It was a big movie month for me, despite it being pretty dead in the cineplexes. The Portland International Film Festival pretty much waylaid three weeks for me. I posted my capsule reviews I wrote for the Portland Mercury over on my main blog, and you can read all the full-length reviews I did for Criterion Cast over on my author's page there.

Thanks to both venues for hosting me!

Now, on to the regular pieces...

IN THEATRES...

* Barney's Version, an ambitious literary adaptation that can't bear the narrative weight. Fine performances by Paul Giametti, Dustin Hoffman, and Rosamund Pike at least make it watchable.

* And Everything is Going Fine, Steven Soderbergh's tribute to the late Spalding Gray. Playing the NW Film Center this weekend.

* Sanctum, boring in all three dimensions.

ON DVD/BD...

* America America, Elia Kazan's remarkable epic story of one boy trying to get from Turkey to America.

* An Affair to Remember, Deborah Kerr and Cary Grant in a romance that never loses its passion.

* Bambi: Diamond Edition, a fantastic release of one of Disney's most impressive movies, bringing this animated classic into the technology of the 21st century brilliantly.

* Burlesque, revisiting one of my favorite reviews from last year now that the movie is out on Blu-Ray and DVD.

* Futureworld, a sort of dull 1970s vision of a theme park future.

* Guest of Cindy Sherman, a documentary made by a narcissist who can't handle that his coattail ride doesn't come with its own coat. I got some particularly juicy hate mail for this review since the piece could be considered as a personal attack on the filmmaker. I stand by the assertion that if you're going to be the subject of your own movie and present yourself and your activities as some kind of plea for sympathy or even admiration, then you erase the line between art and artist. You are the art. This has been an ongoing topic of mine. I refer back to my review of Tarnation, written for this blog back in 2005. Feel free to post your thoughts on the subject below. I think it's an interesting topic worthy of discussion.

* Mesrine: Killer Instinct, the first part of last year's great French gangster epic.

* Thelma & Louise: 20th Anniversary Edition: It's still fun to hit the road with Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis. Directed by Ridley Scott.

* Unstoppable, the other Scott brother's recent film about an out of control road trip is also a pretty damn good time.

Monday, February 28, 2011

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

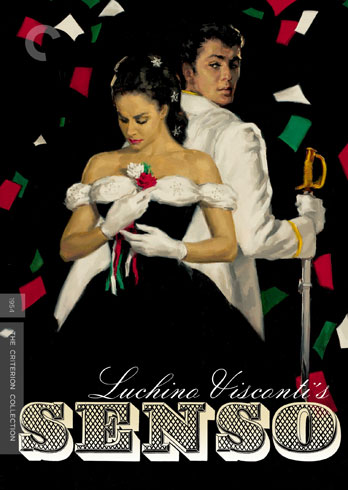

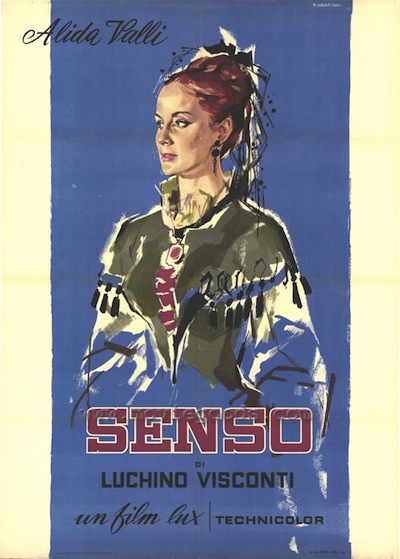

SENSO (Blu-Ray) - #556

Senso is one of those film's with a history that is nearly as checkered and tragic as any of the melodrama that it depicts onscreen. Released in 1954, Luchino Visconti's colorful tale of love and betrayal in 19th-century Italy was met with scorn by Italian critics who disliked its politics and felt that Visconti had strayed too far from the Neorealist movement he had helped create. Also, despite featuring romantic leads who had previously had success in hit films--Farley Granger in Strangers on a Train

My major exposure to it was through Martin Scorsese, who talked about Visconti at length in his documentary My Voyage to Italy

The title Senso pretty much translates as what it sounds like: "sense." Visconti's film is certainly designed to provoke the senses, particularly sight and hearing, the two fundamental ways in which we enjoy cinema. Senso is a masterfully constructed film, with opulent, expansive sets and a bold soundtrack that, in addition to its own evocative music, opens with a selection from a Verdi opera. These early scenes, set in a Venetian theatre, use the performance as a backdrop for our introduction to the movie's central relationships and conflicts. At the time of the film, Italy was not a whole country, and Venice was under the occupied rule of Austrian forces. When a nationalistic outburst causes an uproar amongst the split crowd, Austrian officer Franz Mahler (Granger) exchanges words with patriotic activist Roberto Ussoni (Massimo Girotti). Their argument ends in the challenge of a duel. When Roberto's cousin, the Countess Livia Serpieri (Valli), attempts to intervene on his behalf, an unlikely relationship between her and the enemy soldier begins to foment.

These happenings are surely operatic unto themselves, but Visconti's staging leaves no question as to the emotional tenor of his cinematic undertaking. There is a trifold effect in these scenes. There is the image of the stage production, with its semi-realistic but clearly fake sets; there is the "reality" in front of it, and the far more convincing illusion of Visconti's vision of Italy; and then there is the audience watching Senso, accepting its reality in the way the fictional characters accept the Verdi, knowing it is a concocted vision and yet choosing to go along regardless. All fiction has some kind of layered structure--a world within a world, objects within an object, be it words in a book (Senso is based on a novella by Camillo Boito) or a series of images captured on a DVD. Visconti wants to remind his audience up front that they are to be witness to a heightened experience. He was a firm believer in melodrama and its power to stoke the passions of the audience consuming it, and this set-up prepares the viewer to take it all in, the way a lavishly illustrated menu prepares them for a fantastic meal.

The duel that Livia fears never happens, though Roberto doesn't escape punishment. His public denouncing of the Austrians gets him a year in exile. Though she is sure that Franz is behind it, Livia is seduced by the man in uniform, and the two begin having an affair. It is interrupted by the onset of war, as Italy pushes to expel the invaders. This places Livia in a difficult position between the love of her country and her romantic feelings for Franz. Seeing him is risky, and she further tempts damnation by helping him find a way to escape the dangers of combat.

