One piece of business: I broke my own philosophy and joined a club that would have me as a member...

Online Film Critics Society: Jamie S. Rich: "MEDIA AFFILIATION DVD Talk Criterion Confessions Confessions of a Pop Fan LOCATION Portland, OR ABOUT JAMIE Jamie S. Rich is a novelist ..."

So, yay that!

Now, on to the reviews:

IN THEATRES...

* Henri-Georges Clouzot's Inferno, the amazing tale of a film director and the movie that burned away. For two nights only at the NW Film Center!

* Howl, the story of the Allen Ginsberg poem, with James Franco as Ginsberg. Plus, cartoons.

* I'm Still Here, Joaquin Phoenix takes one to the face.

* Lebanon, a tense Israeli war movie that takes place entirely inside a tank. Trust me, you want to catch this one. It's riveting.

* Let Me In, an exercise in redundancy. I'm debating between "No thanks, I'd rather stay outside," and "Fine, but once you're in, stay in!"

* Machete, Robert Rodriguez's new movie is probably exactly what you think it is.

* The Social Network--Sorkin? Fincher? Me and this movie are totally friends.

* The Town, Ben Affleck has made the best Michael Mann movie this century. (Bring it, nerds!) Check out my friend Plastorm's review, too.

* Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps, though not as incisive as the original, it's pretty good...until Oliver Stone loses his erection. He needs movie viagra.

* A Woman, a Gun and a Noodle Shop, Zhang Yimou's flaccid remake of Blood Simple. And by "flaccid," I mean "limp." Like a noodle. Haw! Get it?

ON DVD/BD...

* Ajami, called the Israeli Pulp Fiction by some, its narrative acrobatics left me a little cold.

* Bored to Death: The Complete First Season, Jason Schwartzman is great in the Jonathan Ames-created TV show. Modern literary rom com mashed-up with the private detective genre.

* The Exploding Girl, a quiet peek into the life of one girl. Starring Zoe Kazan in a career-making performance.

* The Law, this late '50s genre-buster from Jules Dassin is wicked fun. Gina Lollobrigida can pull a knife on me any time.

* Leonard Cohen - Bird On a Wire, the "lost" chronicle of the bard's 1972 concert tour has been found, and it's essential viewing.

* None but the Lonely Heart, an edgy Cary Grant performance makes this Clifford Odets production.

* One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest - Collector's Edition, a very cool new packaging of an exceptional movie.

* The Secret in Their Eyes, the literary thriller took this year's Foreign Language Oscar for Argentina, and it's still good on DVD.

* Secretary, a sweet romance in weird kid's clothing. Maggie Gyllenhaal and James Spader are amazing, but this Blu-Ray reissue could have been better.

* Shirin, a fascinating experiment from Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami turns the moviegoing experience around on the audience.

* Soundtrack for a Revolution, a good but unfocused documentary about the music of the Civil Rights movement, with contemporary artists doing new versions of the old songs.

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Monday, September 27, 2010

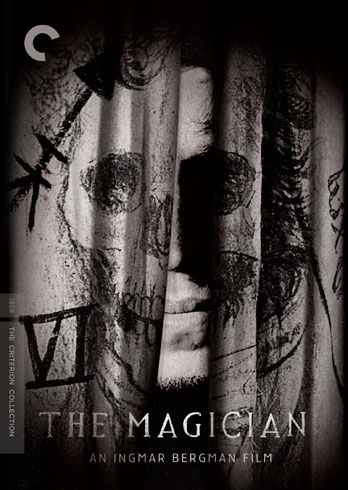

THE MAGICIAN (Blu-Ray) - #537

"Pretense, false promises, double bottoms."

Ingmar Bergman's 1958 supernatural caper The Magician is one of those movies where nothing is as it seems, everything has two explanations, and the very notion of the "knowable" is called into question. Its knotted narrative is full of tricks and surprises, some obvious and others not so much, and by the end, Bergman has pulled off his own cinematic magic trick, leaving the audience wondering just which of his flickering illusions to believe.

The Magician opens in a Swedish forest somewhere near the tail end of the industrial age. We move in on a traveling sideshow led by one Dr. Vogler (Max von Sydow). Amongst his group are the master of ceremonies Tubal (Ake Fridell), Vogler's grandmother (Naima Wifstrand), the androgynous Mr. Aman (Ingrid Thulin), and the carriage driver, Simson (Lars Ekborg). We are given multiple explanations as to what this band of performers does. They regularly insist on their own lack of veracity--they do tricks for show, nothing more. They sell noxious potions that are really interchangeable and have no actual effect. Or do they? Granny is a witch, so maybe she does know some magic spells. Dr. Vogler is also said to be a master hypnotist who heals people with magnets. Tall, dark, and bearded, Vogler is an imposing figure; he is also mute.

In the woods, the troupe finds an ailing actor (Bengt Ekerot). They take him in their carriage, and he dies before the group reaches civilization. They take the body to the police, but find they are in trouble for other infractions. Their various reputations precede them. The performers are hauled before a tribunal of three: a smug police chief named Starbeck (Tovio Pawlo), a local scientist called Dr. Vergerus (Gunnar Björnstrand), and Consul Egerman (Erland Josephson), a town dignitary. They demand Vogler and his people account for themselves, and even push for a demonstration of the Doc's powers. It turns out that Vergerus and Egerman have a bet going. Vergerus believes that all this world has to offer is what science can verify, whereas Egerman insists there are unquantifiable forces always at work.

Most of The Magician takes place over the tense night in custody at Egerman's home. The various members of Vogler's crew interact with Egerman's staff, seducing them and demonstrating their special talents. There is a subtle comment on class here: the more common folk believe in religion and magic, the more affluent and educated do not. Yet, as Bergman holds back the curtain and shows us things that defy rational explanation, who are we to side with? The dead actor wanders the house as a ghost, interacting with Granny and Vogler. A thunder storm brings strange portents. Passions are stirred. Mrs. Egerman (Gertrud Fridh) is drawn to Vogler. She claims to want the psychic to explain the recent death of her daughter, but her heaving bosom suggests she desires more. Likewise, Vergerus makes no bones about his interest in Aman, though Aman proves more loyal than he expected--all the more frustrating, as what Vergerus perceives as Vogler's charlatanism represents everything the scientist hates.

Bergman is blessed with a powerhouse cast for The Magician. von Sydow, Thulin, Josephson, and many of the others are all recurring members of his reparatory, as is Bibi Andersson, who plays Sara, a servant girl who takes a love potion with Simson. As the night wears on and all the players become entangled, it's hard not to think of Bergman's comedy Smiles of a Summer Night; The Magician is like the brooding companion piece, Frowns on an Autumn Evening. With dawn approaching, more layers are folded back, more masks dropped. Everyone has hidden agendas, everyone has secrets. Vogler acts as a funhouse mirror for all of them: they see in him what they want to see.

This all leads to a command performance for the tribunal, their servants, and their wives. Vogler and his people turn the tables, and rather than expose themselves, they expose things about their accusers. One man who is part of Egerman's guard is so undone, he even resorts to violence. There is something about Vogler's chosen practice that makes the common men angry. His dark arts are an affront to what they believe, a challenge to their morals and their mortality. In the bonus features, critic Peter Cowie suggests this was Bergman's metaphor for the director's contentious relationship with a moviegoing audience hostile to the complicated metaphysics that are a hallmark of his work.

