Other movies I reviewed over the last month...

IN THEATRES...

* All Good Things, a true-ish crime story that is fine despite its distanced point of view.

* Another Year, Mike Leigh's incisive take on the ups and downs of a year in the life of a particular group of friends.

* Biutiful, Javier Bardem is here to help, but Alejandro González Iñárritu's movie is still absolutely dreadful.

* The Green Hornet, the odd pairing of Michel Gondry and Seth Rogen gives us too much and yet not enough.

* The Illusionist, Sylvain Chomet's charming, bittersweet animated adaptation of Jacques Tati.

* On the Bowery, Lionel Rogosin's 1957 Neorealist look at life on skid row.

ON DVD/BD...

* Backdraft, examining my past enjoyment of Ron Howard movies by watching the BD of the movie that started it all going wrong.

* The Color Purple, Steven Spielberg's unlikely adaptation of Alice Walker is still surprisingly effective.

* Inspector Bellamy, the final film from Claude Chabrol feels strangely unfinished. Starring Gerard Depardieu.

* Last Train Home, a heartbreaking documentary about a family of migrant workers in China.

* Red Hill, a modern western from Australia, starring the guy who plays Jason Stackhouse on True Blood as a city sheriff stuck in a small-town revenge plot.

Speaking of True Blood...

* The Romantics, Anna Paquin shines next to a bunch of TV refugees doing their best with an underdeveloped script.

* Welcome to the Rileys, a middling indie drama given significant heft by accomplished performances from James Gandolfini and Melissa Leo. (Not so fast, Kristen Stewart...)

* A Woman, a Gun and a Noodle Shop, Zhang Yimou's remake of Blood Simple is now on DVD.

Monday, January 31, 2011

Friday, January 28, 2011

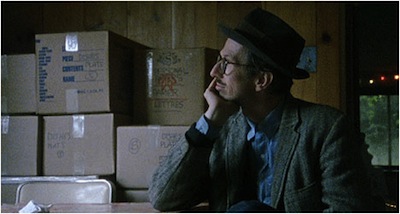

BROADCAST NEWS (Blu-Ray) - #552

"It must be nice to always believe you know better, to always think you're the smartest person in the room."

"No. It's awful."

Man, I know I liked Broadcast News when I saw it at age 15, because the exchange between the unstoppable news producer Jane Craig and her boss quoted above has always stuck with me, but thinking about it now, I know I didn't really get it. In fact, even that, my favorite quote, is one I totally misremembered. In my brain, Jane nods, agrees with her boss, and silently says, "Damn straight it's nice." It's how I reacted when my father told me similar things many times in my late teens. Here I was basing my whole philosophy on a quote I didn't have right from a movie possessing complexities far beyond me. I did have a crush on Holly Hunter, who played Jane, I know that--but geez, that just seems trivial.

Broadcast News was released in 1987, four years after writer/director James L. Brooks had transitioned from the little screen to the big one with his cinema debut, Terms of Endearment . Holly Hunter was a virtual unknown at the time, though she was having a hell of a year. 1987 was also when Raising Arizona

. Holly Hunter was a virtual unknown at the time, though she was having a hell of a year. 1987 was also when Raising Arizona was released, though I don't think to quite the same acclaim as Broadcast News. CNN and 24-hour cable news was still in its infancy at the time, and network TV still ruled--so much so that Brooks doesn't even mention that there is any alternative, despite the subtext of his romantic comedy being the changing face of television journalism.

was released, though I don't think to quite the same acclaim as Broadcast News. CNN and 24-hour cable news was still in its infancy at the time, and network TV still ruled--so much so that Brooks doesn't even mention that there is any alternative, despite the subtext of his romantic comedy being the changing face of television journalism.

The literal changing face is played by William Hurt. His character is Tom Grunick, a sports reporter upgraded to neophyte newsman at the Washington bureau where Jane is a segment producer. She regularly works with Aaron Altman (Albert Brooks), a fiercely intelligent reporter who isn't afraid to dig deep into the story. They have a special rapport and shared ideals: the integrity of the news is sacrosanct, never to be breached. Empty personalities reading off a teleprompter should not be valued over smart journalists who write their own copy, and fluff pieces that make people happy shouldn't come at the expense of telling the audience what's really happening in the world. The chemistry between Jane and Aaron is obvious, but naturally, like the audience and the network executives, Jane is more drawn to Tom's pretty face. She begins guiding him through his early work, culminating in an unplanned Sunday anchor slot when Libya attacks a U.S. base in Sicily. It's a marvelous scene, moving back and forth between the news desk and the control room, with Jane whispering facts--some supplied by Aaron via telephone--into Tom's ear, directing him where he should go.

The exhilaration the pair feel following the live high-wire act pretty much seals the deal between them. It's a euphoria comparable to sex, which Tom says outright. Jane was in his head, lighting up his intellectual pleasure centers, reversing traditional gender roles, filling him with everything she had to give. It was, quite literally, a mindfuck. The only problem is that Jane essentially sees Tom as brainless, and there are questions of how much she respects the eager go-getter. When Aaron admits his own feelings, both the love he has for her and his disdain for his rival, it poses quite a puzzle, one Jane has a hard time solving.

It's a traditional romantic comedy formula, and make no mistake, Broadcast News is a romantic comedy. It's one of the first things that struck me about the movie seeing it again after all these years. We're not very far into the narrative when Jane and her crew, under tremendous deadline pressure, push a story up to its very last minute, forcing Joan Cusack, playing one of Jane's support staff, to run from the editing bay to the broadcast room, dodging filing cabinets and jumping over babies. It's expertly choreographed slapstick. Broadcast News is off and running.

One could say this is James L. Brooks' true gift: balancing a very traditional sense of comedy with incisive commentary on human emotion. The first three scenes of Broadcast News are introductions to the three principle characters as schoolkids. It's sort of a hokey, Rob Reiner-ish device, exaggerating their foibles for quick guffaws--or so it seems. At different times later in the movie, all three of those scenes will be replayed. No commentary is offered, and the repetition isn't exact, but we see the behavior again--Tom's self-chastising and determination, Aaron's superiority and pushing too hard to get the last word, Jane's jumpiness and compulsions. These are people who let themselves be defined by their faults because they mistake them for virtue.

The romantic set-up is quite meaningful. Whom Jane chooses is akin to the direction television journalism will also take. Do we stick with safe, nice, and easy to look at, or do we go with unvarnished and true? In a lesser romantic comedy, the choice would be obvious, but Brooks isn't going to let his characters off the hook that easily. If this were Pretty in Pink [review], sure, we'd all be rooting for Ducky, but Broadcast News is set in an adult world where the bloom of romance has drooped a little. (And that's not a knock at Pretty in Pink, bless its teenaged soul.) Brooks is in choppy waters. Reconciling the heart and the head requires compromise, but all points on this love triangle are too rigid when it comes to their own particular angles. They are too strident in their ideals to change course for anyone else.

Surprisingly, it's Tom that gets closest to making room for someone else. I definitely wouldn't have known that as a younger moviegoer. He'd have been the villain, no question. Now, not so much. In fact, Jane and Aaron are both the kind of nerds that grow up to be bullies. Off the playground, when it's no longer viable to beat your opponent to a pulp with your fists, the nerds get their revenge by doing it with their brains. Tom is the most genuine, he accepts his weaknesses and tries to build from there. William Hurt gets the well-intentioned lunkhead to a tee, giving him an insatiable yet befuddled curiosity, seemingly borrowing Tom's body language from dogs. Notice how he always cocks his head to listen. Every canine I've ever known has looked at me just that way.

When Tom eventually tries to put it all on the line for Jane, when she's ready to call it quits, he acknowledges that they disagree and asks for some leeway to work out their differences. Jane can't accept that. Everything for her has one right way: her way. Sometimes that means not having what she wants because she must instead pursue what is correct. It's what she means about it being awful to be right. Let's face it, the joy of life is often in the mistakes. (And, as an aside, anyone else think of the end of Michael Clayton [review] during that cab ride from the airport?)

Holly Hunter is phenomenal as Jane--despite being burdened with the not-so-good clothes and the sometimes iffy hair of the late 1980s. She gets in Jane's head and stays there, much like Jane herself. Yet, it's not just a cerebral performance, it's physical, too. Many of her reactions in the movie are priceless. Jane is a bundle of kinetic energy, always moving forward, always reacting. At times, people tell her news she's not ready to hear--such as, "I love you"--and she literally flinches, like the information is a blast of bad air. The only time she is truly at rest is when she is directing the news broadcast. The director's chair is the one physical space where her mind is allowed to move at its natural speed, when the energy and her thoughts are focused in the same place. She doesn't have to keep moving just to keep up with it.

