And you've got your pretty clothes

And the chauffeur drives your car

You let everybody know

But don't play with me,

'cause you're playing with fire"

The Darjeeling Limited opens with a fake out. Bill Murray, playing an unnamed business man, is running to catch a train somewhere in India. The camera is with him as he runs, but suddenly, another figure enters the screen--Peter Whitman, one of the three Whitman brothers. He's running to catch the train, as well. He passes the man, doing a double-take, almost like he knows him, before leaving him behind; Mr. Business will have to catch the next one. For a moment, though, we thought the movie was about him, or would at least feature him prominently, but it does neither--at least not in any way we know. He is seen one more time in a later montage, part of a roll call of the film's other tangential characters, a reconnecting to the collective unconsciousness of the narrative, and in that instance, we will see him at rest. But why is he there?

It would be easy to get hung up on Bill Murray. In the scheme of The Darjeeling Limited, he is a small thing, and part of the film's greater meaning relies on the Western habit of getting hung up on small things. Granted, his existence nags at us through most of the picture. I've seen it three times now and I still keep waiting for it to be revealed he's actually the father of the Whitman boys, the man whose death has sent them out on their journey of healing and spiritual discovery. It's a ghost chasing the train, and the children pass him by the way children are supposed to, already farther ahead of their parents than even they know.

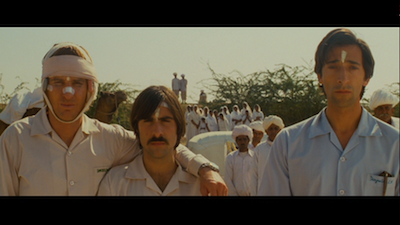

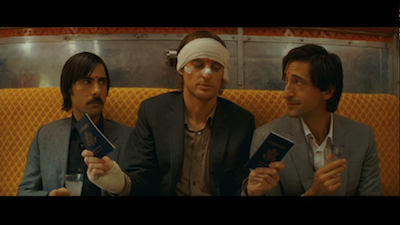

The other guys are waiting for Peter on the train. There is the eldest brother, Francis (Owen Wilson), and the younger sibling, Jack (Jason Schwartzman); that means Peter (Adrien Brody) is the middle child. It's been a year since their father's funeral, and that long since any of them have seen each other. Much has happened. From having watched the film's prequel Hotel Chevalier, available here as it was on the earlier Fox DVD, we know Jack has been in exile in Paris, where he recently was visited by a toxic lover he'd do better to forget. We will find out shortly that Peter is expecting a child in six weeks, a responsibility he is not ready for. Francis arrives bandaged and bruised, apparently having been in some auto accident. He is a successful business man, it would seem, and he has brought an assistant (Wally Wolodarsky) who will keep the boys informed of their itinerary and keep the trip moving. Francis has planned everything.

On the surface, these plans are exactly what Francis tells his brothers they are: they are on a spiritual journey, seeking to renew their familial bond and heal their wayward souls. Secretly, Francis is also hoping to find their mother (Anjelica Huston), who he has learned is living as a nun in the Himalayas. There are clearly unresolved issues here, and Francis may be the only one who wants this reunion.

The Darjeeling Limited is the fifth full-length feature from writer/director Wes Anderson, who here shares script credit with Schwartzman and Roman Coppola, a filmmaker in his own right. (He has directed many music videos, behind-the-scenes featurettes, and his own film, CQ

The title of the film comes from the train the Whitmans are riding. Though the ultimate destination will be the nunnery where their mother is holed up, there will be many stops along the way where the boys will attempt to have premeditated mystical experiences. It's a misguided effort, however, you can't plan for epiphanies. Francis is an overbearing control freak who seeks to even put a rope around chaos. He has mapped out key ashrams and brought along peacock feathers for a ritual intended to unburden them of the maladies that weigh upon their souls. Unsurprisingly, Jack and Peter can't follow instructions and it all goes wrong.

Much of the trip is spent with the brothers at each other's throats. Old resentments come up, new ones emerge. Peter, for instance, is taking charge of their late father's belongings, which rankles Francis' need to have everything locked down. Jack is pining for his girlfriend (Natalie Portman), and he creates a parallel situation by having a quickie with a stewardess on the train (Amara Karan), ignorant of the fact that she is dating the chief steward (Waris Ahluwalia). The boys are all getting blitzed on over-the-counter medicines, taking advantage of more lax prescription laws in India. They argue and even have a fist fight and make nuisances of themselves as they overanalyze every little detail of their lives. Francis wanted his brothers to get on the same page, but they haven't even agreed on the same book.