Regardless, the magician's actions put into motion the final act of the film, where the thinking man, Dr. Vergerus, must confront Vogler's illusions directly. It's hard to say much more without giving it away. My instinct to contextualize the story by the genre it most reminds me of would even reveal too much. Suffice to say, the final act of The Magician has some bold story moves, as well as some of Bergman's most audacious surreal imagery. He and cameraman Gunnar Fischer and production designer P.A. Lundgren could have taken what they started here and made one hell of a carnival haunted house, let me tell you.

There is a lot to digest in The Magician. All the characters are dealt with before the finale, all the subplots wrapped up, and together they create a dramatic tapestry that is fun to pick apart and analyze. Emphasis on fun. Bergman's movie is one of his more self-conscious entertainments. It's spooky and challenging, and Bergman uses all the mechanics of a good fireside ghost story. If Cowie is right about the director responding to his harshest critics, then it makes the strange Hollywood-like ending that caps the picture make more sense. It's similar to the swindle of Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman's Adaptation , like Ingmar is saying, "You can have the cheap entertainment you so desire, I can fit my cinema of ideas into that, no problem." Yet, the ultimate sleight of hand is The Magician isn't really that thing audiences think they want, yet it sneaks in anyhow, and quality wins out after all.

, like Ingmar is saying, "You can have the cheap entertainment you so desire, I can fit my cinema of ideas into that, no problem." Yet, the ultimate sleight of hand is The Magician isn't really that thing audiences think they want, yet it sneaks in anyhow, and quality wins out after all.

The 1080p, full frame image on The Magician - Criterion Collection is gobsmacking in its clarity. The black-and-white photography looks gorgeous on this disc. There isn't a scratch on the film, and the values between light and dark are wonderful. Every little detail comes through absolutely. Though made in 1958, The Magician looks brand new.

The uncompressed mono audio track is also exceptionally clear. There is no hiss or any off sounds. There is even some subtlety, despite only being a single channel. Take note, for instance, of a scene between Vogler and his wife where a bell peals in the distance. For a second, I didn't even realize it was in the movie, I thought it was somewhere outside my house.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Ingmar Bergman's 1958 supernatural caper The Magician is one of those movies where nothing is as it seems, everything has two explanations, and the very notion of the "knowable" is called into question. Its knotted narrative is full of tricks and surprises, some obvious and others not so much, and by the end, Bergman has pulled off his own cinematic magic trick, leaving the audience wondering just which of his flickering illusions to believe.

The Magician opens in a Swedish forest somewhere near the tail end of the industrial age. We move in on a traveling sideshow led by one Dr. Vogler (Max von Sydow). Amongst his group are the master of ceremonies Tubal (Ake Fridell), Vogler's grandmother (Naima Wifstrand), the androgynous Mr. Aman (Ingrid Thulin), and the carriage driver, Simson (Lars Ekborg). We are given multiple explanations as to what this band of performers does. They regularly insist on their own lack of veracity--they do tricks for show, nothing more. They sell noxious potions that are really interchangeable and have no actual effect. Or do they? Granny is a witch, so maybe she does know some magic spells. Dr. Vogler is also said to be a master hypnotist who heals people with magnets. Tall, dark, and bearded, Vogler is an imposing figure; he is also mute.

In the woods, the troupe finds an ailing actor (Bengt Ekerot). They take him in their carriage, and he dies before the group reaches civilization. They take the body to the police, but find they are in trouble for other infractions. Their various reputations precede them. The performers are hauled before a tribunal of three: a smug police chief named Starbeck (Tovio Pawlo), a local scientist called Dr. Vergerus (Gunnar Björnstrand), and Consul Egerman (Erland Josephson), a town dignitary. They demand Vogler and his people account for themselves, and even push for a demonstration of the Doc's powers. It turns out that Vergerus and Egerman have a bet going. Vergerus believes that all this world has to offer is what science can verify, whereas Egerman insists there are unquantifiable forces always at work.

Most of The Magician takes place over the tense night in custody at Egerman's home. The various members of Vogler's crew interact with Egerman's staff, seducing them and demonstrating their special talents. There is a subtle comment on class here: the more common folk believe in religion and magic, the more affluent and educated do not. Yet, as Bergman holds back the curtain and shows us things that defy rational explanation, who are we to side with? The dead actor wanders the house as a ghost, interacting with Granny and Vogler. A thunder storm brings strange portents. Passions are stirred. Mrs. Egerman (Gertrud Fridh) is drawn to Vogler. She claims to want the psychic to explain the recent death of her daughter, but her heaving bosom suggests she desires more. Likewise, Vergerus makes no bones about his interest in Aman, though Aman proves more loyal than he expected--all the more frustrating, as what Vergerus perceives as Vogler's charlatanism represents everything the scientist hates.

Bergman is blessed with a powerhouse cast for The Magician. von Sydow, Thulin, Josephson, and many of the others are all recurring members of his reparatory, as is Bibi Andersson, who plays Sara, a servant girl who takes a love potion with Simson. As the night wears on and all the players become entangled, it's hard not to think of Bergman's comedy Smiles of a Summer Night; The Magician is like the brooding companion piece, Frowns on an Autumn Evening. With dawn approaching, more layers are folded back, more masks dropped. Everyone has hidden agendas, everyone has secrets. Vogler acts as a funhouse mirror for all of them: they see in him what they want to see.

This all leads to a command performance for the tribunal, their servants, and their wives. Vogler and his people turn the tables, and rather than expose themselves, they expose things about their accusers. One man who is part of Egerman's guard is so undone, he even resorts to violence. There is something about Vogler's chosen practice that makes the common men angry. His dark arts are an affront to what they believe, a challenge to their morals and their mortality. In the bonus features, critic Peter Cowie suggests this was Bergman's metaphor for the director's contentious relationship with a moviegoing audience hostile to the complicated metaphysics that are a hallmark of his work.

Regardless, the magician's actions put into motion the final act of the film, where the thinking man, Dr. Vergerus, must confront Vogler's illusions directly. It's hard to say much more without giving it away. My instinct to contextualize the story by the genre it most reminds me of would even reveal too much. Suffice to say, the final act of The Magician has some bold story moves, as well as some of Bergman's most audacious surreal imagery. He and cameraman Gunnar Fischer and production designer P.A. Lundgren could have taken what they started here and made one hell of a carnival haunted house, let me tell you.

There is a lot to digest in The Magician. All the characters are dealt with before the finale, all the subplots wrapped up, and together they create a dramatic tapestry that is fun to pick apart and analyze. Emphasis on fun. Bergman's movie is one of his more self-conscious entertainments. It's spooky and challenging, and Bergman uses all the mechanics of a good fireside ghost story. If Cowie is right about the director responding to his harshest critics, then it makes the strange Hollywood-like ending that caps the picture make more sense. It's similar to the swindle of Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman's Adaptation

The 1080p, full frame image on The Magician - Criterion Collection is gobsmacking in its clarity. The black-and-white photography looks gorgeous on this disc. There isn't a scratch on the film, and the values between light and dark are wonderful. Every little detail comes through absolutely. Though made in 1958, The Magician looks brand new.

