I decided I wanted to do a little homework before my planned second excursion to Scorsese's Shutter Island. Marty has said that Samuel Fuller's Shock Corridor, along with Jacques Tourneur's Out of the Past

Fuller was a triple threat on Shock Corridor. He wrote, directed, and produced. It's almost too bad he didn't cast himself as one of the patients, too. I'd have loved to see him wandering the halls, chomping on his cigar. He could have played a guy who believed he was a moviemaker, stuck in the hospital trying to get the inmates to hit their marks. In Fuller's stead, the main character of the movie is, after a fashion, choreographing his own drama. Peter Breck plays Johnny Barrett, a newspaper reporter who has taken a crash course in mental illness in hopes of convincing the courts that he is crazy. He wants to get committed so he can find out who killed a patient in the hospital. Like a demented game of Clue

Johnny pretends that he is a fetishist in love with his sister. The role of his sis' is filled by Johnny's girlfriend, Cathy, a stripper played by Constance Towers, who was also in Fuller's The Naked Kiss. Cathy sees the oncoming train before anyone else. Johnny and his editor (William Zuckert) only envision the accolades, they don't imagine any possible pitfalls. Cathy may sell her body for a song, but Johnny is going to sell his mind for prestige. Once inside, he must find the three men who witnessed Sloan being knifed. He will befriend each of them, linger about until they have an episode of lucidity, and then find out what they saw.

The interior of the mental hospital may be off-balance, but Fuller isn't using the setting for exploitative means. On the contrary, the facility in Shock Corridor is meant to be a microcosm of the outside world. Fuller saw the whole of society as participants in a collective madness, and each of Johnny's witnesses will expose not just a clue in Sloan's killing, but also one of the symptoms of the public illness.

The first man, Stuart (James Best), has been incarcerated since he returned home from the Korean War. There, he was captured by the enemy, and the Russians indoctrinated him into Communism. As Stuart tells Johnny, all while growing up, he was served hate for breakfast and ignorance for supper, and the Reds were the first to offer him someplace where he belonged. It's only when another American reminded Stuart of the Communist atrocities that he rejected his new philosophy. Too late, though, to keep him from being branded a Red. He suffered a psychotic break, retreating into a delusion where he was a Confederate general. It's a meaningful choice. He is embracing a despicable point of view that was not only once commonplace in American life, but that many also believe to have been unfairly vilified. (Let's not forget some people sport the Confederate flag to this day.) It's the same way some people felt about Communism, and if his family and countrymen weren't going to accept Stuart's ideas, he would retreat deep down into theirs.

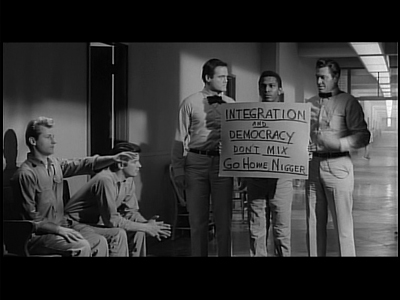

The second man is Trent (Hari Rhodes). Trent was the first black student admitted into a white Southern college as part of desegregation. The pressure to succeed in the face of the hate and persecution heaped upon him caused Trent to snap. In the hospital, he believes he is a Klansman. He steals pillowcases to make hoods, and he chases other black patients in the hallways shouting, "There's one of 'em now! Let's get 'im before he marries my daughter!" Like Stuart, something in Trent's subconscious decided if he couldn't beat the enemy, he would join them. As Fuller saw it, racism was a contagious disease that preyed on the minds of otherwise smart individuals.*

The third man is Dr. Menkin (Paul Dubov), who at one time was a nuclear scientist working in the arms and space races. Slowly, Menkin realized that he was part of a system of institutionalized death. Everything they were doing in the name of "science" was really just to kill the other guy faster than he could kill us. Rather than face the continued horror, Menkin regressed to the mentality of a six-year-old. A child knows no death, only happiness. In that state, Menkin can no longer destroy, he can only create. He spends his days drawing.

Menkin is the one who finally tells Johnny the identity of the killer, but it's also at the same time that Johnny loses his mind. While they had been talking, Menkin was drawing Johnny's portrait, and when the doctor shows the journalist his work, Johnny freaks out. Whatever is on that paper is something he doesn't recognize. Menkin says he has only drawn what he has seen. Symbolically, then, Johnny is being made to face all the wrong that he has accepted in the world. Worse, by going along with the patient's delusions in order to serve his own selfish goals, he has even been a participant. He's no better than the man who is always there, sitting silently with his arm raised in a kind of Nazi salute. This is the man Johnny can--and will--become. Ironically, just when Johnny is ready to speak up, his voice starts giving out on him. A mental block shuts him down at the most inopportune times.

