Showing posts with label Sofia Coppola. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Sofia Coppola. Show all posts

Sunday, June 3, 2018

PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK - #29

The biggest strength Peter Weir’s 1985 adaptation of Picnic at Hanging Rock has going for it is its air of mystery, and that atmosphere manages to sustain itself due to the succinctness of Cliff Green’s script and a steady restraint at the helm. Picnic at Hanging Rock has a trim 107-minute running time in which a lot happens, little is explained, and yet we get just enough. Capturing a similar dread would likely be the biggest challenge of Amazon’s current long-form remake. Sure, they likely can extract more from Joan Lindsay’s novel, but will it be at the sacrifice of Weir’s persistent ambiguity?

The story of Picnic at Hanging Rock begins on Valentine’s Day 1900 at an Australian boarding school for girls. As a celebration of the holiday, the students head out on an excursion to a mountainous wilderness marked by its volcanic rock formations. Only one girl, the quiet and brooding Sara (Margaret Nelson), is forbidden to go, held back by the sadistic headmistress (Rachel Roberts) and her strange assistant (Kirsty Child). Late in the afternoon, four of the girls, including Sara’s roommate Miranda (Anne Lambert)--whom Sara and seemingly everyone else is obsessed with--go off exploring on their own. Only one returns, and one of the accompanying teachers (Vivean Gray) likewise vanishes when she goes to retrieve the missing pupils. No one saw a thing. The girls were all napping when the this went down, and perhaps in no small coincidence, the explorers also took a nap at the same time, surrounding a flat rock next to several large totemic outcroppings, like effigies abandoned at Stonehenge. Were there mystical shenanigans going on? Surprisingly, no one ever really suggests it, but there is an aura of a haunting hanging all over Weir’s film.

The rest of Picnic at Hanging Rock is concerned with the lingering questions: where did the girls go? How could there be no clues? The young son of a wealthy General becomes obsessed with the case. The boy (Dominic Guard) and the family servant (John Jarrett) were the last to see the girls before they headed into God knows where. Another teacher chaperoning the trip, a French woman (Helen Morse), tries to hold everyone together, but she starts to see the darkness lurking in the corners of the school. It’s not quite Suspiria-levels of intrigue, but there is something untoward happening behind closed doors all the same. Is this event perhaps some kind of karmic retribution? Or did the girls merely escape a troublesome fate for some kind of unknowable liberation?

It’s easy to see the influence Picnic at Hanging Rock had on Sofia Coppola and The Virgin Suicides [review], from the brown and blond color palette to the way we get to peek behind the veneer of the seemingly trouble-free lives of teenage girls. And that both films fade out with their greatest mysteries still unsolved, they similarly suggest we can never uncover the whole truth. (That is, of course, unless we are one of them. I mean, teenage girls know the whole truth, right?)

Weir’s light touch as a director makes for a fully immersive dream state. Visually, he forces very little, and as a storyteller, he is loath to explain. Often he places his camera at a vantage point that keeps us from fully seeing what is going on. As the young ladies climb into the hills, we peer at them through cracks in the rocks, almost as if Weir is implying that there are spooks and specters--or perhaps just the natural creatures of the Australian outback, which do wander across frame from time to time--keeping watch over the doomed children. Yet, even as we return to civilization, and as the failure to solve the central mystery causes other secrets to be revealed, we always remain just a step outside, as if in a drunken haze, or dreaming ourselves, trapped in the witness position, unable to break through the membrane of our subconscious to become an active participant. Subtly, Weir shifts his colors from the virginal white of the school uniforms that fills every frame of the earliest scenes to much darker colors, the headmistress dressed in black, a symbol of mourning, but also an outward projection of her own sins. It’s interesting, because American school stories would be shifting from spring to summer as the school term ends, giving way to the hopeful promise of a brighter tomorrow, but this is Australia, so the school year ends as winter approaches, suggesting only more dark and cold on the other side. (Though, to be fair, the sunny climes of the continent are nowhere near the bleak winters we’d see in England or on the American east coast.)

The only aspect where Weir nearly pushes things from the ambiguous to the obvious is the music. The score alternates between Zamfir’s pastoral pan flute and ambient electronic music by Bruce Smeaton, the latter of which particularly vibrates with its own sense of “ooooh, isn’t this weird.” Weir’s employment of these tones are often used to shine a light on particular moments where things are supposed to go wrong, or we are supposed to be unnerved; the cues are mostly unnecessary.

While the girls’ disappearance in Picnic at Hanging Rock has the direct result of exposing shady goings-on at the boarding school, there is also a more broad exposure of how society tries to stifle young women entering adulthood. Whenever discussing the health of any of these girls, the first concern is whether or not they were sexually assaulted. The doctor describes them as being “intact.” Yet what do the repressive policies, and the fear of these girls’ emerging sexuality, contribute to the overall scenario? There are the two young men who leer at the girls as they enter the untamed wilds, or the details like the missing teacher seen wandering off without her skirt, or the fact that one girl returns without her corset. Or the strange punishments visited on Sara. How much of this is a result of the prim and proper social mores stifling natural impulses? These are layers that only start to reveal themselves the more you watch, when the details of the disappearing act start to matter less and you can start to appreciate everything going on around it.

Judging by the first episode of the Amazon Picnic at Hanging Rock, there will be some of this subtext at play--but it looks likely to be made overt text. The production looks likely to leave no stone unturned, beginning its initial outing with Mrs. Appleyard (hear played by Natalie Dormer as a much sexier widow) buying the estate that will become her school while confessing to her own false face in voiceover. Oh, goody, an origin story! With a shiny modern style, the series amps up the drama and the adolescence CW-style. The pilot is all preamble and portents, including Edith getting her first period (“You can now have a baby!”) and Appleyard underlining how dangerous the Hanging Rock can be. Jury’s still out if this Picnic at Hanging Rock is any good in its own right (and still out on whether or not I’ll even keep watching; I didn’t feel compelled to hit the “next” button), but for those looking for a similar creepy excursion to Peter Weir’s original adaptation, keep looking.

Sunday, April 22, 2018

THE VIRGIN SUICIDES - #920

Released in 1999, The Virgin Suicides marked the beginning of the career of writer/director Sofia Coppola, who to my mind is the best American filmmaker to emerge in the 21st Century [for more of my reviews of her films, see the links at the end of this article]. Thought not as accomplished as what was to come--and really, all things solidified in Coppola’s second feature, Lost in Translation--this oddly compiled, dreamy coming-of-age tale--or, alternately, a failure to come of age--displayed the promise of everything that was on the way. The ethereal soundtrack, the fascination with sisterhood and youth, and a sense of isolation so contained that it at times feels (and is) otherworldly.

