To spectral hand

To Claude Brasseur

Blah blah blah"

-- Morrissey, "At Last I am Born"

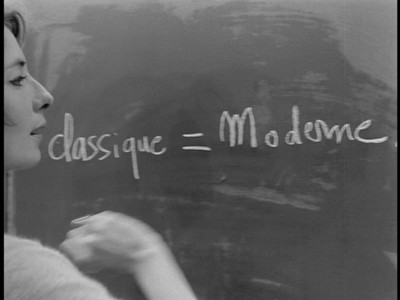

Jean-Luc Godard's Band of Outsiders (Band a part) has been gaining in reputation over the years as one of his most playful self-reflexive genre benders, a riff on a Fritz Lang film noir

As with most of Godard's genre deconstructions, Band of Outsiders has a plot of sorts. Two thugs--the physical Arthur (Claude Brasseur) and the more sensitive Franz (Sami Frey)--vie for the affection of Odile (Anna Karina), both because she is cute as can be and because her miserly uncle keeps a fortune hidden in his big house on the outskirts of town. Odile is cold yet interested, not necessarily committal but not entirely aloof. As with anything, the guy who pushes the issue has the most success, and so Arthur has the edge on Franz. One can bully in romance just as one can be a bully in anything else. It's also Arthur who pushes hardest for the crime, and Odile and Franz must just go along, even as it is clear that they are heading for disaster.

Like any heist film, more time is spent on the planning than the robbery itself. In the case of Band of Outsiders, though, the gang doesn't sit and pour over plans as much as they sit and pour over each other. The preamble to the act involves a lot of sitting around and waiting, of biding their time as if they are at a job and waiting for the boss to leave for the day. Here is where Godard gets most of his kicks. It's in these moments of boredom where inspiration can blossom. Thus, we get the trio dancing "the Madison" in a cafe, framed like a pause in the film, a momentary aside (and later to inspire Quentin Tarantino, whose production company's name is a play on the movie's French title). We also get the famous scene where they see how fast they can race from one end of the Louvre to another.

In the end, the outcome Godard provides for his characters is like an affirmation of their choices. Franz and Odile are more adaptable, subject to change, more in tune with the demands of the heart, whereas Arthur must plow forward like a bull intent on the single target, even as it becomes more evident that doom lurks in the background. Though Arthur's fate is just as much a staple of gangster movies as Odile and Franz's fate, it is also the more real, fulfilling its own promise. As for the others, Godard tells us they will have a happy ending that is generally only found at the end of a Hollywood production, and they will have an ever after seen in a sequel that there was likely never any serious intention to make. It's as if riding off into the sunset is more final than the alternative, or perhaps just unreachable. Only in Hollywood, not anywhere else, and not amongst the self-invented wannabes of a B-movie love story from France.

This was prepared as part of my review of the boxed set 10 Years of Rialto Pictures for DVDTalk.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment