I love hearing musicians tell stories about performing. It doesn't matter what kind of musician, they don't even have to play a genre I listen to that much, I still like tales from the road or antics in the recording studio. I am not a big blues fan, I don't even think I own a blues record. It's just not a form I've really found my way into. That didn't stop me from enjoying every minute of Louie Bluie, Terry Zwigoff's 1985 portrait of Howard Armstrong. It's the man behind the fiddle that counts here, and the fellow they call Louie Bluie is an entertaining rascal.

Armstrong is a Tennessee-born musician who played fiddle and mandolin in African American "string bands" from the depression onward. By the time Zwigoff turned his camera in Armstrong's direction, he was getting on in years and the music he loved was long past its heyday. Yet, Louie Bluie plays his instrument like every audience is standing room only, and his every anecdote is delivered with humor and flair. He's a talkative subject, most of the film is just Zwigoff hitting "record" and letting the old codger's mouth run. He then shapes the stories into a kind of narrative, visiting locations from Armstrong's past, filming him on tour, and showing how he interacts with his friends and the rest of the band.

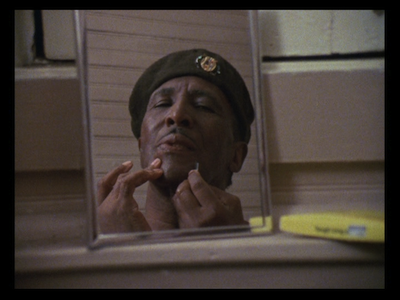

Louie Bluie captures Armstrong at age 75, though you'd never know he was that old. The chatterbox is full of energy, and he plucks at the strings with impressive vigor. He tells jokes about how fast he played when he was young, but it doesn't really seem like Armstrong has slowed at all. Not in any aspect of his life. The first shot of the movie shows him dry shaving with a loose razor blade, and I can't think of a more fitting image to illustrate what a tough old goat Louie Bluie is. Driving the point deeper, the audio is Armstrong, in voiceover, telling us how he is always driven to create. If he isn't making music, he is painting; if he's not painting he is writing poems. He refers to himself as a Jekyll and Hyde, with the Hyde presumably being his creative side. If the good doctor ever gets control from the monster, Zwigoff doesn't share it with us--though I'm thinking that's because he never stumbled on any evidence that Jekyll exists at all.

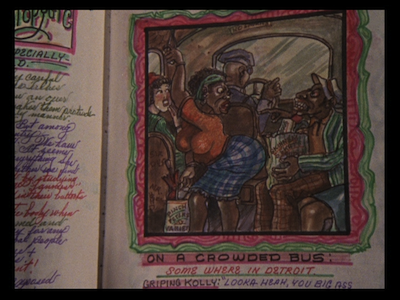

As a filmmaker, Terry Zwigoff's stock-in-trade has always been the uniquely obsessive. Louie Bluie was his first feature, and it points the way to what was to come. When Armstrong pulls his Bible of Pornography out of a locked case and shows it to his friend, it's impossible not to think of Zwigoff's most famous subject, Robert Crumb, and the documentary that bears his name. One of the things that impressed me most about Crumb was how the director was able to push his camera over the artist's shoulder and show his work through his eyes. He does the same here, as Armstrong gleefully explains his ABCs of smut. His use of caricature and appreciation of the more corpulent aspects of the female form is also a lot like Crumb. The famous underground cartoonist actually provides the cover art for this DVD release, and the accompanying booklet features some of Armstrong's own drawings, too.

More important than the sexual peccadilloes, however, is the sense that, like Crumb or Enid in Ghost World

Woody Allen wrote an intro for the movie, which is printed in the DVD booklet. He praises Louie Bluie for preserving the music of times gone by. I'm sorry, though, Woody, I think you miss the point: we should be thanking Terry Zwigoff for preserving this personality, one that sadly left us in 2003. It's not the music, it's the man that makes Louie Bluie a documentary you can watch over and over. It's Howard Armstrong, unfiltered, in his own words. If it was just about the music, all Zwigoff would have needed was a microphone, he could have made a record. Louie Bluie is about one guy, and though he could strike up a fiddle like no one else, it takes a true artist like Zwigoff to see that this isn't the result of practice or that fluke we call talent, but of everything that happened on the way to picking up the bow. The music is made by the performer, not the other way around.

Louie Bluie clip on YouTube

No comments:

Post a Comment