The performances by Valli and Granger are interesting. They are as finely mannered and sculpted as the magnificent sets in which they perform. Valli is a handsome woman with a strong physical presence. She carries herself as befitting a lady, but there is an intensity always apparent, smoldering just beneath her good manners and dignity. As Senso progresses, this comes out more and more, and Valli's performance grows more fiery as madness takes over. The word "sense" doesn't just mean the five physical senses, but mental as well. Our "sense," common or otherwise, is also our mind, our wits, and our sanity. Senso is a film about taking leave of one's senses. Farley Granger's performance also blossoms as the story grows more hysterical. Franz, too, has been holding back, but in a more dishonest manner than Livia's sense of propriety. As he reveals who he truly is, his wickedness borders on dementia.

Much of Senso takes places indoors, in high-ceilinged mansions full of amazing art and fancy furniture. These are fulsome settings for the selfish rendezvous of these ill-fated lovers to play out. In these confined spaces, they are alone and separate from the troubles of the world. Visconti contrasts these with the open battlefields, of a free Italy crying out for liberty with only the sky hanging over their heads. Likewise, in the early scenes, when Franz is courting Livia, the bridges and back alleys of Venice almost seem like something out of a fairy tale (not unlike the use of the city in Visconti's wonderful romantic 1957 film Le notti bianche); as things unravel, the city looks ashen and burdened by darkness. Design and color matter in Visconti's cinema; how everything looks is of equal importance to what is happening. Image is feeling, and there is a whole of feeling going on.

Criterion's much-anticipated Blu-Ray release of Seno presents a hi-def full frame version of the restored Film Foundation/Cineteca di Bologna copy of the 1954 film. The image quality is phenomenal, with rich, sumptuous Technicolor and a clean surface image. Detail is excellently tuned, and there is an overall warm, painterly glow to the look of the film. This is a movie that can be stared at without any concern for story or dialogue, its photography is an art object unto itself, and this digital release makes sure we get a glimpse of as much of each and every frame as possible. Keep an eye on background details, particularly in the last act of the film when Livia is back in Venice. Note how the walls and the objects on them appear. Compare the interior of Franz's hideout and all the decorations and the softer, though dilapidated textures, next to the altogether stark, pockmarked exterior wall that Livia walks along in despair--the level of texture in both is fantastic, though vastly different.

Criterion has also included the alternate English-language version--with its more suggestive title The Wanton Countess--and though its picture is surprisingly good considering what a little-seen artifact it is, you can see a big difference between it and the more comprehensive clean-up on its main counterpart. Presented in its entirety (though a good half hour shorter than the Italian version) and in full high-definition, it is interesting to peek in on, but not essential viewing. The big sell on this version is the actors are not dubbed over in Italian and you get a more accurate representation of what is presumed to be the contributions of Williams and Bowles.

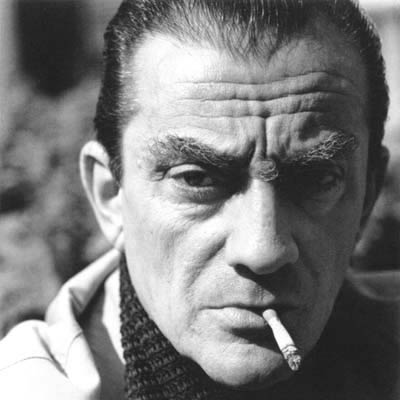

Luchino Visconti

Once it's all put together, the Senso - Criterion Collection Blu-Ray is another outstanding release in the company's ever expanding film library. The 1954 film from Luchino Visconti is a visually exciting melodrama of love and compromise. Set in the mid-1800s in Italy, it stars Farley Granger and Alida Valli as a soldier and a society woman from different sides of the same war who find love where they shouldn't and ultimately pay the price. With its full-bore picture restoration and packing the disc full of substantial bonus features, this release of Senso is high-brow home viewing at its finest.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Labels:

blu-ray,

scorsese,

tennessee williams,

visconti

Monday, February 21, 2011

BASIL DEARDEN'S LONDON UNDERGROUND - ECLIPSE SERIES 25

Basil Dearden is a name that is new to me, and so once again, Criterion's Eclipse Series has created a primer on a lesser-known filmmaker, putting together an intriguing boxed set that should provide an entertaining cinematic expedition for adventurous viewers. The 25th box in the collection, Basil Dearden's London Underground brings together four of the director's movies, made between 1959 and 1962, after the filmmaker had left Ealing Studios and struck out on his own. The movies here show the same mannerisms and penchant for light entertainment as was that studio's trademark, but Dearden's work nearly subverts the tradition with a progressive social conscience. In a way, Basil Dearden's London Underground shows us the bridge between post-War complacency and the cultural explosion of the 1960s. There are touches of the Kitchen Sink movement, though Dearden's aesthetic isn't as starkly realistic; rather, he practically creates his own reality, melding the familiar world of moviehouses with a point of view uniquely his own.

The box leads with Sapphire (92 minutes), a 1959 crime drama written by Janet Green. The film opens on a grisly scene: a dead girl being discovered in a pile of leaves in a public park. The color film stock of the late 1950s gives Sapphire a look that is more pastel than painterly, adding a surreal glimmer to the scene, as if Dearden wanted to undercut the murder's harsh effects by making it easy on the eyes.

The dead girl is Sapphire, and the mystery of who she is ends up being just as important as the circumstances surrounding her death. Sapphire is structured to lead viewers from the discovery of the body through all the steps the police take to solving her case. It's so straightforward, it struck me as having more in common with television police dramas of the period than with big-screen crime pictures. Superintendent Robert Hazard (Nigel Patrick) and Inspector Phil Learoyd (Michael Craig) could have easily been spun off into a Dragnet: London series.

While the one-two-three of the plot is not all that innovative, Sapphire is notable for the nature of the crime. As the girl's background is uncovered, racial tensions in English neighborhoods are also exposed. Dearden follows the investigation through all levels of social life, be it the whites-only college hang-outs or buttoned up middle-class homes, or the out-of-the-way black nightclubs and the more posh "international club" where immigrants of all stripes congregate. Though the storytelling can be stiff and the morality a bit obvious for modern sensibilities, when Sapphire is placed in its proper context, Dearden and Green should be seen as daring commentators who took a risk by being up front about the sticky hypocrisies and hidden animosity that polite society often covered up. Watching Sapphire, I often had the feeling that I was being led down back alleys I would not otherwise have seen. If the film itself falls short as entertainment, it's still utterly fascinating as a piece of art that tried to approach the times head on.

