The news went around on Monday that beloved Japanese actress Hideko Takamine had died, having lived a full life. She was 86. Takamine appeared in a staggering number of movies--177, according to IMDB. Her first was in 1929, her last in 1979. I'll admit, I haven't seen most of them. My hat is off to anyone who has. I think I've only seen the ones released by Criterion, with the most memorable for me being Keisuke Kinoshita's Twenty-Four Eyes [review]. In that film, Takamine played a young schoolteacher whose modern ways clashed with the small-town values of the village where she was assigned a school house, and who struggles to take care of the children in her care. It's a performance that is full of heart. Children are supposed to fall in love with their teachers, and as viewers, we fall in love with Takamine.

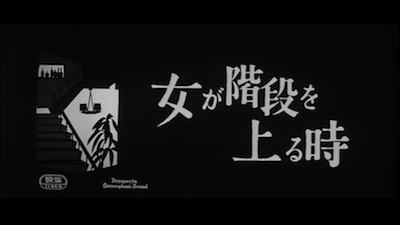

Hideko Takamine made quite a few movies with Mikio Naruse, including one of his most famous, the 1960 drama When A Woman Ascends the Stairs. As the only film in my library starring Takamine that I hadn't seen, it seemed appropriate to give it a look in honor of the actress' passing. When A Woman Ascends the Stairs is a sad film, though one that is never overly dramatic--even if some of its plot twists are straight soap opera. It also doesn't wallow. Takamine lends her character a plucky spirit that somehow spins all the bad events into a hopeful tapestry celebrating human resilience. The bar hostess Mama Keiko is a long way from the schoolteacher Hisako Oishi is terms of profession, but not in personality or allure. They are almost the same woman, especially as Oishi has seen a few things by the end of Twenty-Four Eyes. Both know heartbreak, but both have the strength to take care of themselves.

When A Woman Ascends the Stairs is set in the Ginza district, a post-War neighborhood where businessmen congregated to drink and carouse. There, the streets were lined with bars that featured women on staff as "hostesses." Their job was to entertain the customers and encourage them to buy drinks. Some extended their duties to after hours, either selling themselves one night at a time or becoming full-time mistresses.

As far as Keiko is concerned, that extra-curricular "duty" is for the lower-class hostesses. There are three tiers, as she describes it: the bottom resort to going home with clients, the middle take a train home, and the best hostesses can afford a cab. Or at least pretend they can afford it. It's common for women like Keiko to live beyond their means so as to foster the illusion that they are expensive prizes. Keiko's apartment is luxurious for a widow, but it goes with the profession. Her husband was hit by a truck not long after they were married, leaving his young bride to fend for herself. Keiko has been a hostess for five years, having been recruited by Komatsu (Tatsuya Nakadai, who also co-starred with Takamine in The Human Condition [review]) when she was a cashier. Komatsu is still her manager, taking care of accounts at the bar where Keiko oversees the other girls. Her position is why everyone calls her "Mama," including her clients, most of whom want to drink with a pretty woman and tell her about their day.

A pretty woman other than their wives, that is. Most of them are married, and most of them are in love with Keiko, though she knows they will never leave their families to give her the life she deserves. That is part of why she stays out of their reach, though one suspects from the get-go that she has more romantic tendencies than she lets on. Komatsu is in love with her, too, but he is either incapable or inept when it comes to showing it. Keiko really loves the banker Fujisaki (Masayuki Mori), one of the only men in her clientele who hasn't tried too hard to push her into something more (we see her refuse out-of-town trips, start-up money for her own bar, and even lunch dates). Not that he's really that good of a guy. I mean, Jesus, he's a banker!

All of this works for Keiko, but it doesn't make her happy. The title When A Woman Ascends the Stairs refers to her nightly journey upstairs to the bar. It's a climb she dreads. She knows this occupation is beneath her, and she doesn't even like alcohol very much. It's a struggle every day to keep from compromising her values. Much of the ins and outs of life in the Ginza are explained to us by Keiko in voiceover. She is a thoughtful woman, prone to otherwise keep what is really going on to herself. She is also crafty, having learned how to dodge men's advances and to lie her way out of scrapes. The bulk of Naruse's movie, shot from a script by producer Ryuzo Kikushima (a regular contributor to Kurosawa films), focuses on the season when life decides to pile on Keiko. An ulcer, a failed business venture, needy family members, multiple proposals--it's more than a lady should be able to take.

Keiko holds on longer than most would. As an actress, Hideko Takamine brings an inner strength that informs Keiko's outer bearing. Back straight, chin-up, smile when appropriate--these are the traits of a good hostess. Your troubles are bundled inside your kimono, the bar is not the place to let them out. This demeanor deteriorates over the course of the story, even as Keiko does her best to avoid traps she sees others fall into. A protégé's desperate actions after she opens her own bar, only to spiral into debt, serve as a cautionary tale. Yet, superstition and plain old bad luck tear at Keiko. As she grows more weary, her mistakes become more grand.

In terms of performance, the most appropriate metaphor I can think of is that Takamine sees Keiko as a porcelain doll, and with each successive scene, invisible hands are chipping away at her painted exterior. Takamine proves exceptionally capable of showing the decline. She has a sweet face and a charming overbite, and though at first her seductive traits may not be obvious, it's an actress' job to be everything to everyone; thus, the role of a woman who morphs into the thing most desired by whomever is looking at her at any given time should be ideal for a performer. Likewise, an actress needs to still be herself when she steps off set, to leave the role behind. One assumes that Takamine's own experience, having been in the business for three decades by the time she made When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, gave her a special connection to Mama.

By the time When a Woman Ascends the Stairs is in its final reel, it's hard to imagine that it can go anywhere positive without selling itself out. We have seen so many things go bust by that point, and the movie has maintained such a sense of internal realism--Masao Tamai photographs Tokyo so that its neon looks gorgeous in black-and-white--it would be impossible to accept that events take too dramatic a turn. Thankfully, Naruse and Kikushima place enough faith in their actress and the level of trust she has earned from their audience in the preceding 105 minutes to know that it's really just reliant on her to pick herself up, dust herself off, and carry on. Even better, Takamine is so good at what she does, she not only makes us believe that Keiko will carry on, but when we hear her final words, the oft-spoken greeting she gives to all of her customers, we accept that she believes them as never before. And somehow, some way, that makes us feel good for her. We want Hideko Takamine to be okay, and she has assured us that, no matter what, she will be.

* Also look for Hideko Takamine in Tokyo Chorus (part of the Eclipse Silent Ozu box) [review].

No comments:

Post a Comment