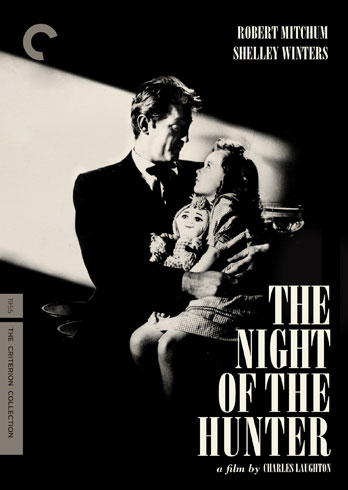

A few weeks ago, while I was waiting for my copy of The Night of the Hunter to ship from Barnes & Noble, my friend Scott Morse watched his. Scott is a comic book artist, as well as a staff member at Pixar. Amongst other things, he designed the end titles for Ratatouille [review] and is one of the main design guys on Cars 2. (Also, these Criterion-themed posters and a comic book about Kurosawa.) Needless to say, Scott has his bonafides when it comes to animation. Thus, when he posted the following to his Twitter, I listened:

NIGHT OF THE HUNTER is a pretty spot-on reverse "princess" story. Studios, take note of the clarity. Drink down the Love and Hate.

THE NIGHT OF THE HUNTER is seriously cut from the same cloth as every Disney flick of the 50's. Iconic, clear, and elegantly shocking.

This is a fascinating theory, and one that absolutely bears out when you watch the movie. Charles Laughton's 1955 tale of menace is a contemporary fairy tale, staged like a children's play, shot like a film noir. From start to finish, it's a unique and daring film. James Agee's script flirts with innuendo, is suspicious of religion, and makes comedic hay of small-town mores. Laughton's direction is both arch and playful, employing film convention to create the safe and familiar, and then undercutting the same technique by deflating the comfortable air right out of its tires.

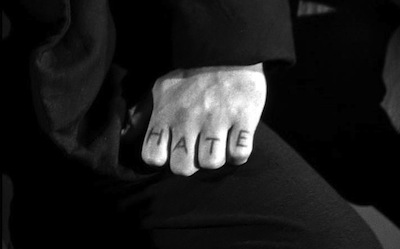

Robert Mitchum stars in the film. Preacher Harry Powell is one of his best-known roles. Though beloved by most of his fans as a hero with a hard jaw, he was a rebellious personality both on and off the screen. A few times in his career, the actor played a villain, revealing one hell of a mean streak. Harry Powell may wear a preacher's suit and hat, but this man has a twisted relationship with God. By his own admission, his version of Christianity is one he and the Supreme Being hammered out together. It's one easily explained, though. He wears his most prominent object lessons on his knuckles. On his left hand, he has tattooed the word HATE, one letter on each finger; on his right, LOVE. A man's hands are meant to work in tandem, but tangle the fingers together, and you'll find two objects at odds with one another. Every living soul is in a constant struggle between hate and love, between doing what is right and giving in to temptation.*

Every living soul except for Harry Powell, that is. Harry is a killer, though the extent of his crimes are just mysterious whispers at the start of The Night of the Hunter. He is pinched watching a burlesque show, but not for the phallic switchblade poking through his suit pocket, nor for the body we saw in an unspecified barn, but because he stole a car. He is sentenced to a month in the hoosegow, where his bunkmate is Ben Harper (Peter Graves). We met Harper when he got arrested. The Night of the Hunter is set in the Great Depression, and Harper killed two men and stole $10,000. Before he got nabbed, he gave the money to his young son John (Billy Chapin) and his even younger sister Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce) and made both of them swear not to tell where he stashed the cash. Ben Harper even goes to the gallows with the secret. The stolen bills are his children's future.

When Powell gets out of jail, he heads to the Harper homestead. There, he seduces Ben's widow (Shelley Winters), and once he is John and Pearl's stepdad, sets about trying to get them to give up the dough. When the woman gets wind of what Powell really married her for--apparently his rejection of her sex and subjugating her to his "religion" was not enough--the preacher murders her and dumps her body. It's a grizzly scene, but filmed to appear dreamy, almost idyllic. The widow Harper is dumped in the river in her Model-T Ford. The currents push her hair along with the underwater weeds, like the mythical Lady of the Lake, though her warning is darker than even that of legend.