The uncompressed mono audio track is also exceptionally clear. There is no hiss or any off sounds. There is even some subtlety, despite only being a single channel. Take note, for instance, of a scene between Vogler and his wife where a bell peals in the distance. For a second, I didn't even realize it was in the movie, I thought it was somewhere outside my house.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Labels:

bergman,

blu-ray,

charlie kaufman,

spike jonze

Saturday, September 25, 2010

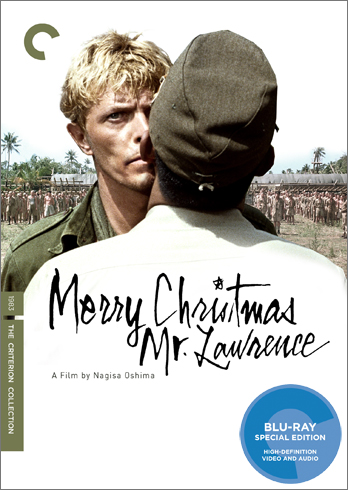

MERRY CHRISTMAS MR. LAWRENCE (Blu-Ray) - #535

1942. A Japanese prison camped for Allied POWs captured in Korea and other parts of Southeast Asia. This is the setting for Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, Nagisa Oshima's 1983 film of hidden desires behind the barbed-wired fences.

Tom Conti leads the film as Colonel John Lawrence, a British officer with some expertise and experience in Asia. His ability to speak Japanese makes him a valuable liaison between the prison guards and their prisoners, even if it does make some of the other men suspicious. At the start of the movie, Lawrence is roused from sleep by the gruff-voiced Sgt. Gengo Hara (Takeshi Kitano in an early role; he is billed as simply "Takeshi"). One of Hara's men (Johnny Okura) has been caught in a compromising position with a Dutch prisoner (Alistair Browning), and Hara wants Lawrence to both translate for the victim and be witness to what happens. Hara would like to punish his soldier without involving his commander, the aloof Captain Yonoi (musician Ryûichi Sakamoto). Homosexuality is not to be tolerated, particularly if the captor forced himself on the captive.

Yonoi does end up stumbling into the situation, but he has little time for it. He is on his way to base where a tribunal has been called to deal with another captured Brit. Major Jack "Strafer" Celliers (bleached-hair, Let's Dance-era David Bowie) was engaging in what was apparently some pretty effective guerilla warfare before he ran afoul of the Japanese army, and his lack of cooperation now that he is in their hands has confounded the top brass. Yonoi is brought in for some outside perspective--only his superiors don't know how far outside it is. In one of the least subtle "falling in love" scenes you can imagine, Oshima shows Yonoi as hypnotized by the blonde-haired grunt. The music swells, the camera pushes in, Yonoi is transfixed. Benefit of the doubt, maybe Oshima was purposely playing on old-fashioned romance conventions. Regardless, we get the point.

Unsurprisingly, Yonoi takes Celliers back to his prison camp, where his fixation doesn't go unnoticed. Not by Lawrence, Hara, or even Celliers himself. Yonoi tries to show off for his crush; he practices his sword fighting where the convalescing prisoner can hear his grunts and moans. For his part, Celliers becomes a subversive element in the camp, particularly when he challenges Yonoi's orders for a period of fasting by going out and picking edible flowers for his bunkmates. Again, the romantic imagery is pretty clear, though this colorful display is far more effective. If I had a still of the scene, I would caption it like a title from a Bullwinkle cartoon: "Make Love, Not War; or, Gather Ye Rosebuds While Ye May."

Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence is a strange picture. It is based on the memoirs of a real prisoner of war, Laurens Van der Post, though the script by Oshima and Paul Mayersberg (The Man Who Fell to Earth, The Last Samurai

) more strongly resembles a Yukio Mishima novel. Like Mishima, the story is concerned with honor and how men conduct themselves in structured situations. Suppressed passions rise up in strange ways, and on a symbolic level, homosexuality is equated with a physical deformity. Not as a value judgment, mind you, both Oshima and Mishima had a broad sexual view, but as something to be hidden lest you be judged. In Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, we see Celliers' early life and his young brother (James Malcolm), who had a hump on his back. Celliers tells Lawrence how he was too morally weak to stand up for his sibling when the pack victimized him, something he considers to be his greatest failing; the events at the POW camp will at long last provide him an opportunity for redemption.

There's a lot of strong stuff in Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence. The complexity of the drama and the psychology of the characters is fascinating. Lawrence forms an unexpected bond with both Hara and Celliers, driven together by the odd behavior of Yonoi. The Captain's own secret shame ends up connecting to how he finally deals with the alleged rapist (there's some question of what really happened), and he masks his sexual frustration further by trying to assert military dominance over his prisoners. Oshima fumbles again here, playing the movie's climactic moment a little too obviously. Any time a filmmaker shifts into slow-mo to emphasize the important action, they are just asking for trouble. Much of the storytelling in Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence is both clumsy and old-fashioned, with narrative jumps making some crucial plot points come off as out of joint. Also, the musical score by Ryûichi Sakamoto, which features a lot of '80s synthesizer, is dated and anachronistic. I found it distracting.

Thankfully, the acting is uniformly solid, and this allows the material to rise over any bad directorial choices. As a reviewer, I use the word "solid" a lot, and in this case, I really mean it. There is a consistency to the performances in the movie that is almost as level as a cement slab. Conti, Bowie, and Sakamoto are all good, but unremarkable. Only Takeshi Kitano stands out. He is possessed of a more natural screen charisma than the others, and the camera is magnetically drawn to his orbit. It's no surprise he went on to better things.

Original Theatrical Poster

Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence has an impressive final act. The fate of Celliers is macabre, and despite the panting earnestness of the early scenes, Oshima knows that repressed emotions are more effective in this case than any sweaty relief would ever be. Mr. Lawrence is a sad film, one where there is no clear line between right and wrong, and thus no satisfaction for anyone. The melancholy denouement neatly encapsulates all the things the rest of the film touches on: war is destructive, and it causes men to act in ways that are against their nature. The cultures that have been clashing finally get a moment's peace, and they eventually understand each other in some fashion--even if it is only two men, they represent some part of the whole.

Though not a masterpiece, Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence is an intriguing film. Given the current debate over "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" in the United States Senate, there are even political elements to it that are still relevant. It's hard to say if they are any less progressive now then they were nearly thirty years ago. At one point in the movie, Hara says that, to a samurai, there is no gay or straight, there are just men on the battlefield. Why hang yourself up with worries about anything else? It's a code of honor well worth adopting.

This is the first time that Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence has come to any kind of digital disc in the United States, and Criterion does it up right for their Blu-Ray release. The 1080p high-definition transfer (1.78:1 aspect ratio) has lots of impressive detail. Outdoor scenes look especially good, with vibrant colors and a tremendous clarity. You can practically stop and count the blades of grass. Darker scenes have a little more graininess, as do wider shots. This appears to be the nature of how the film was shot, however, as the transitions seem natural. The overall image appears to be very true to the original intent of the filmmakers.

The bilingual soundtrack is presented here as a DTS-HD Master. The stereo mix creates a nice interspeaker balance with the original audio, creating a decent amount of depth even with a simple 2.0 range.

SIDE NOTE: I was actually surprised to find some fan art online for Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, of which the above, by an artist who goes by the moniker Pudding, is the best (original location). Some of it is humorous, some of it a little pervy, most of it done in a manga/anime style. That would suggest the movie has a fairly strong cult following. Use Google image search and nose around for some more if you want.

