Reiko did not flinch.

Her round eyes showed tension, as taut as the clang of a bell.

'I am ready,' she said. ‘I ask permission to accompany you.'"

Yukio Mishima's 1961 short story "Patriotism" is a vivid examination of ritual suicide and a staunch tribute to the resolve of his main characters. The young lieutenant in the Japanese Imperial Army chooses death rather than have to hunt down his friends and compatriots, men who, in service to the Emperor, staged a revolt against his poisonous advisers in February, 1936. 31 years of age, the lieutenant is a newlywed, having married the 23-year-old Reiko six months prior. Their short union has brought them intense passion as well as near-perfect bonding. From the start, the soldier prepared his spouse for the sad truth that a warrior's wife must follow him into death, and when the time comes, she accepts it without fail.

Even today, the level of detail the controversial Japanese writer unleashes in this tale is astonishing and disquieting. Small trinkets of their marriage home are described, as is the nature of their resolve, their intentions for how they will be found in death. Prior to committing seppuku, they enjoy one last night of lovemaking, and, unsurprisingly, they embrace each other with the gusto of lovers heading to their own graves, who know this will be their final coupling. Mishima describes this vigor in exacting prose, writing of every inch of their body, their every movement, with a erotically charged vocabulary. Sights, smells, the feeling of skin on skin--no sense is ignored. It is as arousing as the events that follow it are grisly.

In samurai films, when a warrior kills himself, he quickly cuts across his belly and falls over. At most, there is also a second who beheads him before he experiences too much agony. This is not the kind of easy death Mishima wishes to describe, because it is false and because there is no heroism in action that simple. Therefore, the lieutenant's self-disembowelment is described with the same level of detail as the sex. It's slow, painful, and requires tremendous determination of both the husband and the adoring wife who witnesses it. She must go after he does, left behind to prepare the house for those who discover them. Mishima gives her a quicker death, but no less brutal. Its swiftness is like a great, surging relief.

For Mishima, ritual suicide in service to Japan was an ultimate expression of one's love of country and representative of values that had been lost following WWII. The lieutenant's suicide note consists of five words: "Long live the imperial forces." There is no self-pity, no outpouring of emotion*. State what you mean to do, and act. To Mishima, this was strength, honor, and above all, patriotism.

Five years later, the author, whose previous film experience had been as lead actor in the crime picture Afraid to Die

The story in the 27-minute film follows the original short narrative exactly, though adhering to the social mores of 1966 in terms of what details can be shown. One way around this for Mishima is to stage the film as a classical Noh drama, placing his actors on a bare stage and shooting without dialogue. The backstory is explained on scrolls that appear as intertitles between each chapter. Decorating the room where the couple will spend their last night is one piece of decorative calligraphy, mentioned briefly in the short story, kanji spelling out the words "Wholehearted Sincerity." It's a constant reminder of their intentions.

Recasting the story in a traditional theatrical form gives Patriotism the noble air of historical pageant. Removing dialogue means that the action is all in gesture, adding further to the fact that the committing hara-kiri is also a gesture, an action instigated with a specific intention of effect. Since he can't show all the carnal detail of the sex between the lieutenant and Reiko, Mishima falls back on the greatest strength of his prose: his eye for detail. The lovemaking is shown entirely as close-cropped shots, the camera framing specific body parts, mainly focusing on the eyes, but also showing hands, tousled hair, the stomach, and boldly, Reiko's tender kisses on her husband's neck. Though the suicide is far more graphic, it is shot in the same way, with Mishima seeing that an image of clenched teeth or the splatter of gore on Reiko's kimono will carry home the emotional punch of the suicide while the viscera will illicit the required repulsion in the viewer. I was actually pretty surprised by how graphic the soldier's death was, the blade sliding across his abdomen, torrents of bloody flowing from the wound, and eventually his entrails spilling onto the floor.

