Anton Corbijn made a music video for Joy Division’s “Atmosphere” back in 1988 that, whether he intended it or not, is reminsicent of the opening scenes from Orson Welles’ masterful 1950s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Othello. Which is an odd way to enter into an old, whispery black-and-white film, thoughts of one of Ian Curtis’ most doomy and gloomy songs hanging out in the back of my brain, but such it is. Welles was goth before goth. The sequence is a flash-forward to a funeral, all pomp and dark circumstance. The slanted angles are ominous, and they let you know this is not right, this should not be happening. The quick zoom on Iago in his cage is urgent, furious, frustrated--you know immediately that he’s the villain. He did this. It’s a crazy smart way to set up a story that the filmmaker can presume everyone knows. Because now you’re intrigued. You want to know who is dead and how that evil dude got stuck in that jail.

This Othello may be the least stagey film adaptation of Shakespeare ever made. Infamous in Welles lore for being shot over three years, with Welles pausing production to rush off and take bit parts in other movies to raise cash, and then returning to Italy to resume his work. Just look at those scenes once the story proper begins. The camera moves up and over the different levels of Venice, from the canals to the windows on the upper floors, then down spiral stairs chasing an angry mob carrying torches. It’s all inertia, all movement, and at the same time, there are indications of class represented via each player’s position in the construct. Later, there are spectacular fights and chases below ground. The violence in this movie is invigorated with the chaos of its production. So much so, in fact, that sometimes, ingeniously, the dizzying pursuits hide how the disparate pieces, shot months and even years apart, are stitched together. Welles never loses the plot--neither figuratively nor literally.

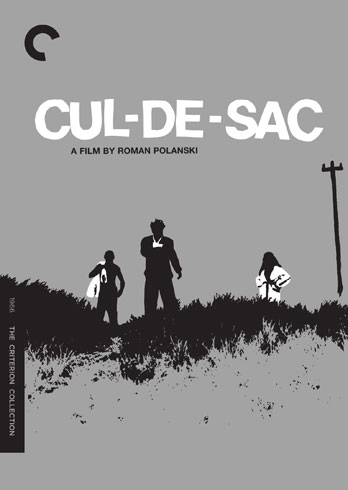

The balance of setting and the use of exterior vs. interior is also a reflection of the physical and the internal. Like in Roman Polanski’s Macbeth [review], the players are tiny in comparison to the architecture (though, I guess it should be that Polanski is like Welles). And to be fair, it’s petty concerns that set the tragedy of Othello in motion. For those who don’t know the story, Othello--played by Welles himself--is a general in the Venetian army. He is also a Moor--a term for Muslims living in the area in the middle ages--a fact that sets him apart from his comrades. When Othello elopes with Desdemona (Suzanne Cloutier), a politician’s daughter, eyebrows are raised. Othello’s lieutenant, the silver-tongued Iago (Micheál MacLiammóir), sees the opportunity for advancement and takes advantage of Othello’s position as an outsider, convincing him that Desdemona is cheating on him and setting everyone on a path of destruction.

Up until Welles made this film, the tradition was for white actors in the Othello role to wear blackface, a tradition Welles upholds--albeit not to the exaggerated fashion we tend to think of when we hear the term. The irony here is that despite such a regressive decision, Welles embraces the progressive subtext in the play. There is a fascinating racial commentary at work, particularly in how Othello and Desdemona defend their marriage to her father. And already, there is a suggestion that a black man must be even better than his white counterparts.

When we consider the dynamic between Othello and Desdemona, and the violent outcome of his suspicion, Shakespeare was ahead of his time in giving us a perfect portrait of toxic masculinity. Othello’s jealousy is fueled by pride. In his performance, Welles is deceptively two-note: repression of rage and rage. Yet, there is more to his control here; again, he is the black man who has to be better, who has to always show composure, even when the façade means he can’t have a reasonable discussion and ferret out the truth. As his foil, Iago is so matter-of-fact, eschewing the obvious mustache twirling and greasy machinations, pulling off his tricks by merely being present. There is a Zen koan about how water is the most powerful force in the known world because of how it gradually erodes rock; this is MacLiammóir’s Iago. His is not as sinister a performance as tends to be the norm with this, one of Shakespeare’s oiliest villains. MacLiammóir is more considered, passive-aggressive, almost as if he doesn’t care. There’s a hint of a sociopath in the portrayal, so little moves him.

