborator Arlette Langman (they also made Loulou

Francois doesn't have that control. He is a ward of the state, subject to what social services dictates for him. He has no concept of being in charge, and his rebellion is limited to the confined space where they've exiled him. Like a prisoner, he does something, then drops the evidence, and waits to see if he's found out by the guards. It's not that he doesn't know how to act properly, either. He gives the first foster mother a gift when she sends him away, and he bonds with Nana, I just don't think he sees much benefit in maintaining. Not as long as he's "temporary."

And so L'enfance nue adopts this quasi-state. The story progresses, but almost imperceptibly. Change is identified by behavior, but Pialat never has anyone point it out. The most important development in Francois' personality is when, feeling guilty about stealing from Nana, he slips her coin purse back where he found it. (Though, a cynic might say he knew there was no way he would not get caught.) There is no epiphany that leads him to this, just as there is no a-ha moment to set the stage for the end. Things are what they are. Just watch.

The act of watching is rewarded in ways that exist beyond what is gathered from the story. L'enfance nue was shot by Claude Beausoleil, who also photographed Agnes Varda's Le bonheur [review]. Though L'enfance nue doesn't quite have the pastel color palette of the Varda film, which often looked like the characters were living in a magazine advert, Beausoleil still pays attention to the colors here. Walls tend to be painted in medicinal hues, like hospital-scrubs blue and toothpaste green. Most surfaces are flat, patterns only show up in the more inviting Thierry home, and the film has a sickly yellow tint that, though controversial, gives the version on this DVD L'enfance nue an unhealthy pallor and creates an overall aura of poverty. It's not quite Neorealism, but it's not exactly a Technicolor wonderland, either.

At the same time, the construction of the screenplay is like Neorealism. Pialat had been making short documentaries prior to L'enfance nue and his loose narrative owes more to that prior work experience than it does the Nouvelle Vague. As I said, this is a chronicle of a life observed, and so it's Pialat's intention to just hang back and let things happen. He doesn't enhance the emotions with music, nor does he write any big speeches for his characters. The script doesn't hand anything to the viewer or explain itself. You could conceivably sit through all of L'enfance nue and walk away empty handed. It's almost like a social experiment in that way. Are you someone who sees a displaced little boy like Francois and feels nothing, or are you someone who can become engrossed in another's sadness? L'enfance nue is a movie that requires empathy, not sympathy, and knowing the difference between the two is really all the difference in how it affects you.

That kind of empathy can also be found in Pialat's 1960 documentary short L'amour existe (Love Exists), included here as a thematic precursor to L'enfance nue. In this 20-minute piece, Pialat shows us the various states of life in the areas outside of Paris, including the suburbs, tenements, and shanty towns where the working class and the poor live. In voiceover, the filmmaker laments the dwindling quality of life for the displaced, and questions where it leaves young and old alike. There is a scene of brawling juvenile delinquents where the violence exists in some weird zone between unbridled aggression and play--so much so, it almost looks staged. Watching L'amour existe now inspires conflicted reactions. While the effort is certainly sincere, at times the narration has a superior tone that makes the social message a little more puzzling, and the black-and-white photography has a tendency to romanticize the scenery. This latter problem is one that Pialat must have been aware of and is possibly using for effect. The final shots of the piece, where he shows how a simple change of camera position can change the Hand of Glory into a panhandler, remind us that cinema is about point of view. It's all about position of the seat you're watching from.

Additional bonus features continue to highlight the parallels between the fiction of L'enfance nue and the reality it draws from. Autour de "L'efnance nue" is a 1968 program from French television that chronicles Pialat's production and uses it as impetus for investigating the country's foster care system. There is also a 1973 interview with Pialat, a 2003 piece with Arlette Langmann and assistant director Patrick Grandperret, and a new video essay by Kent Jones.

This disc was provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

3 SILENT CLASSICS BY JOSEF VON STERNBERG - #528

"From now on you are my prisoner of war...and my prisoner of love."

It's interesting to look at Josef von Sternberg's early filmography and see how many films he worked on without credit or was eventually fired from. Having spent some time earlier this year researching one of those projects, I was aware he had gone through some struggles between his scrappy independent debut, The Salvation Hunters, in 1925 and his first studio picture, Underworld, in 1927, but you have to admire the guy for sticking it out. Then again, given how headstrong and defiantly individualistic his films were, I guess I shouldn't be surprised.

The new boxed set from Criterion, 3 Silent Classics by Josef von Sternberg, picks up with Underworld and shows us the director's early development. Though the Austrian immigrant would eventually be best known for his sexy collaborations with Marlene Dietrich, he started off in a much different place, exploring a more realistic world than the exaggerated, opulent, and oft-times grotesque settings that would distinguish The Scarlet Empress or his Gene Tierney-led noir The Shanghai Gesture . Yet, even when the young filmmaker was recreating the mean streets and the back alleys of urban America, von Sternberg still found ways to be von Sternberg. The trio in 3 Silent Classics are rich with memorable images and a confident command of the movie screen, rife with the kind of psychological expressionism that would set von Sternberg apart from the rest. (Be sure to watch Janet Bergrstrom's video essay on Underworld for a succinct and fascinating elaboration on von Sternberg's career prior to this breakthrough.)