I know I am being very enthusiastic here, and I don't mean to imply that Broadcast News is without its faults. In some ways, James L. Brooks' expert construction is too slick. The storytelling can be a little quaint and even convenient, much in the same way that Albert Brooks' well-timed zingers stand out from the reality of the movie as just being too perfect. Albert is good, but sometimes he appears to know he has a great one-liner. (Ironic how much Aaron Altman absolutely abhors alliteration given his name.) Those who find romantic comedies too predictable probably won't be all that surprised by how the plot twists here, either, not even when Brooks actually breaks from convention.

To that I say so what. Let Broadcast News be flawed, let it have its merry way with genre tropes. That's the compromise enjoying a love story sometimes requires. Let go of your modern conceits, and embrace what is maybe old fashioned about romantic movies. Give your head a rest and let your heart take hold of the remote. Because, damnit, Broadcast News is just so likable, getting mad that it works too well just seems disingenuous. Surrender to the moment, and leave the lonely taxi rides to someone else.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

"No. It's awful."

Man, I know I liked Broadcast News when I saw it at age 15, because the exchange between the unstoppable news producer Jane Craig and her boss quoted above has always stuck with me, but thinking about it now, I know I didn't really get it. In fact, even that, my favorite quote, is one I totally misremembered. In my brain, Jane nods, agrees with her boss, and silently says, "Damn straight it's nice." It's how I reacted when my father told me similar things many times in my late teens. Here I was basing my whole philosophy on a quote I didn't have right from a movie possessing complexities far beyond me. I did have a crush on Holly Hunter, who played Jane, I know that--but geez, that just seems trivial.

Broadcast News was released in 1987, four years after writer/director James L. Brooks had transitioned from the little screen to the big one with his cinema debut, Terms of Endearment

The literal changing face is played by William Hurt. His character is Tom Grunick, a sports reporter upgraded to neophyte newsman at the Washington bureau where Jane is a segment producer. She regularly works with Aaron Altman (Albert Brooks), a fiercely intelligent reporter who isn't afraid to dig deep into the story. They have a special rapport and shared ideals: the integrity of the news is sacrosanct, never to be breached. Empty personalities reading off a teleprompter should not be valued over smart journalists who write their own copy, and fluff pieces that make people happy shouldn't come at the expense of telling the audience what's really happening in the world. The chemistry between Jane and Aaron is obvious, but naturally, like the audience and the network executives, Jane is more drawn to Tom's pretty face. She begins guiding him through his early work, culminating in an unplanned Sunday anchor slot when Libya attacks a U.S. base in Sicily. It's a marvelous scene, moving back and forth between the news desk and the control room, with Jane whispering facts--some supplied by Aaron via telephone--into Tom's ear, directing him where he should go.

The exhilaration the pair feel following the live high-wire act pretty much seals the deal between them. It's a euphoria comparable to sex, which Tom says outright. Jane was in his head, lighting up his intellectual pleasure centers, reversing traditional gender roles, filling him with everything she had to give. It was, quite literally, a mindfuck. The only problem is that Jane essentially sees Tom as brainless, and there are questions of how much she respects the eager go-getter. When Aaron admits his own feelings, both the love he has for her and his disdain for his rival, it poses quite a puzzle, one Jane has a hard time solving.

It's a traditional romantic comedy formula, and make no mistake, Broadcast News is a romantic comedy. It's one of the first things that struck me about the movie seeing it again after all these years. We're not very far into the narrative when Jane and her crew, under tremendous deadline pressure, push a story up to its very last minute, forcing Joan Cusack, playing one of Jane's support staff, to run from the editing bay to the broadcast room, dodging filing cabinets and jumping over babies. It's expertly choreographed slapstick. Broadcast News is off and running.

One could say this is James L. Brooks' true gift: balancing a very traditional sense of comedy with incisive commentary on human emotion. The first three scenes of Broadcast News are introductions to the three principle characters as schoolkids. It's sort of a hokey, Rob Reiner-ish device, exaggerating their foibles for quick guffaws--or so it seems. At different times later in the movie, all three of those scenes will be replayed. No commentary is offered, and the repetition isn't exact, but we see the behavior again--Tom's self-chastising and determination, Aaron's superiority and pushing too hard to get the last word, Jane's jumpiness and compulsions. These are people who let themselves be defined by their faults because they mistake them for virtue.

The romantic set-up is quite meaningful. Whom Jane chooses is akin to the direction television journalism will also take. Do we stick with safe, nice, and easy to look at, or do we go with unvarnished and true? In a lesser romantic comedy, the choice would be obvious, but Brooks isn't going to let his characters off the hook that easily. If this were Pretty in Pink [review], sure, we'd all be rooting for Ducky, but Broadcast News is set in an adult world where the bloom of romance has drooped a little. (And that's not a knock at Pretty in Pink, bless its teenaged soul.) Brooks is in choppy waters. Reconciling the heart and the head requires compromise, but all points on this love triangle are too rigid when it comes to their own particular angles. They are too strident in their ideals to change course for anyone else.

Surprisingly, it's Tom that gets closest to making room for someone else. I definitely wouldn't have known that as a younger moviegoer. He'd have been the villain, no question. Now, not so much. In fact, Jane and Aaron are both the kind of nerds that grow up to be bullies. Off the playground, when it's no longer viable to beat your opponent to a pulp with your fists, the nerds get their revenge by doing it with their brains. Tom is the most genuine, he accepts his weaknesses and tries to build from there. William Hurt gets the well-intentioned lunkhead to a tee, giving him an insatiable yet befuddled curiosity, seemingly borrowing Tom's body language from dogs. Notice how he always cocks his head to listen. Every canine I've ever known has looked at me just that way.

When Tom eventually tries to put it all on the line for Jane, when she's ready to call it quits, he acknowledges that they disagree and asks for some leeway to work out their differences. Jane can't accept that. Everything for her has one right way: her way. Sometimes that means not having what she wants because she must instead pursue what is correct. It's what she means about it being awful to be right. Let's face it, the joy of life is often in the mistakes. (And, as an aside, anyone else think of the end of Michael Clayton [review] during that cab ride from the airport?)

Holly Hunter is phenomenal as Jane--despite being burdened with the not-so-good clothes and the sometimes iffy hair of the late 1980s. She gets in Jane's head and stays there, much like Jane herself. Yet, it's not just a cerebral performance, it's physical, too. Many of her reactions in the movie are priceless. Jane is a bundle of kinetic energy, always moving forward, always reacting. At times, people tell her news she's not ready to hear--such as, "I love you"--and she literally flinches, like the information is a blast of bad air. The only time she is truly at rest is when she is directing the news broadcast. The director's chair is the one physical space where her mind is allowed to move at its natural speed, when the energy and her thoughts are focused in the same place. She doesn't have to keep moving just to keep up with it.

I know I am being very enthusiastic here, and I don't mean to imply that Broadcast News is without its faults. In some ways, James L. Brooks' expert construction is too slick. The storytelling can be a little quaint and even convenient, much in the same way that Albert Brooks' well-timed zingers stand out from the reality of the movie as just being too perfect. Albert is good, but sometimes he appears to know he has a great one-liner. (Ironic how much Aaron Altman absolutely abhors alliteration given his name.) Those who find romantic comedies too predictable probably won't be all that surprised by how the plot twists here, either, not even when Brooks actually breaks from convention.

To that I say so what. Let Broadcast News be flawed, let it have its merry way with genre tropes. That's the compromise enjoying a love story sometimes requires. Let go of your modern conceits, and embrace what is maybe old fashioned about romantic movies. Give your head a rest and let your heart take hold of the remote. Because, damnit, Broadcast News is just so likable, getting mad that it works too well just seems disingenuous. Surrender to the moment, and leave the lonely taxi rides to someone else.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Thursday, January 20, 2011

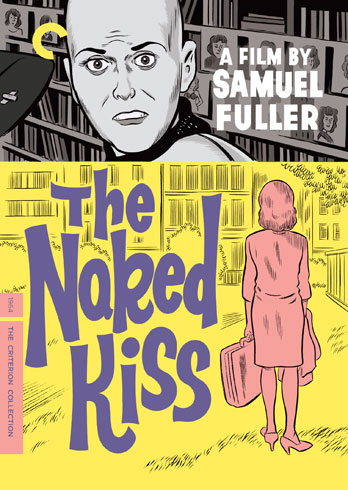

BLU REDO - SHOCK CORRIDOR, THE NAKED KISS, and ROBINSON CRUSOE ON MARS

It's hard to believe I'm only been about three months since I got my Blu-Ray player. I definitely jumped in with both feet, even if I'm trying to be cautious about going overboard with upgrading my entire collection. I'm a boy on a budget, after all.