The second film in the set, The League of Gentlemen (116 mins.), falls back on more conventional genre trappings--it is a heist picture--and so it has aged and works better as cinema than Sapphire. It is no less of its time, however, as its band of crooks are British veterans who are bored with life after wartime and feeling disenfranchised. They "did their bit," as they say, but life has been no picnic in the intervening decades. Interestingly, they aren't noble soldiers fallen on hard times, they all have checkered backgrounds. Dearden doesn't avoid pat stereotypes about the Greatest Generation so much as he dances around them.

Colonel Hyde, played with acidic stoicism by Jack Hawkins, gathers together a group of ex-officers whom he knows to have had questionable careers and cajoles them into a cracking caper. His theory, which he bases off a dime novel called The Golden Fleece, is that if a group of military brass approaches a bank robbery with the same discipline as they would approach a battle, then there will be no stopping them. His group is a ragtag collection of personalities, including an old con man who poses as a priest (Roger Livesey) and a gentleman gambler (Nigel Patrick again). The film chronicles their preparation, including robbing an army base for weapons and supplies. (Another sign of the times: they affect Irish accents so the blame will be put on the IRA.) Once things are together, we then see Hyde's incredible plan.

The theft is excellently staged, like a British Ocean's 11

The 1961 film that followed League of Gentleman is more grounded in its drama and has more in common with Sapphire, including screenwriter Janet Green. Victim (100 mins.) stars Dirk Bogarde (The Night Porter) as Melvin Farr, a well-known barrister whose secret life nearly goes public when a boy (Peter McEnery) he shared a brief relationship with is caught in a blackmail racket due to an incriminating photo of the two of them. When the boy is pinched for stealing money to pay the extortion, he ends up killing himself. Overcome with guilt and a sense of duty, Farr decides to investigate the crime and put an end to this victimization of homosexuals.

At the time of the movie, being gay was a crime in England, and as Victim points out, the law against homosexuality ended up doing more harm to one class of people than it helped any others. The legal stigma left gay men open to this kind of attack. Crooks could take advantage of their desire not to be exposed. Surprisingly, Victim doesn't tiptoe around the issue or couch it in euphemism. Though it begins as a thriller with a central mystery--we aren't sure why the boy is in trouble or what he's intending to do--once the secret is uncovered, there is no pretending otherwise. Victim depicts gays secretly congregating in bars and even questions how someone like Farr ended up married and passing as straight. The ring of blackmailees spans all manner of society, be it blue collar workers like the dead boy, car salesmen, or famous actors. There is some tendency for proselytizing here--the policemen in particular are saddled with especially clumsy exposition, just as they were in Sapphire (perhaps it's Green, though she co-wrote Victim with John McCormick)--but the movie otherwise deals with the material in a way that maintains the integrity of the story.

Dirk Bogarde is extremely good in what was likely a risky role. Even these days an actor who plays gay, whether he is gay or not, often ends up perceived as such. Bogard handles Farr's sadness and disappointment in himself quite well, showing how brittle the man's situation has become. It's a difficult state of affairs: he might finally be able to be himself, but the cost will be high. The film had its own share of troubles. It was given an "X" rating in England, and U.S. censors tried to have the word "homosexual" removed, severely limiting the film's options for where it could be seen and by whom when Dearden and his producing partner refused.

Though the title of the box is Dearden's London Underground, one interesting thing about Victim is how much the gay lifestyle is seen as aboveground. Dearden doesn't take us into seedy bars hidden away, but instead shows his characters in neighborhood pubs where everyone knows who they are but turn a blind eye. This adds to the effectiveness of the political message: gay men are among us, they are getting along fine, so why subject them to these unfair practices. It's an intelligent use of storytelling as allegory that works with the images and the scenario rather than relying on preaching or other heavy explanations. The system is seen working against itself, and that is illustration enough.

Dearden's jazz world retake of Othello, the 1962 drama All Night Long (91 mins.), hearkens back to Sapphire in terms of its portrayal of interracial romance, but this time around, the union between black and white is not looked at as something scandalous. On the contrary, within the multiracial world of music, it's just a fact of life.

Paul Harris and Marti Stevens play bandleader Aurelius Rex and chanteuse Delia Lane, a jazz power couple who are celebrating their first anniversary in an out-of-the-way nightspot. The story transpires over a single all-night jam session, including real-life legends Dave Brubeck and Charles Mingus. Set to a constant soundtrack of incredible music, All Night Long's rhythm is set, like all music, by the drummer. Patrick McGoohan (The Prisoner

Basil Dearden, staging a script by Nel King and Peter Achilles, comes alive in this restricted setting, using the upstairs and downstairs and the side rooms of the club to create a physical puzzle box where he can move the different pieces of the narrative around. McGoohan is also amazing as the craven Johnny Cousin, oozing slime from every pore while playing his cohorts against one another. A lot of the other acting is a little stiff, though Richard Attenborough, who was also in League of Gentlemen, stands out as the owner of the club.

For many, the star of the film will be the music. Led by composer Philip Green, the revolving group of musicians, which also includes Johnny Dankworth and Tubby Hayes, is infections and keeps the movie bopping along, aiding its otherwise slim plot. Dearden shoots much of the jazz up close, and he lets the music affect the mood and, in a Shakespearian flourish, even the weather outside the club walls. It's fun stuff, and it closes out London Underground on an upswing.

Basil Dearden's London Underground is another great surprise from Criterion's Eclipse series. Staying true to its mission statement of bringing lesser-known material to movie fans in an affordable package, their newly released quartet of early '60s British movies sheds light on a progressive filmmaker tackling challenging subjects in ways that are surprising both for their innovation and Dearden's ability to work controversial material into traditional genre forms. A murder mystery, a bank heist, a blackmail sting, and an extended jazz party end up setting the stage for examinations of race, sexuality, and individual purpose. These aren't perfect films, but they are, for the most part, perfectly entertaining, and they make me eager to find more of Dearden's films and see what else this versatile filmmaker got up to, both prior to 1959 and after.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Thursday, February 17, 2011

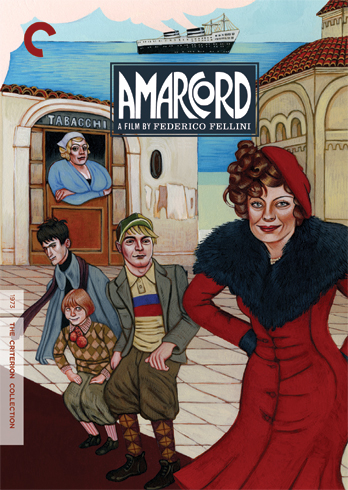

AMARCORD (Blu-Ray) - #4

Amarcord is the memoir of a prankster.

