The Cranes are Flying is a Christmas miracle. At least to me.

I guess it was around 2002 that I got my first DVD player. I was excited to build my movie collection and had been hunting out deals and starting to buy lots of Criterion discs off of eBay. I am sure in those early days I focused on movies I knew, I could worry about the other titles later. Then again, I may have had no Criterions at that point, it gets hard to remember after a while. Regardless, it was my first Christmas where getting movies as gifts was a possibility.

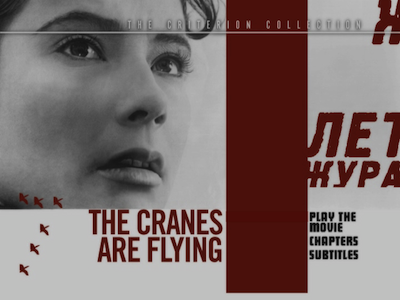

My friend and fellow writer Christopher McQuain and I have an ongoing gift exchange. It's one we never let wane, as we know each other's tastes fairly well and, whenever we can, like to surprise each other with something that maybe the other person hasn't seen, read, or heard. It was that Christmas that Christopher gave me my copy of Mikhail Kalotozov's The Cranes are Flying. I had not heard anything about the film, but he was convinced I would like it.

How right he was. The Cranes are Flying is a 1957 Russian film, a romance swept up in the rush of war. It is a movie that burns with the fever of desire, but that also sinks with the chill of heartbreak. It is both beautifully written and beautiful to look at. More than once I have been asked to compile a list of my essential Criterions, the top 5 or however many everyone should know. Two or three of those choices regularly change, but The Cranes are Flying is one of the mainstays.

The Cranes are Flying opens on a scene of two lovers, Veronica and Boris (Tatiana Samoilova and Alexi Batalov). They have stayed out all night, and morning is fast approaching. Their families know they are seeing each other, but the two of them still act as if it is a secret. Perhaps it is more exciting that way? He calls her Squirrel, and she plays coy. It will be several days before they can see each other again, even though he aches to be with her sooner. Why should it be so urgent? They are young, and they have all the time in the world.

Except they don't. Russia enters World War II, and everything changes. Boris works day and night at the factory, and he has to miss their next date. His cousin Mark (Alexander Shvorin) goes to see Veronica instead. He is a pianist, and he wants to dedicate his music to the dark-haired beauty; she is skeeved out by him and dismisses him.

Boris, of course, ends up joining the army. He could have probably gotten an exemption from the draft, but he volunteered instead. He is called up the day before Veronica's birthday. He leaves behind a stuffed squirrel for her, an object that will take on great importance later, if for no other reason that there is a love letter hidden in its acorn basket. Boris' departure is a tragic scene. Veronica is late and misses him at the apartment, and then she can't find him at the train station, there are too many people and a fence between her and the parade of recruits. Kalatozov creates a terribly sad image here. Veronica has brought her lover a care package full of crackers and cookies and she tosses it toward the departing men in hopes of getting it to its intended, only for the package to break apart. All those treats of nourishment and love are scattered underfoot.

The rest of the movie follows both the war at home and the front lines where Boris is stationed. Bad luck rules on both sides. Veronica loses her parents and is taken in by Boris' family, since they believe he will return and marry her. Instead, during an air raid, Mark takes advantage and presses Veronica into being his own. Kalatozov encapsulates all the violence of war in this one expressionistic scene. Bombs have broken the apartment window, and the only lights are the flashes of fire and explosion. Mark acts like a man possessed, and in some ways, the way director of photography Sergei Urusevsky lights the scene reminds one of a horror movie; in other ways, it's a wartime noir. Flickering lights, bending shadows, and the wide-eyed frenzy of a rapist. Before all this happened, Veronica had declared that she was afraid of nothing; by the end, man's capacity for violence has taken advantage of her every confidence.

