"A legend is entitled to be beyond time and place."

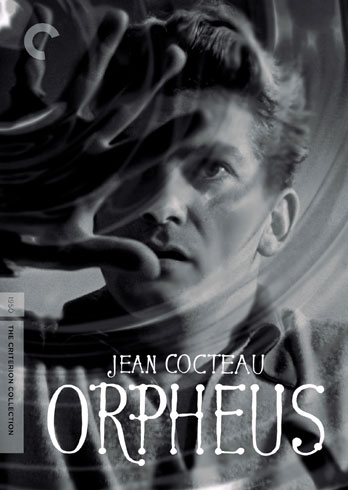

Like many folks my age, my first exposure to Jean Cocteau's 1950 art film Orpheus was seeing the famous image of Jean Marais laying in a puddle, sleeping over his own reflection, as the cover to the Smiths single "This Charming Man." With his up-do coif the right combination of styled and messy, Marais bears more than a passing resemblance to Morrissey; then again, it's really the Smiths singer who was co-opting the French actor's look. The image itself had oodles of mystery, a combination of narcissism, romance, and fatalistic morbidity that could inspire a lifetime of bad poetry. I even had a poster of it on the wall of my college dorm, some ten years before I would ever see Orpheus for real.

Watching the film again, the choice of the Marais photo still as a record sleeve makes more and more sense. Cocteau molds the mythical figure into a jazz-age outsider. He is a bard whose popular verse has made him an outcast amongst his bohemian peers, and his brooding manner endears him to teeny boppers nearly as much as his chiseled matinee-star good looks. It's the kind of jarring dichotomy between artistry and fame that Morrissey and his co-writer, Johnny Marr, would infuse their music with. For as much as they were a jangly indie guitar band, they were also a pop band. And for as much as Orpheus is a high-minded art film, Jean Cocteau has also made a pop art masterpiece, employing all the funhouse tricks at his disposal to create a raucous cinematic entertainment.

"Orpheus, your gravest fault is knowing just how far to go too far."

Cocteau's Orpheus has its origins in the famous myth of the troubadour who traveled to Hell to rescue his soulmate, only to fail to live up to the restrictions of his deal with Death upon returning to Earth, but the French director has updated and molded the material to fit the times. Set to a jazzy score by Georges Auric, it prefigures rock 'n' roll in surprising ways, with touches of the skiffle-beat musicals and juvenile delinquent movies that were to soon spring fully formed from Elvis Presley's gyrating hips. The movie opens in a bohemian café. Orpheus has stopped in for a drink, only to suffer the open scorn of his peers and rivals who resent his success. The poet is understandably defensive, since he also has his own anxieties about his flagging abilities. Accomplishment is a difficult mistress to keep maintained in the style to which she has become accustomed. [For another variation on the story, see also Black Orpheus]

On this particular day, a Roll's Royce also delivers the latest enfant terrible of verse, a drunken teenager named Cégeste (Edouard Dermithe). He has just published his first chapbook under the title of "Nudism." It is a collection of blank pages, like John Cage's concertos of silence, and Cocteau's perverse joke on the avant-garde. The car belongs to Cégeste's patron, a dark-haired ice queen known only as the Princess (Maria Casarés, Children of Paradise). Its stoic driver is Heurtebise (François Périer, Nights of Cabiria). Before days end, the café will erupt in a rumble of poets, and Cégeste will be struck down by a pair of motorcycle riding messengers of death. Orpheus will end up in the Princess' car, entangling him in a supernatural plot he didn't bargain for.

As the Rolls Royce drives into unknown territory, Orpheus becomes increasingly aware of the strange situation he has stumbled into. Coded messages filter in over the radio, and the Princess refuses to answer any of his questions. The motorcycle riders are waiting for her at her home, and once there, Cégeste is also restored to life--or a semblance of such. The Princess, as it turns out, is Death herself, and Orpheus is her new fixation. She leaves him in his world, but commands Heurtebise to stay by his side. The driver takes Orpheus home, only to find that there is a scandal surrounding his disappearance. His wife, Eurydice (Marie Déa, Lelouch's Marriage), is hiding from reporters who want to know what happened to Cégeste. A police inspector (Pierre Bertin) is in their kitchen, as well as Aglaonice (Juliette Gréco, Elena and Her Men), a friend of Eurydice's who already hates Orpheus. She is a member of a group called the Bacchantes who will eventually come looking for the poet's head.