So, when I say that the new Criterion reissues of their Samuel Fuller titles, Shock Corridor and The Naked Kiss, are absolutely worth it, you can trust that this is something I mean wholeheartedly. Even if you aren't partaking of the new format yet, judging by the new transfers and all-around quality of the packaging, I am sure the standard DVD re-releases are also worth the cash. Being #18 and #19 in terms of spine numbers means both of these films were pretty early in the catalogue's existence. The original release date of the first barebones editions was 1998. Grand strides have been made in the art of film restoration, and you can see the journey in every cleaned-up frame. Both movies look astonishing. The pristine high-definition transfers are free of blemish, and they show the balanced black-and-white photography as never before. Given how much these flicks have been kicked around through the years, with various dubious DVD releases, it's wonderful to have definitive releases that get them exactly right.

I reviewed both of the Fuller movies not that long ago, prior to the announcement of these upgrades. It hasn't been quite enough time for me to develop profound new insights into the films, so you can read those reviews in the archives (Shock Corridor here, The Naked Kiss here). That doesn't mean there isn't plenty to talk about here. These releases are more than just new transfers, but a full overhaul. You can tell that right away when you see the spiffy new covers. Comics artist Daniel Clowes, perhaps best known in film circles as the author of the original Ghost World

Criterion has also added several bonus features that make these Blu-Rays worth the price of admission. I'm particularly excited to report that Shock Corridor now comes with the 1996 documentary The Typewriter, the Rifle and the Movie Camera, a 55-minute profile of Fuller directed by Adam Simon and featuring commentary by Tim Robbins, Martin Scorsese, Jim Jarmusch, and Quentin Tarantino. I first saw this documentary on IFC back in the 1990s, before I had seen most of Fuller's films, if in fact I had seen any. It gave me a long list of movies to seek out, some of which I am still looking for. (Hey, China Gate is on Netflix Instant!) Now that I've seen a good selection of them, it's all the more effective when Robbins and Tarantino go into Fuller's storage garage and sift through his memorabilia; now I actually know what it is they are finding!

More invigorating, though, is the footage of Fuller talking. What a raconteur this guy was! The title refers to his three careers: reporter, soldier (Fuller fought in WWII), and filmmaker. Each phase is covered, all brought to life by Fuller's vivid anecdotes. As Scorsese points out, Fuller tells stories the same way he makes films--there is no difference between what comes out of his mouth and what he puts on the screen. If you like how Sam makes movies, you'll love listening to him. (Side note: Too bad Criterion couldn't also resurrect Tigrero

The bulk of the supplements on The Naked Kiss seize on the concept of Fuller as storyteller and run with it. Three different archival television programs are almost entirely single-camera jobs. Fuller is interviewed in all of them, but they are really more like monologues. The earliest is a 1967 episode of the French television show Cinéastes de notre temps, and it's nearly half-an-hour of vintage Sam. Flanked by the Eiffel Tower, the director lays out a lot of his technique and what excites him about motion pictures. One explanation of a particularly complicated set-up will have you rushing to your Pick-Up On South Street discs to see what he is talking about. [review]

Another French program is a short segment from Cinéma cinemas. Shot in 1987, it's simply Fuller going through a collection of famous photographs and talking about what he remembers. Some pre-date his movie career, including pictures from his wartime service, and others come from the publicity archives of many of his films. His life and history is also a good part of the 1983 episode of The South Bank Show, a BBC program that devoted an installment to the director. About half-an-hour of the full episode is excerpted here. Most of it, again, is Sam, but there is a small portion with Wim Wenders sharing his thoughts about Fuller.

Both BDs also have the original theatrical trailers, and each has nearly half-an-hour of a 2007 interview with actress Constance Towers, who was in both Shock Corridor and The Naked Kiss. She talks in-depth (nearly half an hour on each) about working with Sam and his balls-out production process, and the segments are specific to their particular disc. The interview on The Naked Kiss also includes her sharing more about her background. The story of the girl from Whitefish, Montana, making it in film is a classic Hollywood tale unto itself.

I'm a big Samuel Fuller fan, so these new releases would have likely been a must-have regardless, but seeing as how the Criterion Collection has gone all out in terms of improving them, it's a double-dip I have no residual qualms for indulging in.

Also out this month on Blu-Ray, and alas another film I covered last year, is Byron Haskin's Robinson Crusoe on Mars [original review]. Released in 1964 (the same year as The Naked Kiss), it's a Technicolor wonder--one that definitely seems more charming on second viewing. That could be down to the stunning presentation, I don't know. The original Criterion disc, released just over three years ago, was no slouch in the technical department, but the Blu-Ray shows just how dazzling a movie like this one can be in high-definition.

Though the unschooled might have previously had occasion to sniff at the special effects as being simplistic compared to the complicated pixel-by-pixel build-ups we get today, seeing Robinson Crusoe on Mars in this capacity would shut just about anyone up. The colors are remarkably vibrant, and the added clarity allows every tiny detail to be seen like never before. You'd have to be a hardcore cynic not to be awed by how incredibly complete Haskin's invented world is. The suits, the gadgets, the rockets, even the surface of the red planet--this is a craftsmen's delight. Even if, like me, you weren't immediately in love with Robinson Crusoe on Mars the first time around, the Blu-Ray warrants a second look.

For those wondering, the supplements on this edition are exactly the same as on the standard DVD, as is the packaging. The excellent Bill Sienkiewicz artwork is still intact. It's another thing all of these reissues have in common besides their original theatrical release dates: comic book illustrations. They are movies that capture the imagination, even if they do so in totally different, nearly opposite ways, and capturing the imagination is something a good comic artist knows a thing two about him or herself.

The Naked Kiss and Robinson Crusoe on Mars were provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review. Shock Corridor was reviewed in conjunction with DVD Talk, and you can read the full article here.

Labels:

blu-ray,

Byron Haskin,

Criterion Art,

fuller,

jarmusch,

quentin tarantino,

scorsese,

wim wenders

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

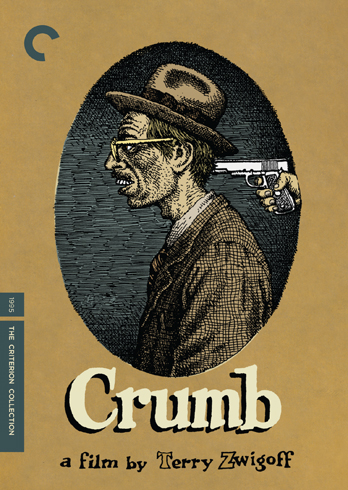

CRUMB (Blu-Ray) - #533

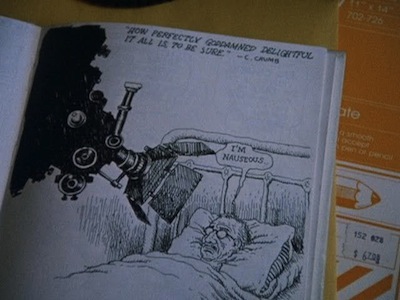

"How perfectly goddamned delightful it all is, to be sure."

There is so much loaded into the above statement by Charles Crumb, that one can't help but immediately seize on it. It is so packed with meaning and says a multitude of things with such poetic economy, Terry Zwigoff had to know immediately upon hearing it that it would serve as ideal punctuation for the epilogue of his 1995 documentary Crumb. What had started out as a film about legendary underground cartoonist Robert Crumb ended up not just a portrait of the artist as a middle-aged man, but of his family as well. The fact that Zwigoff composes the film with such attention to detail, and yet absent of even a whiff of judgment, has made it one of the most compelling documentaries of our times, as well as one of the most perceptive and illuminating examinations of both the perils and giddy joy of the creative life.

Though Charles Crumb is credited with the phrase, Robert Crumb is the one who shares it with Zwigoff, having scribbled it at the top of a drawing he made to illustrate the anxiety the filming process had been causing him. Robert and his wife Aline Kominsky were preparing to move to France at the time, a fitting end to the filmmaking schedule. Zwigoff had asked Robert if he would miss his family or otherwise felt bad about leaving them. The artist says no, he never sees Charles or his mother, and the interview session reminded him why. That quote was a favorite phrase of the older brother's, and he would say it to deflate any happiness his younger siblings might find in anything that struck their fancy. Imagine it said sarcastically. The underlying meaning is that what Robert liked was stupid and liking it made him an idiot.

And yet, it could also be the Crumb family motto, and it need not be as sardonic as all that. There is something strangely American in how off center this American clan is. Imagine Robert Crumb and his brothers standing on a hillside, the sun setting in the sky behind them, at the end of an old Hollywood movie. "How perfectly goddamned delightful it all is, to be sure," is suddenly "As God is my witness, I'll never be hungry again."

