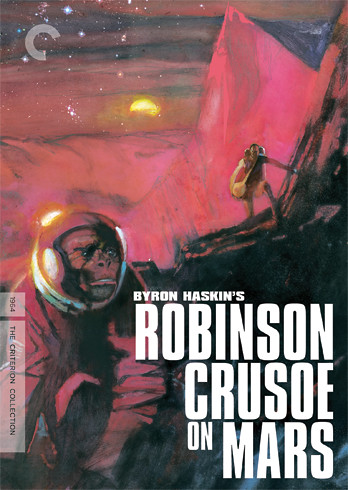

When Criterion announced earlier this week that they were selling some drool-worthy limited edition prints of some of their more illustration-driven covers, it seemed a good excuse to rummage through my shelves and pull out one of the featured movies that I had never seen before. This ruled out my choice for the print I would most like to have given the spare cash*, Jaime Hernandez's depiction of Divorce, Italian Style. It also disqualifies Amarcord, leaving the more sci-fi themed selections for me to choose from--a couple of movies still in the Monsters & Madmen boxed set and Byron Haskin's 1964 special effects adventure, Robinson Crusoe on Mars.

Robinson Crusoe on Mars is exactly what it sounds like, a fun re-imagining of the Daniel Defoe novel

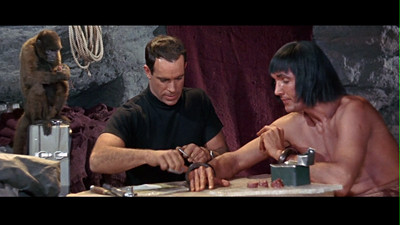

For the first half of the picture, it's just Kit and Mona learning to survive. They must figure out how to produce heat, where to find food and water, and how to keep breathing in the low-grade Martian atmosphere. Kit builds a camp, records his thoughts, and generally does whatever he can to keep from going crazy. The second half of Robinson Crusoe on Mars involves Kit discovering he is not alone. A malevolent alien race is mining the planet, using humanoid slaves they've captured on a world somewhere in Orion's Belt. Kit ends up helping one of the slaves escape, and in an open nod to the Crusoe story, he names him Friday (Victor Lundin). They become friends, and when the slave-owning aliens return to pick up their lost property, the trio of men and monkey make a run through underground canals and across perilous deserts to reach the polar ice caps.

There is no great storytelling innovation in terms of the well-worn Defoe narrative. In fact, from what I know of the original, I think they may have shaved a little of the deeper meaning out of it when they shot it into outer orbit. The alien Friday being white definitely softens the whole "brotherhood" aspect of the story, while the unspecified reason for the Earthmen's visit to space means there isn't any discussion of colonialism. A very basic religious message arises as both men move toward the middle to find some common understanding, but that is about it.

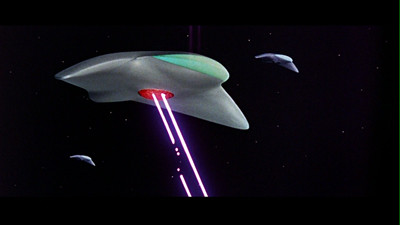

What has replaced the larger social meaning is Haskin's unrestrained imagination. Using a combination of models, traditional animation, and life-sized sets, Haskin creates the illusion of space travel and Mars in jaw-dropping detail. Though arguably coming off a bit kitsch now that more than forty years of moviemaking have passed, even compared to today's computer generated graphics, the scope of Haskin's inventiveness is pretty much impossible to miss. It fills every inch of every frame. Tubes of paste simulating steak and onions, oxygen-producing coal, and loin-clothed slave aliens that look like they are ready to start building the pyramids--no cliché of early space-race sci-fi is left unturned. Yet, once you surrender to the fun and wonder that Haskin intended to inspire, there is no going back. I was pretty much hooked as soon as I saw the monkey in a spacesuit clinging to the spaceship wall like he was floating in zero gravity. When haven't boys been suckers for monkeys?

Not being a sci-fi connoisseur, I'm not exactly sure whether to classify Robinson Crusoe on Mars as surprisingly progressive or charmingly naïve. Haskin's view of the future seems rooted in the same safe and clean predictions that were being made in the movies of the 1950s, yet the mission of Draper and McReady, as well as their monkey sidekick, does show a knowledge of the space race. Regardless of whether the vision of the future was progressive or not, the cinematic realization of it was, and Haskin's effects-heavy Robinson Crusoe is lively, colorful, and meticulous. I am sure many a budding filmmaker watched this film and saw a vast horizon of possibilities opening up, and the movie likely endures because it still inspires such awe.

This makes comics artist Bill Sienkiewicz an equally inspired choice to provide cover art for Robinson Crusoe on Mars. Sienkiewicz entered the mainstream comics scene in the mid-1980s, when I was an adolescent reading my first comics. Though his early work displayed a realism inspired by Neal Adams and Daredevil-era Frank Miller, Sienkiewicz quickly switched up his style. When he was assigned to the X-Men spin-off The New Mutants

I am not afraid to admit, I hated Sienkiewicz's work when I first saw it, just as I hated most experimental comic art at the time. My puny brain was not yet developed enough to understand it. Yet, there was something about his work that made it hard to turn away from, and when he collaborated with Frank Miller on Daredevil: Love and War

Which is not dissimilar to what Byron Haskin was doing with the Saturday matinee sci-fi film. He was taking an accepted sci-fi style and at once retrograding it by slipping it in the familiar loincloth of Robinson Crusoe and shoving it forward by using abstracted effects and radical visual ideas to create a more immersive reality.

For those who may be more interested in Bill Sienkiewicz, Image Comics just recently republished his masterwork. Stray Toasters

* If I was really sporting some disposable cash, I would actually buy the original artwork from the other Pietro Germi film in the Criterion library. My buddy Mike Allred has all of his drawings for Seduced and Abandoned on sale through his art dealer, Got Super Powers. A bargain at half the price.

1 comment:

Thought you might be interested in an interview I did with Efe Cakarel of The Auteurs and their partnership with Criterion.com

http://www.cinevegas.com/blog/?p=687

Post a Comment