The Virgin Suicides is based on a novel by Jeffrey Eugenides, a male author, which is part of what gives this film such a unique vibe. Though a story with five young women at its center, Eugenides tells it from the point of view of the teenage boys observing them. In its way, it’s stereotypical of memoir-istic first novels of young men, approaching the female of the species as if they are an unknowable riddle. In this case, the boys view the Lisbon Sisters as elusive phantoms--and not just after their deaths, but also before--and even in their adult lives, they can’t shake the influence the sisters had on them. The scenes with a grown-up Trip Fontaine (played by Streets of Fire’s Michael Paré, who is believable as a hard-living adult Josh Harnett) reminiscing on his brief relationship with Lux (Kirsten Dunst, also Coppola’s muse in Marie Antoinette) is like a pitiable version of the Edward Sloane monologue in Citizen Kane. “She didn't see me at all, but I'll bet a month hasn't gone by since that I haven't thought of that girl.”

In her staging of the narrative, Coppola embraces the male gaze while simultaneously jumping to the other side and looking back (particularly, again, where Trip Fontaine is concerned). Her Lisbon Sisters are not a mystery to her, and she is permitting us to view their private lives. As viewers, we are privy to things that the obsessed teen boys never would be, and the secret we share with the Lisbon girls is that we are just aware as they are that their increasingly knowing laughter over the boys’ behavior is justified. The men circling them are silly and obvious, their gaze nearsighted at best. Sadly, it’s also that awareness that means the Lisbon Sisters can’t carry on.

Backing up a bit: for those not familiar with The Virgin Suicides, the story is set in the late 1970s in an upper-middle-class Michigan suburb. Mr. Lisbon (James Woods, Videodrome [review]) is the high school math teacher, and Mrs. Lisbon (Kathleen Turner, Romancing the Stone) is a stay-at-home mom. They are the epitome of square parents who themselves grew up in post-war America (nerdy dad is totally obsessed with WWII aircraft). One can guess a devotion to their Catholic ideals is partly to blame for their having five daughters, each born a year after the next, now aged thirteen to seventeen. A strict upbringing has limited the social interaction the girls have had with the outside world, and the quintet has formed their own solid bond, moving and acting as a single unit, a troop of perfect skin, white teeth, and blonde hair.

After the youngest, Cecilia (Hanna Hall, also the young Jenny in Forrest Gump), attempts to kill herself, it’s recommended that the Lisbons loosen the apron strings. Unfortunately, this doesn’t quite get at what is bothering the sensitive young teen, and as their attempts to be more open go wrong, the parents clamp down harder. Put under permanent house arrest, the girls grow even more distant and more insular, while the neighborhood boys start to plot ways to communicate with them and, ultimately, save them.

The Virgin Suicides has the dreamy air of youth culture, with Coppola adopting the airbrushed aesthetic of the time period, including fanciful montages that mimic 1970s advertising. This creates a very real distinction between the perception of the Lisbon Sisters and their reality. Likewise, it plays into the delicate balance between drama and satire that makes The Virgin Suicides all the more special. Coppola’s script expertly skewers the overly manicured banality of suburban life. It’s given an added sharpness by her embracing of the standard model of adolescent stories: teenagers are more acutely aware of the world than the adults who make them miserable. Indeed, at the core of The Virgin Suicides is a belief that as the 20th Century wore on, things had grown more complicated and difficult to navigate for developing youth--a theory that has only gained traction in the new millennium.

Adding to this push and pull is how the girls alternate between being in control and having it taken away from them. This is the most pronounced in Dunst’s Lux, the most adventurous and also the most desired, whose actions bring the most consequences. Again, while the majority see Lux as carefree and rebellious, all sunshine and smiles, Coppola gives us glimpses of her many disappointments. The common pose of the pouty teenager smoking a cigarette gives way to a more knowing look of defeat, a replica of a much older woman, a femme fatale who has seen what beauty and seduction has gotten her. It is interesting to compare this with the role Dunst played in Coppola’s most recent picture, The Beguiled. In that movie, she plays Edwina, a teacher who is on the cusp of becoming a spinster whose embracing of her own sexuality also brings despair.

There are actually many comparisons to be drawn between The Virgin Suicides and The Beguiled. Both are stories about women who are secluded by circumstance, who have reason to fear the intrusion of men from outside and are surrounded by death. There are even parallel dinner scenes where an unsuspecting man finds himself at a table full of women, suddenly awash in a subtext of competition and desire (in one, the student Peter Sisten (Chris Hale) invited over by his teacher; in the other, Colin Farrell looking for safe haven). It’s almost as if The Beguiled is The Virgin Suicides made with a more experienced eye, even if the characters are possessed of a similar naïveté.

Speaking of that famous family, a couple of them show up on the bonus features. Brother Roman (director of CQ, regular Wes Anderson collaborator, and second-unit director on The Virgin Suicides) teams with his sister to direct the amusing music video tie-in for Air’s “Playground Love,” taken from the score. And mother Eleanor Coppola, the regular chronicler of Coppola productions (most notably, Hearts of Darkness), shot the 23-minute Making of “The Virgin Suicides,” an illuminating behind-the-scenes press kit featuring on-set footage and interviews with cast and crew, including Jeffrey Eugenides, who himself sees the difference between the director’s interest in his characters and his own. There’s a whole section on what different family members that chipped in or participated, including Robert Schwartzman playing the gangster’s son, Paul Baldino. The image portrayed is of a fun, collaborative set. Though, the opening clip of James Woods declaring his “crush” on Sofia hasn’t aged as well as the rest...

Also included is Sofia Coppola’s 1998 short Lick the Star. This black-and-white tale chronicles the fickle ins-and-outs of seventh-grade social structures, focusing on a group of girls concocting a scheme to poison high school boys, inspired by their love of Flowers in the Attic. The cool contemporary soundtrack and the script’s shifting character allegiances prefigures The Virgin Suicides. Blink and you might also miss both Robert Schwartzmen and Anthony DeSimone, who show up again in Suicides, as well as cameos by filmmakers Peter Bogdanovich and Zoe R. Cassavetes, another second-generation director with a famous father.

For fans looking for more updated special features, Criterion also provides plenty of new interviews, as well as a retrospective by Rookie-creator Tavi Gevinson, a devotee who discovered the film in her own early life (she was three when The Virgin Suicides was released).

My other Sofia Coppola reviews:

Lost in Translation

Marie Antoinette theatrical

Marie Antoinette home video

Somewhere

The Bling Ring

Saturday, August 16, 2014

REDUX: THE DARJEELING LIMITED - #540

This is my second write-up of Wes Anderson's The Darjeeling Limited. You can read my older review here. What is below isn't actually a legit review, or even a finished piece. These are my rough notes for an introduction I made last night before a screening of the movie, complete with "Hotel Chevalier," as part of the NW Film Center's "Wes's World: Wes Anderson and his Influences" festival. It features some old ideas cribbed from my previous write-up, and some new ones based on my re-watching the film. The piece is still a bit ragged, as it was just meant to act as a guide for while I talked, so there are likely some typos; each time you encounter one, imagine me saying...