. Yet, even when the young filmmaker was recreating the mean streets and the back alleys of urban America, von Sternberg still found ways to be von Sternberg. The trio in 3 Silent Classics are rich with memorable images and a confident command of the movie screen, rife with the kind of psychological expressionism that would set von Sternberg apart from the rest. (Be sure to watch Janet Bergrstrom's video essay on Underworld for a succinct and fascinating elaboration on von Sternberg's career prior to this breakthrough.)

* Underworld (1927): This early gangster picture was built off a story by Ben Hecht, with a little doctoring by Howard Hawks, the guys who would eventually make the genre-defining Scarface . Underworld precedes that film by five years, but it actually plays a little fresher than its more famous descendent. George Bancroft stars as the corpulent crime boss Bull Weed. Just think about that name for a second: he's a deadly, oversized animal whose presence in a healthy area strangles the life right out of it. Underworld opens with Bull robbing a bank by basically blowing it up, setting the stage for his getaway. He's a larger-than-life figure in a larger-than-life city--though ostensibly Chicago, it's also a place called Dreamland. It's a landscape with dark corners, and von Sternberg's use of its unnatural shadows would greatly influence film noir.

. Underworld precedes that film by five years, but it actually plays a little fresher than its more famous descendent. George Bancroft stars as the corpulent crime boss Bull Weed. Just think about that name for a second: he's a deadly, oversized animal whose presence in a healthy area strangles the life right out of it. Underworld opens with Bull robbing a bank by basically blowing it up, setting the stage for his getaway. He's a larger-than-life figure in a larger-than-life city--though ostensibly Chicago, it's also a place called Dreamland. It's a landscape with dark corners, and von Sternberg's use of its unnatural shadows would greatly influence film noir.

For as crazy as all the above sounds, and for how outrageous the film often looks, most of the Underworld plot is fairly conventional. Bull takes a down-on-his-luck, alcoholic lawyer nicknamed Rolls Royce (Clive Brook) under his wing, helping the brainiac get back on his feet. Bull's thanks? Royce falls for his moll, a flapper named Feathers (an alluring Evelyn Brent). Surprisingly, both feel guilty for succumbing to their sexual nature (a theme of von Sternberg's), but then, Bull is a pretty generous guy. He's the prototype of the neighborhood gangster who spreads his ill-gotten gains around. He'll sneak the money out of your pocket with one hand and give it back with the other.

Things come to a head during Underworld's most inventive scenario. The hometown criminals hold a party every year and declare a one-night armistice. They file into a ballroom, checking their coats and guns at the door, and dance the night away. The lead bad guys campaign for their girls and get the others to vote for their favorite to be Queen of the Ball, which sets up Bull's rival, the flower-shop-owner Buck Mulligan (Fred Kohler), to make his move. Bull fights back, gets pinched, and gets in hot water.

This central event is audacious and riveting, like what the consul of criminals from Fritz Lang's M gets up to when they want to have a good time. Ticker-tape is everywhere, booze is flowing, von Sternberg even takes the time to show pranks the hoods play on one another. One montage in particular has the director's fingerprints all over it. As the night wears on, von Sternberg takes us from the point where too much booze has been consumed to the point where the dancing has ended by putting together a series of grotesque close-ups of the guys and gals, showing just their faces as the hooch takes over. They get uglier and more nauseous with each new subject. The movie is pre-Code and so frank with its bad behavior, including some pretty salacious come-ons and visual entendres. It's the perfect subject matter for the director, whose films are always erotically charged and engorged on visual metaphor. Symbols often stand in for character--the actual feathers for Feathers, the flowers for Mulligan.

The acting is all solid in Underworld. von Sternberg keeps the exaggerated gestures under control, knowing what works best for his story. The most over-the-top moments are reserved for Bancroft's laughs, which are hearty and demented. There are some narrative leaps in a jailbreak in the final act, von Sternberg leaving out some of the steps, but given how much we've seen that kind of thing before, you can fill in the gaps, I'm sure. The movie has a sentimental yet effectively existential third act that avoids some of the clichés later gangster movies would run into the ground.

Surprisingly, Paramount thought Underworld was a stinker and limited its release. Ben Hecht apparently even tried to get his name taken off. Lucky for him, he failed. Word of mouth saved the picture, and Hecht won a writing Oscar for his story.

* The Last Command (1928): The great German star Emil Jannings (The Last Laugh, Faust [reviews]) stars as a former Russian general, Grand Duke Sergius Alexander, who has been exiled to Hollywood following the 1917 Russian Revolution. Sergius has taken to movie acting to make money, and as fate would have it, his first assignment is playing a Tsarist general. Little does he know, he was picked out of a pile of prospective performers by the movie's director (William Powell, The Thin Man ) because he is another expatriate, and back home, Sergius locked him in prison. The director wants to see what happened to the man who was so cruel to him.