Strangely, Mishima hides his eyes for most of this scene. Outside of the lovemaking, he is always in uniform, and he wears his hat so that the visor covers his eyes. I am not sure what this means as far as a stylistic choice**, but it echoes homoerotic and fetish imagery in a way that the sexually ambiguous author may or may not have intended. At the very least, it represents his own fetish-like obsession with ritual suicide, which we also see in the way Reiko briefly licks the blade of her dagger before plunging it into her throat.

The most poignant scenes of Patriotism are reserved for Reiko in the film, just as they are in the short story. Mishima allows us passage into her inner life far more than he lets us into the head of the lieutenant. The movie opens with her packing up her tiny animal figurines, each one reminding her of aspects of her life with her husband. The dreamy, superimposed images of his hands caressing her, as well as of a sacred shrine, brought to mind the surrealist shorts of Jean Cocteau. (Likewise, the use of traditional Japanese theatre brings to mind another Criterion release of a Japanese film about lovers taking their own lives, Masahiro Shinoda's Double Suicide.) It's as if she is forced to feel the loss for both of them, the kind of doubt and regret that the lieutenant's stoic sense of duty will not afford him. After his body has fallen, she fixes her make-up, settles the house, and then takes her life, falling on his body, the lovers ending in an embrace. Where his blood was dark on white walls, hers is white on black, her purity her strongest virtue. (Though, it also looks a little like semen, thus emphasizing the concept of sex and death, as exemplified in the two main acts of the film.)

The final shot of the dead couple shows them transported to a sandy rock garden, with the rakings of the gravel swirling around them in such a way that it looks like a giant fingerprint. I am a bit baffled by this, not sure if I am reading too much into it, but I am also intrigued by the possibility. Traditionally, the rock garden is a place of tranquility, also representing a vast sea of purity and peace. Had Mishima seen the other visual interpretations, even greater meaning could be gleaned from the choice. Could the artist be indicating that a greater fate has crushed these two under its giant thumb? Or is this the fingerprint of all humanity, the larger whole represented by the pair?

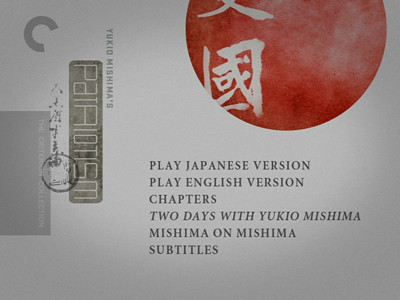

There is no denying that Yukio Mishima's Patriotism is an effective piece of cinema. Though I can't imagine all viewers will agree with his assertions about the nobility of taking one's own life as a philosophical gesture, for a provocateur as infamous as Mishima, his success comes from the fact that no one who watches his movie will be able to avoid a strong reaction of some kind. The emotion of the acting, risen to operatic levels by the shooting style and the orchestral score, along with the precise artistic choices of the sex/death montages make for a striking motion picture experience. With all of the great bonus features, the Criterion release of Patriotism also serves as a gateway into the larger tableau of Yukio Mishima's art. Dig through it all--the book, the interviews with Mishima on the disc, and the excellent new documentary reuniting surviving crew members--and you'll likely have your curiosity piqued sufficiently to desire more.

Criterion's release of Patriotism is timed to coincide with the their edition of Paul Schrader's biopic, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, which includes scenes about the making of this movie. A review of that film will follow shortly.

* One must wonder what Mishima would have made of The Fire Within.

** Actually, as the director reveals in his essay in the accompanying booklet, Mishima chose to do this to emphasize that the soldier was a creature of duty and little else, and thus he hid any gateway into the man's interior self from the audience. My initial reaction, though, is also bolstered by the same essay, where Mishima details the lengths he goes to in order to get the right details of the clothes. Or, really, by seeing photos of him that are out there that show him posing in leather next to a motorcycle, very Village People/Judas Priest.

No comments:

Post a Comment