The Darjeeling Limited has become the default Wes Anderson movie that no one cares about. You bring it up, everyone’s got an opinion about it.

To me, it’s one of the more interesting and challenging of his movies. It’s a eulogy for the Anderson movies that came before it, ending one phase of his career and setting the stage for the next.

As Marc Mohan said last week introducing The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou [review], the filmography of Wes Anderson is almost like one giant film, the way Susan Sontag described the 1960s work of Jean-Luc Godard. It’s all connected, and if not literally one volume to the next, it’s at least a shared universe. Thus, there are treads and characters that connect: to all of his other movies. You have Max Fischer, Richie Tenenbaum, maybe a little Eli Cash.

You have Steve Zissou, being left behind, almost like a phantom. To my way of thinking, the bit part Bill Murray plays here is actually their father, whose passing has prompted the journey the three brothers at the center of the movie are taking.

In essence, the father figure is dead. It’s time to move on in search of the next thing. This makes for one of the more emotionally raw of Anderson’s films. It wears its heart on its sleeve.

Which means it gets personal in ways Anderson movies haven’t before. There are three writers behind this: Wes Anderson, his filmmaking compatriot Roman Coppola, and actor Jason Schwartzman, who is also Roman’s cousin. Each writer has created an avatar for himself in the three brothers in the movie, and infused their mannerisms and fetishes with coded symbolism.

In fact, the whole movie, like much of Anderson’s work, has kind of a secret code that you have to break. The filmmaker is often accused of being precious, but every detail matters. He is precious in that he is like a little kid trying to build what he sees in his imagination, and he cares deeply about getting it right.

Owen Wilson plays Francis, the eldest, and he serves as a stand-in for Wes Anderson. Francis is the beleaguered ringleader, unappreciated and beaten-up--which was probably how Wes felt following the tepid reception to The Life Aquatic. Like his creator, Francis also wants to get it right. He wants to contain the chaos, but finds he can’t. You can’t manufacture a spiritual journey. He tells his brothers to “say yes to everything,” but then hands them an itinerary.

Jason Schwartzman plays Jack, and in doing so represents himself: the arty romantic looking to stake a claim.

I’m glad they are including the prologue of “Hotel Chevalier” because Darjeeling is really incomplete without it. Particularly in regards to Jack. He is essentially Max Fischer looking to be grow up and be taken seriously, stuck in a fugue at a time where the fictions he has created have become too real and have overtaken him.

Look around his hotel room, you’ll see he has essentially built himself a replica of his childhood bedroom, a la Edward Appleby, the dead romantic figure in Rushmore. [review] There are toy cars, art pieces, and objects that are important to him. He’s locked away, indulging in books and movies.

He’s watching Billy Wilder’s Stalag 17 on the TV. In that film, William Holden’s character is like the Max Fischer of the POW camps: he has the whole place wired. He built a racetrack and runs mice on them. He has a telescope for looking at the women in the neighbor camp. He is both separate and apart.

on the TV. In that film, William Holden’s character is like the Max Fischer of the POW camps: he has the whole place wired. He built a racetrack and runs mice on them. He has a telescope for looking at the women in the neighbor camp. He is both separate and apart.

You also might spot a Nancy Mitford book on his bed. It’s a twofer , one of my favorites, the combined The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate. Mitford is a bit like F. Scott Fitzgerald as a woman, known for beautiful prose and writing thinly veiled fictions about her and her sisters; Jack does the same about him and his brothers. No matter how much he claims it’s all made up.

, one of my favorites, the combined The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate. Mitford is a bit like F. Scott Fitzgerald as a woman, known for beautiful prose and writing thinly veiled fictions about her and her sisters; Jack does the same about him and his brothers. No matter how much he claims it’s all made up.

Things go wonky for Jack in his exile when that his estranged lover--played by Natalie Portman--shows up unannounced and invades his space. Bad for him, lucky for us, in that it’s easily the sexiest a Wes Anderson movie has ever gotten. But Natalie Portman also utters the first of many portents in Darjeeling: “Don’t you think it’s time you go home?” He can’t escape his past any more than he can escape her.

“Hotel Chevalier” ends with a song by Peter Sarstedt, “Where Do You Go To My Lovely,” which is the most Wes Anderson of songs. It’s all references--Marlene Dietrich, the Rolling Stones--using these superficial details to get into a lover’s head. There’s something so self-conscious about it, it’s hard not to think Anderson is toying with us. “Where Do You Go To” becomes Jack’s love theme.

Finally, we have the most complex character to decode: Roman Coppola, as represented by Adrien Brody. Peter is also trying to establish himself as his own man, and his real-life parallel maybe has the most to overcome in that regard. Roman Coppola is a film director himself, he made a movie called CQ many years back--about, surprise, a young filmmaker trying to avoid turning into a hack. His resume also includes a lot of second unit work for his famous father: Francis Ford Coppola.

Francis Coppola one of the more influential titans of the 1970s. He was surely an influence on Wes Anderson. The Conversation , the Godfather films [review], Apocalypse Now

, the Godfather films [review], Apocalypse Now .

.

Keep that in mind when you observe Adrien Brody in Darjeeling: he is the one who keeps stealing his dead father’s clothes for himself. He wears the old man’s glasses, so as a metaphor is looking through his eyes, despite it being a different prescription than his own. As the offspring of a famous man, it’s hard to establish your own vision.

This carries over into the theme of fathers. I think it’s Peter, Brody’s character, who gives the best evidence that Bill Murray is their dead dad. Watch how he looks at the Bill Murray in that first scene, both when he passes him, and once he’s on the train.

Peter is also dealing with his own issues: he could the next Royal Tenenbaum or Steve Zissou. His wife is pregnant, and he is running away. Sadly, later, he’ll be the one who fails in saving another child. Not a good omen.

The fact that Wes Anderson is trading some of his daddy issues to focus on mommy issues is kind of fascinating. Anjelica Huston as the mother in both Tenenbaums [review] and Zissou was still invested in what the men were doing, she’s the one who takes care of things, even reluctantly. Not this time. For the first time in Anderson, the mother has abandoned her post. (Not counting the late Mrs. Fischer.) Maybe in that sense the German women on the train are supposed to make us think of Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes. [review] She can’t help but get out of there, and you can’t blame her. She’s had enough.

Extending the Coppola comparison, for a second, and sticking with fathers and mothers: there is a journey here akin to Apocalypse Now. In looking for their mom, the boys are seeking the rogue who has gone native.

There is also Hearts of Darkness , the documentary about the making of that film, where we see it was Roman Coppola’s mother, Eleanor, who kept the movie--and his father--on track when Francis Ford’s mad boyish adventure went off the tracks.

, the documentary about the making of that film, where we see it was Roman Coppola’s mother, Eleanor, who kept the movie--and his father--on track when Francis Ford’s mad boyish adventure went off the tracks.

Also in Apocalypse Now, there is the threat of a tiger attack, which we have repeated here. Francis Ford Coppola himself was referencing William Blake: “Tyger Tyger, burning bright, / In the forests of the night; / What immortal hand or eye, / Could frame thy fearful symmetry?”

