The actor Richard Widmark passed away this week at the age of 93. It's a hell of an age to reach, and a hell of a life to live. He appeared in his first film in 1947, and his last in 1991 (not counting voiceover work a year later), racking up 75 on-screen credits. No small accomplishment.

His debut role as sadistic sociopath Tommy Udo in Henry Hathaway's Kiss of Death

This sense of completeness was something Widmark was also able to take to roles that deviated slightly from the good guy/bad guy norm.

The actor teamed with writer/director Samuel Fuller for the first time in 1953 for the pickpocket broiler Pickup on South Street. In the film, Widmark plays Skip McCoy, a "cannon" with the lightest fingers in the city. Having been released from his third extended prison stay just the week before, Skip is back on the subways digging through ladies' purses, risking a dreaded fourth conviction that could send him up the river for life.

On the particular morning when the film begins (and the whole story plays out over 24 hours), Skip picks the wrong mark on the commuter train. Candy (Jean Peters) doesn't see him lift her wallet, but the federal agents trailing her do. The girl is a patsy for some communist hoods, and she is unwittingly delivering microfilm exposing U.S. secrets. Skip doesn't realize what he has is so valuable until he becomes the most popular guy in town. The police are ready to make him an incredible deal for fessing up and handing it over, and Candy comes around offering cash, still clueless herself about whom she is working for. Putting the pieces together, Skip sees a big payday on his horizon.

Skip McCoy is the quintessential iconoclast, and probably as much representative of Fuller's own disregard for some of the go-along-get-along aspects of the Hollywood system as anything else. The petty thief stands for nothing or no one, just for himself. The law wants him to hand over the film in the name of patriotism ("Are you waving the flag at me?" he laughs), and though he doesn't like commies, he doesn't see why they can't do business ("So you're a Red, who cares? Your money's as good as anybody else's."). Neither system of beliefs is his. Capitalism hasn't done him any favors, and he has no reason to believe communism will either. If the cops could make him a counter offer he could trust, Skip would forego the $25K he's asking from the crooks, but money is at least something he can count on, not the fickle promises of lawmen on the make.

The best scene for showing what kind of a guy Skip is, actually, is when he finds Candy searching his riverside shack for her goods. He hasn't yet realized that she's a woman when he clocks her in the jaw, but once the lights are on and consciousness regained, he massages her bruised cheek with the same hand that turned it black and blue, loosening her lips and getting her to talk. He then only admits he knows she is lying after she kisses him. Skip sees the angles, and he's going to play then, and such nonchalant braggadocio is everything a classic Fuller rogue is about. Pickup on South Street is as rough hewn as any of Fuller's pictures. The climactic subway brawl is brutal and dangerous, and it should make you flinch more than once.

Yet, the movie also has some of Fuller's most tender writing. The deathbed speech Thelma Ritter's Moe gives when the dirty red bastard Joey (Richard Kiley) is threatening her is full of wonderful proclamations about what it means to stand by your principles, and the fact that Fuller turns the camera away when Moe gets it tells you how much affection he must have had for her. Ritter was nominated for a supporting actress Oscar for this role, and it is one of those supporting parts that is so important to the film, you can't imagine anyone else having fulfilled the duties. It's not just Moe's murder that convinces Skip to take action, but her words, as well. "Even in our crummy line of business," she tells him, "you gotta draw the line somewhere."

For Skip, that line is just like everything else: personal. Messing with Moe, putting Candy in the hospital when she stuck her neck out for him, that's messing with things that actually matter, with people Skip has come to count on. Thus, the resolution remains personal, too, with Skip taking care of business his own way. No cops, no money, just retribution.

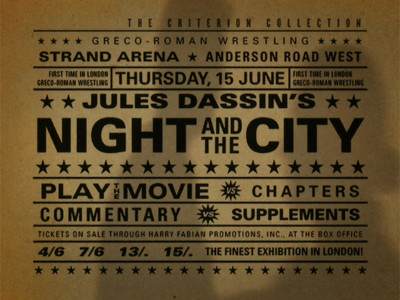

While Skip may have all the answers covered, three years earlier in Jules Dassin's 1950 noir Night & the City, Richard Widmark plays a character so close to the end of the rope, he's run out of questions, much less the answers. Harry Fabian is the kind of guy who can't see the breaks coming, so he tries to make them and blames others when they don't land in the right spot.

An American transplanted in London, Harry is a small-time hustler conning his visiting countrymen into going to the Silver Fox nightclub, where pretty girls shake them down for overpriced drinks, chocolates, and cigarettes. Harry's significant other, Mary (Gene Tierney), is also employed there as a singer. She's a loyal lover, accepting Harry's constant schemes with a heavy heart that results in a barren wallet. The owners of the Silver Fox offer a kind of warped mirror image to this couple: the husband, Philip (Francis L. Sullivan), is a successful--though sleazy--business man, but his wife Helen (Googie Withers) has no love for him. Phil and Mary are both being taken advantage of, except Phil sees his predicament well ahead of the coup de grace and he intends to turn the tables rather than be a cuckold.

Dassin and screenwriter Jo Eisenger's vision of the London underworld is reminiscent of The Threepenny Opera, with an intricate social structure that even includes a Beggar's Union. Harry is a walking joke in this world. He has the gift of the gab, but most of the regulars have long since tired of hearing his endless schilling. Like a film noir Fred Flinstone, he's had a million million-dollar ideas, none of which have panned out. His sales pitch is soaked through with flop sweat, and when he's not being brushed off, he's being laughed at. Widmark rides through the part as if he is on a roller coaster, confidence giving way to fear and anxiety, and then back to bravado again. He chews on every word, barely pausing to breathe, racing through Eisenger's lowlife poetry.

Eventually, Harry loads his hand with more cards than he can play. Convinced he can muscle into becoming a sports promoter, he tries to block the city's wrestling godfather, Kristo (Herbert Lom), by using the gangster's champion father (Stanislaus Zbyszko) against him. To fund this operation, Harry takes money from Helen that she wants him to parlay into her own nightclub using matching funds from her husband. Not knowing that Philip is wise to him, Harry isn't even aware of his own failure to shore up the foundation of this house of cards. Once a loser, always a loser, the odds are never in his favor.

Max Greene's moody photography serves to express Harry's doom. The encroaching shadows signal the death that approaches, and Widmark gets more frenzied and feverish, trying to help Harry weasel out of the darkness. There is nowhere for him to turn, the world he has insisted has been against him all along finally gives in to the base impulses he would foist upon it. Through much of the film, Dassin and Greene take their camera on the London streets, shooting Piccadilly Circus the same way Dassin shot New York for The Naked City. In the climax, we see Harry running across construction sites that look like ruins, disappearing in the mist, trapped on the streets where he earned his living.

Nowhere does this shooting style serve Night & the City better, though, than Harry's inglorious end. As morning approaches, Harry is calm for the first time, having accepted his fate and deciding to stop scrounging. Down at the water, Dassin shows a bridge in the distance, criminal assassins gathering, running back and forth like ants digging out a new farm. Seeing a chance to do right by Mary, Harry commits his first unselfish act by running into his undoing. It's a powerful scene, with Widmark sprinting at the camera, screaming, arms flailing, simultaneously possessed by the fear of death and running bravely into it. Forget any cool screen persona, that's true acting.

No comments:

Post a Comment