All of Wes Anderson's movies have shared themes and affectations, and after his previous film, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou [review], there was a fear he might become stagnant. The Darjeeling Limited is his attempt to avoid that. In this movie, Anderson seems to be undergoing his own transformation, tackling this potential problem head on and also addressing one of his main narrative concerns, the theme of letting go of the preciousness that at first defines and then smothers individualism. When seriously considering The Darjeeling Limited, it starts to feel like the previous films were playtime, a bunch of kids putting on a show, and this one shows a director growing up for real. Thus, the father figure, a very important component of Anderson's oeuvre, is already out of the equation, and the usually dependable mother has given up on her responsibilities. There is nothing left for the children to hide behind. Rebellious quirks like drug taking and kleptomania are neither cute nor romantic, nor is playing with exotic and dangerous things like poisonous snakes; these things now have an actual effect, they take a toll.

In this case, the snake is the first infraction of several that cause the Whitmans to be kicked off the train in the middle of nowhere. This is arguably the best thing that could have happened to them, as it finally wrenches control from their hands. They are somewhere they did not plan to be with no exit strategy. As the idiom goes, it's about to get real. When morning comes, the guys witness another trio of brothers: three local children trying to cross a river. An accident occurs, and one of the children dies. Fittingly, it's the one Peter tries to rescue. "I couldn't save mine," he says plainly, even as blood rushes down his face and he cradles the dead boy in his arms. Metaphorically, Peter is being faced with his own future and the son he is considering abandoning before he is even born. It's a heartbreaking moment that Brody plays with an intense, yet understated, gravitas. His numbed reaction speaks volumes; in this case, doing so little means so much.

The event actually inspires a different kind of letting go. In a very literal sense, the Whitmans all toss aside their luggage to jump in the river--luggage that was once owned by their father and even bears his initials. In any road trip, the physical baggage characters bring with them is merely a stand-in for their emotional baggage. It's also important to note that just before the accident, the computer printer Francis uses to make his laminated itineraries falls and breaks--yet another sign that the comfortable world of modern convenience is no longer valid. They must discard the superfluous before they can realize what is important. The aftermath of the tragedy is the first time the trio is genuinely quiet. Words fail them.

Anderson chooses to drop a flashback in here, and he couldn't have timed it better. He cuts from the child's funeral to the Whitman boys in the back of a limo on the way to the funeral for their father. The scene is already in progress when we enter, and the first line of dialogue is "I can't believe you just said that." We are back to the siblings in a quarrel, engaging in more of their ill-conceived plans. Peter demands they stop and pick up their father's roadster from the repair shop. It's not fixed, but they try to take it anyway. It's these guys in a nutshell--always trying to push a car out on the road even though it has no battery. It's crucial, however, that the failure of this plan unites them. Compare the shot of them ready to fight the truck driver in the middle of the street to them together at the funeral, and then think of this again later when they finally regain their common ground just before leaving India.

Prior to this departure, the most connected moment the brothers have in the movie--I prefer the word "connected" to "spiritual," honestly--is when they are communing with their mother. It's another scene where silence is important, even if we aren't sure that dear ol' ma isn't conning them to get out of answering their accusations. She suggests they sit quietly and just feel what they are feeling, their faces and their energy will communicate what words cannot. Anderson sets the camera in the center of their circle, and it pans around, face to face, chronicling their changing expressions. This exercise causes not just contentment, but the ability to reach out to the world beyond. It reconnects them to everyone else. Anderson cuts to one of his famous "dollhouse shots," the aforementioned train montage. The camera now pans across a long string of cars. There is no exterior, and we see everyone inside. We see the people the Whitmans have encountered on their way here, we see Peter's pregnant wife, and we see Bill Murray and Jack's girlfriend again. It's also the scene that uses the Rolling Stones song "Play With Fire," the opening lines of which I quote at the start of this article. Those six lyrics succinctly sum up so much of what this movie is about. Consider Mick Jagger to still be in his role as the tempter from "Sympathy for the Devil," and the mystical implications of the tune become far more flammable. "Your material world is easy, but the world I offer, a place where you let your emotions run free, is the one where you actually risk something." Hence, the caboose of the train houses the specter of death--the man-eating tiger that lurks outside the nunnery walls.