While I am dazzled by the filmmaking overall, one downside of knowing Welles history and struggle is I am often too aware of his technique. My eyes drift from an actor to the artfully placed shadow on the wall, for instance, or to clock the depth of field, how close one element is and how far the other, seeing how expertly the shot was constructed. And, of course, there’s how many times you note that the dubbed voice of some bit player is Welles himself, making up for perceived bad performances or just poor sound due to shooting on the fly. I suppose this isn’t really that tough a problem to have. There’s so much virtuosity in Welles’ mis-en-scene, one should never become immune to it. Just look at the construction and the edits when Othello returns home after first being incepted by Iago. The quick cuts and askew angles pull the whole thing together with such emotional kineticism, it’s like watching Eddie Van Halen play classical music on his guitar; you can’t help but notice that human hands should not be able to create art in that way.

In that scene, and throughout the film, Welles’ montage is about scale vs. intimacy. When Othello and Desdemona go to their marriage bed, they are rendered as just shadows on the wall, but their shadows are huge. We are at once with them and outside, but the marriage consummation casts a pall over everything else. Interestingly Iago is more intimate with Othello than even his wife. The framing gets tighter the deeper we get into his machinations. When Othello and Iago make their sinister pact, the close-ups are so tight, their conversation can’t even share a frame, they are too large within their individual screens. Then the next deal is made in a sauna, arguably a place where all are vulnerable, and where trust is meant to be at the utmost. I mean, where else do you go and get naked and perfectly relaxed around total strangers? (Answers neither requested nor required.)

It’s of no small significance that it’s in the sauna where Iago actually resorts to murder himself. Welles lights his eyes almost as if to give him a supervillain mask...or to suggest he’s enlightened? I mean, Iago has a curly white dog years ahead of James Bond villains popularizing cats, and decades ahead of Paris Hilton and other modern social scoundrels carrying around their pooches in purses. It also feels like 1950s shorthand for homosexuality, which could suggest much about Iago’s true motivations were we to take that onboard. His own love of Othello is even more forbidden than Othello’s love for Desdemona.

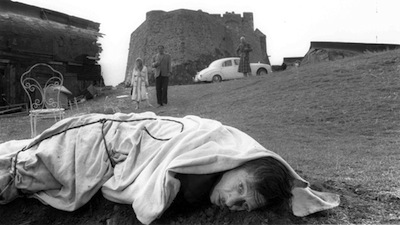

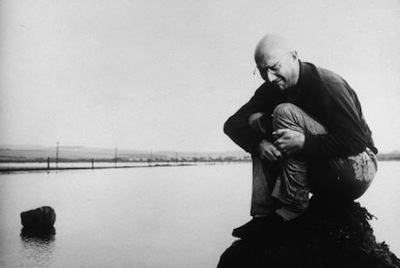

The most intimate moment in Welles’ Othello, however, is also the most harrowing: the murder of Desdemona. The sheet Othello wraps over her face inadvertently highlights her whiteness, an intentional emphasis on her innocence, but also a horrific reminder of how black men are portrayed in the media. The last kiss between them, passed through the death shroud, appears more to suck out her final breath than connect her with her homicidal husband. It’s legitimately uncomfortable to watch. Immediately after, Othello imprisons himself, locking the door to their chambers, speaking to the crowd through bars--Welles visually shows his guilt before the character is ready to admit it. Or to modern eyes, we can divine that he knows this is the fate society has always imagined for him...

...and if there’s one thing Shakespeare’s tragic figures can’t escape, it’s fate.