This maybe wasn’t intentional on Anderson’s, but if you were here for Shawn Levy’s introduction to Rushmore, these things extend back whether it’s planned or not. Shawn quoted Borges stating that artists create their own precedents, even if by osmosis or coincidence. And one of the major reasons for this series is to make these connections, we want to see how the themes all lock together.

I was struck watching this last night, actually, that the train porter serves as a kind of father figure, immediately usurping Owen Wilson’s authority the moment they step on his train. If we want to go a little silly, then that means Jack/Jason Schwartzman sleeping with the porter’s girlfriend has some Oedipal overtones. Not to mention Natalie Portman and Anjelica Huston have matching haircuts.

But that may be going to far. It’s still worth considering, thought, that Owen Wilson’s Francis might want to take over for his dad, but what we end up seeing is that he’s just like his mother. All his habits are from her. I like the line he says, “Did I raise us...kind of?” She won’t validate him, he’s hoping his brothers will.

Moving on from that...

The other important film connection to make here is to India. India provides Wes Anderson an opportunity. Where I think Darjeeling provides a bridge between the two phases of Anderson’s career is he steps outside of his own uncanny valley in away he hasn’t before. It’s his first time away from an entirely curated world.

We left the city in Steve Zissou, sure, but Zissou still lived in an imaginary landscape, one that he could control, it was his Life Aquatic.

In Darjeeling, while the characters still bear a stylistic connection to the Anderson aesthetic, they have been moved into a world that is beyond their control, where they don’t fit. While cinematically, it’s the India that the director saw in early Merchant-Ivory movies and Satyajit Ray, it still resembles something other than Anderson’s common landscape. The Darjeeling Limited both as narrative and as process is an adventure of displacement.

As I mentioned, Francis is trying to manufacture and manicure the spiritual experience, but it’s way to controlled for a legitimate epiphany. To the point that to have a real experience, the boys have to be thrown off the train and see life as it’s really being lived, away from the conveniences of privileged travel. It makes me think a little of Lost In Translation, [review] and Scarlett Johansson leaving the hotel where she’s been hiding and viewing Japanese life as an observant witness. (A film, of course, made by Roman Coppola’s extremely talented little sister.)

These guys are presented with a real awakening moment out at the river and in the remote village, but of course, they kind of miss it. Anderson makes the connection for them, he goes from one funeral back to another, letting us see the events prior to burying their father, but these guys are dense. They immediately fall back into their old tricks once they return to the city, and have no choice but to go back out again and finish what they started.

After this, we would see Anderson retreat back into his own environment, and even take it to new extremes. Moonrise Kingdom [review] and to a greater extent Grand Budapest Hotel [review] has moved him even further from reality. There is a kind of magical realism, a cinematic illusion a la Georges Méliès, that has taken over his material. It’s actually hinted at in this movie with the very obviously fake tiger. There’s a part of him that wants the illusion to appear as illusion

I don’t know if the poor reaction to Darjeeling inspired it, but there is almost a sense that Anderson decided to take his ball and go home. If we didn’t want him stepping out into a recognizable world, then he wasn’t going to. He would create his own. I imagine him sitting in his studio listening to the Beach Boys’ “In My Room” and dreaming up this new fantasy life, untethered and unrestricted. It’s what’s made his latest films so fresh, but what also makes The Darjeeling Limited so effective. As they say, you have to leave before you can come back.

The Darjeeling Limited has become the default Wes Anderson movie that no one cares about. You bring it up, everyone’s got an opinion about it.

To me, it’s one of the more interesting and challenging of his movies. It’s a eulogy for the Anderson movies that came before it, ending one phase of his career and setting the stage for the next.

As Marc Mohan said last week introducing The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou [review], the filmography of Wes Anderson is almost like one giant film, the way Susan Sontag described the 1960s work of Jean-Luc Godard. It’s all connected, and if not literally one volume to the next, it’s at least a shared universe. Thus, there are treads and characters that connect: to all of his other movies. You have Max Fischer, Richie Tenenbaum, maybe a little Eli Cash.

You have Steve Zissou, being left behind, almost like a phantom. To my way of thinking, the bit part Bill Murray plays here is actually their father, whose passing has prompted the journey the three brothers at the center of the movie are taking.

In essence, the father figure is dead. It’s time to move on in search of the next thing. This makes for one of the more emotionally raw of Anderson’s films. It wears its heart on its sleeve.

Which means it gets personal in ways Anderson movies haven’t before. There are three writers behind this: Wes Anderson, his filmmaking compatriot Roman Coppola, and actor Jason Schwartzman, who is also Roman’s cousin. Each writer has created an avatar for himself in the three brothers in the movie, and infused their mannerisms and fetishes with coded symbolism.

In fact, the whole movie, like much of Anderson’s work, has kind of a secret code that you have to break. The filmmaker is often accused of being precious, but every detail matters. He is precious in that he is like a little kid trying to build what he sees in his imagination, and he cares deeply about getting it right.

Owen Wilson plays Francis, the eldest, and he serves as a stand-in for Wes Anderson. Francis is the beleaguered ringleader, unappreciated and beaten-up--which was probably how Wes felt following the tepid reception to The Life Aquatic. Like his creator, Francis also wants to get it right. He wants to contain the chaos, but finds he can’t. You can’t manufacture a spiritual journey. He tells his brothers to “say yes to everything,” but then hands them an itinerary.

Jason Schwartzman plays Jack, and in doing so represents himself: the arty romantic looking to stake a claim.

I’m glad they are including the prologue of “Hotel Chevalier” because Darjeeling is really incomplete without it. Particularly in regards to Jack. He is essentially Max Fischer looking to be grow up and be taken seriously, stuck in a fugue at a time where the fictions he has created have become too real and have overtaken him.

Look around his hotel room, you’ll see he has essentially built himself a replica of his childhood bedroom, a la Edward Appleby, the dead romantic figure in Rushmore. [review] There are toy cars, art pieces, and objects that are important to him. He’s locked away, indulging in books and movies.

He’s watching Billy Wilder’s Stalag 17

You also might spot a Nancy Mitford book on his bed. It’s a twofer

Things go wonky for Jack in his exile when that his estranged lover--played by Natalie Portman--shows up unannounced and invades his space. Bad for him, lucky for us, in that it’s easily the sexiest a Wes Anderson movie has ever gotten. But Natalie Portman also utters the first of many portents in Darjeeling: “Don’t you think it’s time you go home?” He can’t escape his past any more than he can escape her.

“Hotel Chevalier” ends with a song by Peter Sarstedt, “Where Do You Go To My Lovely,” which is the most Wes Anderson of songs. It’s all references--Marlene Dietrich, the Rolling Stones--using these superficial details to get into a lover’s head. There’s something so self-conscious about it, it’s hard not to think Anderson is toying with us. “Where Do You Go To” becomes Jack’s love theme.

