In the middle of watching Akira Kurosawa's 1971 feature film Dodes'ka-den, I had to stop the movie and go out and run some errands. As I did, I caught myself more than once repeating the title in my head in much the same way the film's connecting character, Rokuchan (Yoshitaka Zushi), did in the movie. Rokuchan is known by the cruel nickname "Trolley Freak" because the mentally challenged boy spends his days driving imaginary streetcars through the slum where he lives. "Dodes'ka-den" [doh-dess-kah-den] is the sound the train's wheels make on the tracks, and he chants it over and over whenever his pretend vehicle is in motion.

For me, that kind of speaks to the experience of participating in the cinematic experiment of Dodes'ka-den: you either accept the fantasy or you do not. If you do, you're fully in it; if you don't, the film is likely to confuse, irritate, and even bore you. As Kurosawa's first color feature and the film often cited for his creative exile and slower output in the latter decades of his life, Dodes'ka-den is one of those films many cinephiles are aware of but fewer have seen. It is hotly debated amongst those who have viewed it, sometimes called a minor fugue from the Kurosawa symphony, other times called the lost masterpiece. I had personally only seen clips of it, and usually just scenes of Rokuchan chugging along. I know one documentary or another on Kurosawa's career used Rokuchan's personal fantasy as a symbol of Kurosawa's artistic stubbornness, and that seems wholly fair. I am sure the great director would see the irony that years later some viewers of Dodes'ka-den would think that he himself played the painter who accidentally sets up his easel on Rokuchan's imaginary track, is forced out of the way, and then scolded about his stupidity*. It's like his own creation was trying to tell him something--or maybe the philistines and naysayers had somehow invaded his subconscious.

Dodes'ka-den is a difficult film to describe succinctly. It's an episodic picture, a series of interlocking vignettes set in a Japanese slum. It quite literally looks like a village built in the middle of a garbage dump, and in some cases, the domiciles appear to have been put together out of material found in the refuse. One beggar (Noboru Mitani) and his son (Hiroyuki Kawase) actually live in an abandoned car, while the dilapidated huts that make up the town appear as a hodge-podge. One man's house looks like scrap metal melted together, while the homes of a pair of workers and their wives are painted in blocks of primary colors. Kurosawa also matches their clothes to their houses: the couple in the yellow house wear yellow, the couple in the red house wear red. In this, Kurosawa uses his debut outing with color film to his fullest advantage, using a stylized palette and, in the case of the beggars, exaggerated stage make-up, to add a little surreality to the bleak reality he is portraying. This impoverished village is both part of reality and separate from it, and its citizens live with both the squalidness of their existence and the dreams that transport them away from their misery.

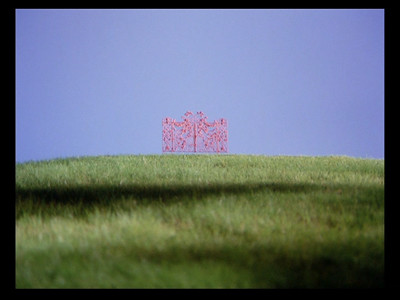

This makes Rokuchan the signalman for fantasy and possibility, his invisible train linking his neighbors to the better lives they dream of. Kind of like how a train serves as the link between Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood to the Neighborhood of Make Believe on the old Mr. Rogers TV show. If Rokuchan could keep at it through the good and the bad, there was no giving in. In a similar fashion, the most downtrodden of the locals, the beggar and his child, keep an elaborate ongoing fantasy running where the father designs the house that he will someday take his child to. It's probably telling, though, that he starts building this house with the gate, keeping the barrier between the imaginary and the real intact.

The beggar man's fence is one indication that the people in Dodes'ka-den are always trying to keep the harshness of reality at bay. Being poor usually means soldiering on even when the wolf is at the door, so this would make sense. The local kids throw rocks at Rokuchan and call him names, which he steadfastly ignores, and his mother (Kin Sugai) regularly washes away the graffiti drawings of "the Trolley Freak" before her son can see them. There are also several who constantly drink, such as the red and yellow men (Kunie Tanaka and Hisashi Igawa) and the lecherous Kyota (Tatsuo Matsumura), who forces his niece (Tomoko Yamakazi) to work while he guzzles sake. Linked to this are several instances where some people attempt to trade places, a kind of metaphorical change of station. The color-coordinated couples swap spouses for a time, and the old man of the community, Mr. Tanba (Atsushi Watanabe), calms down a rampaging drunk with a samurai sword by suggesting they switch places for a while, let him carry the burden of the blade.