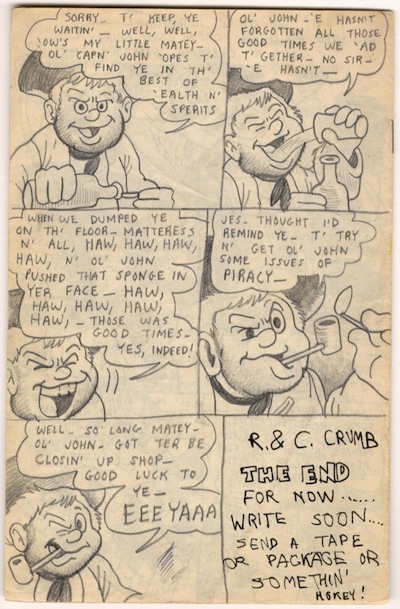

Crumb is a two-hour perusal of the Crumb family photo album. Though a good portion of it does chronicle R. Crumb's rise to infamy as a satirist and counter-culture cartoonist, the full image doesn't really come into frame without the other boys. Robert is the middle child, and the youngest is Maxon. (Two sisters refused to participate in the movie. Can't say I blame them, lord knows what was done to them in that household when they were young.) All three boys possess a natural ability for art, though it was Charles who literally forced them into comic books, particularly Robert, who saved the fruits of their labor all these years. He's got stacks of the fancy books he and Charles put together, trading story lines and ideas, developing their unique style. There is an obsessive-compulsive trait to both of their aesthetics: R. Crumb is known for his meticulous cross-hatching and immaculate ink lines, whereas Charles developed a "wrinkled" style. As he got older, everything he drew was decorated in endless loops.

Maxon's story is slightly different. He started drawing when he was older, and the sudden release of passion resulted in an epileptic seizure. He is more of a fine artist now, but in his paintings, there is a consistent mechanical theme and also a vague obsession with undulating, melting lines, reminiscent of the clocks in Dali's "Persistence of Memory." At the time of filming, Maxon was living a pseudo-monastic life, begging for change in San Francisco. In Crumb's most discussed scene, which comes not long after Maxon has confessed to a misspent youth pulling women's pants down in public, the clearly deranged painter is meditating on a bed of nails while swallowing a chord that he will pass through his digestive track to clean it out. If Charles had the same cord, he would probably wrap it around himself like his beloved wrinkles; for Maxon, it's another undulating line.

Charles lived on the other side of the country. He never moved out of their childhood home, and he has turned into a recluse that never goes outside and only bathes once every six weeks. He's on medication for depression, and he admits to suicide attempts and previous homicidal thoughts. (The sad coda is he did kill himself not long after his interview was filmed.) There is some intimation that maybe Charles, who was a regular troublemaker as a youngster, turned inward to avoid even more dangerous impulses. Many of the comics he made when he was a teen riff on the Treasure Island story--but not because of the escape fantasy the adventure tale offered, but because Charles had become fixated on the young actor Bobby Driscoll, who starred in the 1950 movie version.

story--but not because of the escape fantasy the adventure tale offered, but because Charles had become fixated on the young actor Bobby Driscoll, who starred in the 1950 movie version.

Robert Crumb listens to both his brothers indulgingly, laughing at their quirks, but never in a way that is mean-spirited. Robert has a habit of laughing at just about everything, including himself, though there is a lot of anger inside him. It ends up in his work, in his comic book adventures of Mr. Natural and Devil Girl and the sketches and one-offs he fills into notebook after notebook. One thing that Zwigoff succeeds at with smashing success in Crumb is relaying the subject and timbre of Crumb's comics to the audience. I had only a passing knowledge of the artist when I saw Crumb on its original theatrical release, but watching the film made me feel like I knew the work intimately. Zwigoff does this by just putting the camera lens up to the page and tracking the comic book panels as the artist tells the story behind them or sometimes even just reads the dialogue. The director also peers over the artist's soldier while he sketches in public. It's an unbelievable record of a craftsman at work. (Criterion also does a great job of giving us access to the work of all the artists, filling the interior booklet with efforts from all the brothers and even Robert's son Jesse, as well as giving us a full reproduction of a correspondence school's artist test Robert talks about in the film.)

The comics of R. Crumb are known for their sexual deviancy and anarchic humor, and the creator makes no attempt to hide his fetishes. There is one hilarious scene where the artist poses for a layout in the porn magazine Leg Show, and the editor who set it up, who also happens to be a former girlfriend of Crumb's, hires models that fit his particular bill: thick legs, big butts, and a frame sturdy enough to give him a piggyback ride. In an effort to puzzle out R. Crumb's work, Zwigoff even gives some screen time to his critics. There are cases to be made for misogyny and racism in his comics, ones that Crumb ultimately seems to suggest are unfounded, but Zwigoff lets the detractors have their say all the same.

I think Crumb makes the strongest case for the value of his work himself when he says, essentially, these thoughts had to go somewhere, so why not channel them into art. If you consider what the other Crumb brothers got up to, the notion bears truth. Maybe if Maxon had put his peccadilloes onto more canvases, he wouldn't have gotten into legal hot water for harassing women. Maybe if Charles kept drawing, he'd have found a way to sort out the wrinkles in his own brain. Those are big what-ifs, their illnesses may have gotten the better of them either way, but you still have to wonder.

Because contrary to all the weirdness, Crumb does have some hope and normalcy. Both of Robert Crumb's children, Sophie and Jesse, were burgeoning artists at the time of filming, and Zwigoff shows the father sharing in his children's creations, offering advice and support. Somehow, this new generation appears to be turning out all right despite being a product of the same mad genius. As any creative person will tell you, making our art keeps us from losing our minds. Personally, if I get away from writing for more than a couple of days, my brain doesn't work right. In the case of the Crumbs, the family that draws together, stays sane together.

Visit the official R. Crumb website.

There is so much loaded into the above statement by Charles Crumb, that one can't help but immediately seize on it. It is so packed with meaning and says a multitude of things with such poetic economy, Terry Zwigoff had to know immediately upon hearing it that it would serve as ideal punctuation for the epilogue of his 1995 documentary Crumb. What had started out as a film about legendary underground cartoonist Robert Crumb ended up not just a portrait of the artist as a middle-aged man, but of his family as well. The fact that Zwigoff composes the film with such attention to detail, and yet absent of even a whiff of judgment, has made it one of the most compelling documentaries of our times, as well as one of the most perceptive and illuminating examinations of both the perils and giddy joy of the creative life.

Though Charles Crumb is credited with the phrase, Robert Crumb is the one who shares it with Zwigoff, having scribbled it at the top of a drawing he made to illustrate the anxiety the filming process had been causing him. Robert and his wife Aline Kominsky were preparing to move to France at the time, a fitting end to the filmmaking schedule. Zwigoff had asked Robert if he would miss his family or otherwise felt bad about leaving them. The artist says no, he never sees Charles or his mother, and the interview session reminded him why. That quote was a favorite phrase of the older brother's, and he would say it to deflate any happiness his younger siblings might find in anything that struck their fancy. Imagine it said sarcastically. The underlying meaning is that what Robert liked was stupid and liking it made him an idiot.

And yet, it could also be the Crumb family motto, and it need not be as sardonic as all that. There is something strangely American in how off center this American clan is. Imagine Robert Crumb and his brothers standing on a hillside, the sun setting in the sky behind them, at the end of an old Hollywood movie. "How perfectly goddamned delightful it all is, to be sure," is suddenly "As God is my witness, I'll never be hungry again."

Crumb is a two-hour perusal of the Crumb family photo album. Though a good portion of it does chronicle R. Crumb's rise to infamy as a satirist and counter-culture cartoonist, the full image doesn't really come into frame without the other boys. Robert is the middle child, and the youngest is Maxon. (Two sisters refused to participate in the movie. Can't say I blame them, lord knows what was done to them in that household when they were young.) All three boys possess a natural ability for art, though it was Charles who literally forced them into comic books, particularly Robert, who saved the fruits of their labor all these years. He's got stacks of the fancy books he and Charles put together, trading story lines and ideas, developing their unique style. There is an obsessive-compulsive trait to both of their aesthetics: R. Crumb is known for his meticulous cross-hatching and immaculate ink lines, whereas Charles developed a "wrinkled" style. As he got older, everything he drew was decorated in endless loops.