More surprising is this music mash-up called "Forbidden Young Folks," which combines the vocals from Peter Bjorn & John's "Young Folks" with Ryûichi Sakamoto's melancholy theme from the film.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Sunday, September 19, 2010

CHARADE Revisited on Blu-Ray - #57

[The main body of this review as originally published February 2008.]

"Sixsmith wrings sweat from his handkerchief. 'I saw Charade with my niece at an art-house cinema last year. Was that Hitchcock? She strong-arms me into seeing these things, to prevent me from growing "square." I rather enjoyed it, but my niece said Audrey Hepburn was a "bubblehead." Delicious word.'

'Charade's the one where the plot swings on the stamps?'

'A contrived puzzle, yes, but all thrillers would wither without contrivance.'"

I have to admit, I didn't like Charade the first time I saw it. Advance expectation is a killer of many a good film, and I originally watched the 1963 movie as part of my crawl through the Audrey Hepburn filmography. Being the oft-delayed coupling of Ms Hepburn and Mr. Cary Grant, I went in expecting a lighthearted romantic comedy--which is what I got, at least for half of Charade. The other half, as it turned out, was a Hithcockian thriller with a dark, even violent streak. In my mind, the two clashed in ways I couldn't quite reconcile. Who got all this blood in my peanut butter?

The screenplay for Charade, written by Peter Stone, is a study in incongruities. Mrs. Regina Lampert (Hepburn) and Mr. Peter Joshua (Grant) meet at a mountain resort, trade a few cynical retorts about love and their failed marriages, and essentially start a flirtation in a manner classic to the genre. Like two superheroes meeting for the first time who have to fight before they get along, two lovers in romantic comedies begin swapping acid before they swap spit, and the pleasure comes from watching their defenses crumble. For quite a while, the first words Reggie and Peter exchange were my answering machine's outgoing message. "I already know an awful lot of people and until one of them dies I couldn't possibly meet anyone else." "Well, if anyone goes on the critical list, let me know."

Upon returning to Paris, however, romance is not in the air, mystery is. Regina discovers her apartment empty except for a French police inspector (Jacques Marin). He informs her that her husband sold all of their furniture, absconded with the $250,000 he got for it, and then got himself thrown off a train. The money did not get thrown with him, and it is presumed stolen or missing. When three cartoonish crooks (James Coburn, George Kennedy, and Ned Glass) show up for the late Mr. Lampert's funeral, it becomes clear that it's the latter. In fact, not only are these guys looking for it, but so is the C.I.A. An agent by the name of Bartholomew (Walter Matthau) tells Reggie that her husband was not who he said he was, and that the $250,000 was actually stolen from the U.S. government by the dead man and his army buddies back in WWII. The bad guys will kill her to find it, and the U.S. will basically put her on the hook for it if she doesn't find the dough and return it. There are an awful lot of rocks to get caught between when the world is one big hard place.

Enter Cary Grant to save the day, right? Well, kind of. While Peter does offer to lend a hand, he may not be who he says he is. In fact, he may not be multiple people he says he is. So, while he romances Regina, we never know whose side he's really on, nor if he's the one responsible for all the bodies that are starting to pile up around them.

There is much for fans of classic romance to catch the vapors over in Charade. Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant have a marvelous natural rapport, and the scenes where they just clown around with each other are priceless. Director Stanley Donen has a graceful comic touch, and he gives his stars ample opportunity to do what they do best. A walk along the Seine, with its self-referential jokes about An American in Paris [review], which starred Donen's former creative partner Gene Kelly, is a wonderful display of comedic timing. As soon as Peter responds to one thread of conversation, Reggie switches to another, leaving the befuddled man to constantly catch up. The self-effacing charm that always served Cary Grant is well honed at this point, and the actor not only weathers jokes about his age, but requested them in order not to look like an old lecher chasing a young gamine through the City of Lights. These get some of the best laughs in the movie. (If only someone had taken the air out of Gary Cooper's tires in the same way before he courted the young actress in Love in the Afternoon .)

.)

Yet, there is also some squeamish violence to contend with in the plot. Despite Lampert's old army buddies being overdrawn caricatures--Coburn the boorish Texan, Glass a nebbish, Kennedy a one-handed monster--when they go to work, Donen doesn't soften any of their blows. When they confront Reggie alone, there is a real feeling of sexual threat, and when they engage in fisticuffs with Peter, the violence is deadly. A rooftop tussle with the hook-handed Kennedy leaves a big, bleeding gash on Peter's back, and when the crooks start getting themselves killed, the manner of the murders is uniformly gruesome, escalating to James Coburn being trussed up with a clear plastic bag over his head, the death grimace of his suffocation visible through the Ziploc.

The sweet stuff was so sweet and the bitter business so bitter, I couldn't make sense of why Donen and Stone had chose to put them together in this way. Was it just the changing times, a need to update and compete? Probably not. Though change was a-coming, the censorship boards had not yet gone completely lax, and the violent turnaround of American movies was a couple of years off. While Charade was maybe testing those waters, it wasn't done out of competition, but a deeper thematic concern.

Charade is a tapestry of lies that extends beyond assumed identities and crime. In this narrative, relationships have also become charades. The Lamperts are in an empty marriage that is only saved from divorce by the husband's untimely death. As it turns out, the wife didn't know her husband at all, and what she is discovering is that love is not as simple as it once was. Can we really know anybody? Is courtship anything more than donning a mask to convince the person we desire that we are someone to be desired, as well?

Even beyond that, though, moviemaking is a charade. For decades, the audience had been conditioned to view thrillers and romantic comedies alike without considering that any real-life equivalent of these fictions would carry with it real-life consequences. In a manner that could be just as startling as anything coming out of 1960s France and the British Kitchen Sink school, or still to come with the young turks of new American cinema, Stanley Donen was exposing the false bottom of the Hollywood technique. Realizing this gives new meaning to the climactic showdown, where the real killer chases Reggie into a traditional theatre and finds himself on the business end of a trapdoor. There is nothing under the stage, you see, the boards these players tread are not rock solid, and their actions are not to be believed. It's like the fake-out with the water pistol in the opening scenes, but played out for 114 minutes

This was the crucial logic that I missed in the cloud of my initial expectations for Charade, a mist that had to be cleared for me to see the film for what it really was. Once I figured out the reason for the juxtaposition of love and violence, comedy and crime, I could see the greater meaning the filmmakers were trying to convey. Charade is not a subversion of silver-screen romance, but an affirmation of it. Love isn't knowing exactly what you are getting, but extending a level of trust that tells the other person that he or she is worth the risk of being lied to. When the bullets are flying, Peter extends his hand to Reggie, and she asks why she should place his faith in him. He tells her there is no logical reason on Earth for her to do so, and he's right, there isn't. Thankfully, emotion is eschewing logic to follow instinct, and it means all the more that Reggie is able to love again when there is no good explanation for it. She simply follows her heart, and the charade dissolves.

Criterion has brought Charade to the Blu-Ray format with a new high-definition digital transfer, 1080p, at the original 1.85:1 aspect ratio. The restoration is impressive. Colors are excellent, with realistic skin tones and vibrant hues (pay special attention to the reds to see what I mean.) Their is a pleasant, natural grain to the overall image texture. It can sometimes make the picture look a little soft, especially in extreme close-ups, but not so you'd notice once you are caught up in the story. What is the most remarkable is the depth of field. Details are clear in complicated close quarters like the hotel rooms, and there is tremendous clarity when Cary Grant and George Kennedy are fighting on the rooftops. You can see the whole city behind them, and the neon signs glow with real electricity. In the subway, you can see the shine on the wall tiles contrasted with the texture of the cement floor. I have seen three or four different versions of Charade, and I swear, it's never looked like this.