It's important to consider the music in any Wes Anderson movie. He picks his songs carefully, and they tend to enhance the meaning of the action. Elsewhere in the film for instance, the Kinks song "Strangers" contains the powerful statement, "I've killed my world and I've killed my time." The Kinks are another British Invasion-era rock group that plays an important part in the Anderson's prior filmography, but Anderson's previous use of the Stones still has tremendous dramatic resonance. A couple of their tunes provide the soundtrack for the revealing moment between Margot and Richie in The Royal Tenenbaums [review]. Arguably, the band is as important to Anderson's work as to Martin Scorsese's--though the two filmmakers gravitate to very different facets of the Stones catalogue.

I've argued before (and I'm certainly not the only one to do so) that Wes Anderson's output should be considered as one continuous thread, each film informing the other, as he builds on his themes and his unique vocabulary. Perhaps it is the familiarity of Anderson's coded visual language that makes it easy for some to dismiss it. Particularly in The Darjeeling Limited, the way Anderson's style so languorously hangs off his players makes it seem like he is phoning it in. Yet, I find when I try to put together the pieces and assign each Darjeeling character his place in the lexicon, it is not so easy. The emotions are more complex. They don't fit inside the picture frames as easily as the Tenenbaum children fit on their wall of accomplishments.

Jason Schwartzman in particular could be seen as playing his Anderson avatar all over again, returning to his career defining Rushmore role [review] and bringing Max Fisher into adulthood. If Jack is Max, he still invents stories, still struggles with unattainable love, but he has less self-belief. Again, the details are important, which might be why its so disconcerting in Hotel Chevalier when the first thing Natalie Portman does upon invading Jack's space is to rearrange his things. Everything has been put in the spots where Jack intended them to reside; he is an Anderson character through and through, he is establishing his own environment. It's why whenever he makes an important move, Jack cues up Peter Sarstedt's "Where Do You Go To (My Lovely)" on his iPod. He is scoring the film of his life.

Likewise, the stories he writes are all about him, even though he denies it. On one hand, he is chasing something (the book on his bed in Hotel Chevalier is the marvelous twofer of Nancy Mitford's The Pursuit of Love & Love in a Cold Climate: Two Novels

Despite this reliving the past, more should be said about how much Wes Anderson has pushed himself out of his comfort zone for The Darjeeling Limited. He has left the familiar terrain of his previous inventions and gone in search of reality. Rushmore existed in an imaginary place where rich and poor are divided like an S.E. Hinton novel--or a clichéd inner city movie, something Max might turn into a stage play. In The Life Aquatic, Anderson sort of pretended to go out into the big, wide world, but it was still a fantasy world. For The Darjeeling Limited, he has gone someplace foreign to him, one that resists his molding it. The Whitmans think they can wander through India being who they are, relying on their white American privilege, but the country doesn't embrace them in this way. Francis sits down to get a shoeshine, and the shoeshine boy steals his $3,000 shoe.

You could actually consider that an extended metaphor for storytelling itself. An author may want to control where the muse takes him or her, but the muse does as it pleases. This bears more weight when we stop and think about Francis as the stand-in for Anderson, as well as considering further the history of Owen Wilson's roles in previous Anderson productions. (Remember, he co-wrote Bottle Rocket [review], Rushmore, and The Royal Tenenbaums.) In Bottle Rocket, he establishes himself as the leader and schemer who imposes his self-belief on the others. He gets beat up for it, though not to the degree of which he is mangled in The Darjeeling Limited. This would mean the toll for setting the narrative has increased. (Note, too, Francis' initial explanation of how he crashed his car has echoes of Eli Cash plowing into the Tenenbaum home.) Perhaps this is also why Wilson's performance is the most mannered--he is mimicking the director.

This leaves Adrien Brody to be the stand-in for Roman Coppola, and both are newbies in the Anderson universe. Peter at times could be seen as more of an observer than a participant, sometimes even an outsider--he is not part of the regular routine, and when he takes action, it can be disruptive. Given Coppola's famous father, whose footsteps the son has followed in, it makes the fact that his avatar clings so closely to the dead man's things all the more revealing. The stolen prescription sunglasses, then, is a symbol for borrowed perception, of taking the patriarch's way of seeing as his own. Francis' jealousy, then, may be Anderson's (a stretch, to be sure, but let it have its moment). He wishes to be part of the cinematic lineage. He even has his character adopt the elder Coppola's first name!