) because he is another expatriate, and back home, Sergius locked him in prison. The director wants to see what happened to the man who was so cruel to him.

Cruelty is a running theme throughout The Last Command. The broken soldier is taunted by his fellow actors, who refuse to believe he is who he says he is. The general still carries around a medal the Czar gave him, it's a point of pride for him, and when we flash back to his downfall, we never see him without it. The majority of the movie takes place ten years prior, when Sergius was in charge of the front and the future film director was the head of an acting troupe that was going to perform for the soldiers. Noting that this radical influence has a pretty actress with him, Sergius decides to take advantage. He goads the director into rash action in order to arrest him, and then he takes Natalie (Evelyn Brent again) for his own.

The Last Command is based partially on the life of General Lodijensky, a real Russian leader who fled to Hollywood following the rise of the Communists. von Sternberg takes a sympathetic approach to his portrayal, but it's not one that is necessarily skewed to either side. Rather, the politics and the morality portrayed are complex and often contradictory. Jannings plays Sergius as a tragic figure. He treats citizens with a misguided entitlement, but he cares for his country and his soldiers. Natalie can't help but be attracted to him, she sees he's more than a uniform and fancy medals.

Eventually, the Revolution reaches a fever pitch, and here is where von Sternberg's sense of visual drama really shines. Cutting back and forth between the heads of the army living it up on a train and the gathering of Communists in the streets, von Sternberg eventually unleashes a sea of people in a series of breathtaking scenes where the revolutionaries focus their anger on the general. This sequence combines bombastic filmmaking with imagery straight out of Communist propaganda. Yet, the freedom fighters aren't shown as heroes. When the shoes are on the other feet, they can be just as awful to their fellow man as they believe the rulers were to them.

Jannings is a powerful screen actor, and he and von Sternberg work in concert to give The Last Command the kind of sturm und drang a tragedy of this kind requires. Jannings even picked up an Oscar for his efforts. Evelyn Brent is also really good as Natalie, who has some character changes that are far different and more challenging that the character arc of Feathers in Underworld. The period re-creations look phenomenal, and the climactic scenes of the flashback--which involve a train, a bridge, and a frozen lake--are not just amazing to look at, but they carry a devastating emotional punch.

Also quite neat to look at are von Sternberg's replications of a movie set. We get to see the backstage and the cattle call of extras, and we go out in front of the cameras to see Sergius' ironic fate drawn to a close. It's an effective finish, with the old soldier caught somewhere between the bloated buffoonery of Falstaff and the sad ravings of Lear. I am not sure I quite buy Powell's final lines (as seen on a title card, naturally), the sentiment seems forced--particularly as the closing image of the quiet soundstage works so well to blur the lines between fact and fiction. It's part metafiction, part a cinematic take on the theatrical curtain call.

* The Docks of New York (1928): Josef von Sternberg reteamed with his Underworld star George Bancroft for the second of many movies they made together. In this one, Bancroft plays Bill Roberts, a sailor on leave for one night in New York. Bill is a "stoker," one of the guys who works in the belly of the ship shoveling coal into its big burning engine. It's dirty work, and so when Bill goes on land, he's ready to blow off some steam of his own.

Plans go a different way, though, when he happens upon Mae (Betty Compson) flailing about in the water. She means to kill herself, but Bill isn't having it. He takes her to a nearby bar to dry out, and the two end up bonding. They've both seen their fair share of trouble, and there isn't a romantic bone in either of their bodies, but this is a von Sternberg film, so the animal attraction is enough. They spend the night dilly dallying around one another, and even end up dragging a preacher (Gustav von Seyffertitz) in to perform a marriage ceremony.

They also run afoul of trouble. The crew boss (Mitchell Lewis) from Bill's ship is drinking at the same bar, and he's got it in for Bill and wants a piece of Mae himself. His wife (Olga Baclanova) is none too thrilled with it either. There's going to be plenty of drinkin', brawlin', and carousin' before the night is through.

von Sternberg and cinematographer Harold Rosson create a rundown, realistic urban landscape for The Docks of New York. The bar that the couple spend most of their time in looks seedy, and Mae's apartment is falling apart. Scenes down in the bowels of the ship are remarkable documents of the industrial setting. The fire light and the glistening oil make Bill's world both hellacious and majestic. von Sternberg choreographs each scene down to the finest detail. Watch the mirrors in the bar. Just because Mae and Bill are alone in the foreground doesn't mean there isn't something going on in the background. von Sternberg sets it up so we can see the other patrons in the glass behind them, and they react and interact with what is in front of the camera.

Bancroft is excellent again. Bill doesn't have the magnanimity or expressiveness of Bull Weed, but the actor does manage an interior life for him. Much seems to be going on when he looks at Mae. Betty Compson is also very good. She is sexy and has attitude, but she's also weary. That said, the scene stealer is easily Olga Baclanova. She pulls off so much just by the way she stands, hand on hip, hip cocked out. She's getting fed up, and it shows.