Fuller made a rather smart choice to not visually portray the madness on screen. We never look through the eyes of the insane. There are no fish-eye lenses, nor leering hallucinations. Everything is through Johnny's eyes, the only exceptions being color sequences that show us dreams that Trent and Stuart are describing, some of it footage from an unfinished movie Fuller wanted to shoot in the Amazon (later described in the documentary Tigrero

Otherwise, any hallucinations we experience are Johnny's. Specifically, we see his strange dreams about Cathy. Does he really have a touch of the perversion that he pretends to suffer from? It seems to me that Fuller is using cinematic representations of women to make further commentary on societal imbalance. At the time he was making these low-budget productions, a little sex was good for getting your movie on the drive-in circuit. By making Cathy a stripper, Fuller seems to be relenting, but "I Want Somebody to Love," the sad song she sings during her bump and grind, works in opposition to the vulgar dance she performs [watch it on YouTube]. Johnny claims some kind of moral opposition to her chosen field, but he only ever fantasizes about her wearing her showgirl outfit. As punishment, Fuller humorously has Johnny attacked by a gang of feral nymphomaniacs in the hospital. It's like he's saying, "You wanted sex, here's more than you can handle." It's no coincidence either that the killer stabbed Sloan because Sloan knew he had been taking sexual advantage of the patients.

The director saves his biggest portrayal of madness for when Johnny finally goes over the edge. In a famous sequence, he floods the hallways of his hospital, creating a storm inside the building to match the storm inside the reporter's brain. It's Shakespearian in execution. Lear raged against the squall when his grip on reality was slipping, and water is significant in Hamlet, as well. The Danish Prince also feigned mental illness to solve a murder, and his lover was collateral damage. The doctors in Shock Corridor replicate the elements to batter their patients into some kind of complacency. They lock them in bathtubs and call it hydrotherapy, and shock treatment is like being struck by lightning.

I don't recall any direct visual parallels between Shock Corridor and Shutter Island. The isolation of the setting is a gimme in any story of this type, and the fact that Scorsese's hospital was surrounded by water is more coincidence than anything. (Really, Dennis Lehane chose the island setting for his novel

* One interesting racial element that was in Dennis Lehane's Shutter Island novel that Scorsese did not use in his movie was the racist prison warden, who at one point tells the story's protagonist, Teddy, via a measured rant laced with the N-word, that it's all the people who can be labeled with that word that is bringing the country down. He notes that just because Teddy is white doesn't mean he's not one of "them," as well. Teddy then uses that racism as leverage with some orderlies, basically asking them, "Who are you gonna serve?"

2 comments:

This is what I remember the film. SHOCK CORRIDOR's plot is based on a true, and famous, depression era story of a reporter going inside an asylum to write an expose. It was filmed previously as BEHIND LOCKED DOORS (1948)dir by Budd Boetticher, written by NAKED CITY writer Malvin Wald. Not that good as I remember.

When I mentioned to Fuller about the earlier film, he didnt recognize the film, albeit he was older and wasnt paying much attention to the question.

Malvin Wald said his script and the film were based on this well known story and thought Fuller may of seen it. I doubt it. I think we have two different interpretations on the same story, and SHOCK CORRIDOR is not derivative of the earlier film.

eric chavkin

Thanks, Eric!

I have seen Behind Locked Doors, and it does have a similar premise. I liked it more than you, but Fuller's film has more depth.

From a boxed set review I wrote in 2006:

* Behind Locked Doors (62 min. - 1948): This short feature directed by Oscar "Budd" Boetticher (The Cimarron Kid) doesn't spend any time fooling around. Airtight and quickly paced, Behind Locked Doors is a private detective story set inside a high-priced sanitarium. Prefiguring Sam Fuller's Shock Corridor by fifteen years, rookie shamus Ross Stewart (Richard Carlson, It Came From Outer Space) is enlisted by enterprising newspaper woman Kathy Lawrence (Lucille Bremer, Meet Me in St. Louis) to check himself into the loony bin. She has a lead that a corrupt judge (Herbert Heyes, Park Row) is hiding there to avoid arrest. Once inside, Stewart is instantly in over his head. Between the patients and the quirks of their conditions and a sadistic orderly (Douglas Fowley), it's not as easy to get around the hospital as he would have thought. In particular, he can't make his way into the locked ward, which houses violent patients like the Champ, played by Tor Johnson from Plan 9 From Outer Space.

Writers Malvin Wald (The Naked City) and Eugene Ling (Shock) have every piece in place. While there are moments of strained credibility, they know exactly what they need to bring Behind Locked Doors to a harried climax. Every element of the hospital has been put there for a purpose, and it's a lot of fun to watch it all come together in a violent rush.

Post a Comment