Kagemusha is not a young man's film. Released in 1980, it was made when Akira Kurosawa was 70. In the previous 15 years, he had only made two movies--the misunderstood Dodes'ka-den [review] and the Russian-financed Dersu Uzala

Set in the 16th Century during a time of civil war, Kagemusha is based on real events, but it is also its own fanciful thing. The title translates as "Shadow Warrior," and the script by Kurosawa and Masato Ide is an old man's version of the "Prince and the Pauper" fable. Japanese cinema mainstay Tatsuya Nakadai--he was Mifune's rival in Sanjuro [review] and Yojimbo [review], and also starred in movies like When a Woman Ascends the Stairs [review] and The Human Condition [review]--stars as Shingen Takeda, a warlord with a tenuous hold on Kyoto. He has been fending off two rivals, Nobunaga Oda (Daisuke Ryû) and Ieyasu Tokugawa (Masayuki Yui), both of whom would crush Shingen and take over Japan if given half the chance.

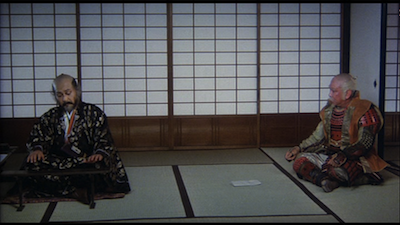

Nakadai also stars in the picture as his own double. At the start of Kagemusha, Shingen's brother Nobukado (Tsutomu Yamazaki) has brought him a thief who was due to be executed. The condemned criminal bears a startling resemblance to the ruler, and Nobukado believes he can prove useful as a decoy to fool his brother's enemies. The thief appears to be an unruly creature--his first order of business is asking why he's the one condemned to die when Shingen has stolen from and killed thousands in the name of "politics"--but his honesty also impresses his benefactor. They decide to keep him around.

Shortly after, Shingen is fatally shot. Before he dies, he informs his cabinet that they should hide his passing for three years while they secure their position against the others. Suddenly, the impostor is put in the seat of power for real. He's reluctant at first. Why should he give up his life for a society that rejected him? He eventually relents, deciding he should honor Shingen for sparing his life and actually stand for something. Slowly, he embraces the role of ruler, going from nervous puppet to self-deluded commander--a move that ultimately causes him to be knocked low by his own hubris. With the three years up, Shingen's former compatriots have no more need for the fake warlord, and they send the thief packing.

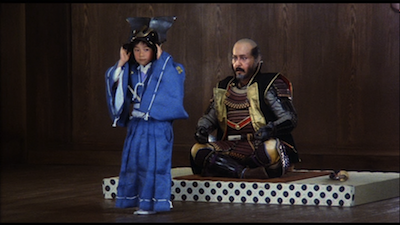

But who is the man now that he has given himself to be someone else's shadow? He had found a life in the palace walls, including bonding for real with Shingen's grandson--a relationship that didn't exist when the real Shingen was alive. The child almost blew the whole scheme, having sensed at once that this was not his grandfather. What tipped him off? The fact that the big man no longer scared him. It seems there was some truth to the crook's assertion that he was the better man than the more vaunted warrior.

It's a heartbreaking changeover, though. The shadow accepted his duty without any promise of reward. In shedding his self, he also shed his selfish concerns. Thus, when he is cast out by the people he served--the soldiers he once commanded throw rocks at him to drive him from the compound--he has nowhere to go, no one to be. Ironic, then, when he returns to watch "himself" be buried. When the final clash between the competing armies happens, he spies on the action from the weeds, a peeping tom on the field of battle rather than the powerful presence he had been in the last skirmish. That prior battle was also the point when he lost his way, he started to think he really was the person that the rest of them were scared of. Tatsuya Nakadai is remarkable. He is funny and warm to begin with, but then devastatingly hollow. In some ways, this feels like a dry run for his turn as Lord Ichimonji in Ran [review] five years later, but it's also its own thing. Ichimonji loses himself to madness in order to block out the horrors of the world crumbling around him, whereas the double is all too clear on how everything is going wrong.

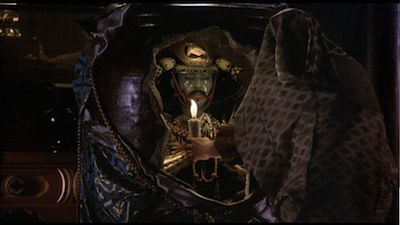

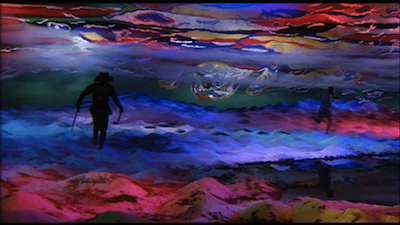

Akira Kurosawa constructed Kagemusha with a formalistic rigidity, which he then tears into with occasional explosions of color and surprising symbolism. In a gaudy dream sequence, the double is chased by his original on a painted background that looks like it was created by Van Gogh during a fit of color blindness. The epically staged war sequences are shot with an expressionistic design, abstracting them in a way that makes them beautiful and yet somehow all the more horrifying. When the pretty smoke clears, and Kurosawa shows us the carnage that lay just underneath, it's sickening to realize the excitement we, as viewers, allowed ourselves to feel. Perhaps knowing we might be immune to fake blood and dead soldiers, Kurosawa mostly focuses on the felled horses, some clinging to life, some fighting to get themselves out of the butchery all around them. This is man's cruelty: we just don't lay waste to ourselves, but to everything around us. The aftermath of the showdown looks like Hell on Earth. Life as we know it is gone.

That's when the thief comes stumbling out of the weeds. In this surreality, he is the only one left to mourn mankind and its folly. This should have been his victory, or even his failure. Instead, he has been removed. His only choice is to charge ahead, a futile final stand. The symbolism of the final shots is staggering: glory has been drowned, and its remnants wash away on a grotesque red tide.

This is the second time I have seen Kagemusha. The first time was when the DVD came out, and this time, it was on a movie screen. I don't think the difference in viewing experiences is why I rate it higher than I did prior. On my first viewing, I liked it fine, but it didn't strike me as heavy as it did the second time. That's possibly because there is a lot to keep straight in this movie. The political intrigue that fuels not just the civil war, but that also orchestrates the whole doppelganger scheme, can get pretty complicated. There are so many characters, it's kind of one of those "you can't tell the players without a program" situations. (Thankfully, Kurosawa helpfully introduces each character with a caption as they appear.) On the first time through, it can be hard to separate that part of the story from the richer personal drama, something I was able to do when giving it another look.

That said, the 35mm print I was lucky enough to watch this time around was marvelous. Any scratches or spots were few and far between, and the rich colors and dynamic sound were a pleasure to partake. Kagemusha is a film writ large to begin with, so actually seeing it in the large theatrical format is a real treat. I am not sure how extensively this print is currently touring the country, but Portland's fantastic independent theatre Cinema 21 has it for four days, January 14 to the 17th. This is the same place that gave us a big-screen Ran only a few months ago. I suppose it would be too much to ask that you guys keep working backward through the Kurosawa filmography? I'd love to come out and see Dersu Uzala in a couple of months if you do!

One final note: Those Suntory commercials, which were actually directed by Francis Ford Coppola, are included on the DVD, alongside a short documentary about Kurosawa's connection to the American filmmakers who helped him out. These commercials would later go on to inspire Sofia Coppola to use Suntory whiskey spots as the reason Bob Campbell (Bill Murray) goes to Tokyo in Lost in Translation [review].

No comments:

Post a Comment