This harrowing sequence is one of many virtuouso scenes in The Cranes are Flying. Anyone who has seen Kalatozov's better-known 1964 film I Am Cuba [review] knows that he is a gifted and daring visual storyteller. He is no less ambitious here; in fact, you can see him cutting several cinematic teeth. The director has an elegant sense of composition. Some of his close-ups of Tatiana Samoilova recall Dreyer's tight framing of Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc, whereas in other scenes, the way he and Urusevsky pull the camera back or take it up high so that the characters are rendered small and eclipsed by the background is reminiscent of Welles, particularly the imposing landscapes of The Trial

Perhaps more striking is Kalatozov's sense of movement. Veronica running through the burning ruins of Moscow to her shelled apartment building, darting past rubble and flames, is just as impressive as Kirk Douglas rushing across Kubrick's No Man's Land in Paths of Glory [review]. He caps this frightened dash with another symbolically effective single image: all that is left of Veronica's fourth-floor apartment is the wall clock. It stands tall over the city, its pendulum still swinging. What was that about having nothing but time?

The Cranes are Flying is significant for Urusevsky's pioneering use of handheld cameras. It is particularly noticeable midway through the film, when the family has moved out of Moscow and live in cramped tenements while Boris' father (Vasily Merkuryev) and sister (Svetlana Kharitonova) run the Army hospital. (In a progressive turn, though the father outranks his daughter, he is a general practitioner and she a surgeon.) Veronica works there, as well: she's a volunteer. Things get particularly raw for her when one of the wounded has a fit because he found out his girlfriend married someone else while he was away. Feeling the collective condemnation of all the other soldiers who have their friend's back, Veronica runs from the hospital. The camera alternates between her point of view, running behind and biting at her ankles, and a vantage point just under her chin, looking up at her panicked face. The editing grows choppy, the shutter speed increases, and the race through the village looks like something out of a contemporary action flick. The whole thing ends in a dizzying crash on a bridge, with Veronica saving a child from an oncoming truck. It's like the Odessa Steps sequence from Battleship Potemkin

The child Veronica saves turns out to be named Boris, and he has been separated from his family. The woman sees the obvious coincidence here, and though she doesn't say it, it's like this Boris is a second chance with her Boris, who at this point is missing and possibly dead. Doubles play a subtle importance in Viktor Rozov's script for The Cranes are Flying. There are two air raids that have dire consequences for Veronica. There are the two men, both of them artists--Boris, we are told, draws, while Mark is a musician. Another undisciplined musician proves as dangerous for Boris on the battlefield as Mark does back home. There is also the unseen other girlfriend who could not outlast the battle.

For his part, Kalatozov also creates visual rhymes in the movie. The most obvious, of course, are the V-formation cranes that start and end the movie and give it its title. Also, there is clock tower that we see in the opening credits, and later it is matched by the clock left standing at Veronica's. (And though not a rhyme, notice too how the spiky metal barricades increase with each passing scene, until they finally almost completely box in Mark and Veronica.) More significantly, though, are the two scenes at the train station, first Veronica rushing to try to say good-bye to Boris and then, after the war is over, her hoping to find him amongst the returning troops. In both, she runs along a fence, pushing her way through the crowd, carrying a package, hopeful that she will meet her man. Each ends differently, of course, though you'll hopefully be surprised where Kalatozov manages his emotional upswell.

Tatiana Samoilova is an intriguing actress. As far as I can tell, I haven't seen her in anything else, though I'd be curious to get my hands on Kalatozov's next film, The Unmailed Letter, or the 1967 production of Anna Karenina

I won't go any further into how that happens or even what happens. Though The Cranes are Flying is a romantic melodrama, and thus some of the genre trappings will probably be a little predictable to seasoned viewers, there is still something to be said for the way genre pays off when it's done this well. I certainly found it a surprising cinematic experience at Christmastime eight years ago, and it still has the capacity to bring back that same old feeling. There's no time like the first time, sure, but as with so many things, the second and even third time, what with the nostalgia combined with the things you missed before, manage to only make everything better.

No comments:

Post a Comment