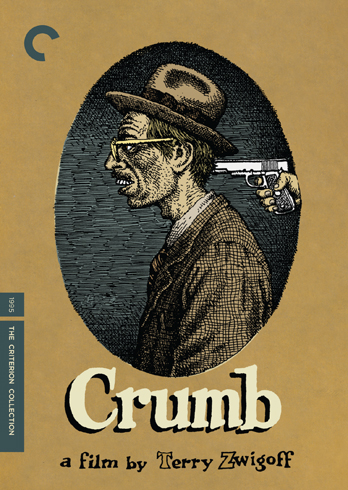

There is so much loaded into the above statement by Charles Crumb, that one can't help but immediately seize on it. It is so packed with meaning and says a multitude of things with such poetic economy, Terry Zwigoff had to know immediately upon hearing it that it would serve as ideal punctuation for the epilogue of his 1995 documentary Crumb. What had started out as a film about legendary underground cartoonist Robert Crumb ended up not just a portrait of the artist as a middle-aged man, but of his family as well. The fact that Zwigoff composes the film with such attention to detail, and yet absent of even a whiff of judgment, has made it one of the most compelling documentaries of our times, as well as one of the most perceptive and illuminating examinations of both the perils and giddy joy of the creative life.

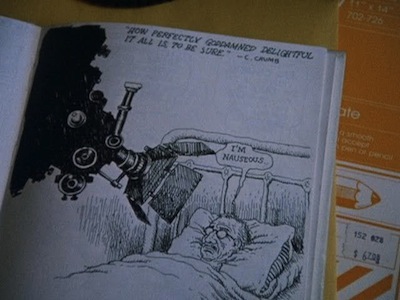

Though Charles Crumb is credited with the phrase, Robert Crumb is the one who shares it with Zwigoff, having scribbled it at the top of a drawing he made to illustrate the anxiety the filming process had been causing him. Robert and his wife Aline Kominsky were preparing to move to France at the time, a fitting end to the filmmaking schedule. Zwigoff had asked Robert if he would miss his family or otherwise felt bad about leaving them. The artist says no, he never sees Charles or his mother, and the interview session reminded him why. That quote was a favorite phrase of the older brother's, and he would say it to deflate any happiness his younger siblings might find in anything that struck their fancy. Imagine it said sarcastically. The underlying meaning is that what Robert liked was stupid and liking it made him an idiot.

And yet, it could also be the Crumb family motto, and it need not be as sardonic as all that. There is something strangely American in how off center this American clan is. Imagine Robert Crumb and his brothers standing on a hillside, the sun setting in the sky behind them, at the end of an old Hollywood movie. "How perfectly goddamned delightful it all is, to be sure," is suddenly "As God is my witness, I'll never be hungry again."

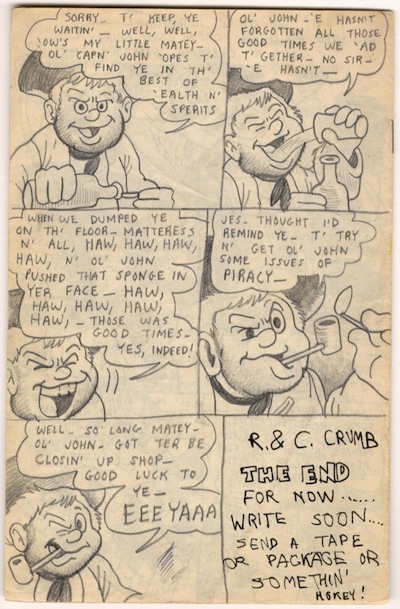

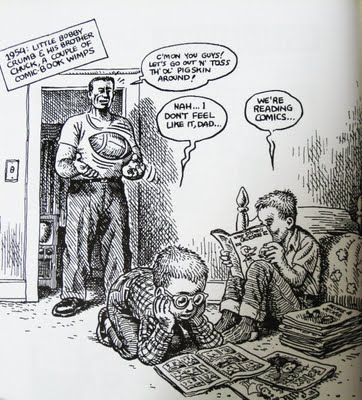

Crumb is a two-hour perusal of the Crumb family photo album. Though a good portion of it does chronicle R. Crumb's rise to infamy as a satirist and counter-culture cartoonist, the full image doesn't really come into frame without the other boys. Robert is the middle child, and the youngest is Maxon. (Two sisters refused to participate in the movie. Can't say I blame them, lord knows what was done to them in that household when they were young.) All three boys possess a natural ability for art, though it was Charles who literally forced them into comic books, particularly Robert, who saved the fruits of their labor all these years. He's got stacks of the fancy books he and Charles put together, trading story lines and ideas, developing their unique style. There is an obsessive-compulsive trait to both of their aesthetics: R. Crumb is known for his meticulous cross-hatching and immaculate ink lines, whereas Charles developed a "wrinkled" style. As he got older, everything he drew was decorated in endless loops.