Federico Fellini's 1973 masterpiece, the title of which translates as "I Remember," is a playful collection of memories. It runs through both the filmmaker's personal history and also his films, creating echoes of his previous work as he exposes what may be the true inspirational origins for some of his more famous characters and scenes. In the crazed nymphomaniac Volpina, for instance, we see another version of the woman who was also Seraghina in 8 1/2 [review]. The childhood chums on the verge of manhood will eventually step out of this movie and star in I Vitelloni.

The maestro constructs Amarcord as a sort of greatest hits of one year in the life of the seaside village where he grew up, set in the early days of fascism and the reign of Mussolini. Beginning with the arrival of the "puffballs," airborne spores that signal the beginning of spring, he takes us through the seasons, from the leisure of summer to the foggy confusion of autumn and the wondrous cold of winter. It ends with the puffballs returning, a natural bookending. There are many continued rhymes through Amarcord, repetitions and reappearances, riding through the film's loose narrative like the man on the motorcycle who consistently arrives to split the town's activity right down the middle. There is also a sort of circle of life represented: we begin with the birth of spring and work our way to cold death. The spring festival that kicks off the movie, burning a witch in effigy, foreshadows a real death in the penultimate act of the film, but also the wedding that closes it. In surrendering the town's most desired romantic figure to married life, everyone is acknowledging that one phase of their existence is gone for good. Yet, marriage is for making babies, and so the cycle will begin anew.

There is a huge cast of characters running through Amarcord, but the Biondi family could be considered the focal point of most of the story. Titta Biondi (Bruno Zanin) is possibly Fellini himself. He dreams of sex and cinema, fantasizing about doing things that will bring him renown, like being a famous race car driver. He's still pretty immature--his mother won't buy him long pants, and his striped sweater and rainbow hat make him look like he has stepped out of an old newspaper comic strip--and his hormones are out of control, meaning sex trumps cinema any day of the week. It's fitting, though, that he makes his move on the gorgeous hairdresser Gradisca (Magali Noël) in a movie theatre while she watches her dream man, Gary Cooper. "Gradisca" means "whatever you desire," and while that isn't really the mantra of Amarcord, it is a theme just under the surface. Passions run hot in this town, and though much of that fire is devoted to boobs and butts, there is much to suggest that "getting out" is going to be the only goal that matters. Gradisca will be departing now that she has finally found the romance she has been searching for. The two biggest events that happen to the village are also all about passing through on the way to somewhere else: the Mille Miglia car race that winds its course through their streets, and the arrival of the Rex, a gargantuan cruise liner that the locals sail over the waves just to see float by.

Fellini takes us all through life in this town. We go to school and work, home and church. We watch people cruise the streets at night, and visit the local hotel resort to dance and sunbathe. We even see their politics, as many get uniformed up for a rally honoring Il Duce. In one of Amarcord's most surreal and comical moments, a giant Mussolini head that's been constructed out of flowers begins talking, granting the horny boy Ciccio (Fernando De Felice) his fondest wish: marriage to the dark beauty Aldina (Donatella Gambini). This is followed by the film's blackest moment, Titta's father (Armando Brancia) is taken from the house in the middle of the night to be questioned by the fascists. Someone has ratted the old man out for having contrary political beliefs. The pomp and circumstance and small-town go-along mentality is quickly busted by the thuggish behavior of their chosen leaders.

Amarcord is structured as a series of short scenes, strung together as nostalgic reverie. It's a shared experience, and there are multiple narrators. Though the lawyer (Luigi Rossi) gets the most lines, any townsperson can turn to the camera and start talking. A community like this really forms a single history, one that can only be chronicled in widescreen. Fellini and his cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno use the full length of the frame, creating colorful and complicated set-ups. Amarcord is a masterfully orchestrated melding of dreamscape and reality. It is truth filtered through the prism of recollection, grandly staged like Golden Age cinema, but with the flourish of classical painting. There is also an element of poetry to this. The references to Dante and Leopardi aren't for nothing, each sequence could be the stanza of an epic poem or the movements of a symphony (here, of course, orchestrated by the genius Nino Rota). Watch, too, how Fellini moves from one segment to the next, using heavy fades to go to black before coming back up on the next scene. It's like blinking. Close your eyes, and when you open them, new magic appears.

To try to divine the reality from the fiction in Amarcord would be a pointless effort. Fellini himself has denied its autobiographical nature, but not without a wink to say, "Well, resemblance to actual events may be more than coincidental." This is the ultimate prank of the movie, to bury the actual in spectacle, and to lend authenticity to what is clearly false. All art is reconstruction, all cinema is simulacrum, and Amarcord is its own cake, feeding on itself by being neither and both all on one plate.

This new Blu-Ray is the third version of Amarcord from Criterion, though it closely mirrors the previous DVD reissue

This disc was provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.

Tuesday, February 15, 2011

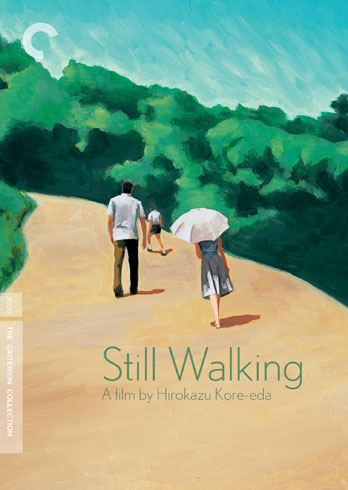

STILL WALKING (Blu-Ray) - #554

"We're only human."

Is there any better signal that someone has reached the end of their emotional rope than their having to evoke their own humanity? Second-eldest son Ryota Yokoyama, played with brittle stoicism by Hiroshi Abe (Survive Style +5 ), pulls out this cliché midway through Still Walking. The movie, written and directed by Hirokazu Kore-eda (Nobody Knows

), pulls out this cliché midway through Still Walking. The movie, written and directed by Hirokazu Kore-eda (Nobody Knows ), is a day-in-the-life of one family. They have gotten together--parents, brother, and sister, and their spouses and children--to commemorate the passing of Ryota's older brother Junpei some fifteen years earlier. As the movie progresses, one gets the sense that this isn't the only day of the year when Junpei's ghost is in the room. In death, the lost son can do no wrong, something that makes it tough for the siblings, who are forced to live out their lives complete with their mistakes and failures.