Finally, we have the most complex character to decode: Roman Coppola, as represented by Adrien Brody. Peter is also trying to establish himself as his own man, and his real-life parallel maybe has the most to overcome in that regard. Roman Coppola is a film director himself, he made a movie called CQ many years back--about, surprise, a young filmmaker trying to avoid turning into a hack. His resume also includes a lot of second unit work for his famous father: Francis Ford Coppola.

Francis Coppola one of the more influential titans of the 1970s. He was surely an influence on Wes Anderson. The Conversation

Keep that in mind when you observe Adrien Brody in Darjeeling: he is the one who keeps stealing his dead father’s clothes for himself. He wears the old man’s glasses, so as a metaphor is looking through his eyes, despite it being a different prescription than his own. As the offspring of a famous man, it’s hard to establish your own vision.

This carries over into the theme of fathers. I think it’s Peter, Brody’s character, who gives the best evidence that Bill Murray is their dead dad. Watch how he looks at the Bill Murray in that first scene, both when he passes him, and once he’s on the train.

Peter is also dealing with his own issues: he could the next Royal Tenenbaum or Steve Zissou. His wife is pregnant, and he is running away. Sadly, later, he’ll be the one who fails in saving another child. Not a good omen.

The fact that Wes Anderson is trading some of his daddy issues to focus on mommy issues is kind of fascinating. Anjelica Huston as the mother in both Tenenbaums [review] and Zissou was still invested in what the men were doing, she’s the one who takes care of things, even reluctantly. Not this time. For the first time in Anderson, the mother has abandoned her post. (Not counting the late Mrs. Fischer.) Maybe in that sense the German women on the train are supposed to make us think of Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes. [review] She can’t help but get out of there, and you can’t blame her. She’s had enough.

Extending the Coppola comparison, for a second, and sticking with fathers and mothers: there is a journey here akin to Apocalypse Now. In looking for their mom, the boys are seeking the rogue who has gone native.

There is also Hearts of Darkness

Also in Apocalypse Now, there is the threat of a tiger attack, which we have repeated here. Francis Ford Coppola himself was referencing William Blake: “Tyger Tyger, burning bright, / In the forests of the night; / What immortal hand or eye, / Could frame thy fearful symmetry?”

This maybe wasn’t intentional on Anderson’s, but if you were here for Shawn Levy’s introduction to Rushmore, these things extend back whether it’s planned or not. Shawn quoted Borges stating that artists create their own precedents, even if by osmosis or coincidence. And one of the major reasons for this series is to make these connections, we want to see how the themes all lock together.

I was struck watching this last night, actually, that the train porter serves as a kind of father figure, immediately usurping Owen Wilson’s authority the moment they step on his train. If we want to go a little silly, then that means Jack/Jason Schwartzman sleeping with the porter’s girlfriend has some Oedipal overtones. Not to mention Natalie Portman and Anjelica Huston have matching haircuts.

But that may be going to far. It’s still worth considering, thought, that Owen Wilson’s Francis might want to take over for his dad, but what we end up seeing is that he’s just like his mother. All his habits are from her. I like the line he says, “Did I raise us...kind of?” She won’t validate him, he’s hoping his brothers will.

Moving on from that...

The other important film connection to make here is to India. India provides Wes Anderson an opportunity. Where I think Darjeeling provides a bridge between the two phases of Anderson’s career is he steps outside of his own uncanny valley in away he hasn’t before. It’s his first time away from an entirely curated world.

We left the city in Steve Zissou, sure, but Zissou still lived in an imaginary landscape, one that he could control, it was his Life Aquatic.

In Darjeeling, while the characters still bear a stylistic connection to the Anderson aesthetic, they have been moved into a world that is beyond their control, where they don’t fit. While cinematically, it’s the India that the director saw in early Merchant-Ivory movies and Satyajit Ray, it still resembles something other than Anderson’s common landscape. The Darjeeling Limited both as narrative and as process is an adventure of displacement.

As I mentioned, Francis is trying to manufacture and manicure the spiritual experience, but it’s way to controlled for a legitimate epiphany. To the point that to have a real experience, the boys have to be thrown off the train and see life as it’s really being lived, away from the conveniences of privileged travel. It makes me think a little of Lost In Translation, [review] and Scarlett Johansson leaving the hotel where she’s been hiding and viewing Japanese life as an observant witness. (A film, of course, made by Roman Coppola’s extremely talented little sister.)

These guys are presented with a real awakening moment out at the river and in the remote village, but of course, they kind of miss it. Anderson makes the connection for them, he goes from one funeral back to another, letting us see the events prior to burying their father, but these guys are dense. They immediately fall back into their old tricks once they return to the city, and have no choice but to go back out again and finish what they started.

After this, we would see Anderson retreat back into his own environment, and even take it to new extremes. Moonrise Kingdom [review] and to a greater extent Grand Budapest Hotel [review] has moved him even further from reality. There is a kind of magical realism, a cinematic illusion a la Georges Méliès, that has taken over his material. It’s actually hinted at in this movie with the very obviously fake tiger. There’s a part of him that wants the illusion to appear as illusion

I don’t know if the poor reaction to Darjeeling inspired it, but there is almost a sense that Anderson decided to take his ball and go home. If we didn’t want him stepping out into a recognizable world, then he wasn’t going to. He would create his own. I imagine him sitting in his studio listening to the Beach Boys’ “In My Room” and dreaming up this new fantasy life, untethered and unrestricted. It’s what’s made his latest films so fresh, but what also makes The Darjeeling Limited so effective. As they say, you have to leave before you can come back.

Friday, July 5, 2013

THREE FILMS BY ROBERTO ROSSELLINI STARRING INGRID BERGMAN: JOURNEY TO ITALY - #675

My current frontrunner for the best movie of 2013 is Richard Linklater's Before Midnight [review], an emotionally turbulent, challenging movie about a long-tem couple who unexpectedly find themselves at a crossroads where they are questioning whether or not their relationship is worth continuing. It's a film that earns all of the feelings in engenders. Not unlike its spiritual predecessor, Roberto Rossellini's 1954 movie Journey to Italy (a.k.a. Voyage to Italy).

The director's crowning collaboration with Ingrid Bergman could serve as a sort of omen: their relationship would eventually disintegrate for good. Here, though, we find the pair perfectly in sync. Bergman plays Katherine Joyce, an upper-class wife of a British businessman. Alex (George Sanders) has recently inherited some property from his uncle, some land and a fancy home in Naples. Alex and Katherine have gone to Italy to sell it, and while they are away, do a little vacationing. Alex is a workaholic and it's hard to get him out of the office, which may explain why, now that Katherine has managed to get some alone time with him, they realize they don't know each other at all.

