Roman Polanski's 1966 film Cul-de-sac is a darkly comic genre send-up, playfully toying with B-movie conventions while subverting them with Polanski's impish humor. It's like a Peckinpah's Straw Dogs [review] crossed with the old Bogart picture The Desperate Hours

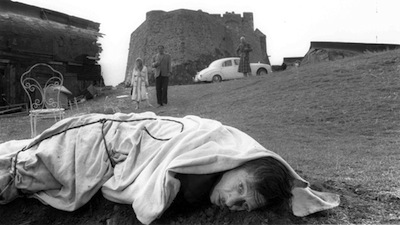

The film opens with two gangsters on the lam in Northern England. A botched job has left the British crook Albie (Jack MacGowan) with a shotgun blast to the gut and his brutish American cohort Dickie (Lionel Stander) with a useless arm. When their stolen car dies in the middle of nowhere, Dickie goes searching for help. The only place for miles is an 11th-century mansion on a hill that looks down on the sea. The residents of this out-of-the-way villa are George (Donald Pleasance), an older war vet, and his young French wife, Teresa (Francoise Dorléac). On his way up the hill, Dickie spies Teresa rolling naked in the sand with a neighbor boy, leading him to draw certain conclusions about her, and his first encounter with the relative newlyweds as a couple in the dead of night interrupts their bedroom playtime. They were goofing around, and George is wearing Teresa's nightgown and he let her put make-up on his face. What was a joke becomes a defining factor in the relationship between the fugitive and his hostages. The burly thug is a true man, and George is his bitch.

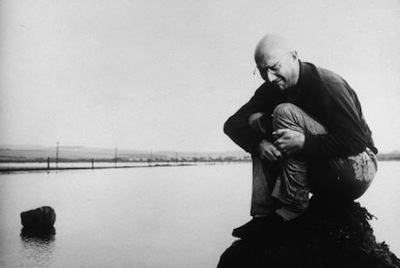

Cul-de-sac plays out over 24 hours, as Dickie waits for his London bosses to pick him up from the isolated locale. The tide comes in shortly after the car stalls, stranding Albie up to his chest in water, and the only way in and out that night is by boat. George caves to the imprisonment, stoking already existing tensions between him and his wife. Eager for the attention of a real man, and determined to start a fight between her husband and their captor, Teresa spends the night drinking homemade vodka with the bad guy, who is, let's be honest, charismatic and gregarious despite his rather abusive nature and poor career choices. This is likely intentional. Polanski--who co-wrote the script with Gérard Brach--is forcing us to like the person that is supposed to be the least likeable one the trio. Teresa is manipulative and dishonest, and George is spineless and fawning. It's not just that he won't stand up to Dickie--who never even really has to pull his gun--but we know that George also kowtows to his wife. Pleasance plays George as slimy and mercurial, physically shrinking from just about any human action. He would have made an excellent Igor to any number of cinematic Dr. Frankensteins.

Roman Polanski can be a polarizing figure, and Cul-de-sac would do little to discourage any viewer that has previously taken issue with his approach to gender divides. Teresa's desire to be dominated by a "real" man and her sexualized behavior (she flirts with almost every male character in the film, and it's to Francoise Dorléac's supreme credit that she somehow makes this woman appear deeper than the writing), and George's cross-dressing buffoonery are certainly provocative elements of an intentionally provocative film. Throughout Dickie's stay on the island, the social order keeps changing. He goes from being drinking buddies with Teresa to climbing in his cups with George, and come morning, the whole dynamic gets upended when George's relatives pay an unexpected visit. Teresa sees an opportunity to take control, and she basically introduces Dickie as their servant. This injects class concerns into the mix, a poisonous stew stirred up further by how the family treats George. I think this lends credence to the argument that Polanski isn't adopting any particular point of view, nor is there a pronounced macho agenda; rather, he is using a familiar hothouse scenario to apply stress to his characters' lives and watch how they react. Ultimately, the plot of Cul-de-sac is a pressure cooker that scorches them all. Anyone expecting good guys or bad guys or any last-minute rescue or triumph is probably right to expect these things under the rules of ordinary crime movies, but Cul-de-sac is not cut from those trappings.

I would contend that the conflicts portrayed in Polanski movies also extend to his aesthetic approach. His movies are at once meticulous and sloppy, tightly wound but also fraying at the edges. Cul-de-sac is a smartly planned drama, with an elegant plot structure and carefully arranged framing, but there is always a little bit of anarchy, be it a blunt editing choice or slapdash overdubbing or a sudden camera move that throws the visual rhythm into disarray. Breakfast with George's family begins as a well-choreographed tableau of social manners and interpersonal rigidity, but the sudden introduction of a shotgun creates a narrative panic. To capture the spontaneous frenzy, cinematographer Gilbert Taylor zooms in unnaturally close on each actor, distorting their features, and breaking the respectful spatial relationships that Polanski has established. The change-up appears almost haphazard and amateurish, but it perfectly illustrates the hysteria of the sequence. The unpredictable introduction of violence would disrupt our lives off screen, so why shouldn't it do so onscreen, as well?

The film eventually returns to its central three as the second night descends, with a climax that shows how far out of control they have gotten and the effects of further compromises and lines being crossed. It could be said that their true natures emerge, that George is a rat and Teresa is empty and Dickie's bluster can only blow for so long. None gets off lightly, regardless. The clash of ideals and wills and the resulting fallout is as natural and inevitable as the tide, which rolls back in on schedule, isolating those that remain even further. In most movies that deal in archetypes, we look for the one that most closely resembles our own nature; in a movie like Cul-de-sac, we leave hoping that we are none of them, and in the worst case scenario, fearing we just might be.

Criterion's Blu-Ray of Cul-de-sac gives viewers a high-definition 1080p image framed at a wide 1.66:1 aspect ratio. The black-and-white picture is sharply realized, with strong darks, lights, and nuanced shades of gray. Though the print still has some surface markings at times, usually in the form of slight scratches in the upper half of the frame, this is rare, and the overall resolution and clarity of image is fantastic, with a subtle grain that maintains the quality of the original film stock without being overly pronounced on modern television sets.

The soundtrack is mixed in mono, uncompressed. It sounds excellent, with full tones and no distortion. Some of the actors tend to mumble and this can be hard to make out, but the shifting volume levels suggest this is intentional, all part of Polanski's off-balance design. Likewise, the wonky Krysztof T. Komeda music takes an appropriate position in each scene, often ironically underscoring the action with his blending of odd electronic noises with more traditional melodies.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVD Talk.

No comments:

Post a Comment