Let's face it. If we were to take a poll to find out what film genre has the greatest tendency for mawkish sentimentality, it would probably be films about the lives of teachers. Whether it be the countless tales of inner-city educators pushing their troubled pupils to be all they can be, or the variations of Mr. Holland lamenting their lost opuses, romanticized versions of a very tough job quite often go for the emotional jugular in the most obvious and direct of ways.

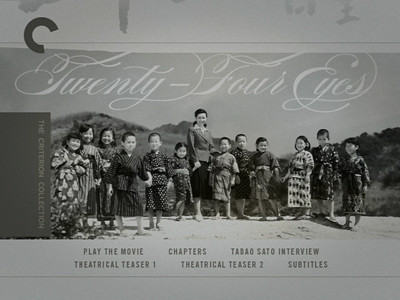

Thus, when a movie like Keisuke Kinoshita's 1954 schoolroom epic Twenty-Four Eyes (Nijushi no hitomi) comes along, it's cause for celebration. As with any abused genre, it's not the form that's bad, just the use of it. Either that, or Twenty-Four Eyes, now coming to DVD in North America for the very first time courtesy of the Criterion Collection, is the exception that proves the rule. Sure, it's ripe with sentimentality, but we need to get over using that as a buzzword for "bad." Humans are sentimental creatures, and we turn to movies to make us feel. Sentimentality done poorly makes us groan, but when done well, it inspires a true gut reaction. If you don't tear up at least a couple of times in Twenty-Four Eyes, you apparently have rocks where the rest of us have brains and hearts.

The focal character in Twenty-Four Eyes is Hisako Oishi, played with a mannered grace and honest tenderness by Hideko Takamine (When a Woman Ascends the Stairs). In 1928, Miss Oishi is sent to a poor seaside village to test out her newly minted teaching license on the first grade class. Seen as a "modern girl" because of her western-style clothes and because she rides a bicycle to work, Hisako is mistrusted by the adults of the town but quickly earns the love and admiration of her twelve students. In their eyes, the twenty-four alluded to in the title, she sees the sparkle of a future full of possibilities, and in her, they see someone who cares whether or not they achieve them. Her last name actually translates as "Big Stone," but because she is short in stature, the kids nickname her "Miss Pebble," unwittingly creating their own Zen koan. In the smallest pebble is the greatest of power.

Twenty-Four Eyes spans nearly twenty years, following the ups and downs of the relationship between Hisako Oishi and her many students. A prank the kids pull on her causes her to tear a tendon and cut her inaugural year short, but the class catches up with her again in sixth grade when they find her at the central school in the next town over. From there, she watches them all graduate into different lifestyles, some going on to high school, some working for their families, and others marching off to war. For her own part, Hisako gets married, has her own children, and lives through WWII and personal loss, only to come full circle and instructing the sons and daughters of her original twelve in the little schoolhouse where it all began.

With a running time of just over two-and-a-half hours, Kinoshita manages to deliver a lot of story without ever getting caught up in overly lengthy tangents. It might have been tempting to follow the little girl whose family goes bankrupt and has to move away, or to see any of the male students lost on the field of battle, but Kinoshita has a keen sense for how people flow in and out of our lives. He sticks with Hisako the entire time, rather than let any of the more romantic characters take him away from her story. In fact, this may be how he avoids falling prey to crass emotional ploys. Seeing a 12-year-old girl reduced to begging in the streets or a big death scene as Allied shells rip up the terrain all around the dying would have forced a sense of loss on us; instead, it's the not knowing that hurts, the drifting away of these characters that we've invested our time in alongside Hisako.

Twenty-Four Eyes was a popular film in Japan when it was released, and it's still considered a national treasure to this day. I imagine for the Japanese it served a similar purpose to what William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives

Just as it would have been easy to become overwrought when detailing the personal tragedies and triumphs of Hisako and her students, so too could Kinoshita have gone astray my being more heavy handed in his anti-war message. In the years between Hisako's first class and the advent of WWII, Japan went through the Great Depression and had a continuing conflict with China. The rise of militarism offered young men a chance to have a career, gathering such steam that it practically created a need for a greater conflict. Rather benign expressions of peace cause trouble for Hisako more than once, nearly getting her branded a "Red," and without putting too fine a point on it, Twenty-Four Eyes indicts the prevailing attitudes that would allow such a bloodthirsty and paranoid way of living to take hold. Patriotism is often the banner under which a nation rends its own flesh from its bones.

At the same time, Kinoshita, like his soft-spoken protagonist, is a humanist, and he's not going to point a finger without also holding out a hand in an offering of hope. One need only look at the great care with which he photographs the mountains and the seashore of the fishing village to see how much the director loves his country. By having Hisako return to the rundown schoolhouse and start again, to have her inspire a new generation the way she inspired its parents, is to say that life can go on, that the Japanese people could get back on the proper path, and that the future rested right where it always did--in the dreams of the young.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

No comments:

Post a Comment