Ennui and jealousy make for a nasty combination. Husband and wife are bored with each other and the decades-long conversation they've been having. Yet, as is usually the case in such situations, they don't want anyone else being bored by their spouse, that is their right alone. And so it is that Alex begins to resent a dead poet whose verse has outlined Katherine's Italian itinerary. Though this kind of suspicion angers Katherine, she becomes guilty of it herself when they happen to run into a woman Alex has known previously. She is on a group vacation with some friends, and Alex pays the ladies in the traveling party extra attention when they are all out having drinks. Katherine says that she never knew that her hubby was so interested in women. Translation: why aren't you that interested in me?

After a few snippy arguments, the pair goes their separate ways to finish out the trip. Alex goes to Capri to catch up with his friend, while Katherine stays behind in Naples to continue to tour the historical spots and look at the ancient relics. She also spends her time drinking in the local color and observing the people. I was reminded a bit of Sofia Coppola's Lost in Translation [review]. Ingrid Bergman wandering about and soaking up the culture has echoes in how Scarlett Johansson spies on ceremonies and customs in Japan while her husband is off pursuing actresses; likewise, George Sanders is gruff and sarcastic, and while not as loveable as Bill Murray, his flirtations with familiar ladies in foreign lands is not that different than Bob Harris.

Perhaps it's because he loved her that Rossellini tips the scales a little in Ingrid Bergman's favor in this film. Katherine is given an internal monologue that, despite its vitriol, humanizes her to a greater degree than Alex. Couple that with her more demonstrable abilities to empathize with her fellow man, and she seems far less beastly than her husband. Alex's self-recrimination is born of failure and rejection, and the standards he nearly sacrifices to try to reclaim some of his wild oats are troubling--even to him. “Beastly” may not be the right word, actually. Alex is less likable, but he's no less human. Sanders is also an actor on par with Bergman, and despite the clash of wills, both performers manage to make the Joyces seem like a real couple. Despite their differences, despite the spite, they fit. It's evident anytime they are in the car, but particularly in their penultimate conversation, when it appears they will call it quits. (Again, automobiles make for a regular staging ground for arguments. The Before Midnight disagreement begins in a car, also while the couple are on vacation; and let's not forget the hot-tempered, cold-blooded exchanges between Audrey Hepburn and Albert Finney in Stanley Donen's exceptional Two for the Road .)

.)

As a conclusion to this cycle of films, the trio of Ingrid Bergman vehicles sometimes known as “The Solitude Trilogy,” Rossellini brings it all back around to Stromboli [review]. He does so aesthetically by his incorporation of real locations and real people to the drama, and how her new surroundings affect his leading lady. He also connects it back to their initial collaboration in how he handles the ending. The fate of the Joyces' conjugal union is decided by a religious epiphany, by a miracle--though in this case, not one that happens to Ingrid Bergman. Rather, it happens in her vicinity and threatens to swallow her. It is a human volcano, rather than the literal one in Stromboli; the people who move against her confirm her truth by trying to sweep her away a la Europe '51 [review]. There's a directness to how the director handles it in Journey to Italy that makes it more powerful than the endings of its predecessors. In Journey, the actions of the characters take over, and there is no need for further explanation. The intense feelings that power their decisions speak for themselves.

Monday, July 1, 2013

SIDELINE: MORE REVIEWS FOR 6/13

While I was neglecting this site, I was still watching a lot of movies. Here's proof.

Oh, and I was also redesigning my other site! Have a look. See what I'm working on. Buy some signed books. confessions123.com

IN THEATRES...

My Oregonian columns...

* June 14: French animation gets arty in The Painting; Disney's Pete's Dragon flies back to the big screen; and a life re-examined in Long Distance Revolutionary: A Journey with Mumia Abu-Jamal.

* June 21: Another visit with Andre Gregory in Before and After Dinner, the nuclear power doc Pandora's Promise, and a sleazy Italian slasher flick from 1973, Torso.

* June 28: the dark Australian comedy 100 Bloody Acres; Doin' it in the Park's wild history of NYC pick-up basketball; and a revival of the classic Grant/Hepburn crime/romance hybrid Charade.

ON BD/DVD....

Oh, and I was also redesigning my other site! Have a look. See what I'm working on. Buy some signed books. confessions123.com

IN THEATRES...

* Before Midnight, the latest in the ongoing relationship series is its deepest and most emotionally fraught, and quite easily the best. Once again starring Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy, directed by Richard Linklater.

* The Bling Ring, the latest from Sofia Coppola, telling a tale of disaffected Bonnies and their tagalong Clyde.

* Byzantium, Neil Jordan's all-too-serious return to the vampire genre.

* Dirty Wars, a documentary about the covert strikes happening outside the approved combat zones in the War on Teror.

* Man of Steel, is neither worth loving or hating. It's boring and fun and long and loud and dazzling and doltish all at the same time.

* Monsters University, a Pixar prequel that's funny, if not as fresh as the original.

* Much Ado About Nothing, Joss Whedon's backyard retelling of the Bard.

* Some Girl(s), starring Adam Brody as a writer lacking in self-awareness taking a tour of his old flames. From a script by Neil LaBute.

* June 14: French animation gets arty in The Painting; Disney's Pete's Dragon flies back to the big screen; and a life re-examined in Long Distance Revolutionary: A Journey with Mumia Abu-Jamal.

ON BD/DVD....

* Broadway Musicals: A Jewish Legacy, documenting the history of the great Jewish songwriters of the American stage.

* First Family, a tepid 1980 White House satire from writer/director Buck Henry and star Bob Newhart that lacks any political bite.

* Free Radicals: A History of Experimental Film, a worthy introduction to the more abstract side of cinema.

* The Great Gatsby: Midnight in Manhattan, a short BBC documentary about F. Scott Fitzgerald and his best-known novel. Bonus: a 1975 teleplay with David Hemmings as the author.

* Happy People: A Year in the Taiga, Werner Herzog's refashioning of a longer documentary looking at the life of fur trappers in Siberia.

* The Key, a dark wartime drama from Carol Reed. With William Holden and Sophia Loren.

* A Night to Remember, a screwball mystery with Loretta Young, released in 1942.

* Second-Hand Hearts, a romantic flop that kicked off the '80s for Hal Ashby.

* Whoopee! A good-time musical with Eddie Cantor. Two-strip Technicolar from 1930!

Labels:

carol reed,

documentary,

hal ashby,

herzog,

linklater,

malle,

other reviews,

shakespeare,

Sofia Coppola

Thursday, January 13, 2011

KAGEMUSHA - #267

[Note: This is the longer companion to a short review of Kagemusha I wrote for the Portland Mercury. Look for it in this week's edition, or read it on their blog here.]

Kagemusha is not a young man's film. Released in 1980, it was made when Akira Kurosawa was 70. In the previous 15 years, he had only made two movies--the misunderstood Dodes'ka-den [review] and the Russian-financed Dersu Uzala . Kagemusha was financed in part by a deal with Suntory whiskey and American funding finagled by producers Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas (there are worse ways to throw you weight around than convincing 20th Century Fox to give Akira Kurosawa some money). The Japanese legend had been in a kind of director's jail, and it's hard to say if the time away gave him a new perspective or if this is where he would end up all along. Because Kagemusha is a complex movie, one that is far less cavalier about swordplay and violence than its more famous predecessors.

