A man walks through the desert, dressed in a pinstripe suit and a red baseball cap. He drinks his last swig of water out of a plastic jug and eyeballs the hawk that is eyeballing him. From the landscape, the endless swath of rocks that reaches back behind him and extends off into nothingness in front of him, we can tell that this is the American South. From the title of the movie, we know it's probably Texas, and even the most undereducated film fans will know that man is Harry Dean Stanton. He stands alone in a wasteland. Walking toward something, walking away from something else. Or perhaps like a shark, he is moving lest he die.

This is how Paris, Texas, the 1984 film from German director Wim Wenders and stalwart American playwright Sam Shepard, begins. It's a mysterious opening, befitting a film that is ostensibly a mystery. The central question of who this man is and why he is here is one we will be asking throughout the film's laconic 145-minute running time. Because it's Harry Dean Stanton, because it's Wenders and Shepard, we would probably wait even another two hours to get the answer if we had to. Paris, Texas is too good to look away from.

Stanton plays Travis, a man who has lost his way. He is the focal point of the mystery, but he is not its only facet. Travis has been missing for four years. From the look of his shoes, he may have been walking that whole time. He doesn't sleep, he barely eats. Right after he disappeared, his young son Hunter (Hunter Carson), then just about to turn 4, was dropped off at his uncle's house in California. Travis's brother Walt (Dean Stockwell) and his wife Anne (Aurore Clement) took him in. The boy's mother and Travis's young wife, Jane (Nastassja Kinski), eventually got in touch, but then she got out of touch again. Her only contact is depositing money in Hunter's bank account on the 5th of every month. Walt and Anne inquire after what happened, but Travis is not telling.

Paris, Texas is divided into two halves. The first begins with a road trip, with Walt driving out to pick up his brother in the isolated trailer park hospital where he has been taken after collapsing. They drive back to Los Angeles--Travis refuses to fly--and try to reacquaint Travis with the land of the living and with his son. The first glimpse we get of Jane is in Super 8 home movies Walt shot just before whatever went down went down, and they are so perfectly quaint and idyllic, so sharply contrasted to the vividly drawn realism of the main film, they resemble little more than fiction. That man sitting and watching himself on the screen was never really the man he is watching. That never happened.

The second half of Paris, Texas is Walt taking Hunter back to Texas to look for his mother in Houston and try to reclaim the life they saw on Super 8. It's also the life of the three people in a black-and-white photo booth strip, a memento Travis gives Hunter. He carries another photographic dream, a snapshot of a plot of land in Paris, Texas, that he has never seen but that he bought with the hope of moving his family there. He chose the spot because it's in the town where his mother and father first made love, and likely where he was conceived. The picture is just a vacant lot with a sign on it. The sign might as well say, "This is an illusion." Like father like son, Travis is chasing something false. His story about his parents is adorable and romantic at first, until later he reveals that his father's joke about meeting a woman from "Paris [pause, wait for it] Texas" was the kind of harmless lie that takes over a marriage and creates an alternate reality that the truth can never compete with.

Wim Wenders has an equally unreal love affair with America, one born out of Hollywood cinema. His affection for the wide-open spaces and dilapidated architecture of Nowhere, USA, is one that has little time for the economic desolation that has allowed these places to be rundown. He shoots his locations with a foreigner's eye, aided by his director of photography Robby Müller, a Dutch cameraman who also shot a lot Jim Jarmusch's tours through his own alternate America. Wenders and Müller work with a large frame, using the expansive terrain as a way to isolate their characters. Any man looks small standing in the center of the American frontier.

Yet, they also seem to have an idea of how unreal this dream is, and they bathe many scenes in unnatural colors. The nighttime skies are pink with pollution, and the cities are a neon green. It's a sickly palette, reflective of the inner nausea that is compelling Travis to retreat from personal contact.