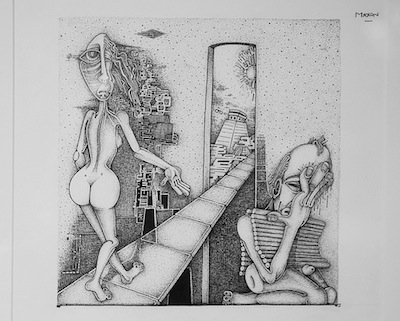

A comic book page by the young Crumbs

Maxon's story is slightly different. He started drawing when he was older, and the sudden release of passion resulted in an epileptic seizure. He is more of a fine artist now, but in his paintings, there is a consistent mechanical theme and also a vague obsession with undulating, melting lines, reminiscent of the clocks in Dali's "Persistence of Memory." At the time of filming, Maxon was living a pseudo-monastic life, begging for change in San Francisco. In Crumb's most discussed scene, which comes not long after Maxon has confessed to a misspent youth pulling women's pants down in public, the clearly deranged painter is meditating on a bed of nails while swallowing a chord that he will pass through his digestive track to clean it out. If Charles had the same cord, he would probably wrap it around himself like his beloved wrinkles; for Maxon, it's another undulating line.

Art by Maxon Crumb

Charles lived on the other side of the country. He never moved out of their childhood home, and he has turned into a recluse that never goes outside and only bathes once every six weeks. He's on medication for depression, and he admits to suicide attempts and previous homicidal thoughts. (The sad coda is he did kill himself not long after his interview was filmed.) There is some intimation that maybe Charles, who was a regular troublemaker as a youngster, turned inward to avoid even more dangerous impulses. Many of the comics he made when he was a teen riff on the Treasure Island

Robert Crumb listens to both his brothers indulgingly, laughing at their quirks, but never in a way that is mean-spirited. Robert has a habit of laughing at just about everything, including himself, though there is a lot of anger inside him. It ends up in his work, in his comic book adventures of Mr. Natural and Devil Girl and the sketches and one-offs he fills into notebook after notebook. One thing that Zwigoff succeeds at with smashing success in Crumb is relaying the subject and timbre of Crumb's comics to the audience. I had only a passing knowledge of the artist when I saw Crumb on its original theatrical release, but watching the film made me feel like I knew the work intimately. Zwigoff does this by just putting the camera lens up to the page and tracking the comic book panels as the artist tells the story behind them or sometimes even just reads the dialogue. The director also peers over the artist's soldier while he sketches in public. It's an unbelievable record of a craftsman at work. (Criterion also does a great job of giving us access to the work of all the artists, filling the interior booklet with efforts from all the brothers and even Robert's son Jesse, as well as giving us a full reproduction of a correspondence school's artist test Robert talks about in the film.)

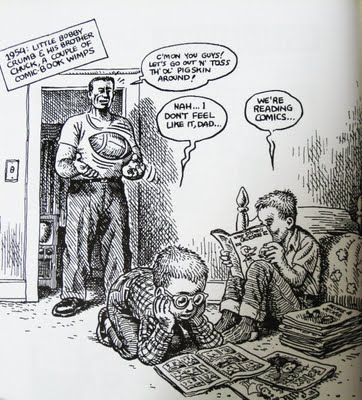

R. Crumb's rendering of his childhood.

The comics of R. Crumb are known for their sexual deviancy and anarchic humor, and the creator makes no attempt to hide his fetishes. There is one hilarious scene where the artist poses for a layout in the porn magazine Leg Show, and the editor who set it up, who also happens to be a former girlfriend of Crumb's, hires models that fit his particular bill: thick legs, big butts, and a frame sturdy enough to give him a piggyback ride. In an effort to puzzle out R. Crumb's work, Zwigoff even gives some screen time to his critics. There are cases to be made for misogyny and racism in his comics, ones that Crumb ultimately seems to suggest are unfounded, but Zwigoff lets the detractors have their say all the same.

I think Crumb makes the strongest case for the value of his work himself when he says, essentially, these thoughts had to go somewhere, so why not channel them into art. If you consider what the other Crumb brothers got up to, the notion bears truth. Maybe if Maxon had put his peccadilloes onto more canvases, he wouldn't have gotten into legal hot water for harassing women. Maybe if Charles kept drawing, he'd have found a way to sort out the wrinkles in his own brain. Those are big what-ifs, their illnesses may have gotten the better of them either way, but you still have to wonder.

Because contrary to all the weirdness, Crumb does have some hope and normalcy. Both of Robert Crumb's children, Sophie and Jesse, were burgeoning artists at the time of filming, and Zwigoff shows the father sharing in his children's creations, offering advice and support. Somehow, this new generation appears to be turning out all right despite being a product of the same mad genius. As any creative person will tell you, making our art keeps us from losing our minds. Personally, if I get away from writing for more than a couple of days, my brain doesn't work right. In the case of the Crumbs, the family that draws together, stays sane together.

Visit the official R. Crumb website.

Thursday, January 13, 2011

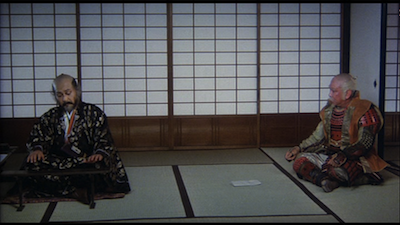

KAGEMUSHA - #267

[Note: This is the longer companion to a short review of Kagemusha I wrote for the Portland Mercury. Look for it in this week's edition, or read it on their blog here.]

Kagemusha is not a young man's film. Released in 1980, it was made when Akira Kurosawa was 70. In the previous 15 years, he had only made two movies--the misunderstood Dodes'ka-den [review] and the Russian-financed Dersu Uzala . Kagemusha was financed in part by a deal with Suntory whiskey and American funding finagled by producers Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas (there are worse ways to throw you weight around than convincing 20th Century Fox to give Akira Kurosawa some money). The Japanese legend had been in a kind of director's jail, and it's hard to say if the time away gave him a new perspective or if this is where he would end up all along. Because Kagemusha is a complex movie, one that is far less cavalier about swordplay and violence than its more famous predecessors.

. Kagemusha was financed in part by a deal with Suntory whiskey and American funding finagled by producers Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas (there are worse ways to throw you weight around than convincing 20th Century Fox to give Akira Kurosawa some money). The Japanese legend had been in a kind of director's jail, and it's hard to say if the time away gave him a new perspective or if this is where he would end up all along. Because Kagemusha is a complex movie, one that is far less cavalier about swordplay and violence than its more famous predecessors.

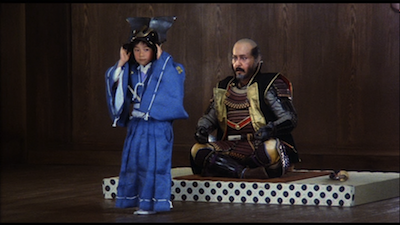

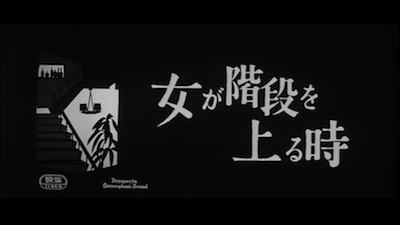

Set in the 16th Century during a time of civil war, Kagemusha is based on real events, but it is also its own fanciful thing. The title translates as "Shadow Warrior," and the script by Kurosawa and Masato Ide is an old man's version of the "Prince and the Pauper" fable. Japanese cinema mainstay Tatsuya Nakadai--he was Mifune's rival in Sanjuro [review] and Yojimbo [review], and also starred in movies like When a Woman Ascends the Stairs [review] and The Human Condition [review]--stars as Shingen Takeda, a warlord with a tenuous hold on Kyoto. He has been fending off two rivals, Nobunaga Oda (Daisuke Ryû) and Ieyasu Tokugawa (Masayuki Yui), both of whom would crush Shingen and take over Japan if given half the chance.

Nakadai also stars in the picture as his own double. At the start of Kagemusha, Shingen's brother Nobukado (Tsutomu Yamazaki) has brought him a thief who was due to be executed. The condemned criminal bears a startling resemblance to the ruler, and Nobukado believes he can prove useful as a decoy to fool his brother's enemies. The thief appears to be an unruly creature--his first order of business is asking why he's the one condemned to die when Shingen has stolen from and killed thousands in the name of "politics"--but his honesty also impresses his benefactor. They decide to keep him around.

Shortly after, Shingen is fatally shot. Before he dies, he informs his cabinet that they should hide his passing for three years while they secure their position against the others. Suddenly, the impostor is put in the seat of power for real. He's reluctant at first. Why should he give up his life for a society that rejected him? He eventually relents, deciding he should honor Shingen for sparing his life and actually stand for something. Slowly, he embraces the role of ruler, going from nervous puppet to self-deluded commander--a move that ultimately causes him to be knocked low by his own hubris. With the three years up, Shingen's former compatriots have no more need for the fake warlord, and they send the thief packing.