Mr. Tanba is one of the more fascinating characters in the story. He could represent many things. He is an artisan running his own engraving business from his home, and he reacts to everything with a Zen calm. He is also benevolent toward his neighbors. When a thief (Sanji Kojima) breaks into his home in the middle of the night, he directs the robber to where he keeps the money and promises to have more next time. When the beggar's son grows sick, Tanba offers to take him to a doctor. Another sequence plays almost like a parable. An old man (Kamatari Fujiwara) gripped in despair tells Mr. Tanba he would rather be dead than go on living, and Tanba supplies him with a fake poison, tricking him into realizing he'd rather stay alive. Is Mr. Tanba a kind of god living amongst his creations?

The various fantasies eventually give way to harsh realities. I guess those imaginary fences aren't as protective as one would think. It's actually interesting to note that when things start to go wrong for the various characters, we don't see Rokuchan for a while, almost like his absence is the key to the change. There is also a suggestion that staying in a fantasy world and not heeding reality when it's required could lead to one's misfortune. The beggar's son grows ill when his father decides not to boil some fish before they eat it, even though the sushi chef told the boy to cook it when he gave it to him. Likewise, the beggar ignores Mr. Tanba's urging to take the child to the doctor. Then there is also the unbendable Mr. Hei (Hiroshi Akutagawa), who is so troubled by his past that he can't get out of the loop of memory and move forward. He's the only man in the dump with a lock on his door.

Yet, there is also a message that being steadfast in one's sense of personal belief and honor will get people through their travails. For instance, the lazy Kyota does not stay true to what is right, and he ends up having to pay a price, whereas Mr. Shima (Junzaburo Ben), an office worker with a severe nervous tic, stands by his wife (Yuko Kusunoki) because she has always been loyal to him, and they get through their struggles. Also on the side of the resolute, the ever-patient Ryo (Shinsuke Minami) cares for his wife's many children, ignoring rumors that not all of them, if any, are actually his. As he says, he believes he is their father, he loves them as such, so what does any further talk matter? Fantasy has its upside and it also has its downside, but life must be taken care of, as well.

In this way, of course, Rokuchan remains. He begins Dodes'ka-den, and he closes the movie, as well. His fantasy is one of duty, of having greater responsibility, and of constant motion. He may be stuck on his track, but that's no reason to sit still. Similarly, Kurosawa was in an industry that no longer wanted him, but he never stopped creating new visions. At one point, Kurosawa was even going to have all the paintings of trollies in Rokuchan's home be his own handiwork, but he realized that his art style was too mature, it didn't fit the fantasy, and for the better of the movie, he let reality encroach just a little bit.

Perhaps a smidgen more reality would make Dodes'ka-den go down easier for those who find its charms difficult to ascertain. Kurosawa needed to boil his own fish, as it were. There are hints of that other Japanese master, Ozu, in some of the stories and the overall tone of the film, but the end result is more like a "Fractured Fairy Tale" version of Ozu, his suburban families having fallen on hard times and congregated to this one location. Even so, Ozu is Ozu and Kurosawa is Kurosawa, and the former would never have allowed the quirks through, but without the quirks, Dodes'ka-den would not have anything near the curious status that it has now--and that would be a very bad thing. Akira Kurosawa had already proven what he could do with more conventional narratives, and this more complicated endeavor was the precursor to his final handful of films, which were at once more personal and more epic. Somewhere along Rokuchan's pantomimed trolley tracks, there was probably a switch that diverted his route from the expected destination to something more adventurous or even more dangerous. Dodes'ka-den was that switch for Kurosawa, a detour through a neighborhood like no other.

* The IMDB trivia page for Dodes'ka-den says that the painter is Kurosawa in an uncredited cameo, but I have found nothing to back that up. To my eye, that is not the director, and beyond that, the credits include a listing for Kazuo Kato as "the painter."

No comments:

Post a Comment