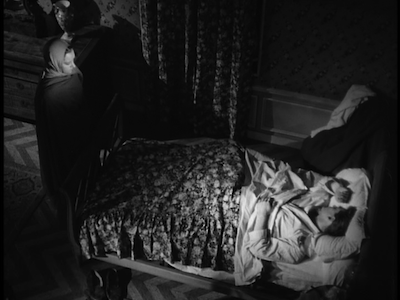

For as strange as this sounds, it only gets stranger still. Orpheus starts spending all of his time in the garage, listening to the radio in the Princess' Rolls, waiting for more poetic non-sequiturs from the beyond. He becomes so enraptured, in fact, he fails to see Heurtebise's growing affection for his wife or heed the warnings when Death comes to claim Eurydice. The Princess is as obsessed with Orpheus as her ghostly driver is with his spouse, transgressions that cross the untraversable lines between this life and the next. Once Orpheus finally wakes up to what is happening--the movie makes multiple references to dreams, asserting that this may all be the poet's nightmare--he compels Heurtebise to take him below ground to find Eurydice and bring her back.

This could all be some serious stuff in the wrong hands, but Jean Cocteau approaches his mythic material playfully. He sees the classic story as a metaphor for artistic passion. Orpheus is so taken with his melancholy muse, he ignores the real world, causing damage to his relationships and forcing some reconciliation between what goes on in his head and what is happening in the flesh. Marais plays the poet as a vain, self-serious brat, an eternal teenager who refuses to leave the comfort of his adolescent humors. His relationship with Casarés' raven-tressed Death is practically a gothic parody. The pouty poet is obsessed with his own mortality, and how could he not be flattered to discover that mortality is also obsessed with him! Juxtaposed with this, Marie Déa's blonde beauty plays to the fairy tale conventions of innocence. She is sweetness personified, an expectant mother, the ill-treated lover. Naturally, the dependable Heurtebise, who committed suicide for want of a woman, would be drawn to her; he works for the dark side, he's seen its flaws. It's marvelously realized melodrama, timeless and hormonal, broaching dire subjects but with a light, sardonic touch. This is a romance, after all, where one of the lovers easily flips between the woman he intends to save and the one who took her away--made all the more amusing by the fact that Marais was Cocteau's former lover and Dermithe was his current one at time of shooting. It's not exactly the most lovesick scenario, but it has its charms.

In fact, Cocteau's tiptoeing through the afterlife is actually a lot of fun. His vision of Hell is imaginative and unique, using the ruins and rubble that would have been commonplace in post-War France to craft an image of damnation that is both a sad remembrance of the tragedy that hit his country only years before and a reminder of the resiliency that pulled them through. While some of his special effects seem antiquated and rickety today, Cocteau's films work because the artist embraced the joyous possibilities of motion pictures with a childlike exuberance. The movie camera is his toy, and he wants to learn everything he can do with it. Running the shot backwards, rear projection, make-up, and literal smoke and mirrors are all weapons in his arsenal, and even though he was already an accomplished auteur by this point (he had made his wondrous version of Beauty and the Beast [review] four years prior), he approaches each effect with a gleeful naïveté. Cocteau on a movie set is like a child in a magic shop, eager to sample each trick, always willing to believe that the illusion is real.

It's this wild abandon that keeps Orpheus feeling fresh after all these years. It's why new packs of youngsters and movie buffs keep rediscovering Cocteau's experimental flights of fancy and going along for the ride, maybe identifying themselves in the archetypes, maybe just digging Orpheus for its style and passion. It's the same reason a band like the Smiths or an author like J.D. Salinger has a legacy that far exceeds their output. Jean Cocteau was 60 when he made Orpheus, but he was still a teen rebel, a rock star before there was any such thing. Some dudes start out cool and they stay cool forever.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVD Talk.

Please Note: The screen captures used here are from the standard-definition DVD released in 2000, not from the Blu-ray edition under review.

No comments:

Post a Comment