. Kagemusha was financed in part by a deal with Suntory whiskey and American funding finagled by producers Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas (there are worse ways to throw you weight around than convincing 20th Century Fox to give Akira Kurosawa some money). The Japanese legend had been in a kind of director's jail, and it's hard to say if the time away gave him a new perspective or if this is where he would end up all along. Because Kagemusha is a complex movie, one that is far less cavalier about swordplay and violence than its more famous predecessors.

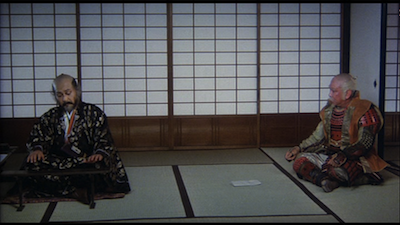

Set in the 16th Century during a time of civil war, Kagemusha is based on real events, but it is also its own fanciful thing. The title translates as "Shadow Warrior," and the script by Kurosawa and Masato Ide is an old man's version of the "Prince and the Pauper" fable. Japanese cinema mainstay Tatsuya Nakadai--he was Mifune's rival in Sanjuro [review] and Yojimbo [review], and also starred in movies like When a Woman Ascends the Stairs [review] and The Human Condition [review]--stars as Shingen Takeda, a warlord with a tenuous hold on Kyoto. He has been fending off two rivals, Nobunaga Oda (Daisuke Ryû) and Ieyasu Tokugawa (Masayuki Yui), both of whom would crush Shingen and take over Japan if given half the chance.

Nakadai also stars in the picture as his own double. At the start of Kagemusha, Shingen's brother Nobukado (Tsutomu Yamazaki) has brought him a thief who was due to be executed. The condemned criminal bears a startling resemblance to the ruler, and Nobukado believes he can prove useful as a decoy to fool his brother's enemies. The thief appears to be an unruly creature--his first order of business is asking why he's the one condemned to die when Shingen has stolen from and killed thousands in the name of "politics"--but his honesty also impresses his benefactor. They decide to keep him around.

Shortly after, Shingen is fatally shot. Before he dies, he informs his cabinet that they should hide his passing for three years while they secure their position against the others. Suddenly, the impostor is put in the seat of power for real. He's reluctant at first. Why should he give up his life for a society that rejected him? He eventually relents, deciding he should honor Shingen for sparing his life and actually stand for something. Slowly, he embraces the role of ruler, going from nervous puppet to self-deluded commander--a move that ultimately causes him to be knocked low by his own hubris. With the three years up, Shingen's former compatriots have no more need for the fake warlord, and they send the thief packing.

But who is the man now that he has given himself to be someone else's shadow? He had found a life in the palace walls, including bonding for real with Shingen's grandson--a relationship that didn't exist when the real Shingen was alive. The child almost blew the whole scheme, having sensed at once that this was not his grandfather. What tipped him off? The fact that the big man no longer scared him. It seems there was some truth to the crook's assertion that he was the better man than the more vaunted warrior.

It's a heartbreaking changeover, though. The shadow accepted his duty without any promise of reward. In shedding his self, he also shed his selfish concerns. Thus, when he is cast out by the people he served--the soldiers he once commanded throw rocks at him to drive him from the compound--he has nowhere to go, no one to be. Ironic, then, when he returns to watch "himself" be buried. When the final clash between the competing armies happens, he spies on the action from the weeds, a peeping tom on the field of battle rather than the powerful presence he had been in the last skirmish. That prior battle was also the point when he lost his way, he started to think he really was the person that the rest of them were scared of. Tatsuya Nakadai is remarkable. He is funny and warm to begin with, but then devastatingly hollow. In some ways, this feels like a dry run for his turn as Lord Ichimonji in Ran [review] five years later, but it's also its own thing. Ichimonji loses himself to madness in order to block out the horrors of the world crumbling around him, whereas the double is all too clear on how everything is going wrong.

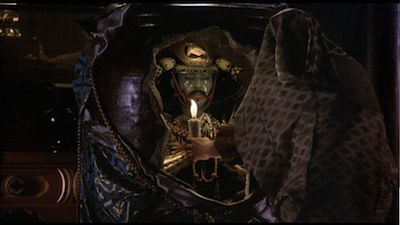

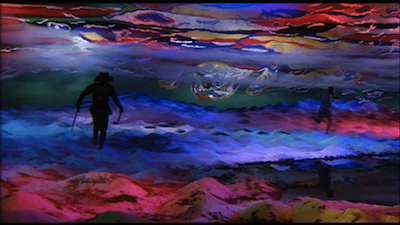

Akira Kurosawa constructed Kagemusha with a formalistic rigidity, which he then tears into with occasional explosions of color and surprising symbolism. In a gaudy dream sequence, the double is chased by his original on a painted background that looks like it was created by Van Gogh during a fit of color blindness. The epically staged war sequences are shot with an expressionistic design, abstracting them in a way that makes them beautiful and yet somehow all the more horrifying. When the pretty smoke clears, and Kurosawa shows us the carnage that lay just underneath, it's sickening to realize the excitement we, as viewers, allowed ourselves to feel. Perhaps knowing we might be immune to fake blood and dead soldiers, Kurosawa mostly focuses on the felled horses, some clinging to life, some fighting to get themselves out of the butchery all around them. This is man's cruelty: we just don't lay waste to ourselves, but to everything around us. The aftermath of the showdown looks like Hell on Earth. Life as we know it is gone.

That's when the thief comes stumbling out of the weeds. In this surreality, he is the only one left to mourn mankind and its folly. This should have been his victory, or even his failure. Instead, he has been removed. His only choice is to charge ahead, a futile final stand. The symbolism of the final shots is staggering: glory has been drowned, and its remnants wash away on a grotesque red tide.

This is the second time I have seen Kagemusha. The first time was when the DVD came out, and this time, it was on a movie screen. I don't think the difference in viewing experiences is why I rate it higher than I did prior. On my first viewing, I liked it fine, but it didn't strike me as heavy as it did the second time. That's possibly because there is a lot to keep straight in this movie. The political intrigue that fuels not just the civil war, but that also orchestrates the whole doppelganger scheme, can get pretty complicated. There are so many characters, it's kind of one of those "you can't tell the players without a program" situations. (Thankfully, Kurosawa helpfully introduces each character with a caption as they appear.) On the first time through, it can be hard to separate that part of the story from the richer personal drama, something I was able to do when giving it another look.

