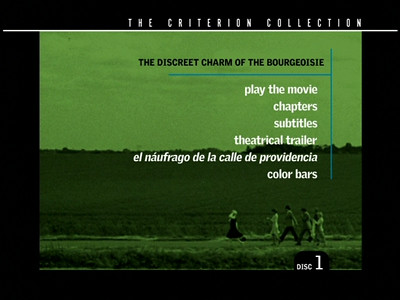

At several intervals in Luis Bunuel's biting satire, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), the director impishly cuts away from the main story to show us his six characters walking down a desolate road in the middle of an open plain. They are fully dressed, the men in suits and the women in dresses, and slightly hurried without looking too concerned. We never see where it is they are going. Is this a kind of purgatory they have found themselves in, or is it merely a symbol of the futility of their petty lives? Or could it be that these things are one in the same?

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie is an episodic savaging of the well-to-do French middle-class. An old surrealist, Bunuel builds a puzzle box of a movie, full of stories within stories, dreams within dreams. At several points, we cut to one of his dyspeptic gentlemen waking from sleep, horrified by what he--and by extension, we--just saw. Amusingly, the dreams often go several scenes back, including another guy waking up in bed, so that the second dreamer was actually imagining the first dreamer and his disturbing vision. Not unlike watching a film where the characters might suddenly become aware they are being watched. Or if the viewer could turn around and discover that he or she is being filmed.

The vignettes all revolve around meals that six friends try to partake of together. Luncheons and dinners are how these people congregate, the way they gather to share their banal views on politics and the world around them. They are demanding of the service class and blind to their problems. On their first outing, where the would-be diners are required to a go to a restaurant due to a mix-up with dates, they discover that the owner of the inn has died and is in the next room waiting to be taken to the funeral parlor. The employees he left behind plan to go on with their duty and still serve customers, but the friends all leave rather than have their meal. Not because they feel bad, but because they find it inconvenient. They can't even see the necessity of work, that these others must carry on in order to survive.

All of the meals this group tries to sit down to are interrupted in similar ways, and in each, something is revealed about the humanity the bourgeois are so desperate to bury beneath their tailored manners and carefully chosen banter. One lunch is postponed due to the host and hostess, Alice and Henri Senechal (Stephane Audran and Jean-Pierre Cassel), having sex outside in the bushes rather than be heard doing it in the house. Not that it wouldn't be easier to control their urges, but suppressing them would be admitting they have them. One dream of a failed dinner party sees the group on stage, mocked by an audience, Henri unable to remember his lines. In a dream immediately after, Rafael (Fernando Rey), the South American ambassador of the fictional country Miranda, shoots the host, an army colonel (Claude Pieplu), for insulting his country; again, not because it's untrue, but because you don't say such things out loud. This is the same group, after all, where the men smuggle cocaine into the country but will sit around sipping martinis and denouncing drug addicts as disgusting.

Bunuel clearly finds the social mechanisms of the bourgeoisie to be hilarious, and the discreet charm he is looking for encompasses the hypocrisies and the foibles that they try to pretend don't exist. Greed, hunger, lust, these are all things they assume of the common man, but never of themselves. The director's scenarios are like little pranks he plays on his subjects, provoking them to react. At the same time, the laughter has a morbid timbre. A metaphysical dread hangs over the movie. Again, I think of purgatory, that Bunuel has trapped these dead souls in his film until they can figure out for themselves how empty their lives are. The specter of death hangs all around them. In the dinner party play, they are prompted to invite a ghost to sit with them. One solider whom they meet twice tells them stories about his dead mother, one allegedly a memory where she instructs him to kill his father, another a dream where the ghouls he meets seem to intimate that he is as dead as they are. “You smell like earth,” he says to one, only to earn the reply, “So do you.”

In the end, the fate that Bunuel's dinner party suffers is that of their own making. Each interruption carries with it the fear of punishment, that sins will be exposed. It's ironic, then, that when the punishment does come, there are no charges leveled against them, and of course they admit to nothing. Yet, when Rafael destroys his own escape by exposing himself in order to get another bite of lamb, the implication is obvious: they do it to themselves. Of course, it also makes sense that we are now in Rafael's dream, and upon waking, having learned nothing, he runs to the fridge to devour some leftovers like a wild dog tearing into roadkill.

Since this is Bunuel, religion does not escape being parodied. The character of Monsignor Dufour (Julien Bertheau) is actually the most interesting of the lot, having the most complete story arc of any of them. He comes to the Senechal house on the day when the couple is rutting in their garden with the same sort of impulse control that got Adam and Eve expelled from Eden. With the others already having fled, fearing a police raid, and the maid (Milena Vukotic) at a loss to explain where her employers have gone to, the Monsignor takes it upon himself to fulfill the purpose of his visit. He has heard that the Senechals have fired their gardener, and he would like to take over the position. He goes down to the gardener's hut and gets dressed in the uniform, relishing in the straw hat and the tools of the trade the way an s&m dabbler might fetishize leather boots and whips.

When the Monsignor at last meets Alice and Henri, he is dressed as a gardener. They rebuke him, not believing he is a priest. When he returns wearing the uniform of his office, they suddenly kowtow to him, everyone involved completely missing the analogy to a Christly parable about how the those who lack spirit will not recognize God when He is standing in front of them.

Of course, the Senechals aren't the only ones to blame, the Monsignor is also guilty of kowtowing to these wealthy and vapid people while also being smug and patronizing to the poor who truly seek guidance, like the maid who honestly believes or the doubting peasant woman (Muni) who comes to retrieve him to perform last rites on a dying man (Georges Douking). He listens to them, but then dismisses them with empty platitudes. He doesn't even connect the dots when he is told the ailing man is a gardener who recently lost his job. This is the very gardener the Monsignor has replaced! A deeper connection is revealed, however, when it is discovered that this is also the man who had killed the priest's parents when he was just a boy. It's like a scenario out of a sweaty potboiler. No wonder the Monsignor is obsessed with gardening, he has been walking in the shoes of the killer who orphaned him!

When the dying man asks for forgiveness, the Monsignor goes through the motions and gives him absolution. He then picks up a shotgun and murders the murderer. Just as it is in everything else, the clergy also say one thing and do another.

3 comments:

Nice summary of a wonderful film. I like your comment about Adam and Eve and the rutting hosts. Also the part about the bishop and his fascination with the gardener's clothes.

I just watched this again for the first time in many years. Timeless!

having watched this confusing film for the first time this evening, your post-mortem helpful in making sense of the different storylines; the scene with the dead inspector/torturer also deserves mention

your analysis helped a lot to get some hold of this surreal movie.

Post a Comment