But who is the man now that he has given himself to be someone else's shadow? He had found a life in the palace walls, including bonding for real with Shingen's grandson--a relationship that didn't exist when the real Shingen was alive. The child almost blew the whole scheme, having sensed at once that this was not his grandfather. What tipped him off? The fact that the big man no longer scared him. It seems there was some truth to the crook's assertion that he was the better man than the more vaunted warrior.

It's a heartbreaking changeover, though. The shadow accepted his duty without any promise of reward. In shedding his self, he also shed his selfish concerns. Thus, when he is cast out by the people he served--the soldiers he once commanded throw rocks at him to drive him from the compound--he has nowhere to go, no one to be. Ironic, then, when he returns to watch "himself" be buried. When the final clash between the competing armies happens, he spies on the action from the weeds, a peeping tom on the field of battle rather than the powerful presence he had been in the last skirmish. That prior battle was also the point when he lost his way, he started to think he really was the person that the rest of them were scared of. Tatsuya Nakadai is remarkable. He is funny and warm to begin with, but then devastatingly hollow. In some ways, this feels like a dry run for his turn as Lord Ichimonji in Ran [review] five years later, but it's also its own thing. Ichimonji loses himself to madness in order to block out the horrors of the world crumbling around him, whereas the double is all too clear on how everything is going wrong.

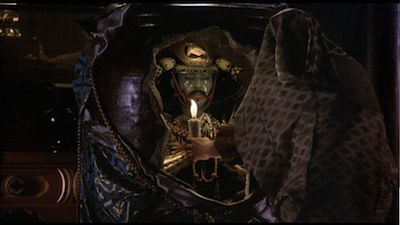

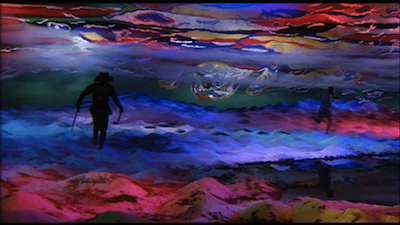

Akira Kurosawa constructed Kagemusha with a formalistic rigidity, which he then tears into with occasional explosions of color and surprising symbolism. In a gaudy dream sequence, the double is chased by his original on a painted background that looks like it was created by Van Gogh during a fit of color blindness. The epically staged war sequences are shot with an expressionistic design, abstracting them in a way that makes them beautiful and yet somehow all the more horrifying. When the pretty smoke clears, and Kurosawa shows us the carnage that lay just underneath, it's sickening to realize the excitement we, as viewers, allowed ourselves to feel. Perhaps knowing we might be immune to fake blood and dead soldiers, Kurosawa mostly focuses on the felled horses, some clinging to life, some fighting to get themselves out of the butchery all around them. This is man's cruelty: we just don't lay waste to ourselves, but to everything around us. The aftermath of the showdown looks like Hell on Earth. Life as we know it is gone.

That's when the thief comes stumbling out of the weeds. In this surreality, he is the only one left to mourn mankind and its folly. This should have been his victory, or even his failure. Instead, he has been removed. His only choice is to charge ahead, a futile final stand. The symbolism of the final shots is staggering: glory has been drowned, and its remnants wash away on a grotesque red tide.

This is the second time I have seen Kagemusha. The first time was when the DVD came out, and this time, it was on a movie screen. I don't think the difference in viewing experiences is why I rate it higher than I did prior. On my first viewing, I liked it fine, but it didn't strike me as heavy as it did the second time. That's possibly because there is a lot to keep straight in this movie. The political intrigue that fuels not just the civil war, but that also orchestrates the whole doppelganger scheme, can get pretty complicated. There are so many characters, it's kind of one of those "you can't tell the players without a program" situations. (Thankfully, Kurosawa helpfully introduces each character with a caption as they appear.) On the first time through, it can be hard to separate that part of the story from the richer personal drama, something I was able to do when giving it another look.

That said, the 35mm print I was lucky enough to watch this time around was marvelous. Any scratches or spots were few and far between, and the rich colors and dynamic sound were a pleasure to partake. Kagemusha is a film writ large to begin with, so actually seeing it in the large theatrical format is a real treat. I am not sure how extensively this print is currently touring the country, but Portland's fantastic independent theatre Cinema 21 has it for four days, January 14 to the 17th. This is the same place that gave us a big-screen Ran only a few months ago. I suppose it would be too much to ask that you guys keep working backward through the Kurosawa filmography? I'd love to come out and see Dersu Uzala in a couple of months if you do!

One final note: Those Suntory commercials, which were actually directed by Francis Ford Coppola, are included on the DVD, alongside a short documentary about Kurosawa's connection to the American filmmakers who helped him out. These commercials would later go on to inspire Sofia Coppola to use Suntory whiskey spots as the reason Bob Campbell (Bill Murray) goes to Tokyo in Lost in Translation [review].

Kagemusha is not a young man's film. Released in 1980, it was made when Akira Kurosawa was 70. In the previous 15 years, he had only made two movies--the misunderstood Dodes'ka-den [review] and the Russian-financed Dersu Uzala

Set in the 16th Century during a time of civil war, Kagemusha is based on real events, but it is also its own fanciful thing. The title translates as "Shadow Warrior," and the script by Kurosawa and Masato Ide is an old man's version of the "Prince and the Pauper" fable. Japanese cinema mainstay Tatsuya Nakadai--he was Mifune's rival in Sanjuro [review] and Yojimbo [review], and also starred in movies like When a Woman Ascends the Stairs [review] and The Human Condition [review]--stars as Shingen Takeda, a warlord with a tenuous hold on Kyoto. He has been fending off two rivals, Nobunaga Oda (Daisuke Ryû) and Ieyasu Tokugawa (Masayuki Yui), both of whom would crush Shingen and take over Japan if given half the chance.

Nakadai also stars in the picture as his own double. At the start of Kagemusha, Shingen's brother Nobukado (Tsutomu Yamazaki) has brought him a thief who was due to be executed. The condemned criminal bears a startling resemblance to the ruler, and Nobukado believes he can prove useful as a decoy to fool his brother's enemies. The thief appears to be an unruly creature--his first order of business is asking why he's the one condemned to die when Shingen has stolen from and killed thousands in the name of "politics"--but his honesty also impresses his benefactor. They decide to keep him around.

Shortly after, Shingen is fatally shot. Before he dies, he informs his cabinet that they should hide his passing for three years while they secure their position against the others. Suddenly, the impostor is put in the seat of power for real. He's reluctant at first. Why should he give up his life for a society that rejected him? He eventually relents, deciding he should honor Shingen for sparing his life and actually stand for something. Slowly, he embraces the role of ruler, going from nervous puppet to self-deluded commander--a move that ultimately causes him to be knocked low by his own hubris. With the three years up, Shingen's former compatriots have no more need for the fake warlord, and they send the thief packing.

But who is the man now that he has given himself to be someone else's shadow? He had found a life in the palace walls, including bonding for real with Shingen's grandson--a relationship that didn't exist when the real Shingen was alive. The child almost blew the whole scheme, having sensed at once that this was not his grandfather. What tipped him off? The fact that the big man no longer scared him. It seems there was some truth to the crook's assertion that he was the better man than the more vaunted warrior.

It's a heartbreaking changeover, though. The shadow accepted his duty without any promise of reward. In shedding his self, he also shed his selfish concerns. Thus, when he is cast out by the people he served--the soldiers he once commanded throw rocks at him to drive him from the compound--he has nowhere to go, no one to be. Ironic, then, when he returns to watch "himself" be buried. When the final clash between the competing armies happens, he spies on the action from the weeds, a peeping tom on the field of battle rather than the powerful presence he had been in the last skirmish. That prior battle was also the point when he lost his way, he started to think he really was the person that the rest of them were scared of. Tatsuya Nakadai is remarkable. He is funny and warm to begin with, but then devastatingly hollow. In some ways, this feels like a dry run for his turn as Lord Ichimonji in Ran [review] five years later, but it's also its own thing. Ichimonji loses himself to madness in order to block out the horrors of the world crumbling around him, whereas the double is all too clear on how everything is going wrong.

Akira Kurosawa constructed Kagemusha with a formalistic rigidity, which he then tears into with occasional explosions of color and surprising symbolism. In a gaudy dream sequence, the double is chased by his original on a painted background that looks like it was created by Van Gogh during a fit of color blindness. The epically staged war sequences are shot with an expressionistic design, abstracting them in a way that makes them beautiful and yet somehow all the more horrifying. When the pretty smoke clears, and Kurosawa shows us the carnage that lay just underneath, it's sickening to realize the excitement we, as viewers, allowed ourselves to feel. Perhaps knowing we might be immune to fake blood and dead soldiers, Kurosawa mostly focuses on the felled horses, some clinging to life, some fighting to get themselves out of the butchery all around them. This is man's cruelty: we just don't lay waste to ourselves, but to everything around us. The aftermath of the showdown looks like Hell on Earth. Life as we know it is gone.