With no one to protect them, John and Pearl go on the run. They take their father's rundown boat and set off down the Mississippi. Here, Laughton opens the door to the secret world of children. Most fiction for young readers has a quality of emphasizing the separateness of childhood. When you are small, the bigger world pays you no attention, and thus you can retreat into imagination. Disney films usually have a sense of this, too, though often, instead of kids, it's the parallel world of animals. Think about the cartoons where animals talk, and none of the humans can hear them. So it often seems to be when you are a child: you can talk, but the adults don't concern themselves with what you're saying.**

Tellingly, once the children are in the wilderness, human life fades away, and Laughton designs multiple shots that show the animal population that lives along the water. Spiders, rabbits, turtles, owls--the fugitive orphans and these woodland creatures exist in the same space, and the tiny humans pass unmolested. The animals don't shrink from them, either. This is the realm of fable. They are "other."

This is the most obvious element where the movie matches up to Morse's Disney theory, but there are many more touches throughout The Night of the Hunter that also work to remind us of classic animation. The children's journey is punctuated by songs, mostly schoolground tunes or religious hymns, but that serve to emphasize the emotional tenor of the scenes Laughton uses them in. The trek the kids go on is ostensibly a search for a home, having lost their own and, in a way, having had their identities erased. It's somewhere between Pinocchio

Eventually, John and Pearl wash up on the riverbank near the home of a mother hen figure. Miz Cooper is played by legendary film actress Lillian Gish. She takes in strays and puts them to work in her garden, providing the structure and basic morals they otherwise lack. She is a kindly stepmother, not the wicked kind, and she even serves as a sort of narrative chorus. Cleverly, Agee and Laughton have one of her adopted girls make fun of how she talks to herself all the time, setting us up for the moral Miz Cooper will lay out at the end of the picture. She is both hard and soft, tough on her kids but caring. In contrast to Powell, her behavior is anything but erratic: this is someone the kids can count on. Her home is tidy and traditional; the town nearby is chaotic, lit with neon, full of temptation. Again, it brings to mind Pinocchio and the carnal delights that lead him from Gepetto. The lure of all this sin will call Miz Cooper's oldest charge, Ruby (Gloria Castilo), and Powell will trick her into revealing too much.

Gish is marvelous as the staunch caretaker. She and most of the older character actors really shine under Laughton's direction. Evelyn Garden is particularly good as the annoying busybody Icey Spoon (and she looks exactly like Madam Mim from The Sword in the Stone [review]. I have to admit, though, the child actors aren't that great. Five-year-old Sally Jane Bruce is extremely stiff, looking like she has barely enough attention span to remember what she is supposed to do. Ten-year-old Billy Chapin is quite a bit better, but his performance is actually hurt by Laughton's direction. He regularly isolates the boy for reaction shots, and the way he cuts the scenes doesn't quite connect the boy's expressions to what he is reacting to.

I know this could get me lynched, but I found Laughton's direction to be quite clumsy at other times, too. Some shots are too rigid, and the editing disjointed. Look at, for instance, Powell chasing the children up the cellar stairs. Mitchum appears to be parodying a horror movie ghoul, and it has the appropriate effect, being at once silly and menacing. Yet Laughton and editor Robert Golden don't give the moment its due. They shove a single side shot of this attack into the action, and it doesn't quite fit. For as short as the shot is, it's almost like they started it too early and cut it too soon, you can practically see the marks on either side of Mitchum's lunge. Likewise, for as lovely as those riverbank images of the forest animals can be, they always look like they've been arranged, they aren't natural. Obviously, there are shots throughout the movie that are meant to look like something out of a storybook (observe, for instance, the hangman's children asleep in his shack), and Laughton has done a good job composing them--but it's too good. The illusion bursts.