The lack of audience and critical response to The Darjeeling Limited is damning in its own way. (I'm not a big fan of mob rating, but Rotten Tomatoes currently has it at a so-so 68%.) I've long believed that audiences resist growing with their favorite artists. They are too enamored with the first time they encountered whatever entertainment that artist has offered, and so resist when the creator goes too far from that initial spark and seek to put him or her back in the original box, seizing on anything that is repetitious as somehow actionable even as they insist the artist deliver more of the same. (At this point, dismissing The Darjeeling Limited is such a knee-jerk reaction, it tends to cause me to discount the person who has it with the same unqualified reflexiveness unless they can offer a considered response.) If The Darjeeling Limited is the end of a cycle, it's one that ends as it began. Bottle Rocket was a road trip, too. We have come full circle.

So have the Whitmans. By the end of The Darjeeling Limited, they are one, instead of three. Anderson has unified his characters, and they now wish on a single peacock feather. This is followed by them once again having to chase a train, though this time it isn't Peter on his own, and catching it requires another discarding. Calling back to the tossing aside of the luggage at the river, the boys are going to have to shed that baggage for real. Once they do, they surrender themselves and accept each other for who they are. Their flaws may be annoying, but hey, that's the way they are made. Embrace the imperfection.

It makes for an ending that satisfies on all levels--intellectually, philosophically, emotionally, and dammit, even spiritually. In the past, Wes Anderson has been criticized for not going deep enough. In The Darjeeling Limited, he dives down as far as he can go, and by having worked for the treasure, the one he returns with is one he deserves and, thus, all the shinier.

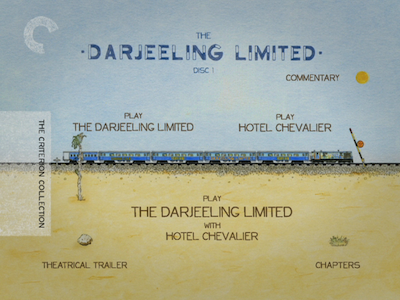

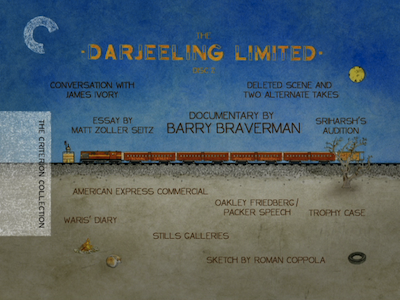

This is the second edition of The Darjeeling Limited, though the first to be on the Criterion label and also the first to also be available on Blu-Ray

Amongst the bounty of extras, aficionados will likely be most intrigued by the audio commentary featuring Anderson, Schwartzman, and Coppola (something I'll explore later, now that I've worked through my own theories on the film), as well as a 20-minute conversation between Wes and James Ivory about Indian movies and the music in The Darjeeling Limited, much of which was lifted from Merchant Ivory productions and Satyajit Ray films. We also get the full American Express commercial starring Anderson (as well as Schwartzman and Coppola, too), and a trio of deleted scenes/alternate takes.

My favorite extra, though, is the video essay by Matt Zoller Seitz, who made that marvelous series dissecting Wes Anderson's style back in 2009 (still online starting here). I wish there was a way that all five of those had been put on here, as well, but Seitz's Darjeeling Limited-specific segment created for this disc is still fascinating and insightful. And he probably only uses about half as many words as I did to say twice as much.

Watch the trailer for The Darjeeling Limited.

This disc was provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.

3 comments:

Your reading of the Murray character as potentially the brothers' father is really intriguing. I definitely hadn't thought of that. Up until this point, I had regarded Murray's presence as a little cinematic joke: after all, the scenario of running after a train perfectly recreates a hypothetical suspense situation Truffaut and Hitchcock discuss in, well, Truffaut's Hitchcock book. Truffaut later actually filmed that opening in LA PEAU DOUCE... So, if anything, it's certainly a salute of sorts.

Having known many absent business/executive fathers my take on the Murray character is that he is just an archetypical father figure concerned with providing material goods as his ultimate and only function. Not their father but THE absent father always missing the train.

BTW can anyone tell me who is the background character running along the brothers in the scene when they leave their luggage? It is a small running shadow right in the middle of the screen (6:08 to 6:40 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ni7nn792v0&feature=player_embedded)

Innteresting thoughts

Post a Comment