), is a day-in-the-life of one family. They have gotten together--parents, brother, and sister, and their spouses and children--to commemorate the passing of Ryota's older brother Junpei some fifteen years earlier. As the movie progresses, one gets the sense that this isn't the only day of the year when Junpei's ghost is in the room. In death, the lost son can do no wrong, something that makes it tough for the siblings, who are forced to live out their lives complete with their mistakes and failures.

Still Walking is a family drama. It examines the exclusive, shared world that can only be created through blood ties. In the Yokoyama clan, father (Yoshio Harada) is a retired doctor, set in his ways and grumpy about those ways. He wanted his boys to take over the family business, but one died and the other restores paintings for a meager living--and is in the process of failing. It's one of the many criss-crossing lines that the characters fail to see. They are too close to one another to realize the gap in their years doesn't mean they don't share common woes. Both the father and son fear their own obsolescence. The old man, Kyohei, no longer sees patients, and Ryota's occupation is becoming increasingly marginalized. Both need the validation of their work, yet neither is willing to acknowledge that need in the other.

Arguably, this is the central frustration that exists in all families: the need for one another vs. the way we tear each other down. Kore-eda expertly portrays the dual edge of this kind of shared experience. Still Walking is full of wonderful moments where ritual and memory come into play. There is an ease in which the relatives fall into their old ways. The smell of their mother's corn tempura reminds them all of years of sharing the same meal. Some remembrances tied to this food are exactly the same, some vary in detail from person to person. The differences are small, but they matter. Something Ryota said being refurbished to demonstrate how funny Junpei was creates a deep cut. At one point, the sister, Chinami (You), breaks down because of a petty comment from her father. He slights his wife (Kirin Kiki), insisting it's his hard work that built their home, though it's clear without anyone pointing it out that her constant toil is what has kept it together. (Don't you worry, she gets her own back later. Boy, can these two old folks bicker!)

As with any story about a group of "veterans" who have been together for years, a new sounding board for old grievances can be introduced into the narrative via rookies. Still Walking does this through Ryota's new wife, Yukari (Yio Natsukawa), and her son Atsushi (Shohei Tanaka). Yukari is a widow, so this is her second marriage, and the rest of the family whispers over Ryota's choice. Is a widow really the best spouse for someone who has never been married before? Ironically, it seems that their fear is that the dead husband will always be around and that Ryota can never get comfortable in his marriage bed. It's another crossover the Yokoyamas don't get at first, not until the subject of Junpei's widow comes up. It's a sad moment, and though we wish that the characters would stand up for themselves and each other with more force, the reason Still Walking is so good is because Kore-eda isn't afraid to let the film be achingly human. Later, when Yukari expresses how she feels like an outsider, Ryota shows little empathy, instead defaulting to defend his family. It kind of makes you want to smack the guy, especially as he got so upset when the family was viciously making fun of a practical stranger, the boy whom Junpei rescued from drowning, leading to his own death. It's a terrible error, but an all too obvious foible: he sees the boy's faults as his own.

In truth, this is the way people are. They do stupid things. Things that make us want to reach out and grab them and shake them and make them see their own error. The way we might with our own brother or father or mother. Kore-eda, for all intents and purposes, has made us one of the Yokoyamas. We care about them enough to be frustrated by them and to want them to do better.

Still Walking isn't very complicated in terms of presentation. It's a film where everything is under the surface. One has to watch and listen and experience what is being said and done and let it sink in to fully grasp all that is buried just below what's visible. Not much happens in the movie--most of it is the family sitting and eating, eating, eating--but so much happens that it's impossible to get it out of your head. Ozu is always the easy comparison when dealing with a film like this, but it's because he was so good at presenting common drama in an unfussy manner, there really is no improving on his standard. Ozu regularly took us into homes in much the same way Kore-eda does here, but the elder director kept us at a respectable middle-distance. Hirokazu Kore-eda and cinematographer Yutaka Yamazaki use the Yokoyama home as their primary set, letting the walls create a cramped intimacy. The relatives are often on top of one another, and so the camera is also on top of them. Tight framing allows for tiny conspiracies. Mother and daughter might share a bit of gossip while their father is just out of frame, or a little boy tries to hide his laughter by ducking below the common eyeline. Frills are kept to a minimum. When outside, Yamazaki gives us wide shots to show us how the world is vastly larger than the Yokoyama dinner table might make it seem, yet he doesn't go sweeping out across the rooftops. The actors stay in the image. For as much as life extends beyond them, they are an inextricable part of it.

Still Walking has a bittersweet ending, expertly seasoned to taste just right. Some progress is made in the farewell, enough to make everyone feel good about themselves, but then private thoughts show how far off they still are. Life is often a series of compromises and conciliations, massaging the situation just enough so that we can walk away with our dignity. It's there in the title, itself a reference to a pop song the mother plays in the movie. The romantic ballad at once wrestles with past heartbreak and pushes for new hope. Kore-eda uses it as a centerpiece to his film, like a mini narrative within the narrative, almost like instructions to his characters for how to cope, a signal that they are not alone in their desires and fears. Once this is done, they can get on with their story, which will then serve as instruction to the rest of us.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Is there any better signal that someone has reached the end of their emotional rope than their having to evoke their own humanity? Second-eldest son Ryota Yokoyama, played with brittle stoicism by Hiroshi Abe (Survive Style +5

Still Walking is a family drama. It examines the exclusive, shared world that can only be created through blood ties. In the Yokoyama clan, father (Yoshio Harada) is a retired doctor, set in his ways and grumpy about those ways. He wanted his boys to take over the family business, but one died and the other restores paintings for a meager living--and is in the process of failing. It's one of the many criss-crossing lines that the characters fail to see. They are too close to one another to realize the gap in their years doesn't mean they don't share common woes. Both the father and son fear their own obsolescence. The old man, Kyohei, no longer sees patients, and Ryota's occupation is becoming increasingly marginalized. Both need the validation of their work, yet neither is willing to acknowledge that need in the other.