That's when the thief comes stumbling out of the weeds. In this surreality, he is the only one left to mourn mankind and its folly. This should have been his victory, or even his failure. Instead, he has been removed. His only choice is to charge ahead, a futile final stand. The symbolism of the final shots is staggering: glory has been drowned, and its remnants wash away on a grotesque red tide.

This is the second time I have seen Kagemusha. The first time was when the DVD came out, and this time, it was on a movie screen. I don't think the difference in viewing experiences is why I rate it higher than I did prior. On my first viewing, I liked it fine, but it didn't strike me as heavy as it did the second time. That's possibly because there is a lot to keep straight in this movie. The political intrigue that fuels not just the civil war, but that also orchestrates the whole doppelganger scheme, can get pretty complicated. There are so many characters, it's kind of one of those "you can't tell the players without a program" situations. (Thankfully, Kurosawa helpfully introduces each character with a caption as they appear.) On the first time through, it can be hard to separate that part of the story from the richer personal drama, something I was able to do when giving it another look.

That said, the 35mm print I was lucky enough to watch this time around was marvelous. Any scratches or spots were few and far between, and the rich colors and dynamic sound were a pleasure to partake. Kagemusha is a film writ large to begin with, so actually seeing it in the large theatrical format is a real treat. I am not sure how extensively this print is currently touring the country, but Portland's fantastic independent theatre Cinema 21 has it for four days, January 14 to the 17th. This is the same place that gave us a big-screen Ran only a few months ago. I suppose it would be too much to ask that you guys keep working backward through the Kurosawa filmography? I'd love to come out and see Dersu Uzala in a couple of months if you do!

One final note: Those Suntory commercials, which were actually directed by Francis Ford Coppola, are included on the DVD, alongside a short documentary about Kurosawa's connection to the American filmmakers who helped him out. These commercials would later go on to inspire Sofia Coppola to use Suntory whiskey spots as the reason Bob Campbell (Bill Murray) goes to Tokyo in Lost in Translation [review].

Labels:

francis ford coppola,

kurosawa,

Sofia Coppola

Tuesday, January 11, 2011

ARMY OF SHADOWS revisted on Blu-Ray - #385

"I'd like viewers to come away from my films unsure whether they've understood them." - Jean-Pierre Melville

The reward of watching movies multiple times is being able to approach the material from different angles. This is my third format for seeing Jean-Pierre Melville's Army of Shadows--I first saw it in its theatrical re-release, then on DVD (my original thoughts are here), and now Blu-Ray--and this time, when I was watching, I paid attention to what a spooky movie Army of Shadows can be. That title, referring to the men who led the French Resistance in WWII, evokes the image of a spectral force, and the world Melville creates for them to go through is akin to a haunted realm, the place of the undead. It's moody and gray, quiet. We visit prison camps, occupied hotels, seaside hideaways, and in each place, normal life doesn't appear to be carrying on as always. The streets lack vibrancy, glimpses of the way things were are fleeting and far away.

And in this wartime limbo, the freedom fighters operate as a separate society, a hidden military. They work in secret, though their actions eventually go public. They seem to move in between the moments in which the rest go about their business--the rest being either their enemy or the citizens they hope to liberate. They are shades. They are other. Their multiple voiceovers speak in past tense, voices from beyond the grave.

Made in 1969, Army of Shadows is the story of the heroic struggle against the Nazis, who occupied France through most of the war. Lino Ventura (Touchez pas au grisbi [review]) plays Philippe Gerbier, one of the main players in this underground revolution. At the start of the movie, he's being taken to a camp for political undesirables. He is driven through rain, out to a remote locale, far from the world. One could argue this is the point where he is separated from reality as it had been known. He is sent to the limbo that precedes limbo, the waiting room for the halfway point. He plots an escape, but before he can make his break, his number is called and he's taken back to the city. Once he is among the SS, he slips always is if he were never really there. The spook has returned to his haunted country.

What follows is a series of "incidents" and "missions." Philippe gathers his troops. Amusingly, it's almost like a manicured Hollywood war team--a brute, a young man, an old man, a handsome guy, a woman who really has it together. They engage in a somber combat, their actions almost imperceptible. There is the gut-clenching pain of having to kill a traitor by hand, and the delivery of supplies through tightly guarded checkpoints, and even a trip to England to try to garner support. There the otherness is even reinforced: during an air raid, Philippe stumbles into a nightclub where British soldiers are dancing. The revelers don't even notice he is there. They barely notice the bombing. They have found an oasis from the war. This is another world: Philippe and his "Chief" (Paul Meurisse) go to see Gone with the Wind . To the boss, a signal that the war is over will be when his countrymen can also experience this cinema--itself another story of struggle and division (though about as far afield of Army of Shadows in terms of tone and style as you're likely to find).

. To the boss, a signal that the war is over will be when his countrymen can also experience this cinema--itself another story of struggle and division (though about as far afield of Army of Shadows in terms of tone and style as you're likely to find).

Melville plays with distance throughout Army of Shadows. Not only is the commonplace now far away, but these people who are working together are also separate, working under fake names, avoiding sharing details of their past lives. He creates formal compositions to mirror the exactitude of their planning. He foregrounds and backgrounds characters on the screen to indicate their current mood. For instance, when Jean-Francois (Jean-Pierre Cassel) decides to distance himself further, Melville puts him in the extreme foreground, away from the rest. The camera eye probes scenes, such as in the prison when Philippe passes around his cigarettes, and director of photography Pierre Lhomme circles with the packet, watching its journey. Melville also concocts an ironic ruse, showing Philippe working out of a talent agency, using theatrics as a front. All of these resistance fighters are performers themselves, they all have distinct roles to play.

Army of Shadows is essentially an espionage picture. It's not a war movie, even though it does involve the war. Rather, this is about the often unsung heroes, the ones who never got their due, who slowly pushed the rock up the mountain to try to make a difference. It's about tough choices and careful maneuvers. The narrative is multi-layered, complex to the point of abstraction. It's not an A to B to C plot in that each sequence suggests the next. Instead, Melville, who wrote the script from a novel by Joseph Kessel, focuses on the unexpected, the developments no one planned for.

Fittingly, then, it's the everyday things that cause the most trouble. For instance, Mathilde (played by the great Simone Signoret) runs afoul of the Nazis because of a photo of her daughter she refuses to discard. Philippe also gets arrested because he's found having a meal in a restaurant that serves black market meat. It's almost like he forgot that this kind of place, sitting with others and having a meal, isn't for him anymore. It leads to Army of Shadow's most existential moment, where Philippe goes against his own self-belief and must question why everyone else knew what he would do better than he did. The Nazi guards at the prison cruelly line up their prisoners and tell them to run. If they can outrun the bullets, they will live to race death again. Philippe tells himself he will not go, but something else takes over. Fear? A survival instinct? Or maybe fate...?

Francois also makes an existential choice in the movie, but he does it in secret. He doesn't even tell his comrades. He lets himself get captured, and they think he's run off. It's a perfect example of the kind of heroism I've been trying to describe. Doing what you think is right for you, and for no other reward but being true to yourself. It's an act born of alienation, but turning that lonely dread to positive action, the kind of ideal existential expression that is often glossed over by those who misunderstand the philosophy. In Philippe's moment of crisis, Melville cuts away from him and shows the actual shadows passing on the wall, the flickering figures of the titular army. One could bring up Plato's Cave, or even return to the theatricality and the whole concept of "shadowplay." Instead, I think this brief image is as straightforward in its symbolism as it seems: our experience is fleeting and difficult, but if we stand away and look at the outline of who we are, we can truly see ourselves. The true army of shadows is the congress of man, inconsequential and disconnected, but marching forward nonetheless.

Criterion's 2007 DVD of Army of Shadows was one of their strongest entries in the SD format, earning high marks from me back when it was released. I'm pleased that the new HD transfer of the 2004 restoration actually improves somewhat on the original release. The changes are subtle, but they manifest in the clarity of detail and the rendering of the colors. This is a very soft movie, taking place in perpetually cloudy weather. The dour grays and blues and the hazy pallor that hangs over everything is chillier here. I wouldn't call it more pronounced, that seems counter-intuitive, but it does have a stronger overall emotional atmosphere.