Naturally, Bill wakes up the next morning with no real intention of sticking around with Mae, even though she kind of wishes he would. It's the first sentimentality that von Sternberg has allowed to creep into the picture. This is a love affair that is practical, not magical. That makes the little ground the two eventually do give to each other all the more meaningful. It took a lot for them to take those baby steps.

3 Silent Classics by Josef von Sternberg is one of my favorite boxed sets to come along this year. All the films are both engrossing to watch and to look at. von Sternberg had an individualistic personality, and his vision shows in every frame. From the gangster chic of Underworld to the period war drama The Last Command and through the stark melodrama of The Docks of New York, he was developing his craft and establishing a style that was all his own.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

It's interesting to look at Josef von Sternberg's early filmography and see how many films he worked on without credit or was eventually fired from. Having spent some time earlier this year researching one of those projects, I was aware he had gone through some struggles between his scrappy independent debut, The Salvation Hunters, in 1925 and his first studio picture, Underworld, in 1927, but you have to admire the guy for sticking it out. Then again, given how headstrong and defiantly individualistic his films were, I guess I shouldn't be surprised.

The new boxed set from Criterion, 3 Silent Classics by Josef von Sternberg, picks up with Underworld and shows us the director's early development. Though the Austrian immigrant would eventually be best known for his sexy collaborations with Marlene Dietrich, he started off in a much different place, exploring a more realistic world than the exaggerated, opulent, and oft-times grotesque settings that would distinguish The Scarlet Empress or his Gene Tierney-led noir The Shanghai Gesture

* Underworld (1927): This early gangster picture was built off a story by Ben Hecht, with a little doctoring by Howard Hawks, the guys who would eventually make the genre-defining Scarface

For as crazy as all the above sounds, and for how outrageous the film often looks, most of the Underworld plot is fairly conventional. Bull takes a down-on-his-luck, alcoholic lawyer nicknamed Rolls Royce (Clive Brook) under his wing, helping the brainiac get back on his feet. Bull's thanks? Royce falls for his moll, a flapper named Feathers (an alluring Evelyn Brent). Surprisingly, both feel guilty for succumbing to their sexual nature (a theme of von Sternberg's), but then, Bull is a pretty generous guy. He's the prototype of the neighborhood gangster who spreads his ill-gotten gains around. He'll sneak the money out of your pocket with one hand and give it back with the other.

Things come to a head during Underworld's most inventive scenario. The hometown criminals hold a party every year and declare a one-night armistice. They file into a ballroom, checking their coats and guns at the door, and dance the night away. The lead bad guys campaign for their girls and get the others to vote for their favorite to be Queen of the Ball, which sets up Bull's rival, the flower-shop-owner Buck Mulligan (Fred Kohler), to make his move. Bull fights back, gets pinched, and gets in hot water.

This central event is audacious and riveting, like what the consul of criminals from Fritz Lang's M gets up to when they want to have a good time. Ticker-tape is everywhere, booze is flowing, von Sternberg even takes the time to show pranks the hoods play on one another. One montage in particular has the director's fingerprints all over it. As the night wears on, von Sternberg takes us from the point where too much booze has been consumed to the point where the dancing has ended by putting together a series of grotesque close-ups of the guys and gals, showing just their faces as the hooch takes over. They get uglier and more nauseous with each new subject. The movie is pre-Code and so frank with its bad behavior, including some pretty salacious come-ons and visual entendres. It's the perfect subject matter for the director, whose films are always erotically charged and engorged on visual metaphor. Symbols often stand in for character--the actual feathers for Feathers, the flowers for Mulligan.

The acting is all solid in Underworld. von Sternberg keeps the exaggerated gestures under control, knowing what works best for his story. The most over-the-top moments are reserved for Bancroft's laughs, which are hearty and demented. There are some narrative leaps in a jailbreak in the final act, von Sternberg leaving out some of the steps, but given how much we've seen that kind of thing before, you can fill in the gaps, I'm sure. The movie has a sentimental yet effectively existential third act that avoids some of the clichés later gangster movies would run into the ground.

Surprisingly, Paramount thought Underworld was a stinker and limited its release. Ben Hecht apparently even tried to get his name taken off. Lucky for him, he failed. Word of mouth saved the picture, and Hecht won a writing Oscar for his story.

* The Last Command (1928): The great German star Emil Jannings (The Last Laugh, Faust [reviews]) stars as a former Russian general, Grand Duke Sergius Alexander, who has been exiled to Hollywood following the 1917 Russian Revolution. Sergius has taken to movie acting to make money, and as fate would have it, his first assignment is playing a Tsarist general. Little does he know, he was picked out of a pile of prospective performers by the movie's director (William Powell, The Thin Man

Cruelty is a running theme throughout The Last Command. The broken soldier is taunted by his fellow actors, who refuse to believe he is who he says he is. The general still carries around a medal the Czar gave him, it's a point of pride for him, and when we flash back to his downfall, we never see him without it. The majority of the movie takes place ten years prior, when Sergius was in charge of the front and the future film director was the head of an acting troupe that was going to perform for the soldiers. Noting that this radical influence has a pretty actress with him, Sergius decides to take advantage. He goads the director into rash action in order to arrest him, and then he takes Natalie (Evelyn Brent again) for his own.