Arguably, this is the central frustration that exists in all families: the need for one another vs. the way we tear each other down. Kore-eda expertly portrays the dual edge of this kind of shared experience. Still Walking is full of wonderful moments where ritual and memory come into play. There is an ease in which the relatives fall into their old ways. The smell of their mother's corn tempura reminds them all of years of sharing the same meal. Some remembrances tied to this food are exactly the same, some vary in detail from person to person. The differences are small, but they matter. Something Ryota said being refurbished to demonstrate how funny Junpei was creates a deep cut. At one point, the sister, Chinami (You), breaks down because of a petty comment from her father. He slights his wife (Kirin Kiki), insisting it's his hard work that built their home, though it's clear without anyone pointing it out that her constant toil is what has kept it together. (Don't you worry, she gets her own back later. Boy, can these two old folks bicker!)

As with any story about a group of "veterans" who have been together for years, a new sounding board for old grievances can be introduced into the narrative via rookies. Still Walking does this through Ryota's new wife, Yukari (Yio Natsukawa), and her son Atsushi (Shohei Tanaka). Yukari is a widow, so this is her second marriage, and the rest of the family whispers over Ryota's choice. Is a widow really the best spouse for someone who has never been married before? Ironically, it seems that their fear is that the dead husband will always be around and that Ryota can never get comfortable in his marriage bed. It's another crossover the Yokoyamas don't get at first, not until the subject of Junpei's widow comes up. It's a sad moment, and though we wish that the characters would stand up for themselves and each other with more force, the reason Still Walking is so good is because Kore-eda isn't afraid to let the film be achingly human. Later, when Yukari expresses how she feels like an outsider, Ryota shows little empathy, instead defaulting to defend his family. It kind of makes you want to smack the guy, especially as he got so upset when the family was viciously making fun of a practical stranger, the boy whom Junpei rescued from drowning, leading to his own death. It's a terrible error, but an all too obvious foible: he sees the boy's faults as his own.

In truth, this is the way people are. They do stupid things. Things that make us want to reach out and grab them and shake them and make them see their own error. The way we might with our own brother or father or mother. Kore-eda, for all intents and purposes, has made us one of the Yokoyamas. We care about them enough to be frustrated by them and to want them to do better.

Still Walking isn't very complicated in terms of presentation. It's a film where everything is under the surface. One has to watch and listen and experience what is being said and done and let it sink in to fully grasp all that is buried just below what's visible. Not much happens in the movie--most of it is the family sitting and eating, eating, eating--but so much happens that it's impossible to get it out of your head. Ozu is always the easy comparison when dealing with a film like this, but it's because he was so good at presenting common drama in an unfussy manner, there really is no improving on his standard. Ozu regularly took us into homes in much the same way Kore-eda does here, but the elder director kept us at a respectable middle-distance. Hirokazu Kore-eda and cinematographer Yutaka Yamazaki use the Yokoyama home as their primary set, letting the walls create a cramped intimacy. The relatives are often on top of one another, and so the camera is also on top of them. Tight framing allows for tiny conspiracies. Mother and daughter might share a bit of gossip while their father is just out of frame, or a little boy tries to hide his laughter by ducking below the common eyeline. Frills are kept to a minimum. When outside, Yamazaki gives us wide shots to show us how the world is vastly larger than the Yokoyama dinner table might make it seem, yet he doesn't go sweeping out across the rooftops. The actors stay in the image. For as much as life extends beyond them, they are an inextricable part of it.

Still Walking has a bittersweet ending, expertly seasoned to taste just right. Some progress is made in the farewell, enough to make everyone feel good about themselves, but then private thoughts show how far off they still are. Life is often a series of compromises and conciliations, massaging the situation just enough so that we can walk away with our dignity. It's there in the title, itself a reference to a pop song the mother plays in the movie. The romantic ballad at once wrestles with past heartbreak and pushes for new hope. Kore-eda uses it as a centerpiece to his film, like a mini narrative within the narrative, almost like instructions to his characters for how to cope, a signal that they are not alone in their desires and fears. Once this is done, they can get on with their story, which will then serve as instruction to the rest of us.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Wednesday, February 9, 2011

SIDELINE: PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL

The 34th Portland International Film Festival officially starts tomorrow, February 10, and runs through February 26. The full line-up of movies is fairly extensive, including multiple programs featuring short films.

This year, I am joining forces with two other press outlets to review some of the selections, which range from the new Abbas Kiarostami release to a flick about mutated Japanese school girls. I've been watching screenings pretty much every day for nearly two weeks now. I may go blind, but I am soldiering on.

You can read short reviews by me as part of the the Portland Mercury's festival coverage, online through the link but also in the paper. Not sure if all of the reviews will be in both. I think depending on the screening schedule, some will just be online. Several went up today: Incendies, The Human Resources Manager, and His & Hers.

I am also writing longer reviews for the guys over at Criterion Cast, the first of which also went live today. You can access them at the Cast's PIFF microsite, along with the rest of their coverage, or jump direct to my author's page.

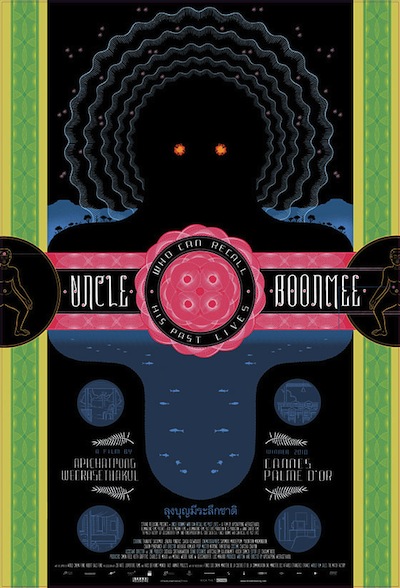

I'll be updating regularly over there for the next couple of weeks. Not sure how often the Merc will update their online list. I know I just sent them the blurb for Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, which I saw this morning. Speaking of, did you see this awesome poster Chris Ware designed for the theatrical release?

This year, I am joining forces with two other press outlets to review some of the selections, which range from the new Abbas Kiarostami release to a flick about mutated Japanese school girls. I've been watching screenings pretty much every day for nearly two weeks now. I may go blind, but I am soldiering on.

You can read short reviews by me as part of the the Portland Mercury's festival coverage, online through the link but also in the paper. Not sure if all of the reviews will be in both. I think depending on the screening schedule, some will just be online. Several went up today: Incendies, The Human Resources Manager, and His & Hers.

I am also writing longer reviews for the guys over at Criterion Cast, the first of which also went live today. You can access them at the Cast's PIFF microsite, along with the rest of their coverage, or jump direct to my author's page.