That said, the 35mm print I was lucky enough to watch this time around was marvelous. Any scratches or spots were few and far between, and the rich colors and dynamic sound were a pleasure to partake. Kagemusha is a film writ large to begin with, so actually seeing it in the large theatrical format is a real treat. I am not sure how extensively this print is currently touring the country, but Portland's fantastic independent theatre Cinema 21 has it for four days, January 14 to the 17th. This is the same place that gave us a big-screen Ran only a few months ago. I suppose it would be too much to ask that you guys keep working backward through the Kurosawa filmography? I'd love to come out and see Dersu Uzala in a couple of months if you do!

One final note: Those Suntory commercials, which were actually directed by Francis Ford Coppola, are included on the DVD, alongside a short documentary about Kurosawa's connection to the American filmmakers who helped him out. These commercials would later go on to inspire Sofia Coppola to use Suntory whiskey spots as the reason Bob Campbell (Bill Murray) goes to Tokyo in Lost in Translation [review].

Kagemusha is not a young man's film. Released in 1980, it was made when Akira Kurosawa was 70. In the previous 15 years, he had only made two movies--the misunderstood Dodes'ka-den [review] and the Russian-financed Dersu Uzala

Set in the 16th Century during a time of civil war, Kagemusha is based on real events, but it is also its own fanciful thing. The title translates as "Shadow Warrior," and the script by Kurosawa and Masato Ide is an old man's version of the "Prince and the Pauper" fable. Japanese cinema mainstay Tatsuya Nakadai--he was Mifune's rival in Sanjuro [review] and Yojimbo [review], and also starred in movies like When a Woman Ascends the Stairs [review] and The Human Condition [review]--stars as Shingen Takeda, a warlord with a tenuous hold on Kyoto. He has been fending off two rivals, Nobunaga Oda (Daisuke Ryû) and Ieyasu Tokugawa (Masayuki Yui), both of whom would crush Shingen and take over Japan if given half the chance.

Nakadai also stars in the picture as his own double. At the start of Kagemusha, Shingen's brother Nobukado (Tsutomu Yamazaki) has brought him a thief who was due to be executed. The condemned criminal bears a startling resemblance to the ruler, and Nobukado believes he can prove useful as a decoy to fool his brother's enemies. The thief appears to be an unruly creature--his first order of business is asking why he's the one condemned to die when Shingen has stolen from and killed thousands in the name of "politics"--but his honesty also impresses his benefactor. They decide to keep him around.

Shortly after, Shingen is fatally shot. Before he dies, he informs his cabinet that they should hide his passing for three years while they secure their position against the others. Suddenly, the impostor is put in the seat of power for real. He's reluctant at first. Why should he give up his life for a society that rejected him? He eventually relents, deciding he should honor Shingen for sparing his life and actually stand for something. Slowly, he embraces the role of ruler, going from nervous puppet to self-deluded commander--a move that ultimately causes him to be knocked low by his own hubris. With the three years up, Shingen's former compatriots have no more need for the fake warlord, and they send the thief packing.

But who is the man now that he has given himself to be someone else's shadow? He had found a life in the palace walls, including bonding for real with Shingen's grandson--a relationship that didn't exist when the real Shingen was alive. The child almost blew the whole scheme, having sensed at once that this was not his grandfather. What tipped him off? The fact that the big man no longer scared him. It seems there was some truth to the crook's assertion that he was the better man than the more vaunted warrior.

It's a heartbreaking changeover, though. The shadow accepted his duty without any promise of reward. In shedding his self, he also shed his selfish concerns. Thus, when he is cast out by the people he served--the soldiers he once commanded throw rocks at him to drive him from the compound--he has nowhere to go, no one to be. Ironic, then, when he returns to watch "himself" be buried. When the final clash between the competing armies happens, he spies on the action from the weeds, a peeping tom on the field of battle rather than the powerful presence he had been in the last skirmish. That prior battle was also the point when he lost his way, he started to think he really was the person that the rest of them were scared of. Tatsuya Nakadai is remarkable. He is funny and warm to begin with, but then devastatingly hollow. In some ways, this feels like a dry run for his turn as Lord Ichimonji in Ran [review] five years later, but it's also its own thing. Ichimonji loses himself to madness in order to block out the horrors of the world crumbling around him, whereas the double is all too clear on how everything is going wrong.

Akira Kurosawa constructed Kagemusha with a formalistic rigidity, which he then tears into with occasional explosions of color and surprising symbolism. In a gaudy dream sequence, the double is chased by his original on a painted background that looks like it was created by Van Gogh during a fit of color blindness. The epically staged war sequences are shot with an expressionistic design, abstracting them in a way that makes them beautiful and yet somehow all the more horrifying. When the pretty smoke clears, and Kurosawa shows us the carnage that lay just underneath, it's sickening to realize the excitement we, as viewers, allowed ourselves to feel. Perhaps knowing we might be immune to fake blood and dead soldiers, Kurosawa mostly focuses on the felled horses, some clinging to life, some fighting to get themselves out of the butchery all around them. This is man's cruelty: we just don't lay waste to ourselves, but to everything around us. The aftermath of the showdown looks like Hell on Earth. Life as we know it is gone.

That's when the thief comes stumbling out of the weeds. In this surreality, he is the only one left to mourn mankind and its folly. This should have been his victory, or even his failure. Instead, he has been removed. His only choice is to charge ahead, a futile final stand. The symbolism of the final shots is staggering: glory has been drowned, and its remnants wash away on a grotesque red tide.

This is the second time I have seen Kagemusha. The first time was when the DVD came out, and this time, it was on a movie screen. I don't think the difference in viewing experiences is why I rate it higher than I did prior. On my first viewing, I liked it fine, but it didn't strike me as heavy as it did the second time. That's possibly because there is a lot to keep straight in this movie. The political intrigue that fuels not just the civil war, but that also orchestrates the whole doppelganger scheme, can get pretty complicated. There are so many characters, it's kind of one of those "you can't tell the players without a program" situations. (Thankfully, Kurosawa helpfully introduces each character with a caption as they appear.) On the first time through, it can be hard to separate that part of the story from the richer personal drama, something I was able to do when giving it another look.

That said, the 35mm print I was lucky enough to watch this time around was marvelous. Any scratches or spots were few and far between, and the rich colors and dynamic sound were a pleasure to partake. Kagemusha is a film writ large to begin with, so actually seeing it in the large theatrical format is a real treat. I am not sure how extensively this print is currently touring the country, but Portland's fantastic independent theatre Cinema 21 has it for four days, January 14 to the 17th. This is the same place that gave us a big-screen Ran only a few months ago. I suppose it would be too much to ask that you guys keep working backward through the Kurosawa filmography? I'd love to come out and see Dersu Uzala in a couple of months if you do!

One final note: Those Suntory commercials, which were actually directed by Francis Ford Coppola, are included on the DVD, alongside a short documentary about Kurosawa's connection to the American filmmakers who helped him out. These commercials would later go on to inspire Sofia Coppola to use Suntory whiskey spots as the reason Bob Campbell (Bill Murray) goes to Tokyo in Lost in Translation [review].

Labels:

francis ford coppola,

kurosawa,

Sofia Coppola

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)