The Last Command is based partially on the life of General Lodijensky, a real Russian leader who fled to Hollywood following the rise of the Communists. von Sternberg takes a sympathetic approach to his portrayal, but it's not one that is necessarily skewed to either side. Rather, the politics and the morality portrayed are complex and often contradictory. Jannings plays Sergius as a tragic figure. He treats citizens with a misguided entitlement, but he cares for his country and his soldiers. Natalie can't help but be attracted to him, she sees he's more than a uniform and fancy medals.

Eventually, the Revolution reaches a fever pitch, and here is where von Sternberg's sense of visual drama really shines. Cutting back and forth between the heads of the army living it up on a train and the gathering of Communists in the streets, von Sternberg eventually unleashes a sea of people in a series of breathtaking scenes where the revolutionaries focus their anger on the general. This sequence combines bombastic filmmaking with imagery straight out of Communist propaganda. Yet, the freedom fighters aren't shown as heroes. When the shoes are on the other feet, they can be just as awful to their fellow man as they believe the rulers were to them.

Jannings is a powerful screen actor, and he and von Sternberg work in concert to give The Last Command the kind of sturm und drang a tragedy of this kind requires. Jannings even picked up an Oscar for his efforts. Evelyn Brent is also really good as Natalie, who has some character changes that are far different and more challenging that the character arc of Feathers in Underworld. The period re-creations look phenomenal, and the climactic scenes of the flashback--which involve a train, a bridge, and a frozen lake--are not just amazing to look at, but they carry a devastating emotional punch.

Also quite neat to look at are von Sternberg's replications of a movie set. We get to see the backstage and the cattle call of extras, and we go out in front of the cameras to see Sergius' ironic fate drawn to a close. It's an effective finish, with the old soldier caught somewhere between the bloated buffoonery of Falstaff and the sad ravings of Lear. I am not sure I quite buy Powell's final lines (as seen on a title card, naturally), the sentiment seems forced--particularly as the closing image of the quiet soundstage works so well to blur the lines between fact and fiction. It's part metafiction, part a cinematic take on the theatrical curtain call.

* The Docks of New York (1928): Josef von Sternberg reteamed with his Underworld star George Bancroft for the second of many movies they made together. In this one, Bancroft plays Bill Roberts, a sailor on leave for one night in New York. Bill is a "stoker," one of the guys who works in the belly of the ship shoveling coal into its big burning engine. It's dirty work, and so when Bill goes on land, he's ready to blow off some steam of his own.

Plans go a different way, though, when he happens upon Mae (Betty Compson) flailing about in the water. She means to kill herself, but Bill isn't having it. He takes her to a nearby bar to dry out, and the two end up bonding. They've both seen their fair share of trouble, and there isn't a romantic bone in either of their bodies, but this is a von Sternberg film, so the animal attraction is enough. They spend the night dilly dallying around one another, and even end up dragging a preacher (Gustav von Seyffertitz) in to perform a marriage ceremony.

They also run afoul of trouble. The crew boss (Mitchell Lewis) from Bill's ship is drinking at the same bar, and he's got it in for Bill and wants a piece of Mae himself. His wife (Olga Baclanova) is none too thrilled with it either. There's going to be plenty of drinkin', brawlin', and carousin' before the night is through.

von Sternberg and cinematographer Harold Rosson create a rundown, realistic urban landscape for The Docks of New York. The bar that the couple spend most of their time in looks seedy, and Mae's apartment is falling apart. Scenes down in the bowels of the ship are remarkable documents of the industrial setting. The fire light and the glistening oil make Bill's world both hellacious and majestic. von Sternberg choreographs each scene down to the finest detail. Watch the mirrors in the bar. Just because Mae and Bill are alone in the foreground doesn't mean there isn't something going on in the background. von Sternberg sets it up so we can see the other patrons in the glass behind them, and they react and interact with what is in front of the camera.

Bancroft is excellent again. Bill doesn't have the magnanimity or expressiveness of Bull Weed, but the actor does manage an interior life for him. Much seems to be going on when he looks at Mae. Betty Compson is also very good. She is sexy and has attitude, but she's also weary. That said, the scene stealer is easily Olga Baclanova. She pulls off so much just by the way she stands, hand on hip, hip cocked out. She's getting fed up, and it shows.

Naturally, Bill wakes up the next morning with no real intention of sticking around with Mae, even though she kind of wishes he would. It's the first sentimentality that von Sternberg has allowed to creep into the picture. This is a love affair that is practical, not magical. That makes the little ground the two eventually do give to each other all the more meaningful. It took a lot for them to take those baby steps.