The BD of Charade comes in a similar package to the previous DVD releases, though with an improved cover image with a vintage movie poster design. The booklet inside is likely the same as the 2nd edition, reprinting the Bruce Eder essay that has been part of the deal since Criterion's first 1999 release. (I never did purchase the upgrade from a couple of years ago, so I am guessing a little.)

Also carried over is the excellent commentary with Stanley Donen and screenwriter Peter Stone. I love listening to Stanley Donen. He's just such a bright guy--in every sense of the word.

The original theatrical trailer is also included.

Missing from previous editions is the section showcasing the filmography of Stanley Donen, which was basically a text-based, illustrated biography. (The 1999 disc had a similar feature for Peter Stone that I believe was dropped from the later reissue.)

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

"Sixsmith wrings sweat from his handkerchief. 'I saw Charade with my niece at an art-house cinema last year. Was that Hitchcock? She strong-arms me into seeing these things, to prevent me from growing "square." I rather enjoyed it, but my niece said Audrey Hepburn was a "bubblehead." Delicious word.'

'Charade's the one where the plot swings on the stamps?'

'A contrived puzzle, yes, but all thrillers would wither without contrivance.'"

- from Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

I have to admit, I didn't like Charade the first time I saw it. Advance expectation is a killer of many a good film, and I originally watched the 1963 movie as part of my crawl through the Audrey Hepburn filmography. Being the oft-delayed coupling of Ms Hepburn and Mr. Cary Grant, I went in expecting a lighthearted romantic comedy--which is what I got, at least for half of Charade. The other half, as it turned out, was a Hithcockian thriller with a dark, even violent streak. In my mind, the two clashed in ways I couldn't quite reconcile. Who got all this blood in my peanut butter?

The screenplay for Charade, written by Peter Stone, is a study in incongruities. Mrs. Regina Lampert (Hepburn) and Mr. Peter Joshua (Grant) meet at a mountain resort, trade a few cynical retorts about love and their failed marriages, and essentially start a flirtation in a manner classic to the genre. Like two superheroes meeting for the first time who have to fight before they get along, two lovers in romantic comedies begin swapping acid before they swap spit, and the pleasure comes from watching their defenses crumble. For quite a while, the first words Reggie and Peter exchange were my answering machine's outgoing message. "I already know an awful lot of people and until one of them dies I couldn't possibly meet anyone else." "Well, if anyone goes on the critical list, let me know."

Upon returning to Paris, however, romance is not in the air, mystery is. Regina discovers her apartment empty except for a French police inspector (Jacques Marin). He informs her that her husband sold all of their furniture, absconded with the $250,000 he got for it, and then got himself thrown off a train. The money did not get thrown with him, and it is presumed stolen or missing. When three cartoonish crooks (James Coburn, George Kennedy, and Ned Glass) show up for the late Mr. Lampert's funeral, it becomes clear that it's the latter. In fact, not only are these guys looking for it, but so is the C.I.A. An agent by the name of Bartholomew (Walter Matthau) tells Reggie that her husband was not who he said he was, and that the $250,000 was actually stolen from the U.S. government by the dead man and his army buddies back in WWII. The bad guys will kill her to find it, and the U.S. will basically put her on the hook for it if she doesn't find the dough and return it. There are an awful lot of rocks to get caught between when the world is one big hard place.

Enter Cary Grant to save the day, right? Well, kind of. While Peter does offer to lend a hand, he may not be who he says he is. In fact, he may not be multiple people he says he is. So, while he romances Regina, we never know whose side he's really on, nor if he's the one responsible for all the bodies that are starting to pile up around them.

There is much for fans of classic romance to catch the vapors over in Charade. Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant have a marvelous natural rapport, and the scenes where they just clown around with each other are priceless. Director Stanley Donen has a graceful comic touch, and he gives his stars ample opportunity to do what they do best. A walk along the Seine, with its self-referential jokes about An American in Paris [review], which starred Donen's former creative partner Gene Kelly, is a wonderful display of comedic timing. As soon as Peter responds to one thread of conversation, Reggie switches to another, leaving the befuddled man to constantly catch up. The self-effacing charm that always served Cary Grant is well honed at this point, and the actor not only weathers jokes about his age, but requested them in order not to look like an old lecher chasing a young gamine through the City of Lights. These get some of the best laughs in the movie. (If only someone had taken the air out of Gary Cooper's tires in the same way before he courted the young actress in Love in the Afternoon

Yet, there is also some squeamish violence to contend with in the plot. Despite Lampert's old army buddies being overdrawn caricatures--Coburn the boorish Texan, Glass a nebbish, Kennedy a one-handed monster--when they go to work, Donen doesn't soften any of their blows. When they confront Reggie alone, there is a real feeling of sexual threat, and when they engage in fisticuffs with Peter, the violence is deadly. A rooftop tussle with the hook-handed Kennedy leaves a big, bleeding gash on Peter's back, and when the crooks start getting themselves killed, the manner of the murders is uniformly gruesome, escalating to James Coburn being trussed up with a clear plastic bag over his head, the death grimace of his suffocation visible through the Ziploc.

The sweet stuff was so sweet and the bitter business so bitter, I couldn't make sense of why Donen and Stone had chose to put them together in this way. Was it just the changing times, a need to update and compete? Probably not. Though change was a-coming, the censorship boards had not yet gone completely lax, and the violent turnaround of American movies was a couple of years off. While Charade was maybe testing those waters, it wasn't done out of competition, but a deeper thematic concern.

Charade is a tapestry of lies that extends beyond assumed identities and crime. In this narrative, relationships have also become charades. The Lamperts are in an empty marriage that is only saved from divorce by the husband's untimely death. As it turns out, the wife didn't know her husband at all, and what she is discovering is that love is not as simple as it once was. Can we really know anybody? Is courtship anything more than donning a mask to convince the person we desire that we are someone to be desired, as well?

Even beyond that, though, moviemaking is a charade. For decades, the audience had been conditioned to view thrillers and romantic comedies alike without considering that any real-life equivalent of these fictions would carry with it real-life consequences. In a manner that could be just as startling as anything coming out of 1960s France and the British Kitchen Sink school, or still to come with the young turks of new American cinema, Stanley Donen was exposing the false bottom of the Hollywood technique. Realizing this gives new meaning to the climactic showdown, where the real killer chases Reggie into a traditional theatre and finds himself on the business end of a trapdoor. There is nothing under the stage, you see, the boards these players tread are not rock solid, and their actions are not to be believed. It's like the fake-out with the water pistol in the opening scenes, but played out for 114 minutes

This was the crucial logic that I missed in the cloud of my initial expectations for Charade, a mist that had to be cleared for me to see the film for what it really was. Once I figured out the reason for the juxtaposition of love and violence, comedy and crime, I could see the greater meaning the filmmakers were trying to convey. Charade is not a subversion of silver-screen romance, but an affirmation of it. Love isn't knowing exactly what you are getting, but extending a level of trust that tells the other person that he or she is worth the risk of being lied to. When the bullets are flying, Peter extends his hand to Reggie, and she asks why she should place his faith in him. He tells her there is no logical reason on Earth for her to do so, and he's right, there isn't. Thankfully, emotion is eschewing logic to follow instinct, and it means all the more that Reggie is able to love again when there is no good explanation for it. She simply follows her heart, and the charade dissolves.