I'll be updating regularly over there for the next couple of weeks. Not sure how often the Merc will update their online list. I know I just sent them the blurb for Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, which I saw this morning. Speaking of, did you see this awesome poster Chris Ware designed for the theatrical release?

Wednesday, February 2, 2011

DOWNHILL RACER - #494

"How fast must a man go to get from where he's at...?"

There are two parts to Downhill Racer. There is the part that is the racing, and there is the part that is the waiting for the racing. There is no in between.

The waiting for the racing is strange, incomplete, and quiet. No one says much. They do things, but at the same time, none of it is important. When it starts to get important, it distracts from the racing.

The racing is also quiet, but it's a different kind of quiet. It's isolated. Solitary. The main sound the racer hears is his skis on snow. The audio design for the movie is pretty incredible. When the skis catch air, the silence that occurs is definite. There is no other ambient noise. It's like flipping a switch to mute, and then contact activates the speakers again.

Downhill Racer is a 1969 film directed by Michael Ritchie and written by James Salter. It stars Robert Redford as David Chappellet, a contender from Idaho Falls, Colorado, a small American town that is far away from the European racing circuit that David is joining. David is one of two new members of the U.S. team, replacing another athlete whose injuries from a crash have taken him out of competition. David is an unknown, seemingly older than the other boys, and not a part of their network. His coach, Claire (Gene Hackman), apparently knows something about Chappellet that they do not. The time on his first run gives them an indication of what that is. The dude is fast.

David is confident and cocky--they are not the same thing. His confidence means he has enough belief to perform well, but the cockiness means he has the added belief that he can do anything. It makes him restless and inconsistent on the slopes, and it's the kind of thing that transfers over to his real life. He drives fast, and he chases girls just as quickly. He doesn't say much, just what he has to. This rubs his teammates the wrong way, but if they saw David going back home to the farm where he grew up the way we do, they might understand. It's a kind of American stoicism. David's father (Walter Stroud) doesn't even stop to greet him when the boy comes home, and he's not all that impressed with his Olympic aspirations. It's the only time we see David rattled. His old man's nonchalance and measured judgment clearly irritates him.

Which may also explain the appeal of skiing for Dave. His closest competition on the squad, Creech (Jim McMullan), complains to the assistant coach (Dabney Coleman) that David doesn't care about the team, and the coach replies that it doesn't really matter, it's not really a team sport anyway. It's not clear why Creech doesn't get that, it's obvious to us and we aren't up there racing. Michael Ritchie makes sure we see the action as close as possible to how the racer's see it, shooting the runs mostly from the skier's point of view. Noticeably, the first race, when we're supposed to be observing David and not yet climbing in his boots, is shot exclusively from an outside vantage point. It's exhilarating and disorienting, the way the camera rockets down the mountain. It gives the audience a glimpse of the kind of tunnel vision that can occur when descending the mountain.

Presumably, this is the sensation David is chasing. Not just the thrill of adrenaline, but the self-sufficiency and isolation. No need for small talk, and no room for the disappointment of others. It's just you and the snow. Sure, you can crash, but if you're racing just for you, who cares how that effects others? Win or lose, the time is yours.

Downhill Racer is a strange film. It's certainly not like any other sports film I've ever seen. The plot tracks several seasons for the team, leading up to the Olympics, and though Ritchie depicts the jolt of the individual races, there is no real escalation from competition to competition. The opposite, in fact. The plot grows choppier and choppier, we move from peak to peak faster. If it weren't for a barely there subplot with a woman (Camilla Sparv) that David has an affair with, there would be no pause at all after that brief trip home. One can surmise that David is never going back to Colorado, so why spend any time away from the slopes.

The Olympics have their own tension. Ritchie creates an amped excitement in David's big run by ingeniously jumping from TV monitor to TV monitor in the pressroom as his time is counted off, one second per television. There is also another gut wrenching use of silence, as David and Claire watch to see if his closest competitor will manage to beat him. Even then, we aren't really rooting for David. The script has a third act hiccup, where his hubris causes damage, but outside of a nice scene-grabbing monologue that Salter writes for Gene Hackman, there's no push to make it seem like this is a mistake David must bounce back from. It's just another day out in the powder.

Released at the end of the 1960s, Downhill Racer is in every way a film of that era, and also points ahead to the maverick years coming in American cinema. Aesthetically, the movie is restrained, striving for realism and not reliant on traditional storytelling. Director of photography Brian Probyn (Badlands ) worked with eight cameramen to capture the skiing, and the multiple angles lends an authenticity to the action. There are no conventional cutaways or rear projection like we might have gotten even a decade earlier. It's something more akin to actual sports documentary. The only thing that rings false is Kenyon Hopkins' music. There's something off-key about it. The horns and mandolins and overall rhythm seem more suited to a '60s cop drama on television than a movie of this kind.

) worked with eight cameramen to capture the skiing, and the multiple angles lends an authenticity to the action. There are no conventional cutaways or rear projection like we might have gotten even a decade earlier. It's something more akin to actual sports documentary. The only thing that rings false is Kenyon Hopkins' music. There's something off-key about it. The horns and mandolins and overall rhythm seem more suited to a '60s cop drama on television than a movie of this kind.

Downhill Racer is also thematically in line with the dissatisfaction of 1969. This movie is about demystifying heroes. David Chappellet might ski with the letters U, S, and A printed on his helmet, but there is no patriotism to it. Indeed, the way Claire has to constantly hustle for money, it's not even like the home country is lending their skiers the full support of the national consciousness. David Chappellet is an anti-hero, a guy who only fights for himself. Ironically, I don't think anyone who wasn't as classically good looking as Robert Redford could have pulled it off. In the commentary on the recent release of Broadcast News [review], during the scene at the news director's party where William Hurt's character is seen struggling with eating a deviled egg, James L. Brooks says he believes that kind of dunderheaded gag is something that is only really funny with a handsome actor; if he was dumb and unattractive, it would veer toward being pathetic. Here, too, I think Chappellet needs a certain Hollywood charisma, the performer's inherent likability, to keep him from being just another asshole. Just like it takes a performer as down to earth as Hackman to play his foil. The same way Albert Brooks knows something is wrong with William Hurt in the Brooks movie, so too does Coach Claire know that Chappellet could blow it. In both cases, those guys also know what kind of success these flawed figures are likely to achieve.