3 Silent Classics by Josef von Sternberg is one of my favorite boxed sets to come along this year. All the films are both engrossing to watch and to look at. von Sternberg had an individualistic personality, and his vision shows in every frame. From the gangster chic of Underworld to the period war drama The Last Command and through the stark melodrama of The Docks of New York, he was developing his craft and establishing a style that was all his own.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Labels:

fritz lang,

hawks,

josef von sternberg,

silent cinema

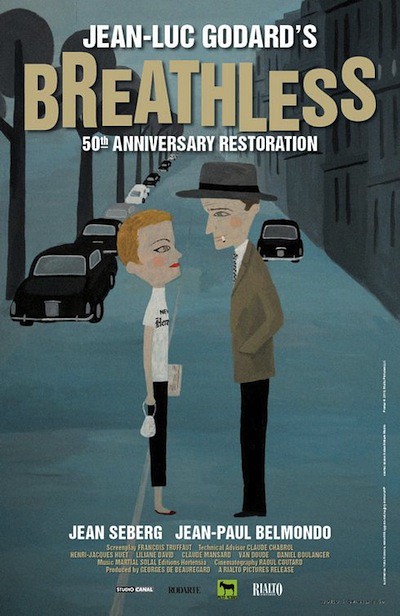

BREATHLESS 50th Anniversary Restoration

"To become immortal...and then die."

In his recent review of the 50th anniversary touring print of Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless, Michael Phillips quotes Jean-Paul Belmondo's dialogue from the film, when he tells Jean Seberg "I wanted to see if I'd be glad to see you again." Hearing that made Phillips realize how glad he was to be screening the movie after many years. "Turns out I was dying to see Breathless again," he writes, "and didn't even know it."

I feel the same way every time I see Breathless. It's been less than three years between viewings for me, having last watched Godard's 1960 masterpiece back when Criterion reissued the film in 2007 [review]. It's the kind of movie you think you know backwards and forwards until you start it up and realize how much of it you have forgotten and just how much cinema is there to sink your teeth into.

Despite owning the aforementioned DVD, I ventured out to the theatre to catch a screening of the new restoration, which opens at Cinema 21 here in Portland on August 13 [other tour dates here]. It was my first time seeing it on a movie screen, and given what a tremendous experience I had in recent months with the restorations of both Ran [review] and The Red Shoes [review], I thought it would be incredibly foolish to pass up on the opportunity. The new print, supervised by cinematographer Raoul Coutard, is everything one could hope it would be. I am not sure it is necessarily better than the DVD version, the previous restoration was phenomenal, but here is an opportunity to see the same clarity writ large. The Breathless I saw looked exceptional, and there wasn't a scratch on it.

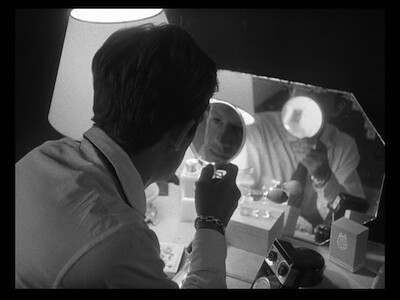

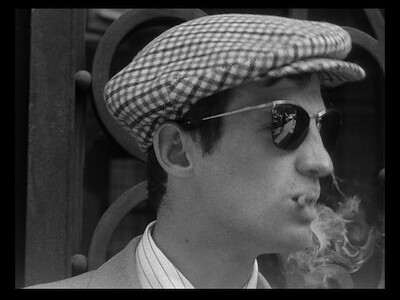

What continues to surprise me about Godard's audacious debut is that, every time I partake of it, I find new things to focus on. His tale of a two-bit gangster (Belmondo) and the American girl (Seberg) he hides out with is so full of story and character, I don't anticipate ever running out of angles to approach it from. Breathless is an extended conversation between Godard and his audience. He sets up Belmondo as his proxy, and the actor uses the early part of the film to talk directly to us. We are his partners in crime, his confidantes, and in a way, he seduces us, we are another of his many pick-ups. He steals a car and takes us for a ride; likewise, Jean-Luc Godard hijacked cinema and never gave it back.

For as charismatic as Belmondo is, this time around I found myself focusing on Jean Seberg. I can't imagine that I never picked up on the fact that her character, Patricia, was pregnant when I saw the movie before--she even outright says so--but then, I didn't mention it in my last review, which is kind of weird. This time around I clued in right away, as soon as her friend the reporter (whom Belmondo is right about, he doesn't seem on the up and up) gives her the novel and says it's about a girl like her and hopes that her situation won't go the same way. A little light bulb went off, and by keeping that light on, I was able to appreciate Seberg's performance in a whole new way. Patricia isn't merely the romantic ideal whose very arrival on screen is trumpeted by a surge of music, but someone far more complex than I realized.