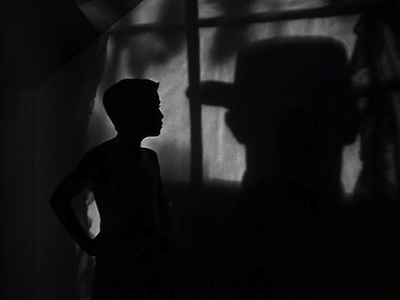

That said, when Laughton and cinematographer Stanley Cortez (who also worked with Orson Welles on The Magnificent Ambersons) are on target, they really are dead center of the bull's-eye. Laughton's use of silhouette and shadow is unmatched in its visual power. He can use light and dark to create both a sense of calm and of terror, and often in the same scene. When the children bed down in a barn, their appearing as shapes against a night sky is serene and lovely; when they awake to hear the approaching Powell singing his signature (and ironic) hymn, the vast horizon suddenly becomes unbearably huge and oppressive. The smaller silhouette in the distance is a threat, and though far away, the distance emphasizes the killer clergy's inescapable presence.

Smartly, as The Night of the Hunter winds down, so too does Laughton dial back the style. His approach has a more old-fashioned, family movie vibe in the last couple of scenes, including the amusing image of Miz Cooper leading her brood through the back alleys like a mother duck and her chicks. In these kinds of stories, the final chapter is when some kind of normalcy is restored, and the traditional Christmas scene Laughton and Agee have concocted is meant to be familiar and homey. No divisive shadows, no extreme angles or compositions, mostly just straight-on shots of Miz Cooper stirring her stew pot, musing on the plight of the wee ones as they move all around her. It's a reassuring finale, restoring the natural order, including letting us know that it's not God or His son that's gone all wrong, but the misguided people of the world that have twisted their positive message. Too much of the left hand, it would seem, and not enough of the right one.

Criterion's two-disc release of The Night of the Hunter, available on standard DVD and Blu-Ray, is an outstanding package. Put together in cahoots with the UCLA Film and Television Archive, the restored print is superb and the collection of extras is a treasure trove of quality supplements, including a clip of the Peter Grave and Shelley Winters giving a live television performance of a scene that ended up cut from the film.

If you're going to watch any extra, however, you must jump over to the second disc. It is devoted to the two-and-a-half-hour documentary Charles Laughton Directs "The Night of the Hunter." This film, put together by Robert Gitt, is a compilation of outtakes and alternate footage from an unprecedented library of dailies that Laughton kept for himself. Gitt uses the raw material to create a history of the production, as well as an alternate version, working through the story in the same narrative order, giving us a glimpse of how a movie is shaped as it is filmed. Deleted shots and flubs share the screen with experiments and rehearsals, as well as curios like Laughton reading from the Bible, author Davis Grubb's sketches he made for the director to show him how he saw his novel portrayed (these also get their own feature on disc 1), and even a scene with the original Uncle Birdie. Emmett Lynn was originally meant to play the old drunk, but Laughton thought his performance was too mannered and cliché. He recast the role with James Gleason--and rightly so judging by what we see here. Gleason nails it.

* Spike Lee would, of course, update this symbolism in Do The Right Thing (another Criterion release), giving Radio Raheem gold rings spelling out each word and likening the struggle of man to something more like a boxing match.

** If you're curious to further explore this secret world of children as portrayed on film, pairing The Night of the Hunter with another Criterion disc, Rene Clement's Forbidden Games, would be a great double-feature.

2 comments:

"as lovely as those riverbank images of the forest animals can be, they always look like they've been arranged, they aren't natural. Obviously, there are shots throughout the movie that are meant to look like something out of a storybook [...] and Laughton has done a good job composing them--but it's too good. The illusion bursts."

Huh? You need to have a long, hard think about the contradictions within this paragraph. You're basically saying "Obviously it's not meant to look natural, but it fails to succeed in this because it looks artificial". Like, what??

I don't feel that's a contradiction at all. In evaluating the technical achievement of a shot or special effect and its aesthetic intention, one must also ask if it works in service to the story. If it takes you out of the movie by calling attention to itself, then it may not be the best choice. That's how I feel about the riverbank scene. Though Laughton wanted something magical, the magic fails when I stop watching the film as a story and start thinking, "Gee, that looks great."

Post a Comment