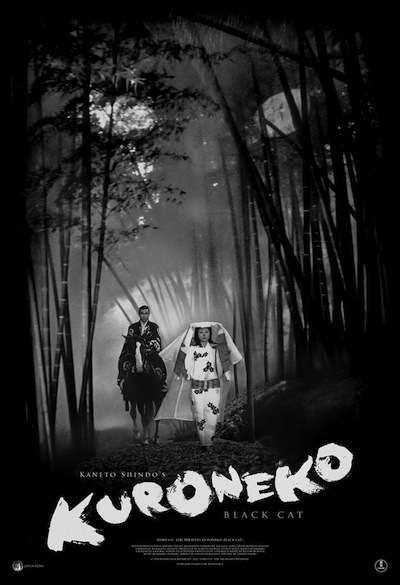

Kaneto Shindô's 1968 horror movie Kuroneko (a.k.a. Black Cat) is a creepy mood piece that starts with shocks before settling into a far more effective mode, digging its claws in the viewer to inject a nearly imperceptible poison.

The film opens with a harsh event: a band of starving samurai finds a remote farmhouse where two women live alone. A mother (Nobuko Otowa) and her daughter-in-law (Kiwako Taichi) are inside eating a quiet meal, having been stranded three years prior when the man of the family was conscripted into the army. With no one to protect them or their home, the brigands eat the food, rape the women, and burn the house down. The scene plays with no dialogue, and the most gruesome events occur off camera, the drooling faces of the onlookers being enough to turn our stomachs all on their own.

When the smoke clears, the house is destroyed, but the bodies of the dead remain relatively untouched. A black cat crawls into the wreckage and seemingly revives the women. It's implausible, sure, but Shindô's quick cut technique hips us to the fact that something beyond flesh-based logic is going on here. We are in a supernatural world.

Cut to a dark night outside the gate to the estate of the village nobility. A lone samurai passes on his horse. As a cat meows in the distance, he is approached by a young woman dressed in white. It is Shige, the daughter from before. She convinces the warrior to escort her back to her house, where she and her mother give him sake and the promise of something more. Only, when he collects, Shige's kisses turn to deadly bites. She gouges his neck and drinks his blood. Come morning, the house is gone, but the dead samurai is still there.

Kuroneko is a mystical revenge movie, a ghost story about two wronged women exacting vengeance on the warmongering men that are tearing their country apart. It covers some similar ground to Kaneto Shindô's earlier movie, the eerie and often harrowing Onibaba [review], in which a similarly abandoned pair of women earn their way by killing passing swordsmen and stealing their armor. In Onibaba, the return of the lost son and husband exposes the crimes and shifts the drama into even more macabre directions. In Kuroneko, the return of the soldier boy is almost the opposite. The ghost story takes a turn when Gintoki (Kichiemon Nakamura) emerges from combat as a celebrated warrior. He is promoted in the ranks and dispatched by his master (Kei Satô) to take care of whatever is killing the men.

Naturally, Gintoki is taken aback when he discovers whom the ghosts are, but instead of dispelling them via a deadly battle or a traditional exorcism, Gintoki settles back into a semblance of home life. Kuroneko becomes almost a love story, albeit a morbid one, as the husband returns to the house night after night to make love to his dead wife. It's a glacial seduction, both in terms of temperature and pacing. Life in Kuroneko nearly slows to a crawl--only it's a state that can't last. There will have to be a reckoning.

Shindô is a particularly skilled filmmaker when it comes to making the supernatural come alive. There are several excellent special effects in Kuroneko. Some of them are traditional sleight-of-hand: at one angle, we see the true nature of the ghosts, but in the next cut, they have returned to normal. Shindô loves to use a choppy montage to unsettle the viewer and pull us into the netherworld. He also gets clever with optical effects, and he portrays the ghostly manor where the women lure their victims as a kind of landlocked sailing vessel. It moves through natural space, drifting through the surrounding forest, never locked to one place on the corporeal plane.

As good of a ghost story as it is, however, Kuroneko is far more than a simple tale of succubae going bump in the night. As with Onibaba, the filmmaker is using the fantastical as background for exploring human nature. In particular, Kuroneko is a damning critique of societal divisions and the pecking order of masculine leadership. The higher up the ladder, the more vain and ridiculous the men behave. The head of the clan sits behind a screen, as if he were some great and powerful Oz passing orders down to the lower ranks, while Gintoki's superior, Raiko, is a hairy, preening beast. When Gintoki spins an embellished tale of how he conquered an enemy referred to as "The Bear," his description of the man's furry body could just as easily be applied to the man he is telling it to. The male animal is large and indiscriminately violent, whereas the female power lies in wait. A cat is stealthy and precise. They keep the true color of their fur hidden.

All of these elements build to an effective climax, Shindô pulling out all of his tricks for a close-quarters showdown and a bittersweet finish that stays true to Kuroneko's cynical worldview. As the final images continued to haunt me, I had to ask myself whose side I was on and why. Who was I meant to sympathize with or feel sorry for? Gintoki obviously had nothing directly to do with the murder of his family, but he is part of the system that made it possible. Hell only comes to Earth when humanity clears a path for it.

Kuroneko is currently playing in limited engagements around the country. My fellow Portlanders can see it at Cinema 21 starting November 5. Check the Janus Films website for dates near you.

No comments:

Post a Comment