Watch Seberg in the scenes immediately after her meeting with the reporter. Everything she does shows how much the pregnancy is on her mind, be it the obvious action of examining her figure in a window reflection or more subtle, like the way she sits on the bed with Belmondo and clutches a teddy bear to her chest. One can guess that dreams of domestic bliss are forming in her head, and she is being so feisty with him because she wants to know that he really cares. Unsurprisingly, he reacts badly when she tells him what is happening, and the subject never comes up again. More telling, Patricia's whole demeanor changes afterward, she forgets herself and subsumes her needs to fit his. She becomes part of his childish plot. What she does at the end of the picture isn't nearly as capricious as it might seem: she is getting herself back and making a decision to get away from a man who will never grow up. That last look she gives, then, just might be her realizing she can never get away, she will carry him with her in a very real way.

Belmondo certainly doesn't seem like a guy who has a firm commitment to commitment. Most of the first act shows him running away, be it from other girls or from the scene of the crime. Only Patricia makes him stop, and that's mainly because he thinks he can't have her and can't stand that others want her. The movie is Breathless because he is rushing from start to finish. What is he rushing to, though? His adolescent dreams of being the big man, of being an epic gangster or a full-on movie star, like Humphrey Bogart? Given how he ends up, though, maybe James Cagney would have been better. "Made it, Ma! Top of the world!" It would appear that infamy and immortality are interchangeable.

would have been better. "Made it, Ma! Top of the world!" It would appear that infamy and immortality are interchangeable.

It wasn't Belmondo's character, though, who gave us the quote "To become immortal...and then die." That was Jean-Pierre Melville playing the pretentious novelist. (Excepting this nugget, the rest of his dialogue is the funniest material in the movie.) It's an immature vision of success. Rimbaud, James Dean--better to burn out than fade away. Yet, it's not really Belmondo's playtime hood that is achieving the immortality, it's Godard. Breathless was the young filmmaker's arrival, and he essentially manhandled cinema the way Belmondo mugged that guy in the bathroom, taking what he needed and otherwise leaving the victim for dead.

Even now, most films don't have the vim that Breathless has. It keeps moving, pushing through the streets of Paris, ferreting out its story. For as loose as the film can be, if you map out how the story works, how characters come in and out of the narrative, the way dialogue and action calls back to earlier scenes, you'll find that Godard has an impressive amount of control over what is being shown. It may be a coincidence that Belmondo drives by the girlfriend he robbed earlier just as she reads about his killing a cop in the newspaper, but really, there is no coincidence in story. That kind of thing is planned.

At the same time, there is an immediacy to the movie that can't be contrived or replicated. Notice how there are always people in the street watching the action, even glancing at the camera. Watching Breathless always feels like it is happening right at the moment, the movie never really occurred until just now when Belmondo looked into Coutard's lens and spoke to us. It's a storytelling quality that Godard owns like no one else, and you only have to watch the 1980s remake of Breathless to see how unattainable it is. (I recently sat down with that travesty, directed by Jim McBride and starring Richard Gere. I posted my reactions live on Twitter, and you can read them here, here, and here, if you like.)

of Breathless to see how unattainable it is. (I recently sat down with that travesty, directed by Jim McBride and starring Richard Gere. I posted my reactions live on Twitter, and you can read them here, here, and here, if you like.)

It's also why Breathless feels new no matter when or how many times you watch it. You might forget that you are dying to see it again, as Michael Phillips did, but it won't take more than a few frames of film to remember.

For those who aren't getting the 50th anniversary print in their town, the movie is also being released by Criterion on Blu-ray on September 14. I doubt this will be a different transfer from the 2007 DVD, it will likely just be spruced up for the new format. (The Criterion site says that it will have an "uncompressed monaural soundtrack" that is exclusive to this edition.) Still, if you've upgraded to the new tech, this is likely a movie you'll want to upgrade as well. Any excuse to give it another spin.

on September 14. I doubt this will be a different transfer from the 2007 DVD, it will likely just be spruced up for the new format. (The Criterion site says that it will have an "uncompressed monaural soundtrack" that is exclusive to this edition.) Still, if you've upgraded to the new tech, this is likely a movie you'll want to upgrade as well. Any excuse to give it another spin.

Also, take a look at the new trailer for this revival. It's a straight-up remake of the original 1960 trailer, but in English and with splashes of color. Kind of cool, kind of strange, but also kind of fun:

This film was reviewed thanks to a promotional screening hosted by Cinema 21.

In his recent review of the 50th anniversary touring print of Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless, Michael Phillips quotes Jean-Paul Belmondo's dialogue from the film, when he tells Jean Seberg "I wanted to see if I'd be glad to see you again." Hearing that made Phillips realize how glad he was to be screening the movie after many years. "Turns out I was dying to see Breathless again," he writes, "and didn't even know it."

I feel the same way every time I see Breathless. It's been less than three years between viewings for me, having last watched Godard's 1960 masterpiece back when Criterion reissued the film in 2007 [review]. It's the kind of movie you think you know backwards and forwards until you start it up and realize how much of it you have forgotten and just how much cinema is there to sink your teeth into.