A comic book page by the young Crumbs

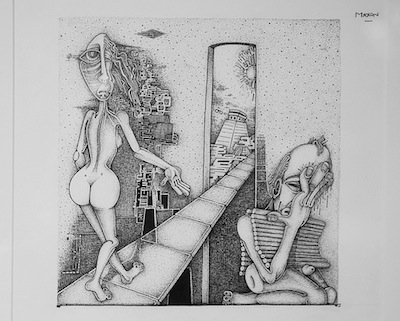

Maxon's story is slightly different. He started drawing when he was older, and the sudden release of passion resulted in an epileptic seizure. He is more of a fine artist now, but in his paintings, there is a consistent mechanical theme and also a vague obsession with undulating, melting lines, reminiscent of the clocks in Dali's "Persistence of Memory." At the time of filming, Maxon was living a pseudo-monastic life, begging for change in San Francisco. In Crumb's most discussed scene, which comes not long after Maxon has confessed to a misspent youth pulling women's pants down in public, the clearly deranged painter is meditating on a bed of nails while swallowing a chord that he will pass through his digestive track to clean it out. If Charles had the same cord, he would probably wrap it around himself like his beloved wrinkles; for Maxon, it's another undulating line.

Art by Maxon Crumb

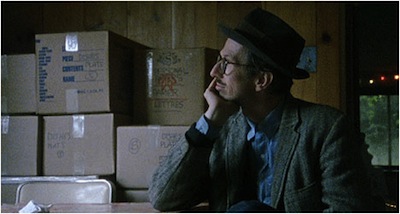

Charles lived on the other side of the country. He never moved out of their childhood home, and he has turned into a recluse that never goes outside and only bathes once every six weeks. He's on medication for depression, and he admits to suicide attempts and previous homicidal thoughts. (The sad coda is he did kill himself not long after his interview was filmed.) There is some intimation that maybe Charles, who was a regular troublemaker as a youngster, turned inward to avoid even more dangerous impulses. Many of the comics he made when he was a teen riff on the Treasure Island

Robert Crumb listens to both his brothers indulgingly, laughing at their quirks, but never in a way that is mean-spirited. Robert has a habit of laughing at just about everything, including himself, though there is a lot of anger inside him. It ends up in his work, in his comic book adventures of Mr. Natural and Devil Girl and the sketches and one-offs he fills into notebook after notebook. One thing that Zwigoff succeeds at with smashing success in Crumb is relaying the subject and timbre of Crumb's comics to the audience. I had only a passing knowledge of the artist when I saw Crumb on its original theatrical release, but watching the film made me feel like I knew the work intimately. Zwigoff does this by just putting the camera lens up to the page and tracking the comic book panels as the artist tells the story behind them or sometimes even just reads the dialogue. The director also peers over the artist's soldier while he sketches in public. It's an unbelievable record of a craftsman at work. (Criterion also does a great job of giving us access to the work of all the artists, filling the interior booklet with efforts from all the brothers and even Robert's son Jesse, as well as giving us a full reproduction of a correspondence school's artist test Robert talks about in the film.)

R. Crumb's rendering of his childhood.

The comics of R. Crumb are known for their sexual deviancy and anarchic humor, and the creator makes no attempt to hide his fetishes. There is one hilarious scene where the artist poses for a layout in the porn magazine Leg Show, and the editor who set it up, who also happens to be a former girlfriend of Crumb's, hires models that fit his particular bill: thick legs, big butts, and a frame sturdy enough to give him a piggyback ride. In an effort to puzzle out R. Crumb's work, Zwigoff even gives some screen time to his critics. There are cases to be made for misogyny and racism in his comics, ones that Crumb ultimately seems to suggest are unfounded, but Zwigoff lets the detractors have their say all the same.

I think Crumb makes the strongest case for the value of his work himself when he says, essentially, these thoughts had to go somewhere, so why not channel them into art. If you consider what the other Crumb brothers got up to, the notion bears truth. Maybe if Maxon had put his peccadilloes onto more canvases, he wouldn't have gotten into legal hot water for harassing women. Maybe if Charles kept drawing, he'd have found a way to sort out the wrinkles in his own brain. Those are big what-ifs, their illnesses may have gotten the better of them either way, but you still have to wonder.

Because contrary to all the weirdness, Crumb does have some hope and normalcy. Both of Robert Crumb's children, Sophie and Jesse, were burgeoning artists at the time of filming, and Zwigoff shows the father sharing in his children's creations, offering advice and support. Somehow, this new generation appears to be turning out all right despite being a product of the same mad genius. As any creative person will tell you, making our art keeps us from losing our minds. Personally, if I get away from writing for more than a couple of days, my brain doesn't work right. In the case of the Crumbs, the family that draws together, stays sane together.

Visit the official R. Crumb website.

No comments:

Post a Comment