Criterion has brought Charade to the Blu-Ray format with a new high-definition digital transfer, 1080p, at the original 1.85:1 aspect ratio. The restoration is impressive. Colors are excellent, with realistic skin tones and vibrant hues (pay special attention to the reds to see what I mean.) Their is a pleasant, natural grain to the overall image texture. It can sometimes make the picture look a little soft, especially in extreme close-ups, but not so you'd notice once you are caught up in the story. What is the most remarkable is the depth of field. Details are clear in complicated close quarters like the hotel rooms, and there is tremendous clarity when Cary Grant and George Kennedy are fighting on the rooftops. You can see the whole city behind them, and the neon signs glow with real electricity. In the subway, you can see the shine on the wall tiles contrasted with the texture of the cement floor. I have seen three or four different versions of Charade, and I swear, it's never looked like this.

The BD of Charade comes in a similar package to the previous DVD releases, though with an improved cover image with a vintage movie poster design. The booklet inside is likely the same as the 2nd edition, reprinting the Bruce Eder essay that has been part of the deal since Criterion's first 1999 release. (I never did purchase the upgrade from a couple of years ago, so I am guessing a little.)

Also carried over is the excellent commentary with Stanley Donen and screenwriter Peter Stone. I love listening to Stanley Donen. He's just such a bright guy--in every sense of the word.

The original theatrical trailer is also included.

Missing from previous editions is the section showcasing the filmography of Stanley Donen, which was basically a text-based, illustrated biography. (The 1999 disc had a similar feature for Peter Stone that I believe was dropped from the later reissue.)

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Labels:

audrey hepburn,

blu-ray,

cary grant,

stanley donen

Saturday, September 18, 2010

BIGGER THAN LIFE - #507

"You're a poor substitute for Abraham Lincoln."

That may have just leaped to the head of the pack for the best denouement of any movie.

It's rare that a film with a reputation for being nuts is as nuts as everyone says it is, particularly when said jar of cashews is nearly 50 years old. But Nicholas Ray's 1956 subversion of suburbia Bigger Than Life is just as mixed-up as I've always heard, with James Mason's towering title performance worthy of getting his face carved into the Mount Rushmore of acting. Right next to Honest Abe.

Bigger Than Life starts out normal enough. At first glance, you'd think it was a light school dramedy. It opens as the day ends at an elementary school somewhere in a faceless neighborhood in America. Smiling children bound out the doors, and the teachers pack up for the day. There is James Mason sitting behind his desk, inhabiting the body of Ed Avery, a jocular teacher with a jaunty accent who isn't afraid of flirting with the cute younger woman in the classroom next to him. He also trades japes with his buddy Wally, the gym teacher with a strange taste in head gear (a young Walter Matthau, already typecast, it seems). It's all terribly normal. It's like Ed asks his kid Richie (Christopher Olsen) when peeking in on his television habits: "Doesn't this bore you? It's always the same story."

The first montage is barely over before the cracks begin to show, but even those start normal enough. To supplement his salary, Ed is secretly working as a taxi dispatch, lying to his wife and claiming he has administrative meetings to attend. He's also hiding the fact that he's having pains in his gut. Ulcers from stress, maybe? It doesn't matter. Ed and his wife, Lou (Barbara Rush), are hosting a dinner party for friends and co-workers. It's only after that the pain becomes unbearable. Ed collapses. He ends up in the hospital, and it's just in the nick of time. Whatever Ed has, it's nearly fatal, and after a battery of invasive tests, Ed's doctor (Robert Simon) decides the new drug cortisone is the only way to treat this malady.

It works. Ed is back on his feet, and he's got a new lease on life. Back at work, he's got a spring in his step. At home, he's feeling randy. He insists on taking Lou out and buying her a new dress. He plays football indoors with Richie (this was before "The Brady Bunch" warned us of such things). He's also strangely aggressive, mouthing off and throwing his weight around, and temperamental. Richie and Lou notice it right away, but when they question it, Ed doesn't like it.

Long story short, Ed is addicted to his prescription meds and they are making him act this way. Bigger Than Life is quite possibly the first ever movie about abusing pills in Middle America, and unlike the countless Lifetime movies that would follow in its wake, it surprisingly is about a man getting hooked on the poppers, not a bored housewife. Once Ed is out of the hospital, Nicholas Ray and his pair of writers, Cyril Hume and Richard Maibaum, chronicle the breakneck pace of Ed's breakdown. His skull is a pressure cooker, cranking the heat steadily until the crazy is coming out his ears. Apparently, the story began as a New Yorker article, so there must be some basis in fact here, but who cares? Bigger Than Life gets just as cracked as its main character, and it's fantastic to watch.

Mason is a powerhouse as Ed, slowly losing his marbles and getting the jones for his prescriptions. He never overdoes it, there is no slurred speech or anything too comical in how he presents himself. Instead, you can see his mind is burning fuel at a rapid rate, and the conflagrations emerge as all kinds of socially improper behavior and opinions, before settling into dark places when the tank gets empty. Bigger Than Life has a black sense of humor, and there are many laugh-out-loud lines. It ranges from Ed mistakenly thinking that a hypodermic to his sternum means his buttocks ("Sorry," he says when corrected, "I did four years in the navy.") to more abstract jokes on modern psychology. At the school, a young boy shows Ed a twisted painting he has done, and when Ed wonders if the black and red smudge is a thunderstorm, the kid says, "This is a man. He's just mad at his mother." It's even more devilish now, because the kid was Jerry Mathers, who went on to play the Beaver. Youth icons are not safe in Bigger Than Life. Presumably little Richie's red jacket is Nicholas Ray poking fun at himself. He put James Dean in one just like it a year before in Rebel Without a Cause

Bigger Than Life is not just about gonzo parodies, however; Ray is getting at something about the modern condition, the way we compartmentalize and isolate ourselves in our boxed-off neighborhoods, with psychology and pharmaceuticals and the like. His canvas is the 1950s, but it's still relevant. At Ed and Lou's dinner party, one of the guests tells an anecdote about how she feels she is faced with two options: having a baby or buying a new vacuum cleaner. Do you want a life in the traditional sense, or do you want technological convenience?

Likewise, suburbia itself is a façade. Lou tries to keep the secret of Ed's drug-fueled kookiness, but it's hard to be real when the milkman can walk by at any moment. And he literally does; the scene juxtaposes the quaint Norman Rockwell image of American life with the hush-hush perversions each person is trying to hide. It's dangerous to challenge the illusion--and that's just what Ed does. He rails against everything, including family and Christian morality ("God was wrong!" he shouts at one point, and shortly after, very nearly stabs a Bible). At a PTA meeting, he declares that childhood is a congenital disease, and education cures it. Adulthood and reason weeds out the primal impulse. It's ironic, though, because cortisone is giving Ed back his. He's riding entirely on Id and instinct. He struts around like a werewolf--though Conan O'Brien's "Coked-Up Werewolf" more than Jacob Black--or maybe Renoir's Hyde-like Mr. Opale from The Doctor's Horrible Experiment [review]. He's a real creep!