In a lesser movie, David Chappellet would find redemption. In Downhill Racer, there is only disappointment ahead. I don't want to give away which way the movie turns, that's something for you to experience, but I will say, there is no denouement. The results come in, and that's that, and I think we are meant to be unsatisfied. How did this man get here, and how did he achieve what he achieved? Good or bad, was it right? I would posit that this is a question that the culture was asking at the time, and by this point in the social movement that defined the 1960s, the question was no longer being asked of the government in so much as the counter-culture and the activists and, really, just about every citizen with a conscience, was asking him or herself. Even fighting the power has its pitfalls. David's father says it outright when his son boasts that one day he'll be champion: "The world's full of 'em."

Downhill Racer trailer

There are two parts to Downhill Racer. There is the part that is the racing, and there is the part that is the waiting for the racing. There is no in between.

The waiting for the racing is strange, incomplete, and quiet. No one says much. They do things, but at the same time, none of it is important. When it starts to get important, it distracts from the racing.

The racing is also quiet, but it's a different kind of quiet. It's isolated. Solitary. The main sound the racer hears is his skis on snow. The audio design for the movie is pretty incredible. When the skis catch air, the silence that occurs is definite. There is no other ambient noise. It's like flipping a switch to mute, and then contact activates the speakers again.

Downhill Racer is a 1969 film directed by Michael Ritchie and written by James Salter. It stars Robert Redford as David Chappellet, a contender from Idaho Falls, Colorado, a small American town that is far away from the European racing circuit that David is joining. David is one of two new members of the U.S. team, replacing another athlete whose injuries from a crash have taken him out of competition. David is an unknown, seemingly older than the other boys, and not a part of their network. His coach, Claire (Gene Hackman), apparently knows something about Chappellet that they do not. The time on his first run gives them an indication of what that is. The dude is fast.

David is confident and cocky--they are not the same thing. His confidence means he has enough belief to perform well, but the cockiness means he has the added belief that he can do anything. It makes him restless and inconsistent on the slopes, and it's the kind of thing that transfers over to his real life. He drives fast, and he chases girls just as quickly. He doesn't say much, just what he has to. This rubs his teammates the wrong way, but if they saw David going back home to the farm where he grew up the way we do, they might understand. It's a kind of American stoicism. David's father (Walter Stroud) doesn't even stop to greet him when the boy comes home, and he's not all that impressed with his Olympic aspirations. It's the only time we see David rattled. His old man's nonchalance and measured judgment clearly irritates him.

Which may also explain the appeal of skiing for Dave. His closest competition on the squad, Creech (Jim McMullan), complains to the assistant coach (Dabney Coleman) that David doesn't care about the team, and the coach replies that it doesn't really matter, it's not really a team sport anyway. It's not clear why Creech doesn't get that, it's obvious to us and we aren't up there racing. Michael Ritchie makes sure we see the action as close as possible to how the racer's see it, shooting the runs mostly from the skier's point of view. Noticeably, the first race, when we're supposed to be observing David and not yet climbing in his boots, is shot exclusively from an outside vantage point. It's exhilarating and disorienting, the way the camera rockets down the mountain. It gives the audience a glimpse of the kind of tunnel vision that can occur when descending the mountain.

Presumably, this is the sensation David is chasing. Not just the thrill of adrenaline, but the self-sufficiency and isolation. No need for small talk, and no room for the disappointment of others. It's just you and the snow. Sure, you can crash, but if you're racing just for you, who cares how that effects others? Win or lose, the time is yours.

Downhill Racer is a strange film. It's certainly not like any other sports film I've ever seen. The plot tracks several seasons for the team, leading up to the Olympics, and though Ritchie depicts the jolt of the individual races, there is no real escalation from competition to competition. The opposite, in fact. The plot grows choppier and choppier, we move from peak to peak faster. If it weren't for a barely there subplot with a woman (Camilla Sparv) that David has an affair with, there would be no pause at all after that brief trip home. One can surmise that David is never going back to Colorado, so why spend any time away from the slopes.

The Olympics have their own tension. Ritchie creates an amped excitement in David's big run by ingeniously jumping from TV monitor to TV monitor in the pressroom as his time is counted off, one second per television. There is also another gut wrenching use of silence, as David and Claire watch to see if his closest competitor will manage to beat him. Even then, we aren't really rooting for David. The script has a third act hiccup, where his hubris causes damage, but outside of a nice scene-grabbing monologue that Salter writes for Gene Hackman, there's no push to make it seem like this is a mistake David must bounce back from. It's just another day out in the powder.

Released at the end of the 1960s, Downhill Racer is in every way a film of that era, and also points ahead to the maverick years coming in American cinema. Aesthetically, the movie is restrained, striving for realism and not reliant on traditional storytelling. Director of photography Brian Probyn (Badlands

Downhill Racer is also thematically in line with the dissatisfaction of 1969. This movie is about demystifying heroes. David Chappellet might ski with the letters U, S, and A printed on his helmet, but there is no patriotism to it. Indeed, the way Claire has to constantly hustle for money, it's not even like the home country is lending their skiers the full support of the national consciousness. David Chappellet is an anti-hero, a guy who only fights for himself. Ironically, I don't think anyone who wasn't as classically good looking as Robert Redford could have pulled it off. In the commentary on the recent release of Broadcast News [review], during the scene at the news director's party where William Hurt's character is seen struggling with eating a deviled egg, James L. Brooks says he believes that kind of dunderheaded gag is something that is only really funny with a handsome actor; if he was dumb and unattractive, it would veer toward being pathetic. Here, too, I think Chappellet needs a certain Hollywood charisma, the performer's inherent likability, to keep him from being just another asshole. Just like it takes a performer as down to earth as Hackman to play his foil. The same way Albert Brooks knows something is wrong with William Hurt in the Brooks movie, so too does Coach Claire know that Chappellet could blow it. In both cases, those guys also know what kind of success these flawed figures are likely to achieve.

In a lesser movie, David Chappellet would find redemption. In Downhill Racer, there is only disappointment ahead. I don't want to give away which way the movie turns, that's something for you to experience, but I will say, there is no denouement. The results come in, and that's that, and I think we are meant to be unsatisfied. How did this man get here, and how did he achieve what he achieved? Good or bad, was it right? I would posit that this is a question that the culture was asking at the time, and by this point in the social movement that defined the 1960s, the question was no longer being asked of the government in so much as the counter-culture and the activists and, really, just about every citizen with a conscience, was asking him or herself. Even fighting the power has its pitfalls. David's father says it outright when his son boasts that one day he'll be champion: "The world's full of 'em."

Downhill Racer trailer

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)