You can really notice it in the scenes of nature. The opening shots of the rainstorm are striking for how much rain we see, whereas the nighttime escape on the beach later on reveals all sorts of color gradients in the water and the sky. There is more nuance to both surfaces, and our eyes can now track the changes. Later, walks in the park give us nice greens. The actors also benefit, with skin tones and the lines on their face bringing their expressions to the fore, an important thing in a movie where so much occurs in silence.

The original mono soundtrack is presented here in an uncompressed format, while there is also a second choice of stereo mix in DTS. I moved back and forth between them and didn't notice too much difference, though at times the stereo actually did sound more open, like there was a defined space between the two channels.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

The reward of watching movies multiple times is being able to approach the material from different angles. This is my third format for seeing Jean-Pierre Melville's Army of Shadows--I first saw it in its theatrical re-release, then on DVD (my original thoughts are here), and now Blu-Ray--and this time, when I was watching, I paid attention to what a spooky movie Army of Shadows can be. That title, referring to the men who led the French Resistance in WWII, evokes the image of a spectral force, and the world Melville creates for them to go through is akin to a haunted realm, the place of the undead. It's moody and gray, quiet. We visit prison camps, occupied hotels, seaside hideaways, and in each place, normal life doesn't appear to be carrying on as always. The streets lack vibrancy, glimpses of the way things were are fleeting and far away.

And in this wartime limbo, the freedom fighters operate as a separate society, a hidden military. They work in secret, though their actions eventually go public. They seem to move in between the moments in which the rest go about their business--the rest being either their enemy or the citizens they hope to liberate. They are shades. They are other. Their multiple voiceovers speak in past tense, voices from beyond the grave.

Made in 1969, Army of Shadows is the story of the heroic struggle against the Nazis, who occupied France through most of the war. Lino Ventura (Touchez pas au grisbi [review]) plays Philippe Gerbier, one of the main players in this underground revolution. At the start of the movie, he's being taken to a camp for political undesirables. He is driven through rain, out to a remote locale, far from the world. One could argue this is the point where he is separated from reality as it had been known. He is sent to the limbo that precedes limbo, the waiting room for the halfway point. He plots an escape, but before he can make his break, his number is called and he's taken back to the city. Once he is among the SS, he slips always is if he were never really there. The spook has returned to his haunted country.

What follows is a series of "incidents" and "missions." Philippe gathers his troops. Amusingly, it's almost like a manicured Hollywood war team--a brute, a young man, an old man, a handsome guy, a woman who really has it together. They engage in a somber combat, their actions almost imperceptible. There is the gut-clenching pain of having to kill a traitor by hand, and the delivery of supplies through tightly guarded checkpoints, and even a trip to England to try to garner support. There the otherness is even reinforced: during an air raid, Philippe stumbles into a nightclub where British soldiers are dancing. The revelers don't even notice he is there. They barely notice the bombing. They have found an oasis from the war. This is another world: Philippe and his "Chief" (Paul Meurisse) go to see Gone with the Wind

Melville plays with distance throughout Army of Shadows. Not only is the commonplace now far away, but these people who are working together are also separate, working under fake names, avoiding sharing details of their past lives. He creates formal compositions to mirror the exactitude of their planning. He foregrounds and backgrounds characters on the screen to indicate their current mood. For instance, when Jean-Francois (Jean-Pierre Cassel) decides to distance himself further, Melville puts him in the extreme foreground, away from the rest. The camera eye probes scenes, such as in the prison when Philippe passes around his cigarettes, and director of photography Pierre Lhomme circles with the packet, watching its journey. Melville also concocts an ironic ruse, showing Philippe working out of a talent agency, using theatrics as a front. All of these resistance fighters are performers themselves, they all have distinct roles to play.

Army of Shadows is essentially an espionage picture. It's not a war movie, even though it does involve the war. Rather, this is about the often unsung heroes, the ones who never got their due, who slowly pushed the rock up the mountain to try to make a difference. It's about tough choices and careful maneuvers. The narrative is multi-layered, complex to the point of abstraction. It's not an A to B to C plot in that each sequence suggests the next. Instead, Melville, who wrote the script from a novel by Joseph Kessel, focuses on the unexpected, the developments no one planned for.

Fittingly, then, it's the everyday things that cause the most trouble. For instance, Mathilde (played by the great Simone Signoret) runs afoul of the Nazis because of a photo of her daughter she refuses to discard. Philippe also gets arrested because he's found having a meal in a restaurant that serves black market meat. It's almost like he forgot that this kind of place, sitting with others and having a meal, isn't for him anymore. It leads to Army of Shadow's most existential moment, where Philippe goes against his own self-belief and must question why everyone else knew what he would do better than he did. The Nazi guards at the prison cruelly line up their prisoners and tell them to run. If they can outrun the bullets, they will live to race death again. Philippe tells himself he will not go, but something else takes over. Fear? A survival instinct? Or maybe fate...?

Francois also makes an existential choice in the movie, but he does it in secret. He doesn't even tell his comrades. He lets himself get captured, and they think he's run off. It's a perfect example of the kind of heroism I've been trying to describe. Doing what you think is right for you, and for no other reward but being true to yourself. It's an act born of alienation, but turning that lonely dread to positive action, the kind of ideal existential expression that is often glossed over by those who misunderstand the philosophy. In Philippe's moment of crisis, Melville cuts away from him and shows the actual shadows passing on the wall, the flickering figures of the titular army. One could bring up Plato's Cave, or even return to the theatricality and the whole concept of "shadowplay." Instead, I think this brief image is as straightforward in its symbolism as it seems: our experience is fleeting and difficult, but if we stand away and look at the outline of who we are, we can truly see ourselves. The true army of shadows is the congress of man, inconsequential and disconnected, but marching forward nonetheless.

Criterion's 2007 DVD of Army of Shadows was one of their strongest entries in the SD format, earning high marks from me back when it was released. I'm pleased that the new HD transfer of the 2004 restoration actually improves somewhat on the original release. The changes are subtle, but they manifest in the clarity of detail and the rendering of the colors. This is a very soft movie, taking place in perpetually cloudy weather. The dour grays and blues and the hazy pallor that hangs over everything is chillier here. I wouldn't call it more pronounced, that seems counter-intuitive, but it does have a stronger overall emotional atmosphere.

You can really notice it in the scenes of nature. The opening shots of the rainstorm are striking for how much rain we see, whereas the nighttime escape on the beach later on reveals all sorts of color gradients in the water and the sky. There is more nuance to both surfaces, and our eyes can now track the changes. Later, walks in the park give us nice greens. The actors also benefit, with skin tones and the lines on their face bringing their expressions to the fore, an important thing in a movie where so much occurs in silence.

The original mono soundtrack is presented here in an uncompressed format, while there is also a second choice of stereo mix in DTS. I moved back and forth between them and didn't notice too much difference, though at times the stereo actually did sound more open, like there was a defined space between the two channels.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Wednesday, January 5, 2011

WHEN A WOMAN ASCENDS THE STAIRS - #377

The news went around on Monday that beloved Japanese actress Hideko Takamine had died, having lived a full life. She was 86. Takamine appeared in a staggering number of movies--177, according to IMDB. Her first was in 1929, her last in 1979. I'll admit, I haven't seen most of them. My hat is off to anyone who has. I think I've only seen the ones released by Criterion, with the most memorable for me being Keisuke Kinoshita's Twenty-Four Eyes [review]. In that film, Takamine played a young schoolteacher whose modern ways clashed with the small-town values of the village where she was assigned a school house, and who struggles to take care of the children in her care. It's a performance that is full of heart. Children are supposed to fall in love with their teachers, and as viewers, we fall in love with Takamine.

Hideko Takamine made quite a few movies with Mikio Naruse, including one of his most famous, the 1960 drama When A Woman Ascends the Stairs. As the only film in my library starring Takamine that I hadn't seen, it seemed appropriate to give it a look in honor of the actress' passing. When A Woman Ascends the Stairs is a sad film, though one that is never overly dramatic--even if some of its plot twists are straight soap opera. It also doesn't wallow. Takamine lends her character a plucky spirit that somehow spins all the bad events into a hopeful tapestry celebrating human resilience. The bar hostess Mama Keiko is a long way from the schoolteacher Hisako Oishi is terms of profession, but not in personality or allure. They are almost the same woman, especially as Oishi has seen a few things by the end of Twenty-Four Eyes. Both know heartbreak, but both have the strength to take care of themselves.

When A Woman Ascends the Stairs is set in the Ginza district, a post-War neighborhood where businessmen congregated to drink and carouse. There, the streets were lined with bars that featured women on staff as "hostesses." Their job was to entertain the customers and encourage them to buy drinks. Some extended their duties to after hours, either selling themselves one night at a time or becoming full-time mistresses.