The colorful sets and the photography of Joe MacDonald (Niagara

No visitors.

The thing is, it's Lou that eventually has to take charge and fix things. The final act of Bigger Than Life very nearly turns into a slasher movie. Ed holds scissors over his son, an implied threat that he then voices as very real. Lou tiptoes around the house, scared of attracting the beast's attention, surreptitiously calling for help over the phone and hoping to sneak out. She uses her wiles to placate him briefly, buying enough time to let others intervene. Back at the hospital, the doctors try to cut her out, suggesting that, as a woman, she can't control her emotions. Throughout Bigger Than Life, people have said similar, and Lou has even been called an idiot. Yet, she's always the one who has to clean up for her manic husband, who has to take charge and stay calm. In the end, she's the only one who believes in him. Her expression of faith in all the things he's denied, and her rejection of the chemical faith the presiding powers want her to have, ends up being the Averies' salvation.

Again, Nicholas Ray borrows from outside the sudsy genre. His brightly colored family drama ends like a horror movie. The sun rises, the evil passes, Scarlett O'Hara standing outside Tara and swearing to never go off her rocker again. It's amazing what Ray has done. He has taken all the tropes of the Hollywood melodrama, the image of the American family, the colorful palette of Technicolor, and the epic sprawl of Cinemascope, and he has created a darkly subversive movie. Though illuminating the hidden shadows of suburbia is a common theme these days (especially post-Blue Velvet

But Ray and his writers were putting the iniquity right there in the center of it all. The villain was one of the best of us, a well-spoken teacher, a trusted individual. And it was all the trappings of this kind of life, everything he worked two jobs to earn, that did it to him. If families in 1956 did happen to catch a matinee of Bigger Than Life, daddy must have gotten some strange looks on the way home. Which is what made the film so startling in its rebellion, the way it plants these radical ideas. I would guess its failure on release was not because it was unbelievable, but because it was too believable. Just like Wilder's Ace in the Hole [review], it told America too much about itself, and so America rejected it.

Except now we know that Wilder and Ray were both right, that America should have been scared; that they are more right now than ever is the scariest part of all.

Watch the trailer for Bigger Than Life.

Labels:

hitchcock,

Nicholas Ray,

renoir,

sirk,

wilder

Friday, September 10, 2010

NIGHT TRAIN TO MUNICH - #523

Rex Harrison is a glorious bastard. In Carol Reed's 1940 war movie Night Train to Munich, the all-too-British actor dons a Nazi uniform and waltzes through enemy lines with nothing but a false letter of introduction and an uncommon sense of bravado. Lucky for him, unlike Michael Fassbender in Quentin Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds [review], he doesn't have to worry about getting the German accent right. Everyone here speaks the Queen's English regardless of national origin.

Which was kind of confusing at the outset, I must admit. Though the heroine of our tale, Anna Bomasch (Margaret Lockwood), and her father (James Harcourt) are first seen in Prague, I didn't get right away that they were Czech. And you really can't fault the Nazi officer later in the picture who doesn't realize that Charters and Caldicott (Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne) are proper British gentleman. Everyone in Carol Reed's version of Europe is!

Night Train to Munich is a quaint propaganda thriller made while England's involvement in the war was still fresh. Writers Sidney Gilliat and Frank Launder, working from a story by Gordon Wellesley, set their script a year prior to the production, on the eve of France and the UK getting into the combat. It portrays an England that was ready for anything, their eye firmly and suspiciously trained on their aggressive neighbors to the west. The intention of the film was similar to that of Powell & Pressburger's The 49th Parallel [review]: to bolster and inspire through popular entertainment. Hollywood made similar movies throughout the war, though with a far toothier American demeanor--most of our heroes followed an arc that took them from cynical loner to righteous patriot in 90 minutes. The British film industry, on the other hand, gave us upright citizens more than eager to engage in what was right. As a result, a lot of their wartime films, including Night Train to Munich, are far more obvious in their mission.

Though, to be fair, Night Train manages to scrounge some pretty good nail-biting scenarios out of all these good intentions. The personnel involved knew their way around a suspense picture. Gilliat and Launder previously wrote another mystery set on a train, Hitchcock's early masterpiece The Lady Vanishes [review], a film that also starred Lockwood and introduced us to the droll supporting players Charters and Caldicott, the sort of fellows who apparently only vacation in trouble spots. (Tip to time travelers: if they are ever on your train, get off!) And, of course, Night Train's director Carol Reed would famously master the post-War thriller with films like The Third Man [review] and the less-known but equally intense Odd Man Out

Dr. Axel Bomasch is a Czech scientist developing a particularly strong new alloy that will be perfect for armored vehicles. When the war comes to Prague, he and his associates high tail it for England. The only hitch is that his daughter, Anna, is arrested at their house just as she is heading for the getaway plane. She is sent to a prison camp, where she meets the stalwart schoolteacher Karl Marsen (Paul Henreid, later to play the freedom fighter Victor Laszlo in Casablanca

I like that the love triangle in Night Train to Munich continues even after Karl is revealed to be a Ratzi. I like even more how it's done. How very British that so much of it is unspoken, and Karl's feelings in particular are never expressed. He is made a cuckold before he ever gets the chance to make a move, the fate of a man who chose his job over the girl. When he nabs the Bomasches and takes them back to the Reich, Gus switches places with him by going undercover as a Nazi officer who claims to have sway over Anna because they once had an affair. When he is given permission to spend the night romancing her in her (scandal!) hotel room, Karl is positively seething with unspoken anger. Not only is this cocky rival coming in and doing a job he can't (convincing the girl to convince her father to give up his secrets), but now there is a love affair, too? Little does he know that it's a pretend one, but then, Rex Harrison is such a wily cassanova, that's actually how he works his mojo. If you make the lady pretend you're irresistible often enough, she'll realize you really are!

Once these wheels are in motion, the group eventually ends up on the titular train, and that's where they also run into the comedy duo of Charters and Caldicott, followed by the eventual chase through Munich, including the scenes on the sky trams depicted on the cover of the DVD (the awesome artwork smartly modeled after old travel posters). The shootout in the mountains is a marvelous action sequence, and Reed and cameramen Otto Kanturek do a tremendous job of re-creating the majesty of the Swiss Alps via models and matte paintings (also note the cool model work when Anna and Karl escape the concentration camp). By this point, Night Train to Munich has transcended its propaganda origins and turned into a cracking movie.

If I have one complaint about Night Train, it's probably that Margaret Lockwood is an undervalued member of the team. Both Harrison and Henreid are so good in their roles and have such meaty material to wrestle with, it sometimes feels like the girl they are fighting over is lost in the process. Gus does try to make Anna an active part of the scheme, but the writers don't go far enough with it. Margaret Lockwood is charming and very pretty and so more than capable, and Anna has a plenty of motivation for being a killer lady spy, but the boys in charge are far too willing to let their fellows take control. Particularly once Radford and Wayne join the escape party, their banter practically shoves any conversation between Anna and Gus off the screen.

Still, that's a minor problem in what is otherwise some damn fine light entertainment. Thought not as deep as Reed's later movies--even if we do get a few scenes where his use of shadows suggest the noir to come--it's actually a lot more fun. His light touch with the action and the humor more than makes up for any heavy hand in the underlying message, and all told, Night Train to Munich makes for an enjoyable return trip to the matinees of yesterday.

