Paul Schrader's 1985 biopic of the Japanese author Yukio Mishima, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, is a thoughtful and inventive examination of a writer's life and how it both influences and is influenced by his work. It's a rare case of a willfully arty film that manages to make the question of style over substance immaterial, as they ultimately are one and the same.

As the title suggests, Mishima is broken into four sections, each meant to portray an important stage in the author's life and show the progression of his ideas toward the extreme activist he would eventually become. Each chapter begins with a "present day" sequence that takes place on November 25, 1970, the day Mishima (played by Ken Ogata, recently seen in The Hidden Blade

From these scenes of Mishima on his way to his mission, Schrader shifts each of the first three chapters into the writer's past. Starting with the boy at age 5 (Yuki Nagahara) and working his way forward into his teen years, and then into his artistic triumphs and adulthood. The flashbacks are all filmed in black-and-white, which serves to differentiate them from the second stories. In addition to the flashbacks, Schrader also chooses one of Mishima's many novels that best exemplifies that period of the work, and he creates a miniature adaptation of said work.

The story begins with chapter 1, "Beauty," where the awkward young boy grows into a man, looking to change his position as a misfit in this world and embrace love and the goodness that life has to offer, the things that are beauty personified. For this section, Schrader chooses to adapt the 1953 novel The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, the story of a Buddhist acolyte (Yasosuke Bando) with a severe stuttering problem whose "deformity" prevents him from finding love, forcing him to always remain separate. He fixates on the golden temple where he is studying and eventually becomes intent on its destruction. Turning it to rubble blots out the false promise he can never fulfill. This action actually teaches him something about beauty, about how it's best to halt it at its apex rather than let age diminish its luster.

From there, Schrader moves to chapter 2, "Art," where Mishima, tasting his first blush of success, begins to ponder how to resolve the false and finite nature of beauty and realize the artist's purpose of preserving said beauty. In his novel Kyoko's Place a young actor turned body builder (Kenji Sawada) realizes that despite his personal perfection, bodies decay. Art is nice, but it requires no sacrifice. He enters into an abusive relationship with a female gangster (Setsuko Karasuma) who begins to use his body as a living sculpture. Real blood is a greater expression of true beauty and art than the false blood spilled on a theatrical stage.

This lesson informs chapter 3, "Action," where Mishima begins to question his role in the world. Words can express ideas, but like how beauty without art fades, so too do ideas go nowhere without action to back them up. The novel for this section is Runaway Horses, a later work about a young soldier (Toshiyuki Nagashima) who forms a cabal of like-minded youths to stage a revolution and restore Japan's honor. As his plan falls apart, he tries one last action before turning his sword on himself. Here the fiction dovetails nicely with the reality, as we go into chapter 4, "Harmony of Pen and Sword," which concerns itself entirely with Mishima's last day on Earth, along with commentary taken from his last book of personal writing, Sun and Steel. (Again, fiction gives way to reality--though reality as seen by Yukio Mishima.)

Each of the novel adaptations is filmed in a colorful, abstract style that borrows from classical and contemporary theatre. Golden Pavilion is the most abstracted, with the sets being obvious facades, while Kyoko reflects a more neon and illusory 1950s. As Schrader moves the timeline forward, each style gets a little more realistic, until it collides with the reality of Mishima's story and the actions of the Shield Society. All of the chapters show the parallels between the writer's life and his fictions, with his childhood struggles to be understood transforming into the acolyte's stuttering, his destruction of canonized literary stylizations being his razing of the Golden Pavilion. So, too, is he later a stage actor, a body builder, and the revolutionary soldier, as the man of letters wrestles with his self-image and the truth of his self-expression.

It's as deep as I've seen anyone go into the life of an artist, certainly multiple steps up from the overly obvious moments of inspiration we see in modern biopics of creative types of various stripes. Schrader and his co-writers, Leonard Schrader (his brother) and the Japanese adapter Chieko Schrader (his sister-in-law), are searching for the true connections, going beyond the standard tale of one life and digging deep into material to show how the writer lives many different existences. He borrows from real events to inform his fiction, but then must alter his life to live up to the ideal he created for himself.

Through it all, Mishima's obsession with death is clear. From his missed opportunity to die for his country in WWII (his own surprising cowardice haunting him ever since) and his study of samurai texts, he begins to dream of an exit that has greater meaning than passing away from old age while home in bed. If action is the only way to give ideas true meaning, then the final action must matter, too.

