"Sixsmith wrings sweat from his handkerchief. 'I saw Charade with my niece at an art-house cinema last year. Was that Hitchcock? She strong-arms me into seeing these things, to prevent me from growing "square." I rather enjoyed it, but my niece said Audrey Hepburn was a "bubblehead." Delicious word.'

'Charade's the one where the plot swings on the stamps?'

'A contrived puzzle, yes, but all thrillers would wither without contrivance.'"

- from Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

I have to admit, I didn't like Charade the first time I saw it. Advance expectation is a killer of many a good film, and I originally watched the 1963 movie as part of my crawl through the Audrey Hepburn filmography. Being the oft-delayed coupling of Ms Hepburn and Mr. Cary Grant, I went in expecting a lighthearted romantic comedy--which is what I got, at least for half of Charade. The other half, as it turned out, was a Hithcockian thriller with a dark, even violent streak. In my mind, the two clashed in ways I couldn't quite reconcile. Who got all this blood in my peanut butter?

The screenplay for Charade, written by Peter Stone, is a study in incongruities. Mrs. Regina Lampert (Hepburn) and Mr. Peter Joshua (Grant) meet at a mountain resort, trade a few cynical retorts about love and their failed marriages, and essentially start a flirtation in a manner classic to the genre. Like two superheroes meeting for the first time who have to fight before they get along, two lovers in romantic comedies begin swapping acid before they swap spit, and the pleasure comes from watching their defenses crumble. For quite a while, the first words Reggie and Peter exchange were my answering machine's outgoing message. "I already know an awful lot of people and until one of them dies I couldn't possibly meet anyone else." "Well, if anyone goes on the critical list, let me know."

Upon returning to Paris, however, romance is not in the air, mystery is. Regina discovers her apartment empty except for a French police inspector (Jacques Marin). He informs her that her husband sold all of their furniture, absconded with the $250,000 he got for it, and then got himself thrown off a train. The money did not get thrown with him, and it is presumed stolen or missing. When three cartoonish crooks (James Coburn, George Kennedy, and Ned Glass) show up for the late Mr. Lampert's funeral, it becomes clear that it's the latter. In fact, not only are these guys looking for it, but so is the C.I.A. An agent by the name of Bartholomew (Walter Matthau) tells Reggie that her husband was not who he said he was, and that the $250,000 was actually stolen from the U.S. government by the dead man and his army buddies back in WWII. The bad guys will kill her to find it, and the U.S. will basically put her on the hook for it if she doesn't find the dough and return it. There are an awful lot of rocks to get caught between when the world is one big hard place.

Enter Cary Grant to save the day, right? Well, kind of. While Peter does offer to lend a hand, he may not be who he says he is. In fact, he may not be multiple people he says he is. So, while he romances Regina, we never know whose side he's really on, nor if he's the one responsible for all the bodies that are starting to pile up around them.

There is much for fans of classic romance to catch the vapors over in Charade. Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant have a marvelous natural rapport, and the scenes where they just clown around with each other are priceless. Director Stanley Donen has a graceful comic touch, and he gives his stars ample opportunity to do what they do best. A walk along the Seine, with its self-referential jokes about An American in Paris [review], which starred Donen's former creative partner Gene Kelly, is a wonderful display of comedic timing. As soon as Peter responds to one thread of conversation, Reggie switches to another, leaving the befuddled man to constantly catch up. The self-effacing charm that always served Cary Grant is well honed at this point, and the actor not only weathers jokes about his age, but requested them in order not to look like an old lecher chasing a young gamine through the City of Lights. These get some of the best laughs in the movie. (If only someone had taken the air out of Gary Cooper's tires in the same way before he courted the young actress in Love in the Afternoon

Yet, there is also some squeamish violence to contend with in the plot. Despite Lampert's old army buddies being overdrawn caricatures--Coburn the boorish Texan, Glass a nebbish, Kennedy a one-handed monster--when they go to work, Donen doesn't soften any of their blows. When they confront Reggie alone, there is a real feeling of sexual threat, and when they engage in fisticuffs with Peter, the violence is deadly. A rooftop tussle with the hook-handed Kennedy leaves a big, bleeding gash on Peter's back, and when the crooks start getting themselves killed, the manner of the murders is uniformly gruesome, escalating to James Coburn being trussed up with a clear plastic bag over his head, the death grimace of his suffocation visible through the Ziploc.