Despite owning the aforementioned DVD, I ventured out to the theatre to catch a screening of the new restoration, which opens at Cinema 21 here in Portland on August 13 [other tour dates here]. It was my first time seeing it on a movie screen, and given what a tremendous experience I had in recent months with the restorations of both Ran [review] and The Red Shoes [review], I thought it would be incredibly foolish to pass up on the opportunity. The new print, supervised by cinematographer Raoul Coutard, is everything one could hope it would be. I am not sure it is necessarily better than the DVD version, the previous restoration was phenomenal, but here is an opportunity to see the same clarity writ large. The Breathless I saw looked exceptional, and there wasn't a scratch on it.

What continues to surprise me about Godard's audacious debut is that, every time I partake of it, I find new things to focus on. His tale of a two-bit gangster (Belmondo) and the American girl (Seberg) he hides out with is so full of story and character, I don't anticipate ever running out of angles to approach it from. Breathless is an extended conversation between Godard and his audience. He sets up Belmondo as his proxy, and the actor uses the early part of the film to talk directly to us. We are his partners in crime, his confidantes, and in a way, he seduces us, we are another of his many pick-ups. He steals a car and takes us for a ride; likewise, Jean-Luc Godard hijacked cinema and never gave it back.

For as charismatic as Belmondo is, this time around I found myself focusing on Jean Seberg. I can't imagine that I never picked up on the fact that her character, Patricia, was pregnant when I saw the movie before--she even outright says so--but then, I didn't mention it in my last review, which is kind of weird. This time around I clued in right away, as soon as her friend the reporter (whom Belmondo is right about, he doesn't seem on the up and up) gives her the novel and says it's about a girl like her and hopes that her situation won't go the same way. A little light bulb went off, and by keeping that light on, I was able to appreciate Seberg's performance in a whole new way. Patricia isn't merely the romantic ideal whose very arrival on screen is trumpeted by a surge of music, but someone far more complex than I realized.

Watch Seberg in the scenes immediately after her meeting with the reporter. Everything she does shows how much the pregnancy is on her mind, be it the obvious action of examining her figure in a window reflection or more subtle, like the way she sits on the bed with Belmondo and clutches a teddy bear to her chest. One can guess that dreams of domestic bliss are forming in her head, and she is being so feisty with him because she wants to know that he really cares. Unsurprisingly, he reacts badly when she tells him what is happening, and the subject never comes up again. More telling, Patricia's whole demeanor changes afterward, she forgets herself and subsumes her needs to fit his. She becomes part of his childish plot. What she does at the end of the picture isn't nearly as capricious as it might seem: she is getting herself back and making a decision to get away from a man who will never grow up. That last look she gives, then, just might be her realizing she can never get away, she will carry him with her in a very real way.

Belmondo certainly doesn't seem like a guy who has a firm commitment to commitment. Most of the first act shows him running away, be it from other girls or from the scene of the crime. Only Patricia makes him stop, and that's mainly because he thinks he can't have her and can't stand that others want her. The movie is Breathless because he is rushing from start to finish. What is he rushing to, though? His adolescent dreams of being the big man, of being an epic gangster or a full-on movie star, like Humphrey Bogart? Given how he ends up, though, maybe James Cagney

It wasn't Belmondo's character, though, who gave us the quote "To become immortal...and then die." That was Jean-Pierre Melville playing the pretentious novelist. (Excepting this nugget, the rest of his dialogue is the funniest material in the movie.) It's an immature vision of success. Rimbaud, James Dean--better to burn out than fade away. Yet, it's not really Belmondo's playtime hood that is achieving the immortality, it's Godard. Breathless was the young filmmaker's arrival, and he essentially manhandled cinema the way Belmondo mugged that guy in the bathroom, taking what he needed and otherwise leaving the victim for dead.

Even now, most films don't have the vim that Breathless has. It keeps moving, pushing through the streets of Paris, ferreting out its story. For as loose as the film can be, if you map out how the story works, how characters come in and out of the narrative, the way dialogue and action calls back to earlier scenes, you'll find that Godard has an impressive amount of control over what is being shown. It may be a coincidence that Belmondo drives by the girlfriend he robbed earlier just as she reads about his killing a cop in the newspaper, but really, there is no coincidence in story. That kind of thing is planned.

At the same time, there is an immediacy to the movie that can't be contrived or replicated. Notice how there are always people in the street watching the action, even glancing at the camera. Watching Breathless always feels like it is happening right at the moment, the movie never really occurred until just now when Belmondo looked into Coutard's lens and spoke to us. It's a storytelling quality that Godard owns like no one else, and you only have to watch the 1980s remake

It's also why Breathless feels new no matter when or how many times you watch it. You might forget that you are dying to see it again, as Michael Phillips did, but it won't take more than a few frames of film to remember.

For those who aren't getting the 50th anniversary print in their town, the movie is also being released by Criterion on Blu-ray

Also, take a look at the new trailer for this revival. It's a straight-up remake of the original 1960 trailer, but in English and with splashes of color. Kind of cool, kind of strange, but also kind of fun:

This film was reviewed thanks to a promotional screening hosted by Cinema 21.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)