Though ostensibly an American production--Mishima was produced by George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola for Coppola's Zoetrope Studios--the film was shot entirely in Tokyo using Japanese actors speaking Japanese. The distinctive costume and production design was also by a Japanese artisan, Eiko Ishioka, who prior to this had worked in mediums other than film, but has since gone on to design costumes for Bram Stoker's Dracula and The Cell

It's a bizarre contradiction. The author's work is still venerated in his home country, so why must his life be taboo? Could the irony be that in the act Mishima saw as his final achievement of his artistic ideal, he actually boomeranged back to being the outcast?

Criterion releases Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters as a double-disc set in conjunction with its separate release of the short film Mishima wrote, directed, and starred in himself. 1966's Patriotism adapts a short story he wrote about a soldier and his wife committing seppuku in 1936, and two scenes about the filming and release of Patriotism are included in Mishima. For information about Patriotism, read my review of it here.

Though Mishima was released on DVD by Warner Bros. in 2001, it has been out of print for some time. That disc generally got very high marks. There have been some changes made between the transfer seven years ago and the new one, however, some of which will be up to debate as far as what some people might prefer, but all of which are approved by Paul Schrader and cinematographer John Bailey, so ultimately you'll have to take it up with them.

The most notable change, and the one that should make just about everyone happy is that the old transfer was a 1.75:1 aspect ratio, and the Criterion disc restores the film to its original ratio of 1.85:1, meaning more information now appears on screen. There have been some color changes and digital enhancements made to some scenes on Schrader's insistence, and these will only be noticeable to those who know the old DVD by heart. Overall, I thought this transfer looked pretty good, with the distinctive color schemes popping in all the right ways and none of the pixilation that sometimes marred the older release.

2001

2008

2001

2008

Overall, I think the colors of the movie pop way more in the new version, while the old one looks faded and grainy by comparison.

The original Japanese soundtrack has been mixed in Dolby Digital stereo and sounds very good. Philip Glass' marvelous score for the picture is the true test of any mix of this movie, and his orchestration rings through loud and clear.

There are a couple of alternate audio options for viewers to choose from. There were several versions of the narration recorded for the movie. The default option is the Japanese language narration, but you can also choose the late Roy Scheider's English voiceover that was included in the theatrical release or Paul Schrader's somewhat different voiceover recorded as a guide track for Scheider (available here for the first time; the other two options were on the old DVD).

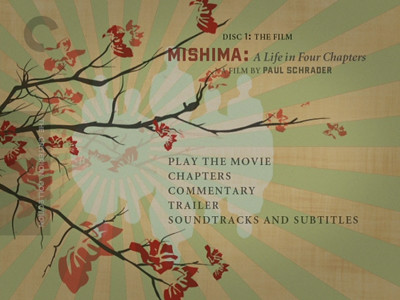

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters - Criterion Collection is a beautiful art object unto itself. Really, Criterion deserves a round of applause for this one. Designer Neil Kellerhouse, along with co-art director Sarah Habibi, has created a bright, embossed boxed set that is as garishly distinctive as Eiko Ishioka's set design and that also plays on the puzzle element of the movie's structure. The outer slipcase has enough room to hold both the DVD sleeve and the 56-page book that comes in the set. The four-sided gatefold sleeve has two trays for the DVDs and a breakdown of the four chapters of the movie printed on the inside. The book has photos, credits, a new critical essay by Schrader-expert Kevin Jackson, information on the film's ban in Japan, and an on-set account from Eiko Ishioka.

Sometimes a DVD set comes along where the nature of a unique production is matched by an equally extraordinary DVD package. Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters - Criterion Collection is one of those sets. Paul Schrader's biopic of the controversial and provocative Japanese author works on multiple levels to break down the writer's life, to show how much of it is interior and how fact and fiction blend into one another. From the script to the production design and the music, every stage of this production strove for something special. This new double-disc set peels the curtain back further to show us how they achieved what they did and more about the reality of the subject. This is one other art films should emulate when making their way to DVD. Don't just fill the space, but fill it well--a sentiment Yukio Mishima could likely get behind.

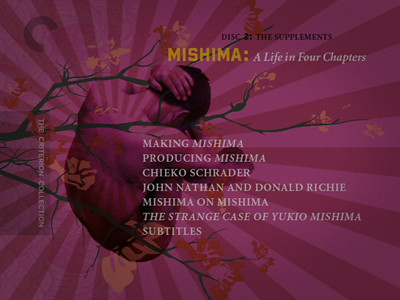

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.