The sweet stuff was so sweet and the bitter business so bitter, I couldn't make sense of why Donen and Stone had chose to put them together in this way. Was it just the changing times, a need to update and compete? Probably not. Though change was a-coming, the censorship boards had not yet gone completely lax, and the violent turnaround of American movies was a couple of years off. While Charade was maybe testing those waters, it wasn't done out of competition, but a deeper thematic concern.

Charade is a tapestry of lies that extends beyond assumed identities and crime. In this narrative, relationships have also become charades. The Lamperts are in an empty marriage that is only saved from divorce by the husband's untimely death. As it turns out, the wife didn't know her husband at all, and what she is discovering is that love is not as simple as it once was. Can we really know anybody? Is courtship anything more than donning a mask to convince the person we desire that we are someone to be desired, as well?

Even beyond that, though, moviemaking is a charade. For decades, the audience had been conditioned to view thrillers and romantic comedies alike without considering that any real-life equivalent of these fictions would carry with it real-life consequences. In a manner that could be just as startling as anything coming out of 1960s France and the British Kitchen Sink school, or still to come with the young turks of new American cinema, Stanley Donen was exposing the false bottom of the Hollywood technique. Realizing this gives new meaning to the climactic showdown, where the real killer chases Reggie into a traditional theatre and finds himself on the business end of a trapdoor. There is nothing under the stage, you see, the boards these players tread are not rock solid, and their actions are not to be believed. It's like the fake-out with the water pistol in the opening scenes, but played out for 114 minutes

This was the crucial logic that I missed in the cloud of my initial expectations for Charade, a mist that had to be cleared for me to see the film for what it really was. Once I figured out the reason for the juxtaposition of love and violence, comedy and crime, I could see the greater meaning the filmmakers were trying to convey. Charade is not a subversion of silver-screen romance, but an affirmation of it. Love isn't knowing exactly what you are getting, but extending a level of trust that tells the other person that he or she is worth the risk of being lied to. When the bullets are flying, Peter extends his hand to Reggie, and she asks why she should place his faith in him. He tells her there is no logical reason on Earth for her to do so, and he's right, there isn't. Thankfully, emotion is eschewing logic to follow instinct, and it means all the more that Reggie is able to love again when there is no good explanation for it. She simply follows her heart, and the charade dissolves.

Criterion has brought Charade to the Blu-Ray format with a new high-definition digital transfer, 1080p, at the original 1.85:1 aspect ratio. The restoration is impressive. Colors are excellent, with realistic skin tones and vibrant hues (pay special attention to the reds to see what I mean.) Their is a pleasant, natural grain to the overall image texture. It can sometimes make the picture look a little soft, especially in extreme close-ups, but not so you'd notice once you are caught up in the story. What is the most remarkable is the depth of field. Details are clear in complicated close quarters like the hotel rooms, and there is tremendous clarity when Cary Grant and George Kennedy are fighting on the rooftops. You can see the whole city behind them, and the neon signs glow with real electricity. In the subway, you can see the shine on the wall tiles contrasted with the texture of the cement floor. I have seen three or four different versions of Charade, and I swear, it's never looked like this.

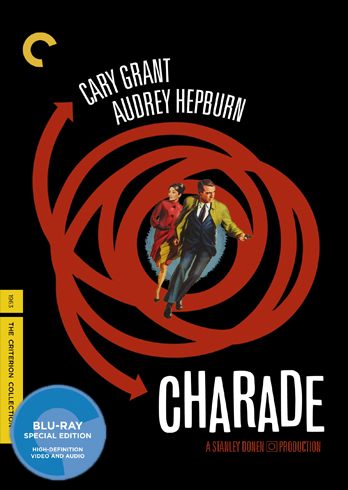

The BD of Charade comes in a similar package to the previous DVD releases, though with an improved cover image with a vintage movie poster design. The booklet inside is likely the same as the 2nd edition, reprinting the Bruce Eder essay that has been part of the deal since Criterion's first 1999 release. (I never did purchase the upgrade from a couple of years ago, so I am guessing a little.)

Also carried over is the excellent commentary with Stanley Donen and screenwriter Peter Stone. I love listening to Stanley Donen. He's just such a bright guy--in every sense of the word.

The original theatrical trailer is also included.

Missing from previous editions is the section showcasing the filmography of Stanley Donen, which was basically a text-based, illustrated biography. (The 1999 disc had a similar feature for Peter Stone that I believe was dropped from the later reissue.)

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

No comments:

Post a Comment