Sunday, September 5, 2010

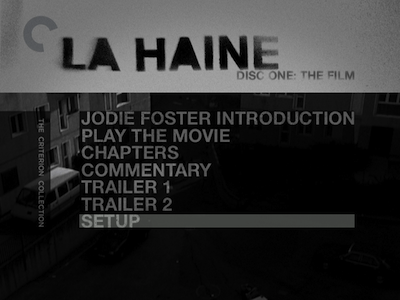

LA HAINE - #381

The 1995 French film La haine chronicles 24 hours in the life of a French ghetto the day after a good portion of its population rioted and looted in protest of police brutality against an Arab youth. The fires have mostly gone out, but tensions are still high. The cops are bruised and itching for payback, shop owners and others who had property damaged in the conflagration wonder what it was all for, and the rioters wait to hear if the victim will pull through in case they have to rise up again.

La Haine (Hate) was written and directed by Mathieu Kassovitz in response to an incident similar to the one he centers his film around--a personal tragedy in which a friend of his died in police custody. For the movie, he decided to turn his camera on a trio of friends who each represent a significant portion of those marginalized in France's projects (known as banlieue). The motormouthed schemer Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui), the pensive boxer Hubert (Hubert Koundé), and the would-be gangsta Vinz (Vincent Cassel) are Arab, black, and Jewish, respectively. They are faced with institutionalized racism, leaving them with limited options and limited means. Culturally, they look outside France to America, and adopt the music and fashion of the hip-hop scene as expressions of their anger and frustration.

All three boys have something they want out of their day. Saïd wants to collect some money owed him, Hubert wants a way out of the wasteland, and Vinz wants to gain a reputation for himself. In a plot wrinkle right out of Kurosawa's Stray Dog, one of the riot cops lost his revolver in the melee, and Vinz is the one who found it. If Abdel, the boy in the coma, dies, Vinz will use the gun to kill a "pig," taking one of their ranks as retribution for the life they took. Vinz doesn't have any clear conception of a greater ideology. In fact, Kassovitz makes a running gag out of the confused philosophy that runs through modern culture. Expressed via jokes and anecdotes, most of the moral conundrums heard throughout La haine seemingly have no greater meaning. The only one that pays off is the one that opens the movie, the story of a falling man trying to maintain his optimism as he plummets to Earth. Hubert picks up this riddle. As the boxer who has decided he doesn't want to fight anymore, he can see the wisdom in its punchline: it's not about how you fall, it's about how well you land.

For an electrified 97 minutes, La haine follows these boys through their neighborhood, where they talk to their cohorts and tussle with local law enforcement, and then on a train to Paris. There, they become stranded for a night after Saïd's connection doesn't pay out. Killing time, they terrorize an art gallery, try to steal a car, and get in a brawl with some racist skinheads. Political indignation turns to "ghetto malaise," as the gallery owner phrases it. Not that a more harsh reality isn't always waiting for them; Hubert and Saïd also get a taste of actual police brutality. Fittingly, Vinz spends the same time they are in jail watching a violent movie. Like Jean-Paul Belmondo before him, this French gangster imagines himself as a rebel straight off the silver screen. Only now instead of worshiping Humphrey Bogart, our anti-hero looks up to Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver

Yet, it's not Scorsese that Kassovitz's incendiary masterpiece most resembles, it's Spike Lee's 1989 picture Do the Right Thing. Lee's film is the story of a day in the life of a New York neighborhood in the 24 hours leading up to a riot, not the period after. Both Do the Right Thing and La haine exist in a rarefied space, where there is seemingly no before or after, only now. Both trade elements of realism for abstraction in order to make their point, and both use an electrified visual style to give their parables life. Movement is important in these movies: the characters keep moving, and so does the camera. Kassovitz and director of photography Pierre Aïm borrow Ernest Dickerson's energetic use of all four corners of the image frame. They prowl around their scenes like an animal on the hunt, cajoling their characters into action by pushing in fast, rapidly removing the space between viewer and subject, leaving them nowhere else to go. Both films also use hiphop as the aural companion to the visuals. La haine replaces Mister Señor Love Daddy and Public Enemy with French DJ Cut Killer, who in one scene splices together KRS-One's "Sound of Da Police" with Edith Piaf and sends the music soaring out over his friends and neighbors.

Where Do the Right Thing and La haine differ significantly is in color palette. Whereas Lee and Dickerson cranked the color way up as a representation of the summer heat that was causing tempers to flare, Kassovitz and Aïm pull back. La haine is shot in black-and-white with occasional tinting--mostly hints of green and brown--a choice that suggests many things. For one, black-and-white is chillier in temperature, befitting a situation where everyone is trying to keep their cool. It also equalizes the characters, taking out the differences in color that they see in one another and having the audience gaze up them in a way that asks us to judge them for something besides their skin tone. By evoking the look of older films, it also suggests that racism and injustice is a problem as old as cinema itself. This creates an added layer of tension, as we assume at some point the color will explode all over the screen, its return all but inevitable.

I picked La haine for review because I wanted to see a young Vincent Cassel at work after having recently watched the two-part Mesrine biopic [review 1, review 2]. Nearly 15 years separate the two films, and Cassel was just as intense back then as he is now. Whereas Jacques Mesrine is all outward bombast buoyed by a sociopathic self-assurance, Vinz's posturing is undercut by his lack of confidence. The boy seethes with a rage that he's dying to express, but he doesn't understand it. Both Mesrine and Vinz will go off, but Mesrine unleashes knowing the full consequences of his attack; Vinz has no idea what is waiting for him. Cassel finds a sweet spot where he balances the teen's romantic visions of thug life with the blank wall he erects to prevent the outside world from teaching him anything.

Cassel is phenomenal in La haine, but it's unfair that he gets all the attention. The other actors in the ensemble are just as good, just as natural. I assume Kassovitz had them us their own names because it made them closer to their characters, and they definitely are believable in how they walk the walk. Saïd Taghmaoui in particular can also talk it. His tongue is rarely still, and he perhaps has the most important role in that he serves as the connective tissue between Vinz and Hubert. They each want to go in opposite directions--Vinz toward the blaze of hate, Hubert toward someplace more peaceful--but Saïd could go either way. The other two boys are caught in a cycle that is beyond their control, whereas Saïd is the one who can walk away a different person.

And he may also be the only one who can walk away. Kassovitz shows life in La haine as a constant circle. At one of the many points when Hubert is frustrated with Vinz, he tells him that had he not dropped out of school, Vinz would know that hate only breeds further hate. Knowledge of the disease is not the same as knowing what the cure is, however; Kassovitz's depiction of the world is such that there is no curbing the hatred. It's so deep in the system, there seems to be no way to shock ourselves out of it. Each death demands another death. If Abded dies, Vinz will have to kill a police officer, and so on. It connects back to one of the other stories told in the middle of the movie, about the man chasing a train with his pants undone. Every time he takes a hand off his waistband to grab onto the train, the pants fall and he trips. The train won't stop, he'll never catch it. When the boys ask what happened to him, the storyteller says he eventually froze to death.

The train keeps moving, and we're all out in the cold.

Labels:

godard,

kurosawa,

Mathieu Kassovitz,

scorsese,

Spike Lee

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)