Communication is often said to be the key to any relationship, and communication is all out of whack in Paris, Texas. When we first meet Travis, he refuses to talk, and the doctor who cares for him thinks he's a mute. (I am not sure if it's significant that this doctor, played by Bernhard Wicki, is a German in exile, or that Walt's wife Anne is a French immigrant--except that maybe she represents the real exotic love that is falsely evoked by the story about the brothers' parents. Amusingly, German-born Nastassja Kinski plays the love that has gotten Travis so twisted up as an authentic Texan.) It's as if Travis must learn to talk again the way he must learn to love again. Opening up is the first step to regaining his family.

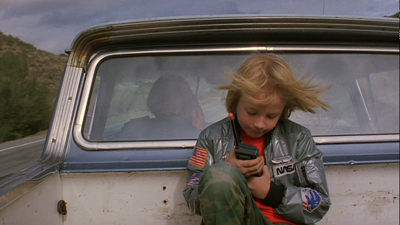

It's what Jane will eventually encourage him to do, though she won't know it's him at the time. They talk with a pane of one-way glass between them. He can see her, but she can't see him, and even then, Travis has to turn his back and talk to her. Two peas in a pod, she must do the same when she opens up. Earlier, even though Travis and his son are getting along, they default to chattering back and forth on walkie talkies, foreshadowing the emotional climax where Travis can only tell the boy how he really feels via tape recorder.

The details that went into Jane and Travis splitting are not as predictable or cut and dry as we would imagine. Both parties had a hand in things falling apart, though Travis reveals a heroic streak by taking full blame when explaining the gist of the problem to his boy. His journey has stirred up many things for himself and for the viewer. He represents grief, loneliness, and shame, but also love. Of all his sins, failing at love is the one that weighs heaviest. Loving each other should have been enough for Jane and Travis, and loving their child was the most important thing of all. Travis has been doing penance for these sins, and so has Jane. He finds her in a lurid limbo, stuck role-playing endless falsified versions of meaningful relationships. The building where she works even stands as a symbol of the believed promise of the American dream and the often sad reality of it. On one side, someone has painted a full-size mural of the Statue of Liberty; on the other, a brown-skinned woman, representing the people Manifest Destiny trampled, and also the ladies serving time inside those walls. Maybe I was too quick to judge. Maybe Wenders does see the dark underbelly of Americana after all. Sam Shepard certainly does, and Ry Cooder's bluesy score also provides Paris, Texas with some authentic roots.

Paris, Texas ends on what many would call a sad note, but it's the kind of ending I always find hope in. Travis has made things right, he has found a way to bring mother and child back together, but even in doing so, he has accepted that he is the one thing that can't be in their lives if they are to succeed. The attraction between himself and Jane will always have that heat, they will always burn each other (sometimes literally, as it turns out), and so better for him to extricate himself. Wenders' imagery when they are finally conversing even goes so far as to show us how they tend to swallow one another whole.

Harry Dean Stanton brings an inner nobility to the performance that allows Travis to be sympathetic even at his lowest moments. The actor has sad, soulful eyes. They express the glint of joy when Anne shows him affection or when he is bonding with Hunter, and they also show the poison of jealousy when his first reunion with Jane goes awry. Ironic, then, that his best moment comes when we can't see his face at all. The way he stands, the shape of his body, the damned aura of Harry Dean Stanton--they tell us everything. He stands in the emerald glow of an empty parking lot, watching over his son until he is sure his mother has come for him. Never mind that it would actually be impossible for him to see into Hunter's hotel window. Travis is the all-seeing father now, sacrificing himself for the good of those he cares for. It's a powerful finish, and though he may end Paris, Texas as alone as he began it, Travis has given everyone what they need to continue on, including himself. He has shed his illusions, and now he can make a new reality.

Comics artist Jen Wang once posted a piece of Paris, Texas fan art on one of her blogs. I saved it to my hard drive when she did. Like all of her stuff, it's lovely. Jen's first full-length graphic novel Koko Be Good is due this fall and guaranteed to be a must-read.

1 comment:

Jamie, very fine piece" question,Does the ending remind you of the ending of "The Searchers"?

Your noteing of Wemmer's romance with the American west, and the cinematography, and your insightful reading if the Teavis character as well as the other members if his family reminded me if Ford's film.

Post a Comment